Полная версия:

Men-of-War

MEN-OF-WAR

Patrick O’Brian

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This eBook edition published 2019

Men-of-War copyright © The Estate of the late Patrick O’Brian CBE 1974

Patrick O’Brian asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover Image © Geoff Hunt 2019

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008328320

Ebook Edition © October 2019 ISBN: 9780008356002

Version: 2019-09-30

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

The Ships

The Guns

The Ship’s Company

Life at Sea

Songs

Index

About the Author

The Works of Patrick O’Brian

About the Publisher

Introduction

Since Britain is an island, it has always needed a navy to keep enemies from coming over the sea to invade it. If there had been an efficient navy in Roman times neither Caesar nor Claudius could have crossed the Channel; if there had been one in 1066, William would never have been called the Conqueror; and if there had not been one in the Armada year the British might be speaking Spanish now. Without the Royal Navy to stop him, Napoleon would certainly have invaded England in 1805 (he had 2,293 vessels in the Channel ports ready to carry 161,215 men and 9,059 horses across), just as Hitler would have done in 1940.

Then again, since England has been a trading nation time out of mind, it has always needed a navy to protect its merchant ships and to attack the enemy’s sea-borne trade. And ever since England became an industrial country as well, unable to produce enough food for its greatly increased population, a navy has been essential to prevent its being starved into surrender.

A navy has always been necessary; but it was not for many centuries after King Alfred’s time that the Royal Navy as we know it, a permanent service quite separate from the mercantile marine, came into being. The kings generally had some ships of their own, but in war most of the country’s naval force was made up of merchantmen, some hired and some provided by such towns as the Cinque Ports; and once the war was over they went home: they were not real men-of-war, in the sense of being ships specially built and armed for fighting alone. ‘Man’ is an odd word for a ship, since sailors call all vessels ‘she’, but ‘man-of-war’ came into the language about 1450, and it has stayed, together with East-Indiaman for a ship going to India or Guineaman for one sailing to West Africa, and many more. Henry VIII had about fifty men-of-war, and it was he who set up the Admiralty and Navy Board to look after them. Queen Elizabeth I had fewer – of the 197 English ships that sailed to fight the Spanish Armada only 34 belonged to her. Charles I had 42, but in the wars of the Commonwealth the number grew, so that when King Charles II came into his own again he had 154 vessels of all kinds. It was at this time that the Navy began to take on its modern shape: formerly the King had had to keep his ships out of his own pocket, but now the nation paid for them; and now the officers, instead of being sent away when there was no need for them, were kept on half-pay – they could make a career of the Navy rather than join from time to time. This did not apply to the men, however: they came aboard, or were brought aboard by the press-gang, every time there was a war; and when it was over they went back to their former ways of making a living. By the end of Charles II’s reign the Royal Navy had 173 vessels, and because of the labours of Samuel Pepys, the Secretary of the Admiralty, and of the Duke of York, who was Lord High Admiral, it was a fairly efficient body.

All through the eighteenth century the Royal Navy grew: in 1714 there were 247 ships amounting to 167,219 tons; in 1760 412 of 321,104 tons; and in 1793, although the number had dropped by one, the tonnage amounted to 402,555. This was at the beginning of the great war with France, in which the Royal Navy reached the height of its glory, and the numbers increased rapidly; by the time Napoleon had been dealt with, Britain had no less than 776 vessels, counting all she had taken from the French, Spaniards, Danes and Dutch; and altogether they came to 724,810 tons. At this time, at its greatest expansion, the Royal Navy needed 113,000 seamen and 31,400 Royal Marines, and a hard task it was to find them, as we shall see when we come to the press-gang.

