Полная версия:

The Making of Poetry: Coleridge, the Wordsworths and Their Year of Marvels

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright © Adam Nicolson 2019

Cover image © In Xanadu (Island Studio)

All woodcuts photographed by Leigh Simpson

The author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008126476

Ebook Edition © June 2019 ISBN: 9780008126483

Version: 2019-05-20

Dedication

For Tom Hammick

On the island of his self

Epigraph

The making of verses, the making of works, occurs in the edges of your life, of your time, in your late nights or early mornings … And my words, the words for me, seem to have more nervous energy when they are touching territory that I know, that I live with … I can lay my hand on [a place] and know it. And the words, the words come alive and get a kind of personality when they are involved with it for me. The landscape is image. It’s almost an element to work with, as much as it is an object of admiration.

Seamus Heaney, speaking to Patrick Garland on Poets on Poetry, BBC 1, October 1973

Contents

1 Cover

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Dedication

5 Epigraph

6 Contents

7 1 Following

8 2 Meeting – June 1797

9 3 Searching June 1797

10 4 Settling – July 1797

11 5 Walking – July and August 1797

12 6 Informing – July and August 1797

13 7 Dreaming – September and October 1797

14 8 Voyaging – November 1797

15 9 Diverging – December 1797 and January 1798

16 10 Mooning – January and February 1798

17 11 Remembering – February 1798

18 12 Emerging – March 1798

19 13 Polarising – March 1798

20 14 Delighting – April, May and June 1798

21 15 Authoring – June 1798

22 16 Arriving – July 1798

23 17 Leaving – August and September 1798

24 Acknowledgements

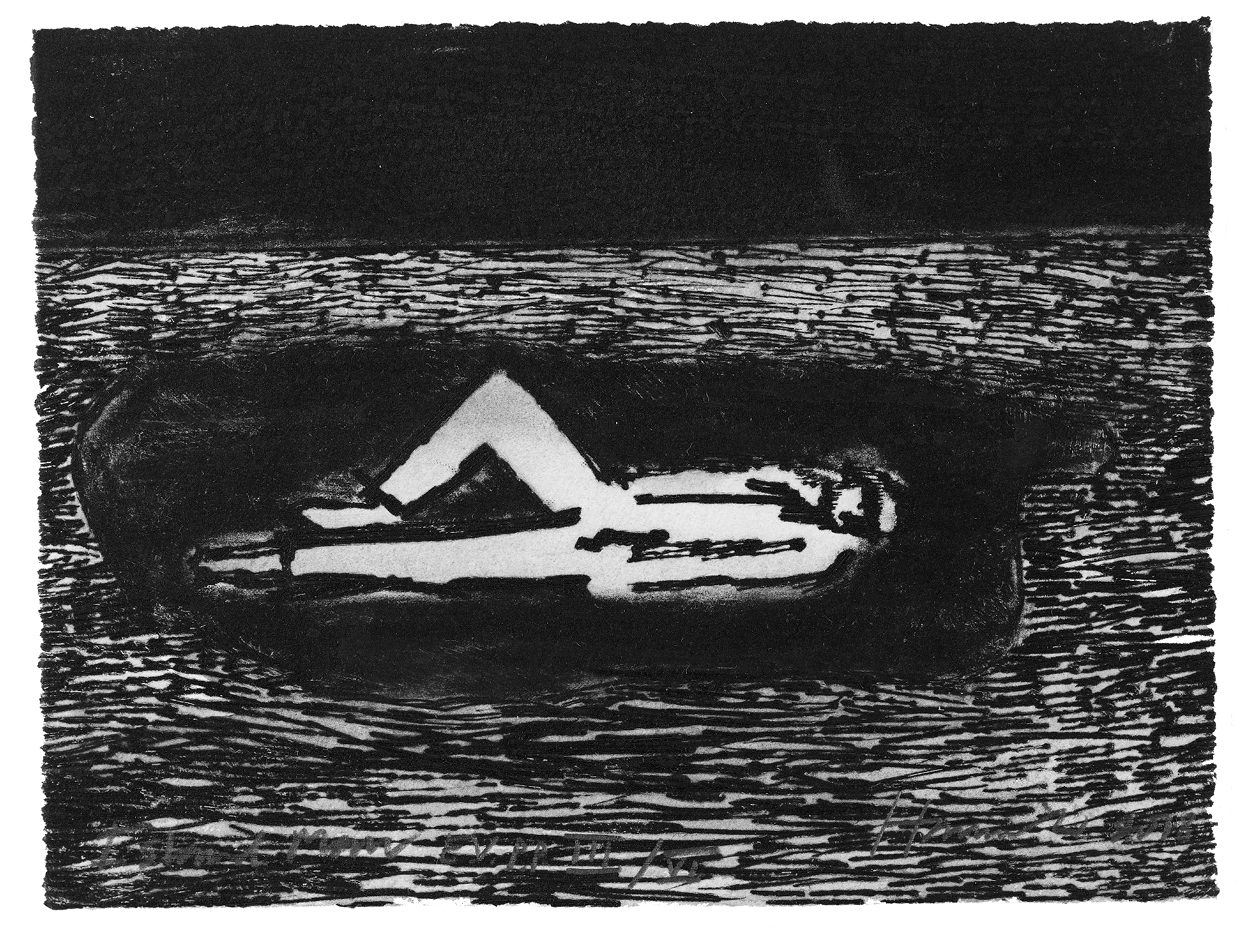

25 A Note on Tom Hammick’s Pictures

26 Notes

27 Bibliography

28 Index

29 Also by Adam Nicolson

30 About the Publisher

LandmarksCoverFrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pagesiiiivvix123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960616263646566676869707172737475767778798081828384858687888990919293949596979899100101102103104105106107108109110111112113114115116117118119120121122123124125126127128129130131132133134135136137138139140141142143144145146147148149150151152153154155156157158159160161162163164165166167168169170171172173174175176177178179180181182183184185186187188189190191192193194195196197198199200201202203204205206207208209210211212213214215216217218219220221222223224225226227228229230231232233234235236237238239240241242243244245246247248249250251252253254255256257258259260261262263264265266267268269270271272273274275276277278279280281282283284285286287288289290291292293294295296297298299300301302303304305306307308309310311312313314315316317318319320321322323324325326327328329330331332333334335337338339340341342343344345346347348349350351352353354355356357358359360361362363364365367368369370371372373374375376377381382383384385386387388389390ii

1

Following

The year, or slightly more than a year, from June 1797 until the early autumn of 1798, has a claim to being the most famous moment in the history of English poetry. In the course of it, two young men of genius, living for a while on the edge of the Quantock Hills in Somerset, began to find their way towards a new understanding of the world, of nature and of themselves.

These months have always been portrayed – by Wordsworth and Coleridge and by Wordsworth’s sister Dorothy as much as by anyone else – as a time of unbridled delight and wellbeing, of overabundant creativity, with a singularity of conviction and purpose from which extraordinary poetry emerged.

