Полная версия:

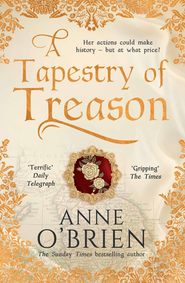

A Tapestry of Treason

Praise for

Anne O’Brien

‘O’Brien cleverly intertwines the personal and political in this enjoyable, gripping tale’

The Times

‘[A] fast-paced historical novel’

Good Housekeeping

‘Anne O’Brien has unearthed a gem of a subject’

Daily Telegraph

‘A gripping story of love, heartache and political intrigue’

Woman & Home

‘There are historical novels and then there are the works of Anne O’Brien – and this is another hit’

The Sun

‘The characters are larger than life…and the author a compulsive storyteller’

Sunday Express

‘This book has everything – royalty, scandal, fascinating historical politics’

Cosmopolitan

‘A gripping historical drama’

Bella

‘Historical fiction at its best’

Candis

ANNE O’BRIEN was born in the West Riding of Yorkshire. After gaining a BA Honours degree at Manchester University and a Master’s at Hull, she lived in the East Riding for many years as a teacher of history. After leaving teaching, Anne decided to turn to novel writing and give voice to the women in history who fascinated her the most. Today Anne lives in an eighteenth-century cottage in Herefordshire, an area full of inspiration for her work.

Visit Anne online at www.anneobrienbooks.com.

Find Anne on Facebook and follow her on Twitter: @anne_obrien

Also by

Anne O’Brien

VIRGIN WIDOW

DEVIL’S CONSORT

THE KING’S CONCUBINE

THE FORBIDDEN QUEEN

THE SCANDALOUS DUCHESS

THE KING’S SISTER

THE QUEEN’S CHOICE

THE SHADOW QUEEN

QUEEN OF THE NORTH

A Tapestry of Treason

Anne O’Brien

ONE PLACE. MANY STORIES

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Anne O’Brien 2019

Anne O’Brien asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © August 2019 ISBN: 978-0-008-22548-3

Note to Readers

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height

Change of background and font colours

Change of font

Change justification

Text to speech

Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN 9780008225476

With all my love, as always, to George, who immersed

himself in this tale of medieval politics and high drama.

A born Lancastrian, after reading of the

devious exploits of the House of York, he remains

a dyed-in-the-wool supporter of the red rose.

Cast of Characters

The Royal Court in 1399

King Richard II.

Queen Isabelle de Valois, Richard’s second wife.

The House of York

Edmund of Langley, Duke of York.

Isabella, Princess of Castile, now deceased, mother of the three York children:

- Edward of Norwich, Earl of Rutland, Duke of Aumale, later Duke of York.

- Constance of York, Lady Despenser, Countess of Gloucester.

- Richard (Dickon) of Conisbrough, later Earl of Cambridge.

The Despensers

Thomas, Lord Depsenser, Earl of Gloucester, husband of Constance, father of their 3 children:

- Richard.

- Elizabeth.

- Isabella.

Henry Despenser, Bishop of Norwich, in silent sympathy with the York and Despenser conspirators.

House of Lancaster

King Henry IV, son of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster.

Joanna of Navarre, Duchess of Brittany, second wife of King Henry.

The six royal children:

- Henry (Hal), Prince of Wales.

- Thomas.

- John.

- Humphrey.

- Blanche.

- Philippa.

John Beaufort, Earl of Somerset, half-brother to King Henry.

Henry Beaufort, Bishop of Winchester, half-brother to King Henry.

The Holland Family

John Holland, Earl of Huntington, Duke of Exeter.

Thomas Holland, 3rd Earl of Kent, John Holland’s nephew.

Joan, Duchess of York, second wife of Edmund of Langley, sister of Thomas and Edmund Holland.

Edmund Holland, 4th Earl of Kent, lover of Constance of York.

Madonna Lucia Visconti, an Italian lady with a large dowry, Countess of Kent, wife of Edmund Holland.

Alianore, daughter of Edmund Holland and Constance of York.

The Mortimers

Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March, a child in captivity in Windsor Castle.

Roger Mortimer, his younger brother, also in Windsor Castle.

The Percys

Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, a man of authority, ambition and conflicting loyalties.

Sir Henry Percy (Hotpsur), Northumberland’s son and heir.

Those to be found in aristocratic households

Friar John Depyng: King Richard II’s soothsayer.

Ralph Ramsey, one of King Henry IV’s esquires, rewarded for his loyalty.

