скачать книгу бесплатно

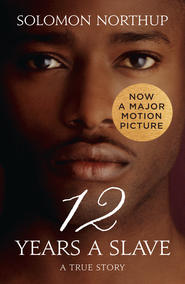

Twelve Years a Slave: A True Story

Solomon Northup

The shocking first-hand account of one man’s remarkable fight for freedom; now an award-winning motion picture.‘Why had I not died in my young years – before God had given me children to love and live for? What unhappiness and suffering and sorrow it would have prevented. I sighed for liberty; but the bondsman's chain was round me, and could not be shaken off.’1841: Solomon Northup is a successful violinist when he is kidnapped and sold into slavery. Taken from his family in New York State – with no hope of ever seeing them again – and forced to work on the cotton plantations in the Deep South, he spends the next twelve years in captivity until his eventual escape in 1853.First published in 1853, this extraordinary true story proved to be a powerful voice in the debate over slavery in the years leading up to the Civil War. It is a true-life testament of one man’s courage and conviction in the face of unfathomable injustice and brutality: its influence on the course of American history cannot be overstated.

Copyright (#ulink_704cd536-3005-55f3-8200-c81a6a8c5c52)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com)

This edition published in Great Britain in 2014

Life & Times section © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

Silvia Crompton asserts her moral rights as author of the Life & Times section

Classic Literature: Words and Phrases adapted from

Collins English Dictionary

Solomon Northup asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007580422

Ebook Edition © 2014 ISBN: 9780007580439

Version: 2015-05-18

History of Collins (#ulink_e5eea99d-b6f6-501d-a58e-a18a37bec694)

In 1819, millworker William Collins from Glasgow, Scotland, set up a company for printing and publishing pamphlets, sermons, hymn books, and prayer books. That company was Collins and was to mark the birth of HarperCollins Publishers as we know it today. The long tradition of Collins dictionary publishing can be traced back to the first dictionary William published in 1824, Greek and English Lexicon. Indeed, from 1840 onwards, he began to produce illustrated dictionaries and even obtained a licence to print and publish the Bible.

Soon after, William published the first Collins novel, Ready Reckoner; however, it was the time of the Long Depression, where harvests were poor, prices were high, potato crops had failed, and violence was erupting in Europe. As a result, many factories across the country were forced to close down and William chose to retire in 1846, partly due to the hardships he was facing.

Aged 30, William’s son, William II, took over the business. A keen humanitarian with a warm heart and a generous spirit, William II was truly “Victorian” in his outlook. He introduced new, up-to-date steam presses and published affordable editions of Shakespeare’s works and ThePilgrim’s Progress, making them available to the masses for the first time. A new demand for educational books meant that success came with the publication of travel books, scientific books, encyclopedias, and dictionaries. This demand to be educated led to the later publication of atlases, and Collins also held the monopoly on scripture writing at the time.

In the 1860s Collins began to expand and diversify and the idea of “books for the millions” was developed. Affordable editions of classical literature were published, and in 1903 Collins introduced 10 titles in their Collins Handy Illustrated Pocket Novels. These proved so popular that a few years later this had increased to an output of 50 volumes, selling nearly half a million in their year of publication. In the same year, The Everyman’s Library was also instituted, with the idea of publishing an affordable library of the most important classical works, biographies, religious and philosophical treatments, plays, poems, travel, and adventure. This series eclipsed all competition at the time, and the introduction of paperback books in the 1950s helped to open that market and marked a high point in the industry.

HarperCollins is and has always been a champion of the classics, and the current Collins Classics series follows in this tradition – publishing classical literature that is affordable and available to all. Beautifully packaged, highly collectible, and intended to be reread and enjoyed at every opportunity.

Life & Times (#ulink_92e01c75-e846-50f4-b39e-3335b6da610b)

12 Years a Slave is a tale of deception, violence and callous disregard for the human rights we now take for granted. It is a true story, and over a century and a half after it was published it still has the power to shock and shame. But perhaps the greatest tragedy of Solomon Northup’s memoir is that his experiences were not unique. He was simply one of the fortunate few who survived to tell the tale.

Until 1841 Solomon Northup could barely have imagined he might ever become the property of another man. He was a self-made success, a celebrated violinist, a homeowner and a family man – but a lapse in judgement, a misplaced trust, turned his American dream into a living nightmare. For twelve long years Solomon Northup was a slave in his own land.