The Ships

The vessels that made up the early Navy were of all shapes and sizes, from Henry VIII’s Henry Grace à Dieu of 1,000 tons down to row-barges, passing by cogs, carracks, and ballingers, shallops and pinnaces; but by the seventeenth century the pattern that lasted up until the coming of steam was clear, and by the eighteenth it was firmly established. The ships of the Royal Navy were divided into six rates as early as Charles I, and this is how they stood in 1793:

first rate 100–112 guns, 841 men (including officers, seamen, boys and servants) second rate 90–98 guns, 743 men third rate 64, 74 and 80 guns, 494, about 620, and 724 men fourth rate 50 guns, 345 men (this rate also included 60-gun ships, but there was none in 1793) fifth rate 32, 36, 38 and 44 guns, 217–297 men sixth rate 20, 24 and 28 guns, 138, 158 and 198 men.All these ships, from 20 to 112 guns, were commanded by post-captains.

Vessels that carried less than 20 guns – that is to say, all the sloops, brigs, bomb-ketches, fire-ships, cutters and so on – were not rated, and their captains were masters and commanders in the case of sloops, and lieutenants in the rest. (‘Captains’ in the sense of commanding officers, not of permanent rank: if a midshipman was sent away in charge of a prize, he was her captain so long as he was in command.)

The ships that carried 60 guns and more were called ships of the line, because it was they alone that could stand in the line of battle when two fleets came into action. The first and second rates were three-deckers (that is to say they had three whole decks of guns, apart from those on the quarterdeck and forecastle); the third and fourth rates and the 44s were two-deckers; and the rest one-deckers – they were frigates from 38 guns down to 26, and post-ships when they carried 24 or 20. The word ‘frigate’ was used in the seventeenth century without any very precise meaning, but by this time it had long been understood to mean a ship that carried her main armament on one deck and that was built for speed: the frigates were the eyes of the fleet, and they were also excellent cruisers, capital for independent action.

In 1793, counting those that were being built or repaired, those that were laid up and those that were stationary harbour ships, the Royal Navy had 153 ships of the line, 43 50- and 44-gun two-deckers, 99 frigates, and 102 unrated vessels.

I say vessels rather than ships because, although a vessel means anything that floats or is meant to float, for a sailor a ship is something quite distinct: it is a vessel, of course, but it is a square-rigged vessel with three masts (fore, main and mizen) and a bowsprit; what is more these three masts must be made up of a lower-mast, topmast and topgallantmast, and anything with only two masts (such as a brig) or with three all in one piece (such as a polacre) that presumed to call itself a ship would have been laughed to scorn, hooted down, given no countenance whatsoever.

The most usual line-of-battle ship was the 74: there were 73 of them at the beginning of the war and 137 in 1816. A 74 weighed about 1,700 tons and she needed some 2,000 oak trees to build her – 57 acres of forest. In the 1790s England could supply much of the wood, but as the years went by the forests began to look very thin, for an oak tree does not spring up overnight; and at least half the timber had to be imported. It was always oak, the very best oak, for nothing else would bear the terrible strain of the winter storms or the shock of battle: fir was tried for frigates and cedar for smaller craft, but it did not answer – heart of oak was the only thing for a man-of-war. Masts and yards had to be imported too: they were made of fir, and they had to be very long and straight. The mainmast of a first-rate was made up of three sections 117, 70 and 35 feet long, while her main yard was 102 feet across – such trees could be found in large numbers only in America or the north.

The building of a man-of-war was a highly-skilled, long and complicated business that I could not describe in less than ten volumes, but roughly this is how they set about it. First the ship was worked out on paper, sometimes following the plans of the beautiful and fast-sailing French or Spanish ships that were captured; then a model might be made, usually to the scale of a quarter of an inch to the foot (there are a great many of these models in the Maritime Museum at Greenwich and several in the London Science Museum); and then the keel would be laid, generally in one of the royal dockyards but sometimes in private shipbuilders’ yards. The keel was a massive assembly of elm, and to this were fixed the great rib-like oak timbers, first the stem (in front) and then the stern-post to take the rudder; then came the midship floor-timber and all the rest of the ship’s framework. When this was done the ribs were planked inside and out and the beams laid across. The decks were laid on the beams, with proper places for the masts, and when the hull was finished it was divided up by bulkheads into store-rooms, powder-magazines, cabins and so on, with ladders for going up and down, and the whole of the hull that was to be under water was coppered against the attacks of the teredo, a sea-worm that used to pierce holes right through the bottom, before this plating was thought of halfway through the eighteenth century.