William Flaxman, another Court minion in receipt of the King’s generosity

Richard Milton, agent of Constance in the Windsor plot.

A locksmith who paid for his conspiracy with his life.

Richard Maudeleyn, a clerk, who played the role of Richard II.

William Maidstone, Constance’s chivalric champion.

Sir John Pelham, a staunch supporter and counsellor of King Henry IV.

And in Wales

Owain Glyn Dwr, stirring rebellion in the west and claiming the title of Prince of Wales.

Contents

Cover

Praise

About the Author

Booklist

Title Page

Copyright

Note to Readers

Dedication

Cast of Characters

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Acknowledgements

What inspired me to write about Constance of York, Lady Despenser?

And Afterwards…

Travels with Constance of York, Lady Despenser

Excerpt

About the Publisher

Chapter One

February 1399: Westminster Palace

‘Entertain us, sir.’

Since my invitation caused Friar John Depyng to step aside in a display of speed impressive for so corpulent a figure, I smiled a brief show of teeth to soften my command. ‘If it please you, sir. We desire to take a glimpse into the future.’

Friar John, not won over to any degree, dared to scowl. ‘Divination is not for entertainment, my lady.’

Unperturbed, my brother Edward, forcefully large, grasped his elbow and drew him along with us. ‘You would not wish to refuse us. It would displease the King if your being disobliging happened, by chance, to come to his ear.’

The quality of Edward’s smile lit fear in the cleric’s eyes.

At my behest, we were borrowing Friar John, one of King Richard’s favourite preachers who had the gift of soothsaying, to while away an otherwise tedious hour after supper. Weary as we were of the minstrels and disguisers, my two brothers and my husband were not averse to humouring me, for here was a man famed for his prophecy. Was he not held in high regard by our cousin King Richard? Why not allow him to paint for us the future? I had said. All was in hand for the campaign against the treacherous Irish, waiting only on the King’s final command for embarkation. Why not enjoy our victory before it was even won?

We took occupation of a chill room in the Palace of Westminster, a room that looked as if it had once stored armaments but was now empty, save for stools and a crude slab of a table more fitting for some usage in King Richard’s kitchens.

‘Tell us what you see of the future,’ I demanded as soon as the door was closed, lifting the purse at my girdle so that it chinked with coin.

Yet still Friar John looked askance at me and my companions: my brothers Edward and Dickon, and Thomas my husband.

‘I will not,’ Friar John said. He lowered his voice. ‘It is dangerous.’ He glanced at the closed door, through which there was no immediate escape.

‘You will. I am Constance Despenser, Countess of Gloucester. I know that you will not refuse me.’

‘I know full well who you are, my lady.’

I pushed him gently to a stool, with a little weight on each shoulder to make him sit, which he did with a sigh while I leaned to whisper in his ear, the veils, attached with jewelled clasps to my silk chaplet, fluttering seductively. ‘We will reward you, of course.’

‘He’s naught but a cheap fortune teller.’ Thomas drew up a stool with one foot and sank onto it. ‘A charlatan who would tell any tale for a purse of gold.’

I did not even grace Thomas with a glance; to mock our captive priest would not warm him to our purpose. ‘The King goes to Ireland,’ I said. ‘Tell us of his good fortune. And ours.’

‘But not if you see my death,’ Edward grinned. ‘If you do, I expect you to lie about it.’

I passed a coin to Friar John who, suitably intimidated, took from a concealment in his sleeve two golden dice, placing them on the uneven surface of the table.

‘I like not dice prophecy,’ Thomas growled.

But Friar John, now in his métier and with the prospect of further coin, was confident. ‘It is what I have used to give the King a view of the coming days, my lord.’ Picking up the dice, with an expert turn of the wrist he threw them. They fell, rolled and halted to show a six and a six.

‘Is that good?’ Dickon asked, leaning his weight on the table so that it rocked on the uneven floor, until I pushed him away. He was Richard of Conisbrough when formality ruled, which was not often in this company. He was my younger brother by at least ten years.

‘Too good to be true.’ Thomas was scowling. ‘I recall the King had a pair of loaded dice, a gift when he was a child, so he could never lose. Until his friends refused to gamble with him. They were gold too.’

Friar John shook his head in denial, but more in arrogance. ‘There is no sleight of hand here, my lord. This is the most advantageous throw of all. The number six stands for our lord the King himself. It indicates his strength. This shows us that England is a paradise of royal power.’

‘Excellent!’ Edward said, arms folded across this chest. ‘Throw again.’

Friar John threw again. Each one of the die fell to reveal a single mark.