The Last Years of the Slave Trade

When we think of slavery in the United States we tend to picture the barbarous trafficking of Africans across the Atlantic, but by Solomon Northup’s time this was no longer the case. In 1808, the year of Northup’s birth, the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves came into force. It was not until the end of the Civil War in 1865 that slavery within the United States was definitively abolished – and along with it the appalling physical, mental and sexual abuse endured at the hands of cruel masters – but the Act at least put an end to the forced transportation of Africans. It had been a long time coming: by 1808, the transatlantic slave trade had been in operation for almost 200 years, bringing an estimated 11 million Africans to the United States. Slaves may still have been seen as possessions to be bought and exploited by their masters, but it was becoming increasingly hard to deny that they too were Americans.

The War of Independence, or Revolutionary War (1775–83), played a decisive role in turning the tide against slavery. Perhaps inspired by their own newfound freedom from colonial subjugation, many American landowners freed their slaves, many of whom had fought alongside their masters against the British. Often this emancipation was granted in masters’ wills – as was the case with Solomon’s father, Mintus. Born into slavery in the United States, he ultimately found a sympathetic master in Captain Henry Northup of New York. In 1798, as stipulated in the captain’s will, Mintus became a freedman. In gratitude he took his former master’s family name.

A Country Divided

Solomon Northup was born in the relatively enlightened state of New York, which had abolished slavery in 1799, and he grew up as a free black American. His father had by this time built up a successful farming business and was able to provide an education, and music lessons, for his sons; Solomon, who in this memoir describes playing the violin as ‘the ruling passion of my youth’, ultimately became a professional musician. Mintus was even registered to vote.

Life was quite different in the Southern states, where lucrative sugar, cotton and tobacco plantations maintained a high demand for slaves throughout the first half of the nineteenth century. Even the nation’s capital, Washington DC, retained its thriving slave trade until 1862. And it was to Washington DC that Solomon Northup was lured in 1841 on the pretext of a well-paid fiddling contract. Northup knew the dangers of travelling into slave territory but he took the precaution of carrying his official identity papers with him. Thanks in large part to his privileged New York upbringing, he felt secure enough in his status as a free man to make the brief trip without even telling his wife, Anne, where he was going. He had not counted on the duplicitousness of his money-grabbing employers, who drugged him, stole his papers and sold him to a slave-catcher.

As late as 1850 new laws were being passed that made escape from slave states to free states almost impossible. If a black man in a free state was discovered to be a fugitive slave – or, as in the case of Solomon Northup, was simply suspected of being a fugitive slave – any person preventing his return to servitude was liable for a hefty fine. Slaves had no right to trial by jury and were not allowed to testify against whites. Northup came up against this unjust system himself when, even after the great success and widespread publicity of his tell-all memoir, he tried to sue those responsible for selling him into slavery and saw them all acquitted.

Literary Sensations

12 Years a Slave, published in 1853 – the year of Solomon Northup’s rescue – was not the first exposé written by a former slave. In 1825 fugitive slave William Grimes had published his story in order to raise the money to buy his way out of servitude, while perhaps the most famous slave memoir of them all, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, had appeared in 1845. But the timing of Northup’s revelations meant that his book became a crucial document for abolitionists in the last decade of American slavery.

One year earlier, in 1852, a white abolitionist author named Harriet Beecher Stowe had published Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a novel that exposed the harsh truth of life as a slave in the Southern states. It became an instant bestseller on both sides of the Atlantic and prompted further debate about slavery – so much so that it is anecdotally credited with instigating the Civil War of 1861–5. Northup’s first-hand account corroborated much of what Beecher Stowe had written in her novel, and was reviewed and written about in major newspapers including the New York Times. Over the next few years, as political divisions between North and South became ever more violent, Northup became a figurehead of the abolitionist movement and travelled around the free states and Canada giving lectures.

