скачать книгу бесплатно

From the great Darwin she learned that the visible world is an accumulation of facts, conditions: results. To understand the world you must reverse course, to discover the processes by which these results come into being.

By reversing the course of time (so to speak) you acquire mastery over time (so to speak). You learn that “laws” of nature are not mysteries but knowable as the exits on Interstate 75 traversing the State of Michigan north and south.

Is it unjust, ironic?—that catastrophe in one life (the ruin of E.H.) precipitates hope and anticipation in others (Milton Ferris’s “memory” lab)? The possibility of career advancement, success?

It is the way of science, Margot thinks. A scientist searches for her subject as a predator searches for her prey.

At least, no one had introduced the encephalitis virus into Elihu Hoopes’s brain with the intention of studying its terrible consequences, as Nazi doctors might have done; or performed radical psychosurgery on him for some presumably beneficial purpose. Chimps and dogs, cats and rats have been so experimented upon, in great numbers, and for a while in the 1940s and 1950s there’d been a vogue of prefrontal lobotomies on hapless human beings, with frequently catastrophic (if not very accurately recorded) results.

Sometimes the radical changes caused by lobotomies were perceived, by the families of the patients at least, to be “beneficial.” A rebellious adolescent becomes abruptly tractable. A sexually adventurous adolescent (usually female) becomes passive, pliant, asexual. An individual prone to outbursts of temper and obstinacy becomes childlike, docile. “Beneficial” for family and for society is not always so for the individual.

In the case of Elihu Hoopes it seems likely that a personality change of a radical sort had been precipitated by his illness, for no adult male of E.H.’s achievement and stature would be so trusting and childlike, so touchingly and naively hopeful. You have the uneasy feeling, in E.H.’s presence, that here is a man desperate to sell himself—to be liked. The change in E.H. is allegedly so extreme that his fiancée broke off their engagement within a few months of his illness, and E.H.’s family, relatives, friends visit him ever less frequently. He lives in the affluent Philadelphia suburb Gladwyne with an aunt, the younger sister of his (deceased) father, herself a “rich” widow.

From personal experience Margot knows that it is far easier to accept a person ravaged by physical illness than one ravaged by memory loss. Far easier to continue to love the one than the other.

Even Margot who’d loved her “great-grannie” so much as a little girl had balked at being taken to visit the elderly woman in a nursing home. This is not something of which Margot is particularly proud, and so she has begun a process of forgetting.

But E.H. is very different from her elderly relative suffering from (it would be diagnosed after her death) Alzheimer’s. If you didn’t know the condition of E.H. you would not immediately guess the severity of his neural deficit.

Margot wonders: Was E.H.’s encephalitis caused by a mosquito bite? Was it a particular species of mosquito? Or—is it a common mosquito, itself infected? In what other ways is herpes simplex encephalitis transmitted? Have there been other instances of such infections in the Lake George, New York, region? In the Adirondacks? She supposes that research scientists in the Albany area are investigating the case.

“How horrible! The poor man …”

It is the first thing you say, regarding E.H. When you are safely out of his earshot.

Or rather, it is the first thing Margot Sharpe says. Her lab colleagues are more adjusted to E.H. for they have been working with him for some time.

Nervously Margot smiles at the stricken man, who does not behave as if he understands that he is stricken. She smiles at him, which inspires him to smile at her, with a flash of something like familiarity. (She thinks: He isn’t sure if he should know me. He is looking for cues from me. I must not send him misleading cues.)

Margot is new to such a situation. She has never been in the presence of a living “subject.” She can’t help but feel pity for E.H., and horror at his predicament: how abruptly Elihu Hoopes was transformed from being an attractive, vigorous, healthy man in the prime of life to a man near death, losing more than twenty pounds, white blood count plummeting, extreme anemia, delirium. A herpes simplex infection resulting in encephalitis is so rare, E.H. might more readily have been struck by lightning.