‘Is this dangerous?’ I asked. ‘Does this single mark then deny the royal power?’

‘Not so, my lady. This means unity. There is no threat against our King.’

‘None of this has any meaning!’ Thomas slouched on his stool, his chin on his folded hands, his solid brows meeting above a masterful nose, marring what might have been handsome if heavy features. ‘I swear it’s all a mockery. Don’t pay him.’

‘Again,’ I said. ‘One more time.’

Another throw of the dice to show a three and a three. Friar John beamed. ‘Excellent: the Trinity. And three is half of six. So to add them – three and three – means that the King remains secure. The campaign in Ireland will bring nothing but good.’

He collected the dice into the palm of his hand and made as if to secrete them once more into his sleeve, relief flitting across his face.

‘Not yet.’ I covered his hand with mine, for here, to my mind, was the true purpose of this venture. ‘Now throw the dice for us. What will our future hold?’

With a shrug, he threw again. A two and a three. The three was the first to be revealed, then the two to fall alongside. From Friar John there was a long intake of breath.

‘What is it?’ Edward demanded. ‘Don’t stop now…’

‘When two overcomes three, all is lost.’ The friar let the words fall from his tongue in a turbulence, with no attempt to hide his dismay. ‘When two overcomes three, disaster looms. Two reveals disunity. Disunity threatens the King. It threatens peace. It is necessary to unite behind the King to prevent so critical an attack on the peace of the realm. Sometimes it is necessary…’

He swallowed, his words at last faltering.

‘Sometimes what?’ I saw Edward’s fingers tighten into talons on our friar’s shoulder.

Friar John looked up into his face. ‘Sometimes it means that the King is unable to hold the realm in peace, my lord. It means that the lords of the realm must unite to choose a new King. One more fit for the task.’

‘But we don’t need a new King,’ I said. ‘We are content with the one we have. We will unite behind King Richard to…’

Thomas pushed himself to his feet with a clatter as the stool fell over. ‘Is that it? Is that all you see? It makes no sense.’

Needing the answer, reluctant that Thomas should break up the meeting, I grasped his arm. ‘Does seeing it make it so, sir? Is this what will occur? Disunity?’

‘No, my lady. Not necessarily…’

‘So it is all nonsense. As I said.’ Thomas, freeing himself, was already halfway to the door. ‘Pay him what you think he’s worth and let’s get out of here. It’s cold enough to freeze my balls.’

His crudity did not move me. I had seen the anxiety in Friar John’s eye. But before I could question him further: ‘Do you see me in the fall of the dice, Master Friar?’ Dickon asked.

‘I see no faces, no names, sir. That is not the role of the dice.’

‘Then where will you see me?’

Friar John was unwilling to be drawn by a question from a mere youth, not yet grown into his full height or his wits. ‘I cannot say. I might see it in a cup of wine, but there is none here to be had.’

He looked hopeful, but indeed there was nothing of comfort in the room, except the heavily chased silver vessel that Thomas had brought with him.

‘Then you can take yourself off, Master Dissembler. You’ll get no more from us, neither coin nor wine.’ Thomas held the door open for him.

But Friar John was staring at his hands, laid flat against the wood, fingers spread. His eyes stared as if transfixed by some thought that had lodged in his mind.

‘What is it, man?’ Edward asked.

The tip of the soothsayer’s tongue passed over his lips, and his voice fell as if chanting a psalm at Vespers, except that this was no religious comfort.

‘When a raven shall build in a stone lion’s mouth

On the church top beside the grey forest,

Then shall a King of England be drove from his crown

And return no more.’

A little beat of silence fell amongst us. Until Dickon laughed. ‘Do we have to kill every church-nesting raven, then, to save King Richard’s crown?’

Friar John blinked, looked horrified. ‘Did I say that? It is treason.’

‘No, it is not,’ I assured, hoping to get more from him before he fled. ‘Just a verse that came into your head from some old ballad from the north.’ I pushed Thomas’s abandoned cup in his direction.

Friar John drank the contents in two gulps, wiping his mouth with his hand, and when we made no move to prevent him, he left in a portly swirl of black robes. He forgot to take the dice with him.

‘Well! What do we make of all that?’ I asked. A sharp sense of disquiet had pervaded the room, as if we had stirred up something noxious.

‘I have no belief in such things,’ Edward replied. ‘Do we not make our own destiny?’

I could not be so dispassionate. ‘Cousin Richard has opened the doors of power for us. It will not be to our advantage for that power to be threatened.’

