скачать книгу бесплатно

Spring Fire

Vin Packer

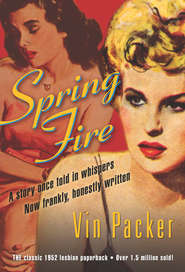

A story once told in whispersNow frankly, honestly writtenThe Classic 1952 lesbian paperback – Over 1.5 million sold!Her silky black hair. Her low-cut gown. Her sparkling sorority pin. It’s autumn rush in the Tri Epsilon house, and the new pledge, Susan Mitchell – “Mitch” to her friends – trembles as the fastest girl on campus, the lovely Leda Taylor, crosses the room toward her for a dance. Will Leda corrupt Mitch? Or will the strong and silent Mitch draw the queen of Tri Ep into the forbidden world of Lesbian Love?Spring Fire was the first lesbian paperback novel and sold an amazing 1.5 million copies when it first appeared in 1952. It launched an entire genre of lesbian novels, as well as the writing career of Vin Packer, one of the pseudonyms of prolific author Marijane Meaker, whose acclaimed memoir, Highsmith: A Romance of the 1950s, told the story of her own forbidden love. Now available after forty years out of print, Spring Fire is both a vital part of lesbian history and a steamy page-turner.Includes a new introduction by the author

Spring Fire

Vin Packer

www.spice-books.co.uk (http://www.spice-books.co.uk)

Table of Contents

Cover (#u7ca14dd2-52cf-5bc7-be34-8efdb6a0d4fd)

Title Page (#u504ad71d-f339-53a5-bc6b-8eace0062934)

Introduction (#ua0a4b74f-8b22-54e4-af9d-1f05a1823cac)

Chapter One (#u2ad2bd31-86c8-529a-ba6f-901b88695c87)

Chapter Two (#ud9f88149-0cad-5216-b4e6-d7568298c1b7)

Chapter Three (#uee65abcf-64b4-521f-973c-152866be3fda)

Chapter Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Endpages (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_83c51a49-635f-5190-8dbc-381c49b8e08b)by Vin Packer

I was having drinks in a little bar inside the Algonquin Hotel, with an editor named Dick Carroll, when he asked me, “What kind of story is a young girl like you burning to tell?” He was grinning at me, as though any answer to that question would be frivolous and lightweight. After all, I had gone to work for him straight out of college, only months before. I roomed with three sorority sisters. I was just finding my way around New York City.

I said, “I’d like to write about boarding school. I went because I had heard homosexuality ran rampant in places like that. I wanted to find out if my suspicions were right, that I was one of those. Sure enough, I was rewarded with first love.”

“A little love story with a twist, hmmm?”

“Yes, but not a happy ending. I didn’t think I was strong enough to go through all the secrecy and disapproval. Her mother found one of my letters to her and called my parents threatening to call the police if I ever contacted her daughter again.”

“What happened next?” Dick asked.

“My parents told me, and I told myself, that it was just a silly schoolgirl thing. All I needed to do was put myself in a male/female environment. So I chose the University of Missouri, co-ed, and with a fine journalism school, since I wanted to be a writer.”

“Were you cured?” Dick asked.

“I had a wonderful time. I pledged a sorority. I fell in love with a Hungarian who’d escaped the Holocaust. I began to write story after story. That was when I learned there wasn’t a cure. My Hungarian wasn’t enough, nor were my friends, and my stories were missing something, too. So that’s what I’d like to write about, if there were a way.”

Dick told me maybe there was a way.

He was the new editor of a line of paperback originals called Gold Medal Books, brought out by Fawcett Publications. The idea that good books could appear in paper without having to be in hardcover first was new. I was one of Dick’s secretaries, who didn’t know how to take shorthand, so I was assigned to read books thought to have potential, selected from the slush pile. A would-be writer, I very often finished reading a new manuscript thinking: I could do that.

