Полная версия:

The Scandalous Duchess

Praise for the author

ANNE

O’BRIEN

‘An absolutely gripping tale that is both superbly written and meticulously researched’

—The Sun

‘The characters are larger than life…and the author a compulsive storyteller. A little fictional embroidery has been worked into history, but the bones of the book are true.’

—Sunday Express

‘This book has everything–royalty, scandal, fascinating historical politics and, ultimately, the shaping of the woman who founded the Tudors.’

—Cosmopolitan

‘O’Brien has excellent control over the historical material and a rich sense of characterisation, making for a fascinating and surprisingly female-focused look at one of the most turbulent periods of English history.’

—Publishers Weekly

‘Better than Philippa Gregory’

—The Bookseller

‘Another excellent read from the ever-reliable Anne O’Brien. Strong characters and a great setting make this highly recommended.’

—The Bookbag

‘Anne O’Brien is fast becoming one of Britain’s most popular and talented writers of medieval novels. ’

—Lancashire Evening Post

‘A must-read for any historical fiction fan’

—The Examiner

‘Brings the origins of the most famous royal dynasty to vibrant life’

—Candis

‘I was keen to see if this book…lived up to the hype— which it did.’

—Woman

Also by

ANNE O’BRIEN

THE SHADOW QUEEN

THE QUEEN’S CHOICE

THE KING’S SISTER

THE SCANDALOUS DUCHESS

THE FORBIDDEN QUEEN

THE KING’S CONCUBINE

DEVIL’S CONSORT

VIRGIN WIDOW

The Scandalous Duchess

Anne O’Brien

ISBN: 978-1-472-01039-1

THE SCANDALOUS DUCHESS

© 2014 Anne O’Brien

Published in Great Britain 2014

by HQ, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street, London, SE1 9GF

All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. This edition is published by arrangement with Harlequin Books S.A.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, locations and incidents are purely fictional and bear no relationship to any real life individuals, living or dead, or to any actual places, business establishments, locations, events or incidents. Any resemblance is entirely coincidental.

By payment of the required fees, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right and licence to download and install this e-book on your personal computer, tablet computer, smart phone or other electronic reading device only (each a “Licensed Device”) and to access, display and read the text of this e-book on-screen on your Licensed Device. Except to the extent any of these acts shall be permitted pursuant to any mandatory provision of applicable law but no further, no part of this e-book or its text or images may be reproduced, transmitted, distributed, translated, converted or adapted for use on another file format, communicated to the public, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of publisher.

Version: 2018-02-07

To George, who for a whole year tolerated having to play second fiddle to John of Lancaster, but knows that he always remains my hero.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

All my thanks to my agent, Jane Judd, whose love of history is as strong as my own. Her support and encouragement for me and the courageous women of the Middle Ages continues to be invaluable.

To Sally Williamson at HQ whose empathy with what I wish to say about my characters is beyond price. To her and to all the staff at HQ, without whose advice and professional commitment the real Katherine Swynford would never have emerged from the mists of the past.