Yet E.H.’s manner isn’t at all guarded, wary, or stiff; he might be a host welcoming guests to his home, whose names he doesn’t quite recall. Indeed he seems at home in the Institute setting—at least, he doesn’t seem disoriented. For these sessions at the Institute E.H. is brought from his aunt’s suburban home near Philadelphia by an attendant, in a private car; originally E.H. was a patient at the Institute, and then an outpatient; he is still under the medical care of Institute staff. Though E.H. recognizes no one, yet it is flattering to him, how so many people recognize him.

He seems to have little capacity for brooding, as he has lost his capacity for self-reflection. Margot is touched by the way he pronounces her name—“Mar-go”—as if it were a beautiful and unique name and not a harsh spondee that has always somewhat embarrassed her.

Though Milton Ferris hasn’t intended for the introduction of his youngest lab member to be anything more than a fleeting pro forma gesture, E.H. takes pleasure in drawing out the ritual. He shakes her hand in a way both courtly and caressing. And unmistakably he leans close to Margot as if inhaling her.

“Welcome—‘Margot Sharpe.’ You are a—new doctor?”

“No, Mr. Hoopes. I’m a graduate student in Professor Ferris’s lab.”

Quickly E.H. amends: “‘Graduate student—Professor Ferris’s lab.’ Yes. I knew that.”

In an enthusiastic voice E.H. repeats Margot’s words precisely, as if they were a riddle to be decoded.

Individuals who are memory-challenged can contend with the handicap by repeating facts or strings of words—“rehearsing.” But Margot wonders if E.H.’s repetitions carry with them comprehension, or only rote mimicry.

To the brain-damaged man, much in ordinary life must be fraught with mystery at all times—where is he? What is this place? Who are the people who surround him? Beyond these perplexities is the larger, greater mystery of his very existence, his survival after near-death, which is (Margot supposes) too profound for him to consider. The amnesiac with a very limited short-term memory is like one who stands so close to a mirror that his face is virtually pressed against it—he cannot “see” himself.

Margot wonders what E.H. sees, looking into a mirror. Is his face a surprise to him, each time? Whose face?

It is touching, too—(though this might be attributable to the man’s neurological deficit and not his gentlemanly nature)—that, in his attitude toward his visitors, E.H. makes no distinction between the least consequential person in the room (Margot Sharpe) and the most consequential (Milton Ferris); he has lost his instinctive capacity for ranking. It isn’t clear what he makes of Ferris’s other assistants, or rather “associates” (as Ferris would call them: de facto they are “assistants”) whom he has met before: another, older female graduate student, several postdoctoral fellows, and an allegedly brilliant young assistant professor who is Ferris’s protégé at the Institute and has published several important papers with him in neuroscience journals.

E.H. is slow to surrender Margot Sharpe’s hand. He continues to stand close beside Margot as if surreptitiously sniffing her hair, her body. Margot is uneasy, for she doesn’t want to annoy Milton Ferris; she knows that her supervisor is waiting for an opportunity to initiate the morning’s testing, which will require several hours in the Institute testing-room, even as E.H. in his concentration upon the young, black-haired, attractive woman seems to have forgotten the reason for his guests’ visit.

(It occurs to Margot to wonder if a brain-damaged person might be likely to compensate for memory loss with a heightened olfactory sense? A plausible and exciting possibility which she might one day explore, Margot thinks.)

(The amnesiac subject is clearly far more interested in Margot than in the others—she hopes that his interest isn’t just frankly sexual. It occurs to her to wonder if the subject’s sexuality has been affected by his amnesia, and in what way …)

But E.H. speaks to her in a kindly manner, as if she were a young girl.

“‘Mar-go.’ I think you were in my grade school class at Gladwyne Day—‘Mar-go Madden’—unless it was ‘Margaret Madden’ …”

“I’m afraid not, Mr. Hoopes.”