“You might have a good story there,” Dick said, “but you’d have to do two things. The girls would have to be in college, not boarding school. And, you cannot make homosexuality attractive. No happy ending.”

“Well, my story didn’t have a happy ending, anyway.”

“But your main character can’t decide she’s not strong enough to live that life,” Dick said. “She has to reject it knowing that it’s wrong. You see, our books go through the mails. They have to pass inspection. If one book is considered censurable, the whole shipment is sent back to the publisher. If your book appears to proselytize for homosexuality, all the books sent with it to distributors are returned. You have to understand that. I don’t care about anybody’s sexual preference. But I do care about making this new line successful.”

“In other words, my heroine has to decide she’s really not queer.”

“That’s it. And the one she’s involved with is sick or crazy.”

He told me that if I wrote an outline and submitted it with one chapter, he would advance me $1000.

A month later, Sorority Girl was on the Gold Medal Schedule. Since they paid a penny a copy on print order, and usually printed 400,000 copies, I would receive $3000 more when I was finished.

After Dick read the final manuscript, he said we would have to change the title.

“It has no particular sales pull,” he said.

“I don’t want it to have an unhappy title like The Well of Loneliness,” I said.

“Neither do I,” said Dick. “I want to call it Spring Fire.”

“What? What does that even mean?”

“It means there’s a big seller by James Michener called The Fires of Spring, and we might pick up a few readers who confuse the titles.”

I just stared back at him in disbelief.

“Look,” he said, “I’m taking a big chance here because this is the story you told me you wanted to write. Fawcett Publications is taking a chance, too. Do you really think there’s much of an audience out there for this? It’s set in a sorority, for Pete’s sake! We have to jazz up the title and wrap it in a sexy cover. We have to! This is a business.”

So it was that the book was called Spring Fire, and at the end one young woman goes mad, while the other realizes she had never really loved her in the first place. While that may have satisfied the post office inspectors, the homosexual audience would not have believed that for a minute. But they also wouldn’t care that much, because more important was the fact there was a new book about us. Suddenly, we were on the newsstands and in the magazine stores, right up front on the racks.

Lesbians and homosexuals, in those days, had no sense of entitlement. The majority of us were closeted. A lot of us went to big cities so we could find others, mostly in bars catering to us. I was still dating men. My sorority sisters knew nothing about my homosexual love affair in boarding school. They had no idea that more and more when I went on dates, I was asking my “boyfriends” to find bars where lesbians went, claiming that I wanted to do an article about such women. Although the word gay was becoming popular among us, it had not yet been mainstreamed. There were no magazines or newspapers about us, no clubs for us to belong to. Books written about us were very few with small print orders, and not reviewed in major publications. We were never mentioned in radio dramas or soap operas and needless to say as television got started, we were not in the scripts. The church and synagogues called us sinners, as they still do, and the law called us criminals. We had no legitimacy.

This is not to say the “twilight path” was filled with broken glass.

We had good times despite our oppressors, the rules against us, and our invisibility. But it would be many years before enough of us gained the self-respect that made us fight against the labels “abnormal” and “perverse,” and begin to realize our numbers, our strength, and our potential politically.

In 1952 when Spring Fire was published it sold 1,463,917 copies in its first printing, more than The Postman Always Rings Twice by James Cain and more than My Cousin Rachel by Daphne du Maurier sold in that same year.

Fan mail arrived by the cartons, a second printing, then a third, were ordered immediately. I was invited upstairs to the publishers’ penthouse where Roger Fawcett would shake my hand and show me his new toy, a naked male statue with soda water dispensed through the gold penis.

Spring Fire kept me for many years, although the Vin Packer pseudonym would henceforth be used for suspense books.

I had randomly chosen that name after having lunch with a man named Vincent and a woman whose last name was Packer.

I went on to write suspense solely because I was told that major mystery critics always reviewed paperback books, too.