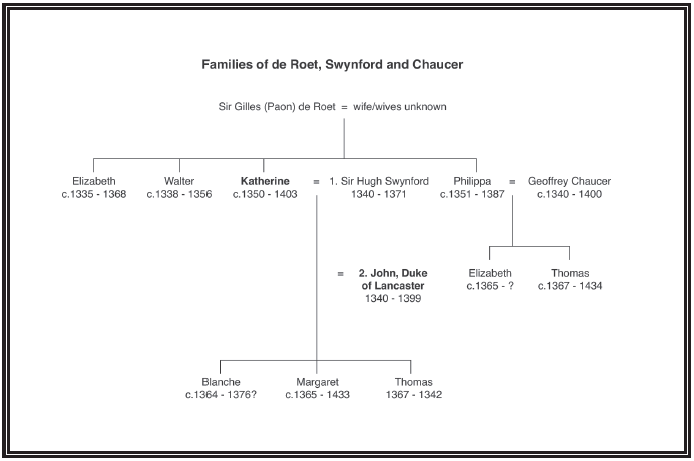

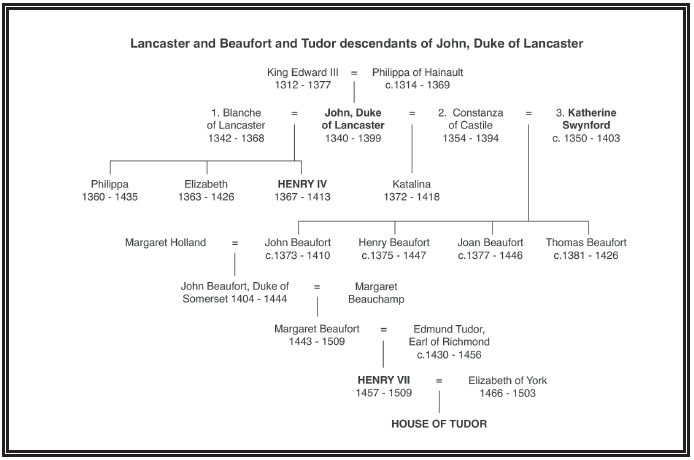

To Helen Bowden and all at Orphans Press, without whom my website would not exist and who create professional masterpieces out of the rough drafts of genealogy and maps I push in their direction.

‘…he [John, Duke of Lancaster] was blinded by desire, fearing neither God nor shame amongst men.’

Knighton’s Chronicle 1337-1396

‘…a she-devil and enchantress…’

The Anonimalle Chronicle 1333-1381

‘…an unspeakable concubine…’

Thomas Walsingham’s Chronicon Angliae

Table of Contents

Cover

Praise

Also by ANNE O’BRIEN

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Epilogue

Extract

AUTHOR NOTE

Read all about it…

MORE ABOUT THIS BOOK

About the Publisher

Prologue

January 1372: The Manor of Kettlethorpe, Lincolnshire

The water that had swamped the courtyard overnight, thanks to a sudden storm, soaked into my shoes. And then my stockings. I hitched my skirts, scowling at the floating debris around me. Even the chickens, isolated on a pile of wood in the corner, looked morose.

‘Who left that harness out?’ I demanded, seeing the coils of leather black and dripping on the hook beside the stable door. My servants, few as they were, had gone to ground, and since nothing could be done until the rain actually stopped, I squelched under cover again.

Kettlethorpe. My young son’s inheritance, and a poor one at that. The burden of it, since my husband’s recent death and the administration of the estate not yet settled, fell on my shoulders. I flexed them, my sodden, mud-daubed cloak lying unpleasantly around my throat. The shadow of a lively rodent caught my eye as it vanished behind the buttery screen.

‘What do I do?’ I asked aloud, then winced at the crack of despair in my voice.

There was no one to give me advice.

I imagined what Queen Philippa might have said to me. Raised by her, educated by her at the English court, the wife of King Edward the Third had been my model of perfect womanhood: a woman without physical comeliness, but with a beauty of soul that outmatched any I knew.

‘Duty, Katherine!’ she would have said. ‘It is for you to carry the burdens. You are twenty-two years old and Lady of Kettlethorpe. When you wed Sir Hugh Swynford you took on the responsibility of your position. You will not abandon it when your feet are wet and rats scurry around your ankles. That is not how I raised you. You have the tenacity to make something of Kettlethorpe, and you will.’

I sighed, the tenacity at a low ebb, even though I admitted the truth of her knowledge of me. No, of course I would not abandon it. That was not my way, for the Queen’s principles had been lodged firmly in my heart. What I did not have was the financial resource to improve my lot.

Despondent, I stepped to the centre of my hall where a fire burned with smouldering reluctance, and turned slowly round, pushing my hood back to my shoulders. The walls were running wet in places. The haze of smoke that never cleared tainted everything with acrid stench, for which there was no remedy that I could afford. I could not even think of installing a wall chimney.