“No? Really? Are you sure? This would have been in the late 1930s. In Mrs. Scharlatt’s sixth-grade class you sat at the front, far left by the window. You had silver barrettes in your hair. Margie Madden.”

Margot feels her face heat. It is just not the flirtation that makes her uneasy but a kind of complicity of hers, as of the others who are listening, in their reluctance to tell E.H. frankly of his condition.

It would be Dr. Ferris’s obligation to tell him this; or rather, to tell him again. (For E.H. has been told many times.)

“I—I’m afraid not …”

“Well! Will you call me ‘Eli’? Please.”

“‘Eli.’”

“Thank you! That’s very kind.”

E.H. consults a little notebook he keeps in a pocket of his khakis, and jots down a note. He holds the notebook at a slight, subtle angle so that no one can see what he is writing; yet not so emphatically an angle that the gesture is insulting to Margot.

Margot has been told that the amnesiac has been keeping notebooks since he’d recovered from his illness and was strong enough to hold a pen in his hand. So far he has accumulated many dozens of these small notebooks as well as sketchbooks measuring forty-eight inches by thirty-six inches; he never arrives at the Institute without both of these. Apparently the notebook and the sketchbook serve different functions. In the notebooks E.H. jots down stray facts, names, times and dates; he inserts columns torn from magazines and newspapers from the fourth-floor lounge. (Male staffers who use the fourth-floor men’s restroom report finding such detritus there each day that E.H. is on the premises—that is how they know, they say, that “your fancy amnesiac” has been there.) The sketchbooks are for drawings.

The complex neurological skills needed for reading, writing, and mathematical calculation seem not to have been much affected by E.H.’s illness, as they were acquired before the infection. So E.H. reads brightly from the notebook: “‘Elihu Hoopes attended Amherst College and graduated summa cum laude with a double major in economics and mathematics … Elihu Hoopes has attended Union Theological Seminary and has a degree from the Wharton School of Business.’” E.H. reads this statement as if he has been asked to identify himself. Seeing his visitors’ carefully neutral expressions he regards them with a little tic of a smile as if, for just this moment, he understands the folly and pathos of his predicament, and is begging their indulgence. Forgive me! The amnesiac has learned to gauge the mood of his visitors, eager to engage and entertain them: “I know this. I know who I am. But it seems reasonable to check one’s identity frequently, to see if it is still there.” E.H. laughs as he snaps the little notebook shut and slips it back into his pocket, and the others laugh with him.

Only Margot can barely bring herself to laugh. It seems to her cruel somehow.

There is laughter, and there is laughter. Not all laughter is equal.

Laughter too depends upon memory—a memory of previous laughter.

Dr. Ferris has told his young associates that their subject “E.H.” will possibly be one of the most famous amnesiacs in the history of neuroscience; potentially he is another Phineas Gage, but in an era of advanced neuropsychological experimentation. In fact E.H. is far more interesting neurologically than Gage whose memory had not been severely affected by his famous head injury—the penetration of his left frontal lobe by an iron rod.

Dr. Ferris has cautioned them against too freely discussing E.H. outside their laboratory, at least initially; they should be aware of their “enormous good fortune” in being part of this research team.

Though she is only a first-year graduate student Margot Sharpe doesn’t have to be told that she is fortunate. Nor does Margot Sharpe need to be told not to discuss this remarkable amnesiac case with anyone. She does not intend to disappoint Milton Ferris.

Ferris and his assistants are preparing batteries of tests for E.H., of a kind that have never before been administered. The subject is to remain pseudonymous—“E.H.” will be his identity both inside and outside the Institute; and all who work with him at the Institute and care for him are pledged to confidentiality. The Hoopes family, which has donated millions of dollars to the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Medicine, has given permission exclusively to the University Neurological Institute at Darven Park for such testing so long as E.H. is willing and cooperative—as indeed, he appears to be. Margot doesn’t like to think that a kicked dog, yearning for human approval and love, desperate for a connection with the “normal,” could not be more eagerly cooperative than the dignified Elihu Hoopes, son of a wealthy and socially prominent Philadelphia family.