There were two more Packer books, of twenty-two, dealing with homosexuality, but both were true crimes fictionalized. Whisper His Sin (my title had been One to Destroy) was the Fraden/Wepman cyanide cocktail murder, a matricide in Manhattan. Then The Evil Friendship (my title had been Why Not Mother?) was the Parker/Hulme New Zealand matricide, called to my attention by the New York Times mystery critic, Anthony Boucher.

I created another new identity, Ann Aldrich, writing for Gold Medal a journalistic series reporting on lesbian life in New York City. There were five books in all, their titles reflecting the changing mores. The first title was We Walk Alone, and the last one was Take a Lesbian to Lunch.

These were all non-fiction books, which also realized many repeat printings.

If anything, Spring Fire (and the Aldrich books) alerted the publishing world to the fact there was a very large audience for books about lesbians. Of course, some of the readers were men, hoping for a pornographic buzz, but the fan mail came from women all over the United States.

On the cover were two females who looked a lot like hookers, sitting in their slips on a bed. Lesbian readers were able to look past the cover: to find themselves between the pages. We always found ourselves. Some incredible word-of-mouth, grapevine, whatever you want to call it, alerted us to the books, just as we found our bars, and just as we heard the gossip about movie stars and sports stars, actors, poets, and public figures who were like us, and from whom we could borrow glory.

For years I have been reluctant to have Spring Fire returned to print.

My first book, it is a very young book. There is a lot that embarrasses me about the writing. As soon as I became politically conscious, the ending, of course, embarrassed me.

But now that I am older, I am less hard on the young writer whose mother cried out, upon receipt of a copy, “Have you no shame?” And now when I explain to the younger generation what lesbian life was like in the ’50s, I make no apologies. We did what we had to do, informed by the times. Shameless, persevering, we began recording our history … and this is part of it.

Vin Packer

Chapter One (#ulink_a535fc5a-af69-57c6-b940-d7244389996d)

IT WAS TWO-THIRTY IN THE AFTERNOON, late September, with the sun beating down the way it does then in the Midwest, and the dust in the streets. The girl, Susan Mitchell, was wearing a green linen suit that clung on her large body heavily, a round white straw hat from which short pieces of blonde hair hung limply, and brown and white shoes with low heels that made her long feet look longer. She was not pretty. She was not lovely and dainty and pretty, but there was a comeliness about her that suggested some inbred strength and grace. It was in her face. It was in the color of her eyes—deep blue like the ocean way out there, but quiet and still. It was in the structure of her cheekbones, high and firm coming down to pull her chin up. She walked that way, too. She walked easy and sure. She was following College Avenue down to where the main gate was, and the road that led through the gate to the campus of Cranston University. All around her there were signs in the windows of bookstores and drugstores and dress shops and bars and the signs said: “WELCOME BACK C.U.”

The gate was open and the wide slate walks surrounding the immense green lawn were dotted with boys and girls, walking together in groups, sitting alone on benches, standing thoughtfully in doorways, and waiting wearily in long registration lines. Susan Mitchell had registered two weeks ago.

“You’ll have enough to think about during rush week,” her father had promised, “without worrying about getting yourself enrolled. We’ll do it early. Then you can concentrate on impressing those sorority gals. Don’t be nervous either. Remember, your father still loves you, no matter what.”

And so it was there again—his fear for her. His fear that she was not good enough. Because he had not been. He had worked hard, and not gone to college, and not had luxuries, and not learned not to say “ain’t,” and not anything. Until the war and the men came that day and looked at the factory and talked with him and signed papers and he was rich then. And then he was afraid.

He had driven her from Kansas City to register, and when she had finished, he had asked someone how to get to “Greek Town,” and with him she had first seen it.

Greek Town was the home of the sororities and fraternities and it was magic over there, close to the stadium, within walking distance of the campus, but not huddled up in narrow streets the way the dorms and boardinghouses were. It was magic, with street after street of grand houses—brick, stucco, stone, and fresh white wooden houses. Each one had a gold plaque with shining Greek letters, and nearly all of them had spacious yards, winding driveways, and huge white columns that stood impressively, symbols of magnificence. Then she too had felt a thin shiver of fear.