‘God will give you his grace, and the Virgin her compassion. Go to your prie-dieu, Katherine.’ Queen Philippa again, framing my face with her hands as she imparted to me her own rigorous strength.

Certainly I would go to my knees before this day was out—was not the Blessed Virgin my solace in all adversity? But on this occasion I needed coin as much as the Virgin’s blessings. I rubbed my hands together, regretting the abrasions, the ugly burn on my wrist where one of the torches, flaring, had caught me unawares. Once my hands had been soft, my nails perfectly pared. Once my gown pleased me with the soft rustle of silk damask rather than the roughness of this coarse wool, the only cloth fit for the tasks that fell to me. Silk skirts did not sit well with wringing the neck of a scrawny fowl for dinner.

I sighed a little.

Once I had been honoured, chosen as a damsel in Duchess Blanche of Lancaster’s household. I covered my face with my hands, shutting out the images of that pampered life of luxury at The Savoy Palace, for here, around me, was the reality of my present existence. At The Savoy I never had to sweep up the evidence left by a pair of doves roosting in the rafters overnight and now shuffling into wakefulness. Now I clapped my hands, frightening them into flight and further fouling of the floor.

There was one remedy, of course, to all this destitution. Duchess Blanche was dead these past three years, but the Duke had a new wife. Would there not be a place for me there, where I might earn enough to put all to rights? Where I might, in ducal employ once again, acquire sufficient money to ensure a better home for my son to inherit?

Why not? Why should I not return to the world I knew and loved? Surely, given my previous experience, there was some role that I could fulfil. Queen Philippa would have sanctioned it as an eminently practical decision for me to make in the circumstances.

I flapped my hands to disperse the smoke and a few downy feathers that still hung in the air and marched across to the stairs, to climb to my private chamber where I cast aside the heavy cloak. Lifting the lid of my coffer, I sifted through the layers of court dress, the fragile cloth sadly marked with moth and mildew however careful my attention with lavender and sage leaves, and lifted out a much treasured mirror. Opening the ivory case, dull with disuse, I wiped the moisture from the glass on my bodice and looked.

I pursed my lips.

‘Who are you, Katherine de Roet?’ I asked.

Katherine de Swynford now, of course, married and widowed. Suddenly distracted, I turned my head. Children’s voices, raised in sharp complaint, sliced through the silence, but then dissolved into laughter, and I returned to my critical survey. I considered my hair, tightly braided and pinned, dark gold with damp, and dishevelled where the pins had come adrift under my hood. Darker brows took my eye. Once I might have plucked them into perfection, but no more. A rounded face, with soft cheeks and soft lips, a little indented at the corners with my present excess of emotion. A generous mouth, quick to smile, yet any softness there was belied by a direct stare. I raised my brows a little. No one would accuse me of shyness nor, brought up as I was in the strictest canons of propriety, of frivolity, yet I enjoyed all the comfort that wealth and consequence could bring, and to which I no longer had access.

And I wished with all my heart that I enjoyed that consequence again.

It was not a plain face that looked back at me. True, such enhancements as I might have worn at court were entirely absent. Indeed, it could have been, I decided, the face of one of my kitchen maids with that suspicion of dust along the edge of my jaw where I had rubbed at it with my sleeve. The mirror was misted again, and I polished it on my hip. They said I was beautiful. That I had the look of my late mother whom I had never known. Perhaps I was, although I thought my sister had more claims to beauty than I.

What was I looking for? What had driven me to resort to my mirror? Not the symmetry of my features, but to discover the woman behind them. I tilted my chin, considering what I might see.

Honesty, I hoped. Courage, to seize the opportunity to make more of my life. Not least a determination to live as I had been raised, with integrity and good judgement. That was what I hoped to see.

And perhaps I did see it, as well as the duty to my family name and honour to the Blessed Virgin that had marked every step of my life.