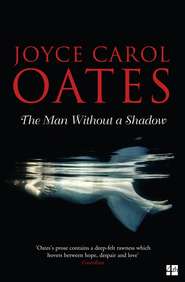

Elihu Hoopes is trapped in a perpetual present, Margot thinks. Like a man wandering in circles in a twilit woods—a man without a shadow.

And so he is thrilled to be saved from such a twilight and made the center of attention even if he doesn’t know quite why. How otherwise does the amnesiac know that he exists? Alone, without the stimulation of attentive strangers asking him questions, even the twilight would fade, and he would be utterly lost.

“‘MARGO NOT-MADDEN’?—THAT is your name?”

At first Margot can’t comprehend this. Then, she sees that E.H. is attempting a sort of joke. He has taken out his little notebook again, and has painstakingly inscribed in it what appears to be a diagram in logic. One category, represented by a circle, is M M and a second category, also represented by a circle, is M Not-M. Between the two circles, which might also be balloons, since strings dangle from them, is a broken line.

“My days of mastering symbolic logic seem to have abandoned me,” E.H. says pleasantly, “but I think the situation is something like this.”

“Oh—yes …”

How readily one humors the impaired. Margot will come to see how, within the amnesiac’s orbit, as within the orbit of the blind or the deaf, there is a powerful sort of pull, depending upon the strength of will of the afflicted.

Still, Margot is uncertain how to respond. It is a feeble and somehow gallant attempt at humor but she doesn’t want to encourage the amnesiac subject in prevarication—she knows, without needing to be told, that her older colleagues, and Milton Ferris, will disapprove.

Also, an awkward social situation has evolved which involves caste: the (subordinate) Margot Sharpe has supplanted, in E.H.’s limited field of attention, the (predominant) Milton Ferris. It is even possible that the brain-damaged man (deliberately, craftily) has contrived to “neglect” Dr. Ferris who stands just at his elbow waiting to interrupt—(“neglect” is a neurological term referring to a pathological blindness caused by brain damage); and so it is imperative that Margot ease away from E.H. so that Ferris can reassert himself as the (obvious) person in authority. Margot hopes to execute this maneuver as inconspicuously as possible without either the impaired man or the distinguished neuropsychologist seeing what she is doing.

Margot doesn’t want to hurt E.H.’s feelings, even if his feelings are fleeting, and Margot doesn’t want to offend Milton Ferris, the most distinguished neuroscientist of his generation, for her scientific career depends upon this fiercely white-bearded individual in his late fifties about whom she has heard “conflicting” things. (Milton Ferris is the most brilliant of brilliant scientists at the Institute but Milton Ferris is also an individual whom “you don’t want to cross in any way, even inadvertently. Especially inadvertently.”) As a young woman scientist, one of very few in the Psychology Department at the University, Margot knows instinctively to efface herself in such circumstances; as an undergraduate at the University of Michigan with a particular interest in experimental cognitive psychology, she absorbed such wisdom through her pores.

Also, it was abundantly clear: there were virtually no women professors in the Psychology Department, and none at all in Neuroscience at U-M.

Margot is not a beautiful young woman, she is sure. She has a distrust of conventional “beauty”—her more attractive girl-classmates in school were distracted by the attention of boys, in several cases their lives altered (young love, early pregnancies, hasty marriages). But Margot considers herself a canny young woman, and she is determined not to make mistakes out of naïveté. If E.H. is a kind of dog in his eagerness to please, Margot is not unlike a dog rescued from a shelter by a magnanimous master—one who must be assured, at all times, in the most subtle ways possible, that he is indeed master.