All this took a long time – the Victory, for example, was laid down in 1759 but not launched until 1765 – and seeing that the wood was out in all weathers it often began to rot even before the ship was finished. The truth of the matter is that most of the British ships were not nearly so well built as the French or Spanish: they were often slow; they nearly always carried too many guns; they were sometimes very crank – that is, they leaned over in a wind so that they could not open the lower gun-port or the sea would rush in; and occasionally they fell to pieces in a storm. Among the worst were the Forty Thieves, forty ships of the line that were all built in private yards by dishonest contractors, and that were looked upon as floating coffins: but sometimes the royal yards were not much better. Nevertheless the Royal Navy won all the great fleet battles and nearly all the smaller actions between ships of roughly equal force. They did so partly out of force of habit, partly by better gunnery, and even more by better seamanship – you can only learn to be a sailor at sea, and the English Navy was at sea all the year round, whatever the weather, whereas the French and Spaniards were shut up in their harbours.

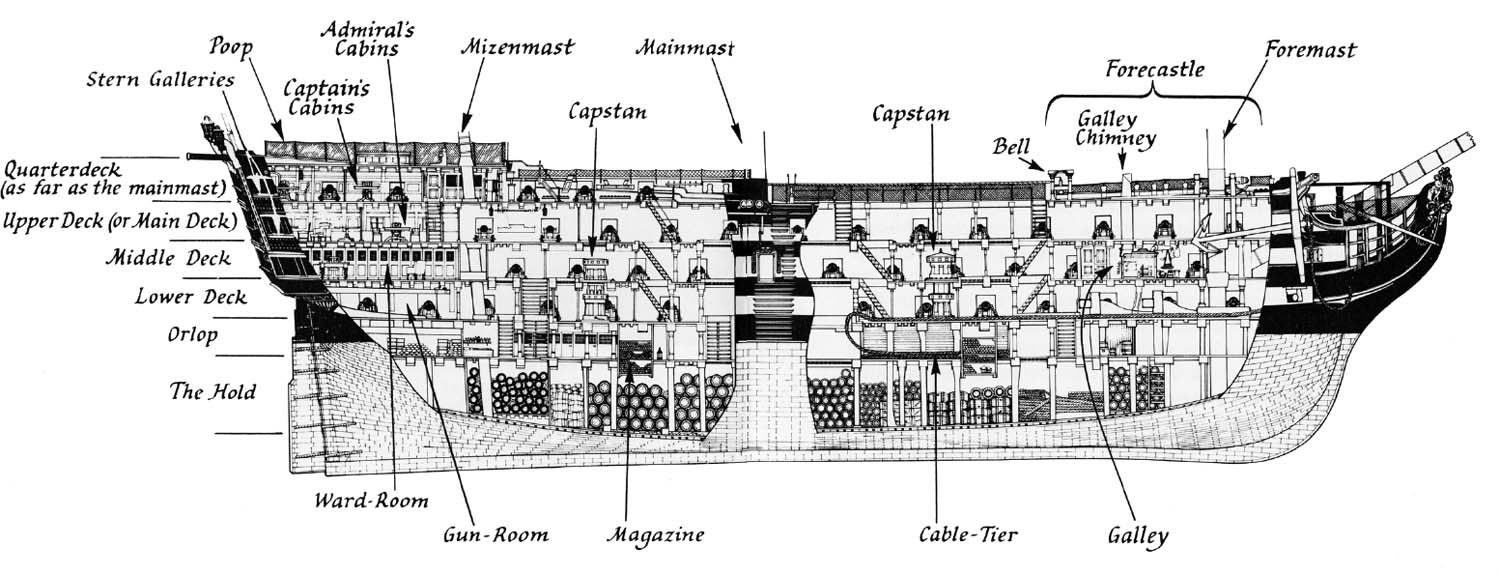

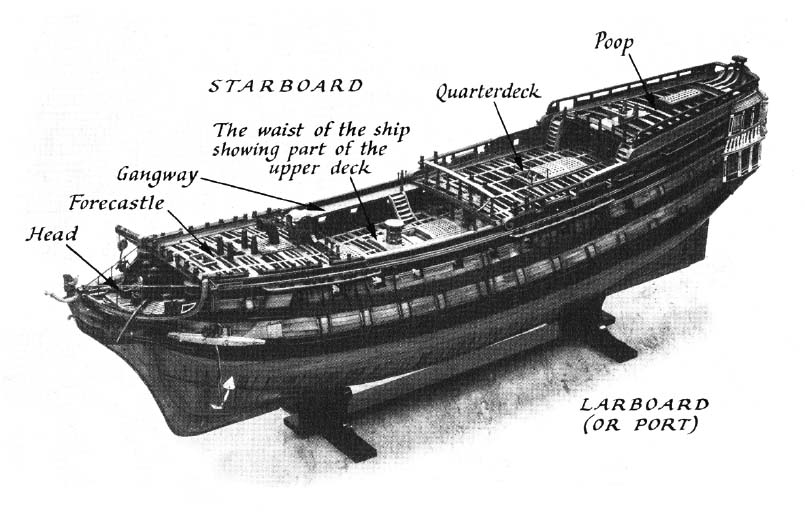

Now I will say something about the decks, and the sails and rigging, although the pictures show these things better than any number of words. Suppose we were transported to the bottom of a three-decker: we should be in the hold, a vast dark space about 150 feet long, 50 wide and 20 high, with curving sides, with a good many rats in it and a horrible smell of bilge-water – no fresh air and no light, because it would be well under the water-line. Most of it would be taken up with ballast, fresh water in casks, casks of salt pork and beef – enough to feed eight hundred men for six months – the cloth-lined powder magazine, the tin-lined bread-room, and all sorts of other stores. Overhead would be the orlop-deck, near the water-line. Right aft on the orlop was the cockpit, where the older midshipmen lived and where