So I would go to The Savoy. I would petition the Duke in the name of my previous service to Duchess Blanche, accepting that I must relinquish my pride for I had a goodly measure of it—but I would do it, for my own sake as well as that of my children. If honesty was strong in me, I must accept that life in a desolate fastness, stretching out changelessly to the end of my days, filled me with dismay, whereas life within the royal court and ducal household with friends from the past beckoned with seductive fingers.

I smiled at the prospect, yet felt my pleasure fade. Replacing the mirror in my coffer, sifting through the words that had slipped through my mind, my heart fell a little at the sheer weight of them. Integrity. Restraint. Respectability. That was to be my life. That was what I knew. I would conduct myself as a respectable widow, unless I was fortunate, one day, to wed again. Queen Philippa would be proud of my strength of will to accomplish it.

My hands, in the act of closing my coffer, paused on the open lid of it, as if reluctant to shut away that reflection of the woman behind the familiar features. How dull, how colourless my chosen life sounded, as even-textured and familiarly unexciting as a line of plainchant. And how prim and prudish the woman who would live it. Was this me? Was this really what I wanted? It was as if I had decided to exist in shades of black and grey and religious observance, when energy, with sly enthusiasm, was surging though my whole body, opening up pictures in my mind of how it would be to sing and dance again, to be courted, to flirt, to exchange kisses in the company of a handsome man who desired me.

Perhaps this was the real Katherine de Swynford, lively and frivolous, thoroughly pleasure-loving, rather than a staid widow who looked for nothing in life but allowing the beads of her rosary to slide through her fingers as she petitioned the Virgin’s grace for herself and her children. The sheer thrill of returning to The Savoy, to a position in the Lancaster household, glowed even brighter in my mind.

And then, as if summoned by my delight, there was the image of the Duke of Lancaster himself, standing in my chamber with the light behind him, as clear as if he were really there, as the sun creates a fantasy when shining through raindrops.

Impressively tall. Impressively proud. Impressively everything.

I considered him in my mind’s eye: Duke John of Lancaster, a man I had known all my life, a man whom I admired. Admired. Yes—that was it, for was it not admiration? A man of wealth and power and striking appearance, the Duke attracted high regard and vilification in equal measure from those who crossed his path. Would I wish to live once again within his forceful presence? Well, why should I not? I might be overawed, overwhelmed by the extent of his authority and the sheer magnetism of his charisma, but I knew him for a man of unfailing chivalry too. He would not cast me adrift. Returning to The Savoy held no fears for me.

Opening my eyes, finding the bright image dispelled, I closed the coffer and locked it, before walking to my open door with a light heart despite my wet stockings, and called down the stairs to my steward.

‘Master Ingoldsby! A moment of your time, if you will.’

And enjoyed a shiver of excitement, such as I had not experienced for too long. I had more important tasks for my steward to supervise than sweeping up after my doves. I was going to The Savoy.

I realised that I was smiling again.

Chapter One

January 1372: The Savoy Palace, London

It was like a proclamation of royal decree. A command complete with banners, heralds and fanfare. Every muscle in my body tightened, my breath whistled in my throat on a sharp inhalation, and I was no longer smiling. I was not smiling at all.

His voice was impeccably courteous, but the words he uttered sliced through all the bother that had occupied my mind for the past two months with the precision of a rapier. I could not believe what he had just said to me. This Plantagenet prince, so unconsciously dramatic on this winter’s morning, had just carelessly shaken the ground on which I stood.

Yet was he carelessly unthinking? I looked at his face, to find his gaze direct and deliberate, enough to cause an awareness to run along my spine. No, he was not thoughtless at all. He had uttered exactly the notion that had come into his mind.

For my part, I had not foreseen any outcome of this nature. How would I?

And no, it was not like a rapier thrust at all, which would be clean and sharp and precise. This was more like a blast of hellfire. All my previous worries, trivial and domestic as they were now presented to me, all my confidence in my ability to cloak my thoughts in careful restraint, paled into insignificance beside the inherent danger in those chosen words, cast at my feet like a handful of baleful gems.

Cast there by John Plantagenet, royal prince, Duke of Lancaster.