In his steely jovial way Milton Ferris is explaining to E.H. that Margot is “too young” to have been a classmate of his in the late 1930s—“This young woman from Michigan is new to the university and new to our team at the Institute where she will be assisting us in our ‘memory project.’”

E.H. frowns thoughtfully as if he is absorbing the information packed into this sentence. Affably he concurs: “‘Michigan.’ Yes—that makes it unlikely that we were classmates at Gladwyne.”

In the same way E.H. is trying to behave as if the term “memory project” is familiar to him. (Margot wonders if this persuasive and congenial persona has been a nonconscious acquisition in the amnesiac. She wonders whether testing has been done in the acquisition of such “memory” by individuals as brain-damaged as E.H.)

As Milton Ferris speaks expansively of “testing,” E.H. exhibits eagerness and enthusiasm. Over the course of the past eighteen months he has been tested countless times by neurologists and psychologists but it isn’t likely that he can remember individual sessions or tests. From before his injury he retains a general knowledge of what a “test” is—he knows what an “I.Q. test” is. From before his injury he might know that his I.Q. was once tested at 153, when he was eighteen years old; but he can’t know that, after his injury, his I.Q. has been tested several times, and has been measured in the range of 149 to 157. Still of superior intelligence, at least theoretically.

This is fascinating to Margot: E.H.’s pre-injury vocabulary, language skills, and mathematical abilities have survived more or less intact but (it is said) he can’t retain new words, concepts, or facts even if they are embedded in familiar information. He has been observed taking notes on the financial section of his favorite newspapers but when asked about what he has been inscribing a few minutes later he shrugs disdainfully—“Homo sapiens is the species that ‘makes’ and ‘loses’ money. What else is new?” He has forgotten what had so engrossed him but he can readily invent a substitute with which to disguise his memory loss.

At times E.H. seems to know that John F. Kennedy was assassinated recently—(two years ago)—while at other times E.H. speaks of “President Kennedy” as if the man were still alive—“Kennedy will need to revise his position on Cuba. He will need to lead the country out of the quagmire of Vietnam.”

And, grandiloquently: “Some of us are hoping to get to Washington, to meet with the president. The situation is getting more and more urgent.”

It would seem delusional except, as Ferris has noted, the Hoopes family of Philadelphia has long had ties with state and federal politicians.

Like many brain-afflicted individuals E.H. carries with him dictionaries and other word-books; he keeps long lists of words in his notebooks alphabetically arranged—that is, there are pages of A’s, B’s, C’s, and so forth. (E.H. takes pleasure in consulting these when he does the Times crossword puzzle as, his family has attested, he’d never consulted a dictionary when doing the puzzle before his illness.) His proficiency in math is impressive. His knowledge of world geography is impressive. He can discuss rival economic theories—Keynesian, classical, Marxist; he likes to expound upon von Neumann’s Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, key lines of which he has memorized. But if questioned he can only repeat more or less what he has already said; his ideas are fixed, like his vocabulary. No new ideas or revisions of the past can penetrate. And if he is challenged his affable nature vanishes and he becomes irritable, ironic. He is adept at board games and puzzles of a kind he’d mastered when he was a boy but he can’t easily learn new games.

Margot supposes that if E.H. could reason more clearly he would assume that the repeated tests he undergoes constitute a kind of treatment or therapy that might allay his condition; but he can’t know his “condition” though it has been explained to him repeatedly; and he can’t know that the tests are in fact “repeated” or that they are for the sake of experimental research—that’s to say for the sake of neuroscience and not for the sake of the subject.

Ferris is speaking carefully to E.H.: “Mr. Hoopes—Eli—let me explain again that I am a neuropsychologist who teaches at the University of Pennsylvania and these are members of my lab. We’ve been working with you for the past fifteen weeks here at the Institute at Darven Park, each Wednesday, and we have made some exciting preliminary discoveries. You have met me before, and we have gotten along splendidly! I am ‘Milton Ferris’—”

E.H. nods vehemently, even a little impatiently, as if he knows all this: “‘Mil-ton Fer-ris’—yes. ‘Dr. Ferris.’”