The Friar’s uneasy prediction was not what I had wanted to hear. We had been given a warning, enough to get under the skin like a winter itch.

‘Do you want my prophecy, sister?’ Edward was irresponsibly confident. ‘Without any need for golden dice, I say all will be well. I say we will return from Ireland with music and rejoicing. To whom will Richard apportion land in Ireland once it has fallen to him? I doubt we will be overlooked.’

‘And our authority will be greater than ever,’ Thomas concurred. ‘Let’s get out of here and find some good company.’

Edward punched Dickon on the shoulder. ‘And if we see a raven nesting near a grey forest, we set Dickon here to kill it.’

We laughed. Our tame soothsayer was indeed a mountebank, yet a discomfort remained with me beneath the laughter. Friar John had been disturbed. It had been no deliberately false reading. And to what purpose would it have been, to prophesy unrest and upheaval? There had been terror in his flight.

I scooped up the dice that the magician had left behind, before Edward could take possession. Out of cursory interest, I threw them, without skill. A three and then, a moment later as the second die fell, a two. The three overcome by the two. A warning? But to whom? I had no power to read the future.

I kept in step with Edward and Dickon as we strolled back to the Court festivities where the practised voices of the minstrels could be heard in enthusiastic harmony.

‘Did you learn what it was that you wished to learn?’ Edward asked.

I avoided his speculative glance. ‘I do not know that I wished to learn anything.’

‘Oh, I think you did. It was not merely a frivolous entertainment, was it? It was all your idea.’

I smiled, offering nothing, uncomfortable at his reading of my intention. I had learned nothing for my peace of mind but I would keep my own counsel, Edward being too keen to use information, even that given privately, to further his own ends. Not that there was anything for me to admit. As a family we were at the supreme apex of our powers. I merely wished to know that it would stay that way. Now I was unsure.

‘Give me the dice,’ Edward said, holding out his hand.

‘I will not,’ I replied, ‘since you have no belief in their efficacy.’

I would keep them. I abandoned my brothers when Edward lingered to demonstrate for Dickon a particular attack and feint with an imaginary sword, their breathless shouts and thud of feet gradually fading behind me.

Thomas had not waited for me.

Since there was nothing new in this, it barely caught my attention.

Early June 1399: Westminster Palace

At last the campaign was under way; King Richard was leaving for Ireland where he would land in Waterford and impose English rule on the recalcitrant tribes. It was an auspicious day, and as if Richard had summoned God’s blessing, jewels and armour and horse-harness glittered and gleamed in the full brightness of a cloudless sun. An accommodating breeze lifted the banners of the magnates who accompanied him so that the appliquéd motifs and heraldic goldwork rippled and danced. As did my heart, rejoicing at this creation of majesty on the move, as I stood on the waterfront to bid them farewell and Godspeed. Richard’s previous invasion, four years earlier, had not ended on a sanguine note, the settlement collapsing as soon as the English King’s back was turned. This time Richard’s foray would bring lasting glory to England.

‘I should be going with them.’ Dickon’s mood was not joyful.

‘Next time I expect you will.’

‘I am of an age to be there.’

He was of an age, at almost fifteen years, even if he had not yet attained the height and breadth of shoulder that made his brother so impressive a figure on the tilting ground or in a Court procession. One day he would be so; one day he might even achieve some coordination of thought and action. But even though that day was still far off, Dickon should have been a squire, riding in his lord’s entourage. Comparisons on all sides did nothing but intensify his dissatisfaction with life. Brother Edward had been knighted by King Richard at the ridiculously young age of four years. Yet here was Dickon, without patronage, without recognition, a mere observer in the courtly crowd. What could I say to make him feel better about his lot in life? There were things no one talked of in our family.

‘Enjoy this grand moment of celebration,’ was all I could offer. ‘You’ll get the chance to go to war soon enough.’

I understood the grinding need in him to make a mark on the world, to make a name for himself, even as it baffled me that men were so keen to go into battle and risk their lives.

‘Talk to the King, Con. Ask him to take me as one of his household. Or even Edward.’

I shook my head. It was too late. No one had in mind a younger son with shadows surrounding his birth. Instead I pinioned Dickon to my side. There was much to be enjoyed in the image of royal power set out before us, the walls of Westminster Palace providing a stately if austere backdrop. This would be the campaign to coat King Richard’s glory in even more layers of gold. The horses, commandeered from the monastic houses of England, glowed with well-burnished flesh. A dozen great lords paraded their own wealth and consequence. And then came a large household of knights, of bishops and chaplains, even foreign visitors who accompanied the King with dreams of victory.