Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson – Swanston Edition. Volume 18

Off they set, with two guns and three porters, and Fono and Lloyd and Palema and Talolo himself with best Sunday-go-to-meeting lavalava rolled up under his arm, and a very sore foot; but much he cared – he was smiling from ear to ear, and would have gone to Siumu over red-hot coals. Off they set round the corner of the cook-house, and into the bush beside the chicken-house, and so good-bye to them.

But you should see how Iopu has taken possession! “Never saw a place in such a state!” is written on his face. “In my time,” says he, “we didn’t let things go ragging along like this, and I’m going to show you fellows.” The first thing he did was to apply for a bar of soap, and then he set to work washing everything (that had all been washed last Friday in the regular course). Then he had the grass cut all round the cook-house, and I tell you but he found scraps, and odds and ends, and grew more angry and indignant at each fresh discovery.

“If a white chief came up here and smelt this, how would you feel?” he asked your mother. “It is enough to breed a sickness!”

And I dare say you remember this was just what your mother had often said to himself; and did say the day she went out and cried on the kitchen steps in order to make Talolo ashamed. But Iopu gave it all out as little new discoveries of his own. The last thing was the cows, and I tell you he was solemn about the cows. They were all destroyed, he said, nobody knew how to milk except himself – where he is about right. Then came dinner and a delightful little surprise. Perhaps you remember that long ago I used not to eat mashed potatoes, but had always two or three boiled in a plate. This has not been done for months, because Talolo makes such admirable mashed potatoes that I have caved in. But here came dinner, mashed potatoes for your mother and the Tamaitai, and then boiled potatoes in a plate for me!

And there is the end of the Tale of the return of Iopu, up to date. What more there may be is in the lap of the gods, and, Sir, I am yours considerably,

Uncle Louis.VIIITO AUSTIN STRONGMy Dear Hoskyns, – I am kept away in a cupboard because everybody has the influenza; I never see anybody at all, and never do anything whatever except to put ink on paper up here in my room. So what can I find to write to you? – you, who are going to school, and getting up in the morning to go bathing, and having (it seems to me) rather a fine time of it in general?

You ask if we have seen Arick? Yes, your mother saw him at the head of a gang of boys, and looking fat, and sleek, and well-to-do. I have an idea that he misbehaved here because he was homesick for the other Black Boys, and didn’t know how else to get back to them. Well, he has got them now, and I hope he likes it better than I should.

I read the other day something that I thought would interest so great a sea-bather as yourself. You know that the fishes that we see, and catch, go only a certain way down into the sea. Below a certain depth there is no life at all. The water is as empty as the air is above a certain height. Even the shells of dead fishes that come down there are crushed into nothing by the huge weight of the water. Lower still, in the places where the sea is profoundly deep, it appears that life begins again. People fish up in dredging-buckets loose rags and tatters of creatures that hang together all right down there with the great weight holding them in one, but come all to pieces as they are hauled up. Just what they look like, just what they do or feed upon, we shall never find out. Only that we have some flimsy fellow-creatures down in the very bottom of the deep seas, and cannot get them up except in tatters. It must be pretty dark where they live, and there are no plants or weeds, and no fish come down there, or drowned sailors either, from the upper parts, because these are all mashed to pieces by the great weight long before they get so far, or else come to a place where perhaps they float. But I dare say a cannon sometimes comes careering solemnly down, and circling about like a dead leaf or thistle-down; and then the ragged fellows go and play about the cannon and tell themselves all kinds of stories about the fish higher up and their iron houses, and perhaps go inside and sleep, and perhaps dream of it all like their betters.

Of course you know a cannon down there would be quite light. Even in shallow water, where men go down with a diving-dress, they grow so light that they have to hang weights about their necks, and have their boots loaded with twenty pounds of lead – as I know to my sorrow. And with all this, and the helmet, which is heavy enough of itself to any one up here in the thin air, they are carried about like gossamers, and have to take every kind of care not to be upset and stood upon their heads. I went down once in the dress, and speak from experience. But if we could get down for a moment near where the fishes are, we should be in a tight place. Suppose the water not to crush us (which it would), we should pitch about in every kind of direction; every step we took would carry us as far as if we had seven-league boots; and we should keep flying head over heels, and top over bottom, like the liveliest clowns in the world.

Well, sir, here is a great deal of words put down upon a piece of paper, and if you think that makes a letter, why, very well! And if you don’t, I can’t help it. For I have nothing under heaven to tell you.