the wounded were treated in battle; forward of the cockpit were cabins for the junior officers – little dark, airless cupboards; then the sail-room with the spare sails; then the cable-tiers, where the great cables were stowed (some were 25 inches round, and all were 101 fathoms long); then the fore-cockpit where the boatswain and carpenter had their cabins and store rooms. Above the orlop was the lower deck, where the first and heaviest tier of guns stood in two rows facing their gun-ports, 32-pounders, weighing nearly three tons apiece. This was also called the mess-deck, for here the seamen ate and slept. Right aft lay the gun-room, where the gunner lived and where the junior midshipmen slung their hammocks; and right forward was the manger, a compartment designed to prevent the water that came through the hawse-holes from sweeping along the deck – it was also the place where the ship’s pigs, sheep and cattle were kept. Above the lower deck came the middle deck, with its rows of 24-pounders; and above that the upper or main deck, with its 18-pounders. The ward-room, where the senior officers messed, was at the after end, and their cabins usually opened off it. Still higher, from the stern to the mainmast, ran the quarterdeck, and on the same level as the quarterdeck, from the foreshrouds to the bows, the forecastle, the one with ten 12-pounders and the other with two: the quarterdeck and forecastle were connected by gangways. Lastly, above the after part of the quarterdeck, from the mizenmast to the stern, there was the poop, the roof of the captain’s quarters – his sleeping cabin, his fore-cabin, and his beautiful great after-cabin which opened on to a stern-gallery (very like a balcony) where he could walk and admire the view in privacy.

A first-rate ship, the Victory, in cross-section.

But here we are speaking of a first-rate, a three-decker, and many three-deckers were flagships – that is, they had an admiral aboard. When this was so, the great man occupied the after end of the main deck, just under the captain, and the lieutenants and their wardroom moved down to the middle deck.