Tomorrow she would go to the sorority houses to be judged; but now as she walked on the campus she forgot about that momentarily, and smelled the grass that had been cut and watered, and it was good. The ivy, crawling up along the walls of the building, was massive and cooling, and the big trees made shade along the path. She sat for a while on the rock bench there where the breeze came along, and it was peaceful.

A group of laughing girls passed, arms entwined, faces glowing with excitement.

“… anyway,” one of them was saying, “it turned out he was from St. Louis—Webster, in fact—and he knew loads of kids I knew.”

“My God!” another shrieked. “Didn’t you tell him I was from Webster?”

Later Susan Mitchell walked back toward the gate and the street leading to the hotel where she was staying. A convertible whizzed by and kicked up clouds of the dust that settled near the curb, and at the corner when it turned, the tires squealed nervously. In the doorway of a restaurant, a tall boy stood holding hands with a small, brown-eyed girl whose hair was flaxen. “God,” he said, “all summer I had you on my mind, Annie. No bull, I thought about you all summer.”

When Susan Mitchell reached the lobby of the hotel, the low leather couches and chairs were filled with girls, and several rows of luggage were lined up near the desk. She asked for her key, wary of the arrogant, crooked-nosed clerk who always yelled, as he did now. “Speak up, girlie,” he said. “I ain’t deaf and I can’t read lips.”

“Susan Mitchell,” the girl said louder. “Four-o-one.”

He handed her the metal key with the wooden tab attached and she hurried off to the waiting elevator.

“Good God,” the uniformed pimple-faced boy said when she stepped into the small box. “You girls! Up and down all the damn day long! I never seen the likes of this bunch. The sororities are welcome to you!”

“The next name, girls,” Mother Nesselbush said, “is Susan Mitchell.”

At her feet, sitting on the wide tan rug, the members of Tri Epsilon polished their nails, knitted, rubbed cold cream into their skin, and rolled their hair up on rags and iron curlers and bobby pins. Mother Nesselbush thumbed through the papers on the card table in front of her. She was a fat woman with a nervous twitch in her jowls and short, squat legs. Twenty years ago she had been a slim coed with long golden hair, a gay young face, and a heart-shaped Tri Epsilon pin attached to her budding bosom. Five years ago, when J. Edman Nesselbush fell dead, she returned to the Cranston campus and took over the duties of the housemother at Epsilon Epsilon Epsilon. Now she was a wide dowager with wiry gray hair and a worn, wrinkled face. In place of the pin now, there was a gravy stain from the noon meal slopped onto her broad, lace-covered chest.

“Now,” Mother Nessy began, “a little about this girl.” The information on Susan Mitchell had been obtained by Edith Wellard Boynton, ’22. Mrs. Boynton relished the task. She was a superior sleuth, and she would often come from an assignment with copious notes on such intimate details as the estimated income of the candidate’s father; the color of the guest towels in the candidate’s bathroom and the condition of said bathroom; the morals of the candidate, the candidate’s mother, father, brother, and sister; and ever important, the social prestige of the candidate’s family in the community. Then she would type up her notes and send them special delivery.

Susan Mitchell’s report read:

An absolute must for Tri Epsilon. The Mitchell girl is 17. Her father is a widower and a millionaire. There are no other children. The Mitchell girl owns a brilliant red convertible, Buick, latest model. Edward Mitchell belongs to Rotary, Seedmore Country Club, Seedmore Business Club, and Seedmore P.T.A. Susan has been educated in the best private schools. She is not beautiful, but she is wholesome and a fine athlete. Every room in the Mitchell home has wall-to-wall carpeting. There are four bathrooms. No mortgages. Edward Mitchell’s reputation is above reproach. They are definitely nouveaux riches, but their social prestige in Seedmore is tiptop. Susan has a fabulous wardrobe. Kansas City Alum Association puts a stamp of approval on this girl, and a definite “Yes! Yes! Yes!”