So, with kindest wishes to yourself, and Louie, and Aunt Nellie, believe me, your affectionate

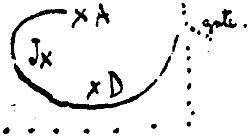

Uncle Louis.Now here is something more worth telling you. This morning at six o’clock I saw all the horses together in the front paddock, and in a terrible ado about something. Presently I saw a man with two buckets on the march, and knew where the trouble was – the cow! The whole lot cleared to the gate but two – Donald, the big white horse, and my Jack. They stood solitary, one here, one there. I began to get interested, for I thought Jack was off his feed. In came the man with the bucket and all the ruck of curious horses at his tail. Right round he went to where Donald stood (D) and poured out a feed, and the majestic

Glory be to the name of Donald and to the name of Jack, for they had found out where the foods were poured, and each took his station and waited there, Donald at the first of the course for his, Jack at the second station, while all the impotent fools ran round and round after the man with his buckets!

R. L. S.IXTO AUSTIN STRONGVailima.My Dear Austin, – Now when the overseer is away22 I think it my duty to report to him anything serious that goes on on the plantation.

Early the other afternoon we heard that Sina’s foot was very bad, and soon after that we could have heard her cries as far away as the front balcony. I think Sina rather enjoys being ill, and makes as much of it as she possibly can; but all the same it was painful to hear the cries; and there is no doubt she was at least very uncomfortable. I went up twice to the little room behind the stable, and found her lying on the floor, with Tali and Faauma and Talolo all holding on different bits of her. I gave her an opiate; but whenever she was about to go to sleep one of these silly people would be shaking her, or talking in her ear, and then she would begin to kick about again and scream.

Palema and Aunt Maggie took horse and went down to Apia after the doctor. Right on their heels off went Mitaele on Musu to fetch Tauilo, Talolo’s mother. So here was all the island in a bustle over Sina’s foot. No doctor came, but he told us what to put on. When I went up at night to the little room, I found Tauilo there, and the whole plantation boxed into the place like little birds in a nest. They were sitting on the bed, they were sitting on the table, the floor was full of them, and the place as close as the engine-room of a steamer. In the middle lay Sina, about three parts asleep with opium; two able-bodied work-boys were pulling at her arms, and whenever she closed her eyes calling her by name, and talking in her ear. I really didn’t know what would become of the girl before morning. Whether or not she had been very ill before, this was the way to make her so, and when one of the work-boys woke her up again, I spoke to him very sharply, and told Tauilo she must put a stop to it.

Now I suppose this was what put it into Tauilo’s head to do what she did next. You remember Tauilo, and what a fine, tall, strong, Madame Lafarge sort of person she is? And you know how much afraid the natives are of the evil spirits in the wood, and how they think all sickness comes from them? Up stood Tauilo, and addressed the spirit in Sina’s foot, and scolded it, and the spirit answered and promised to be a good boy and go away. I do not feel so much afraid of the demons after this. It was Faauma told me about it. I was going out into the pantry after soda-water, and found her with a lantern drawing water from the tank. “Bad spirit he go away,” she told me.

“That’s first-rate,” said I. “Do you know what the name of that spirit was? His name was tautala (talking).”

“O, no!” she said; “his name is Tu.”

You might have knocked me down with a straw. “How on earth do you know that?” I asked.

“Heerd him tell Tauilo,” she said.

As soon as I heard that I began to suspect Mrs. Tauilo was a little bit of a ventriloquist; and imitating as well as I could the sort of voice they make, asked her if the bad spirit did not talk like that. Faauma was very much surprised, and told me that was just his voice.

Well, that was a very good business for the evening. The people all went away because the demon was gone away, and the circus was over, and Sina was allowed to sleep. But the trouble came after. There had been an evil spirit in that room and his name was Tu. No one could say when he might come back again; they all voted it was Tu much; and now Talolo and Sina have had to be lodged in the Soldier Room.23 As for the little room by the stable, there it stands empty; it is too small to play soldiers in, and I do not see what we can do with it, except to have a nice brass name-plate engraved in Sydney, or in “Frisco,” and stuck upon the door of it —Mr. Tu.

So you see that ventriloquism has its bad side as well as its good sides; and I don’t know that I want any more ventriloquists on this plantation. We shall have Tu in the cook-house next, and then Tu in Lafaele’s, and Tu in the workman’s cottage; and the end of it all will be that we shall have to take the Tamaitai’s room for the kitchen, and my room for the boys’ sleeping-house, and we shall all have to go out and camp under umbrellas.

Well, where you are there may be schoolmasters, but there is no such thing as Mr. Tu!