Solomon Northup disappeared from the public arena as suddenly as he had been thrust into it; there is little evidence of his whereabouts after 1857. He is not recorded in the census of 1860 and it is unlikely he lived to see the end of slavery in 1865. His memoir might likewise have vanished after it went out of print had historian Sue Eakin not happened upon the book in a bargain store in 1936 and recognised from her childhood a number of the families and plantations Northup mentions. After extensive research by Eakin and others, 12 Years a Slave was reissued in the 1960s and went on to become a bestseller once more. We may never know the end of Solomon Northup’s life story, but there is little doubt that his written legacy inspired his country’s greatest revolution, saving countless other black Americans from the same unspeakable fate.

Dedication (#ulink_18cb56c4-9365-5d5a-a5cf-f5ed2cc8f303)

To Harriet Beecher Stowe:

Whose name, throughout the World, is identified with the Great Reform: This narrative, affording another Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, is respectfully dedicated

Epigraph (#ulink_80d17ea8-a66d-5120-bf3d-323cfb7669af)

“It is a singular coincidence, that Solomon Northup was carried to a plantation in the red river country—that same region where the scene of Uncle Tom’s captivity was laid—and his account of the plantation, and the mode of life there, and some incidents which he describes, form a striking parallel to that history.”

—Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Such dupes are men to custom, and so prone

To reverence what is ancient, and can plead

A course of long observance for its use,

That even servitude, the worst of ills,

Because delivered down from sire to son

Is kept and guarded as a sacred thing!

But is it fit, or can it bear the shock

Of rational discussion, that a man

Compounded and made up like other men

Of elements tumultuous, in whom lust

And folly in as ample measure meet

As in the bosom of the slave he rules,

Should be a despot absolute, and boast

Himself the only freeman of his land?

—Cowper

CONTENTS

Cover (#uf8cae6da-b827-5c03-9c38-4385ad691774)

Title Page (#u4683d281-4fa1-5bf8-9672-e6cefa0c3290)

Copyright (#uc61298b1-a7c9-504b-812a-035b1934caa2)

History of Collins (#u84a65c78-894f-52b4-aae0-e104e566bf98)

Life & Times (#uf96504e8-5631-5c7a-94eb-68ea3797d33d)

Dedication (#u0ac2212f-b83b-5d86-ae11-e1cb4380758a)

Epigraph (#uf081aa03-c041-58c6-ad04-dedd0264190c)

Editor’s Preface (#ub34e0656-58c2-5df0-8205-781fc3eb5638)

Chapter 1 (#u66312da3-17c0-531b-a492-2106e5ac813a)

Chapter 2 (#u187862da-23ea-5320-9370-847bedaf7e31)

Chapter 3 (#u4e796479-9258-5f4b-903a-80292b056a02)

Chapter 4 (#ue486a049-7a48-5cab-9f77-b90e251decdd)

Chapter 5 (#u99e110eb-3985-5967-a66f-ae2a2651c2b7)

Chapter 6 (#u2d35b1ff-7491-50e2-8c6d-23d965dc9192)

Chapter 7 (#u888aed33-034e-5126-92fb-c92630cdb8ec)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Appendix A (#litres_trial_promo)

Appendix B (#litres_trial_promo)

Appendix C (#litres_trial_promo)

Classic Literature: Words and Phrases (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

EDITOR’S PREFACE (#ulink_f8cdb56c-a884-5df4-b8dc-225fec1ec470)

When the editor commenced the preparation of the following narrative, he did not suppose it would reach the size of this volume. In order, however, to present all the facts which have been communicated to him, it has seemed necessary to extend it to its present length.

Many of the statements contained in the following pages are corroborated by abundant evidence—others rest entirely upon Solomon’s assertion. That he has adhered strictly to the truth, the editor, at least, who has had an opportunity of detecting any contradiction or discrepancy in his statements, is well satisfied. He has invariably repeated the same story without deviating in the slightest particular, and has also carefully perused the manuscript, dictating an alteration wherever the most trivial inaccuracy has appeared.

It was Solomon’s fortune, during his captivity, to be owned by several masters. The treatment he received while at the ‘Pine Woods’ shows that among slaveholders there are men of humanity as well as of cruelty. Some of them are spoken of with emotions of gratitude—others in a spirit of bitterness. It is believed that the following account of his experience on Bayou Boeuf presents a correct picture of slavery, in all its lights and shadows, as it now exists in that locality. Unbiased, as he conceives, by any prepossessions or prejudices, the only object of the editor has been to give a faithful history of Solomon Northup’s life, as he received it from his lips.