“I am not a ‘doctor’—I am a professor. I have a Ph.D. of course but that is not essential! Please just call me—”

“‘Professor Fer-ris.’ Yes.”

“And I have explained—I am not a clinician.”

This is a way of telling the subject I am not a medical doctor. You are not my patient.

But E.H. seems to purposefully misunderstand, awkwardly joking: “Well, Professor—that makes two of us. I am not a clinician, either.”

E.H. has spoken a little too loudly. Is this a way of signaling irritation with Professor Ferris? Since his attention has been forcibly removed from black-haired Margot Sharpe?

(Margot wonders too if E.H. is speaking quickly as if to signal, subliminally, that he isn’t much interested in the information that Milton Ferris is providing him; despite his severe amnesia E.H. “remembers” enough from previous exchanges to know that he won’t remember this information, either, thus resents being given it.)

While his visitors look on E.H. leafs through his little notebook until he comes to a crucial page. He smiles, showing the page to Margot rather than to Ferris—a drawing of two tennis players, one of them wildly flailing with his racket as a ball sails over his head. (Is this player meant to be E.H.? The player’s hair and features suggest that this is so. And the other player, with a blurred face and exaggerated grin, is meant to be—Death?)

“This—‘tennis’—I used to play. Pretty damned good on the Amherst team. Are we going to play ‘tennis’ now?”

“Eli, you’re an excellent tennis player. You can play tennis another day. But right now, if you’d like to take a seat, and …”

“‘Excellent’? Is that so? But I have not played tennis in a long time, I think.”

“In fact, Eli, you played tennis just last week.”

Eli stares at Ferris. This is not what Eli has expected to hear and he seems incapable of absorbing it but without missing a beat Ferris says in a warm and uplifting voice, “Now, Eli, you’ve always trounced me. And it has been reported to me not only that you’d played with one of the best players on the staff but you’d won each game.”

“‘Reported’—really!”

E.H. laughs, faintly incredulous.

Margot sees: the poor man is feeling the unease of one being made to understand that the most complete knowledge of himself can come only from the outside—from strangers.

A melancholy conviction, Margot thinks, to realize that you can’t know yourself as reliably as strangers can know you!

Patiently Milton Ferris explains to E.H. why he has been brought to the Institute that morning, and why Ferris and his laboratory are going to be “testing” him—as they’d done in the past; E.H. listens politely at first, then becomes bemused and beguiled by Margot whom he has rediscovered: she is wearing a black wraparound skirt with black tights beneath, a black jersey pullover that fits her petite frame tightly, and black ballerina flats—the clothes of a schoolgirl dancer and not the crisp white lab coats of the medical staff or the dull-green uniforms of the nursing staff. There is no laminated ID on her lapel to inform him of her name.

Annoyed, Ferris says: “Whenever you’d like to begin, Mr. Hoopes—Eli. That’s why we’re here.”

“Why you are here, Doctor. But why am I here?”

“You’ve enjoyed our tests in the past, Eli, and I think you will again.”

“That’s why I am here—to ‘enjoy’ myself?”

“We are hoping to establish some facts concerning memory. We are hoping to explore the question of whether memory is ‘global’ in the brain—not localized; or whether it is localized. And you have been helping us, Eli.”

“Have they kicked me out of the office?—has someone taken my place? My brother Averill, and my uncle—” E.H. pauses as if, for a vexed moment, he can’t recall the name of one of his Hoopes relatives, an executive at Hoopes & Associates, Inc.; then he rallies, with one of his enigmatic remarks: “Where else would I be, if I could be somewhere else?”

Milton Ferris assures E.H. that he is in “just the right place, at just the right time to make history.”

“Did I tell you? I’ve heard Reverend King speak. Several times. That is ‘history.’”