Now, it’s all very well that these big people should be frightened out of their wits by an old wife talking with her mouth shut; that is one of the things we happen to know about. All the old women in the world might talk with their mouths shut, and not frighten you or me, but there are plenty of other things that frighten us badly. And if we only knew about them, perhaps we should find them no more worthy to be feared than an old woman talking with her mouth shut. And the names of some of these things are Death, and Pain, and Sorrow.

Uncle Louis.XTO AUSTIN STRONGJan. 27, 1893.Dear General Hoskyns, – I have the honour to report as usual. Your giddy mother having gone planting a flower-garden, I am obliged to write with my own hand, and, of course, nobody will be able to read it. This has been a very mean kind of a month. Aunt Maggie left with the influenza. We have heard of her from Sydney, and she is all right again; but we have inherited her influenza, and it made a poor place of Vailima. We had Talolo, Mitaele, Sosimo, Iopu, Sina, Misifolo, and myself, all sick in bed at the same time; and was not that a pretty dish to set before the king! The big hall of the new house having no furniture, the sick pitched their tents in it, – I mean their mosquito-nets, – like a military camp. The Tamaitai and your mother went about looking after them, and managed to get us something to eat. Henry, the good boy! though he was getting it himself, did housework, and went round at night from one mosquito-net to another, praying with the sick. Sina, too, was as good as gold, and helped us greatly. We shall always like her better. All the time – I do not know how they managed – your mother found the time to come and write for me; and for three days, as I had my old trouble on, and had to play dumb man, I dictated a novel in the deaf-and-dumb alphabet. But now we are all recovered, and getting to feel quite fit. A new paddock has been made; the wires come right up to the top of the hill, pass within twenty yards of the big clump of flowers (if you remember that) and by the end of the pineapple patch. The Tamaitai and your mother and I all sleep in the upper story of the new house; Uncle Lloyd is alone in the workman’s cottage; and there is nobody at all at night in the old house, but ants and cats and mosquitoes. The whole inside of the new house is varnished. It is a beautiful golden-brown by day, and in lamplight all black and sparkle. In the corner of the hall the new safe is built in, and looks as if it had millions of pounds in it; but I do not think there is much more than twenty dollars and a spoon or two; so the man that opens it will have a great deal of trouble for nothing. Our great fear is lest we should forget how to open it; but it will look just as well if we can’t. Poor Misifolo – you remember the thin boy, do you not? – had a desperate attack of influenza; and he was in a great taking. You would not like to be very sick in some savage place in the islands, and have only the savages to doctor you? Well, that was just the way he felt. “It is all very well,” he thought, “to let these childish white people doctor a sore foot or a toothache, but this is serious – I might die of this! For goodness’ sake let me get away into a draughty native house, where I can lie in cold gravel, eat green bananas, and have a real grown-up, tattooed man to raise spirits and say charms over me.” A day or two we kept him quiet, and got him much better. Then he said he must go. He had had his back broken in his own islands, he said; it had come broken again, and he must go away to a native house and have it mended. “Confound your back!” said we; “lie down in your bed.” At last, one day, his fever was quite gone, and he could give his mind to the broken back entirely. He lay in the hall; I was in the room alone; all morning and noon I heard him roaring like a bull calf, so that the floor shook with it. It was plainly humbug; it had the humbugging sound of a bad child crying; and about two of the afternoon we were worn out, and told him he might go. Off he set. He was in some kind of a white wrapping, with a great white turban on his head, as pale as clay, and walked leaning on a stick. But, O, he was a glad boy to get away from these foolish, savage, childish white people, and get his broken back put right by somebody with some sense. He nearly died that night, and little wonder! but he has now got better again, and long may it last! All the others were quite good, trusted us wholly, and stayed to be cured where they were. But then he was quite right, if you look at it from his point of view; for, though we may be very clever, we do not set up to cure broken backs. If a man has his back broken we white people can do nothing at all but bury him. And was he not wise, since that was his complaint, to go to folks who could do more?

Best love to yourself, and Louie, and Aunt Nellie, and apologies for so dull a letter from your respectful and affectionate

Uncle Louis.END OF VOL. XVIII1

In English usually written “taboo”: “tapu” is the correct Tahitian form. – [ED.]

2

The reference is to Maka, the Hawaiian missionary, at Butaritari, in the Gilberts.

3

Elephantiasis.

4

Arorai is in the Gilberts, Funafuti in the Ellice Islands. – Ed.

5

For an account of the writer’s visit to the leper settlement, see Letters, section x.

6

Gin and brandy.

7

In the Gilbert group.

8

Copra: the dried kernel of the cocoa-nut, the chief article of commerce throughout the Pacific Islands.

9

Houses.

10

Suppose.