When Mother Nesselbush finished reading what Mrs. Boynton had written, there was a sudden minute of silence. Then Leda Taylor spoke up.

“What if she’s a muscle-bound amazon? Do we have to pledge the girl just because her father is worth a mint?”

Leda Taylor did not have a father. Not a father she knew. Jan, her mother, had raised Leda single-handed, with the help of her job as a dress designer and a good stiff Martini. It had not been easy for Jan. As Leda grew older, Jan’s age became more obvious to men and she always had to say, “I had my baby when I was a baby, really—I was just a baby when little Leda was born.” Little Leda grew fast and fully and richly. She had long black hair that shone like new coal, round green eyes, a stubborn tilt to her chin, proud pear-shaped breasts that pointed through her size 36 sweater, and long, graceful legs. Jan had taught her never to say “Mother.” Leda said “Jan.” She said, “Oh, God, Jan is getting higher than a kite!” when they were all out on parties like that—Leda and the men who clambered after Jan and Jan with her glass raised and her voice growing shrill. Leda said, “Jan, for the love of God, let me pick my own men. I don’t want your castoffs,” when she was home in the summer and Jan was always entertaining. Then in the fall, Leda said, “Take it easy, Jan. Stay sober,” and the train moved away, toward Cranston and college and the house.

Mother Nesselbush sighed and answered Leda. “This is a pretty strong note, dear. You know our alums never make their requests quite so adamant.”

Kitten Clark tapped her nails angrily on the top of the glass coffee table. She was the official social chairman for the sorority, the girl who was responsible for seeing that Tri Eps dated fraternity men. Her motto was pasted up over the mirror in the soft jade-green room where she and Marybell Van Casey lived: “If he’s got a pin—he’s in!”

Underneath these words, a penciled addition to the rule read blithely: “Like Flynn!”

“Nessy,” Kitten said, “so far on our list we have four goon girls. Legacies. We have to take legacies, but we don’t have to take Susan Mitchell! What did the K.C. alums ever do for us?”

Viola Nesselbush straightened herself, tugged harshly at her corset, and leaned forward intimately. She whispered in a rasping tone, one finger held forward significantly. “Now listen, girls. Remember that new set of silverware you all want for the house? The one with the Tri Epsilon crest on it? Well, girls, if we pledge this little girl, I think the K.C. alums will see to it that you get that silverware. In fact, girls,” she added coyly, “I’ll personally guarantee it.”

A spontaneous round of applause rose from the gathering, and the faces of the Tri Eps grinned approval. “She may be halfway attractive,” Marybell Van Casey offered. “After all, just because she’s a sweat-socks is no sign she’s utterly repulsive.”

Casey’s voice was tinged with defiance. She was a major in physical education, and all of her classes, with the exception of English and vertebrate zo, took place in the arid surroundings of the gymnasium. Her build was heavy and muscular, but her face was pleasant and attractive and she was pinned to a Delta Pi who played baseball.

The president of Tri Epsilon sorority rose gracefully and stood beside the piano facing the group. She wore a crisp pair of white shorts, a black halter, and a black velvet ribbon in her hair. Her name was Marsha Holmes, and there was a mild, poised quality about her that commanded respect and admiration from her sorority sisters. Whenever Marsha spoke, her gray eyes watched the individual faces of her audience carefully, and her low husky voice made her words sound wistful and honest. Marsha had learned much about people from her father, the Reverend Thomas Holmes, and the serenity she wore so easily had been practiced long years at church functions.

“I think everyone agrees,” she said calmly, “that Susan Mitchell is excellent Tri Epsilon material. The purpose of a sorority is to help a girl grow, and if Susan needs our help, it will be our privilege to give it to her. Let’s all make a special effort to show Susan that Tri Epsilon is a friendly house—the kind of house that she would be proud to live in.”