My audience with the Duke, until this verbal cataclysm, had been much as I expected, as I had hoped. He welcomed me with all his customary grace. Had we not been acquainted for many years, since I had been raised from my days as a very youthful Katherine de Roet in the household of Queen Philippa, his lady mother? Our paths had crossed; we had shared meals and festivities. I had been a member of the royal household, held in high regard and affection, both as a child and as damsel to the Duke’s wife, Duchess Blanche. I was assured that whatever the outcome of my plea, the Duke would put me at my ease.

I rose from that first deeply formal curtsy when he had entered his audience chamber. Eyes downcast, breath shallow with nerves—for however well regarded I might be, if he refused I did not know where I would apply for succour—I made my request. It was hard to ask for charity, however gracious and generous the reputation of the benefactor.

‘Lady Katherine.’

‘Yes, my lord. I am grateful.’

His soft boots, the edge, gold-embroidered and exquisitely dagged, of his thigh-length robe, appropriate for some court function in heavily figured damask, came within the range of my vision, and I glanced up, momentarily alerted by a rough timbre in his speaking my name. Nor was the Duke’s expression any more encouraging. His straight brows were level, hinting at a frown, his lips tight-pressed, causing my heart to flutter against my ribs. He was going to refuse me after all. There was no position for me here. By tomorrow I would be back on the road to the fasts of Lincolnshire with nothing to show for my long journey. He would tell me kindly, but he would refuse me.

But then, as he caught some anxiety in my expression, he was smiling.

‘Don’t look so anxious, Lady Katherine. You never used to. Did you think I would turn you from my door?’

The roughness was smoothed away as he touched my arm, a fleeting pressure. My heart’s flutter became a thud.

‘Thank you, my lord,’ I murmured.

‘I cannot express my sadness for your husband’s death.’

‘Thank you, my lord,’ I repeated.

There was nothing else for me to say that would not overwhelm me with one difficult emotion or another. My husband was dead a mere two months, somewhere in the battlefields of Aquitaine.

‘I valued Sir Hugh’s services greatly.’ The Duke paused. ‘And yours have been inestimable. For you, Katherine,’ he lapsed into the more familiar, abandoning the title that had come with my marriage, ‘there will always be a position here.’ And then, with gentleness: ‘Your place in the Duchess Blanche’s household earned you great merit. You must come to us again.’

Relief spread through me, sweet as honey. I sighed imperceptibly. All the fears that had pinioned my mind in recent weeks so that I could not think, could not plan, could not envisage the future, fell away. I would no longer be dependent on the limited revenues from the Swynford estates at Kettlethorpe and Coleby. I would have money to spend on critical refurbishments. My children would lack for nothing.

‘Thank you, my lord,’ I said for the third time in as many minutes. I seemed to have lost the capacity to form any other response, and for a moment I was touched with a pale amusement. I had not been known for lack of conversation. ‘Forgive me,’ I said. ‘I cannot tell you how much that will mean to me.’

‘Is Kettlethorpe very bad?’ he asked. He knew my situation.

‘You have no idea, my lord.’

And with the relief I raised my eyes to his, to discover that he was watching me closely, so that I felt the blood rise to heat my cheeks, and my relief became overlaid with a layer of uncertainty. Perhaps he was waiting for a more effusive sign of my gratitude. After all, I had no claim on him, no tie of duty or blood. Some would say he had done quite enough for me and my family.

Could it be that he thought me unfit for the position I sought? Damsels in royal households were chosen for their elegance and beauty as much as for their practical skills, women worthy in appearance and demeanour to serve the lady. I had done my best. My dark robes were as fine as I could make them, with no remnant of Lincolnshire mud. As for my hands and face, all that could be seen in the all-enveloping shrouding, I had applied the contents of my stillroom with fervour to remedy the effect of Kettlethorpe’s demands. I did not think the Duke would judge me too harshly, knowing my circumstances. And yet his eye had the fierce focus of a raptor.