In the case of two-deckers, the arrangement was much the same, only the middle deck was left out; but in one-deckers, such as frigates, there was no poop – the captain’s cabin was under the quarterdeck, on the main deck, and the lieutenants took over the gun-room on the deck below for their mess, banishing the gunner to a cabin forward and the younger midshipmen to the cockpit.

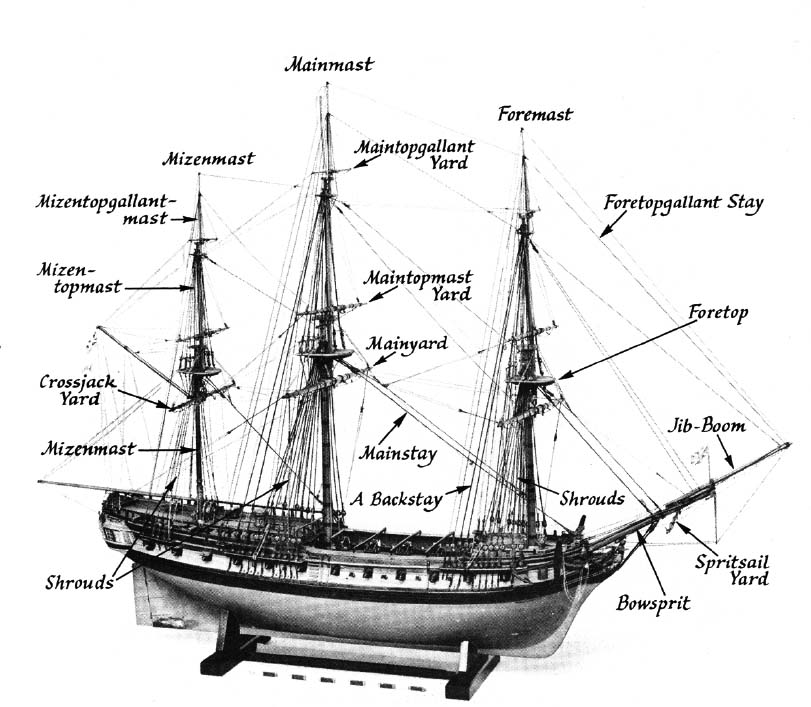

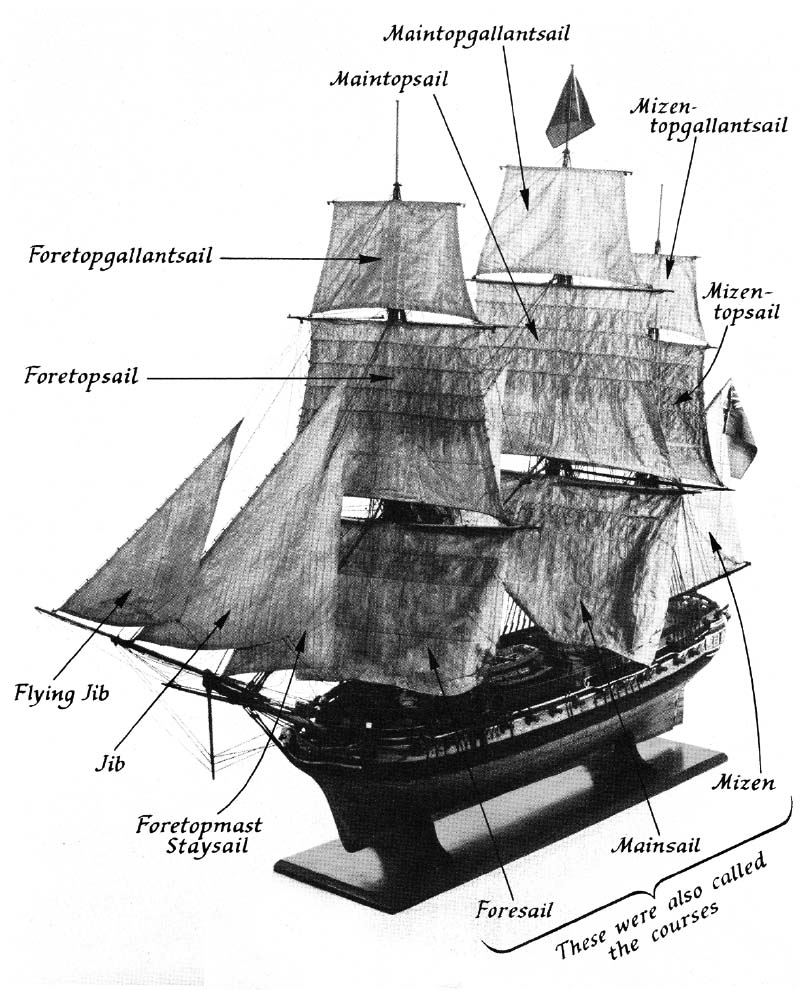

Masts, yards and rigging on a 28-gun frigate.

Now for the sails and the rigging. A square-rigged ship had three masts, of course, and these masts were held up by shrouds on each side, by stays to keep them from pitching backwards, and by back-stays to keep them from pitching forward: the shrouds had ratlines across them, to make ladders up which the seamen could climb to reach the upper rigging and the sails; and the first set of shrouds led to the platform called the top, or fighting-top, which stood at the junction of the lower-mast and topmast and which served to spread the shrouds for the next section of mast – these masts, by the way, were made to slide up and down through the top, so that in an emergency the topgallantmasts and even topmasts could be struck down on deck. The masts had yards slung across them horizontally, and it was to these yards that the most important sails were attached. The mainmast had a mainyard for the mainsail, a maintopmast yard for its topsail, a maintopgallant yard, and above that, in fine weather, a royal yard: the foremast had the same four yards with fore tacked on to their names: the lowest yard on the mizen, however, was called the crossjack, which hardly ever had a sail spread on it, because the chief sail on the mizen was a fore-and-aft sail spread by a gaff or lateen over the poop; the rest of its yards were the same. The bowsprit too had its yards and sails – the spritsail and the spritsail-topsail. There were other sails spread on the stays and various booms, but these were the important ones.

Sails on a frigate.

A two-decker with her bowspirit and masts out and her deck-planking removed to show the construction.