11

i. e. in building a section of a new road to Mr. Stevenson’s house. The paper referred to is a copy of the Samoa Times, containing a report of the dinner given by Mr. Stevenson at Vailima to inaugurate this new road.

12

The lady to whom the first three of these letters are addressed “used to hear” (writes Mr. Lloyd Osbourne) “so frequently of the ‘boys’ in Vailima, that she wrote and asked Mr. Stevenson for news of them, as it would so much interest her little girls. In the tropics, for some reason or other that it is impossible to understand, servants and work-people are always called ‘boys,’ though the years of Methuselah may have whitened their heads, and great-grandchildren prattle about their knees. Mr. Stevenson was amused to think that his ‘boys,’ who ranged from eighteen years of age to threescore and ten, should be mistaken for little youngsters; but he was touched to hear of the sick children his friend tried so hard to entertain, and gladly wrote a few letters to them. He would have written more but for the fact that his friend left the home, being transferred elsewhere.”

13

Come-a-thousand.

14

The German company, from which we got our black boy Arick, owns and cultivates many thousands of acres in Samoa, and keeps at least a thousand black people to work on its plantations. Two schooners are always busy in bringing fresh batches to Samoa, and in taking home to their own islands the men who have worked out their three years’ term of labour. This traffic in human beings is called the “labour trade,” and is the life’s blood, not only of the great German company, but of all the planters in Fiji, Queensland, New Caledonia, German New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and the New Hebrides. The difference between the labour trade, as it is now carried on under Government supervision, and the slave trade is a great one, but not great enough to please sensitive people. In Samoa the missionaries are not allowed by the company to teach these poor savages religion, or to do anything to civilise them and raise them from their monkey-like ignorance. But in other respects the company is not a bad master, and treats its people pretty well. The system, however, is one that cannot be defended and must sooner or later be suppressed. – [L.O.]

15

When Arick left us and went back to the German company, he had grown so fat and strong and intelligent that they deemed he was made for better things than for cotton-picking or plantation work, and handed him over to their surveyor, who needed a man to help him. I used often to meet him after this, tripping at his master’s heels with the theodolite, or scampering about with tapes and chains like a kitten with a spool of thread. He did not look then as though he were destined to die of a broken heart, though that was his end not so many months afterward. The plantation manager told me that Arick and a New Ireland boy went crazy with home-sickness, and died in the hospital together. – [L.O.]

16

“Bullamacow” is a word that always amuses the visitor to Samoa. When the first pair of cattle was brought to the islands and the natives asked the missionaries what they must call these strange creatures, they were told that the English name was a “bull and a cow.” But the Samoans thought that “a bull and a cow” was the name of each of the animals, and they soon corrupted the English words into “bullamacow,” which has remained the name for beef or cattle ever since. – [L.O.]

17

In the letters that were sent to Austin Strong you will be surprised to see his name change from Austin to Hoskyns, and from Hopkins to Hutchinson. It was the penalty Master Austin had to pay for being the particular and bosom friend of each of the one hundred and eighty bluejackets that made up the crew of the British man-of-war Curaçoa; for, whether it was due to some bitter memories of the Revolutionary war, or to some rankling reminiscences of 1812, that even friendship could not altogether stifle (for Austin was a true American boy), they annoyed him by giving him, each one of them, a separate name. – [L.O.]

18

The big conch-shell that was blown at certain hours every day. – [L.O.]

19

Mrs. R. L. S., as she is called in Samoan, “the lady.” – [L.O.]

20

A visiting party.

21

Talolo was the Vailima cook; Sina, his wife; Tauilo, his mother; Mitaele and Sosimo, his brothers. Lafaele, who was married to Faauma, was a middle-aged Futuna Islander, and had spent many years of his life on a whale-ship, the captain of which had kidnapped him when a boy. Misifolo was one of the “house-maids.” Iopu and Tali, man and wife, had long been in our service, but had left it after they had been married some time; but, according to Samoan ideas, they were none the less members of Tusitala’s family, because, though they were no longer working for him, they still owed him allegiance. “Aunt Maggie” is Mr. Stevenson’s mother; Palema, Mr. Graham Balfour. – [L.O.]

22

While Austin was in Vailima many little duties about the plantation fell to his share, so that he was often called the “overseer”; and small as he was, he sometimes took charge of a couple of big men, and went into town with the pack-horses. It was not all play, either, for he had to see that the barrels and boxes did not chafe the horses’ backs, and that they were not allowed to come home too fast up the steep road. – [L.O.]

23

A room set apart to serve as the theatre for an elaborate war-game, which was one of Mr. Stevenson’s favourite recreations.