When the wind was from behind and the sails were spread, obviously the ship was pushed forward – not that this was the best point of sailing, because if the breeze were right astern, the after sails would becalm the rest, whereas if it came from her quarter, or 45° abaft the beam, it would fill them all. But when the wind came from the beam, that is to say sideways, or at right-angles to the ship’s length, then the square sails would have been useless unless they could swing round to catch its force. And of course that is what happened: the yards were pulled round with braces and the lower corners of the sails were hauled round too – the sheet on the lower leeward corner was hauled aft and the tack, the rope on the windward lower corner, was hauled forward, so that the sail continued to draw; and seeing that the ship could not be forced sideways through the water it went on going forward, though a little sideways too – this sideways motion was called its leeway. Indeed, even when the wind was more from in front than sideways, the ship could still go on: a square-rigged ship, close-hauled, that is, with her yards braced up sharp to an angle of 20° with the keel, could sail within six points of the wind, or 63° 45' from it – or in other words, if the wind were coming from the north, she could still sail east-north-east.

So much for the ships: now for the guns.

The Guns

The early guns had beautiful names like cannon-royal, cannon-serpentine, demi-culverin and falconet, but they had a bewildering variety of shot and charge; and since these weapons, together with basilisks, sakers and murdering-pieces might all be mounted on the same deck, it led to sad confusion in time of battle.

By the eighteenth century there were many fewer kinds, and they were called by the weight of the shot they fired: a first-rate, for example, carried 30 32-pounders on her lower deck, 28 24-pounders on her middle deck, 30 18-pounders on her upper deck, 10 12-pounders on her quarterdeck and 2 on her forecastle, thus firing a broadside of 1,158 lb. Everything was plain and straightforward: each deck had guns, shot, cartridges and wads of the same size; the guns could be supplied from the magazines as fast as the powder-boys could run; and all that remained was to fire them as quickly and accurately as possible.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги

Всего 10 форматов