Certainly, what they wrote adds up to an astonishing catalogue: ‘This Lime Tree Bower My Prison’, ‘Kubla Khan’, The Ancient Mariner, ‘Christabel’, ‘Frost at Midnight’, ‘The Nightingale’, all Wordsworth’s strange and troubling poems in Lyrical Ballads, ‘The Idiot Boy’, ‘The Thorn’, the grandeur and beauty of ‘Tintern Abbey’, and, in his notebooks, the first suggestions of what would become passages in The Prelude.

The grip of this poetry is undeniable, but its origins are not in comfort or delight, or, at least until Wordsworth’s walk up the Wye valley in July 1798, any sense of arrival. The psychic motor of the year is something of the opposite: a time of adventure and perplexity, of Wordsworth and Coleridge both ricocheting away from the revolutionary politics of the 1790s in which both had been involved and both to different degrees disappointed. Wordsworth was unheard of, and Coleridge was still under attack in the conservative press. Both were in retreat: from cities; from politics; from gentlemanliness and propriety; from the expected; towards nature; and – in a way that makes this year foundational for modernity – towards the self, its roots, its forms of self-understanding, its fantasies, longings, dreads and ideals. For both, the Quantocks were a refuge-cum-laboratory, one in which every suggestion of an arrival was to be seen merely as a stepping stone.

The path was far from certain. One of Wordsworth’s criteria for pleasure in poetry was ‘the sense of difficulty overcome’, and that is a central theme of this year: their poetry was not a culmination or a summation, but had its life at the beginning of things, at a time of what Seamus Heaney called ‘historical crisis and personal dismay’, emergent, unsummoned, encountered in the midst of difficulty, arriving as unexpectedly as a figure on a night road, or a vision in mid-ocean, or the wisdom and understanding of a child.

It was not about powerful feelings recollected in tranquillity. Wordsworth’s famous and oracular definition would not come to him until more than two years after he had left Somerset. This was different, a poetry of approaches, journeys out and journeys in, leading to the gates of understanding but not yet over the threshold. Even now, 250 years after Wordsworth’s birth, it still carries a sense of discovery, drawing its vitality from awkwardness and discomfort, from a lack of definition and from the power that emanates from what is still only half-there.

This book explores the sources of this effusion. ‘I wish to keep my Reader in the company of flesh and blood,’ Wordsworth would write a couple of years later, and that has been my guiding principle too. The place in which these poets lived, the people they were, the people they were with, the lives they led, the conversations they had: how did all of that shape the words they wrote?

The received idea of these poets puts its focus on the immaterial, the floatingly high-minded. But here, in 1797, that is at least partly the opposite of the case. Thought for them, as the young Coleridge had written in excitement to his friend Robert Southey, was ‘corporeal’. He would later coin both ‘neuropathology’ and ‘psychosomatic’ as terms to describe aspects of this new interpresence of body and mind. The full life was not the enjoyment of a view, nor any kind of elegant gazing at a landscape, let alone sitting reading, but a kind of embodiment, plunging in, a full absorption in the encompassing world, providing the verbal life and ‘nervous energy’ that came from what Heaney would call ‘touching territory that I know’.

Here, then, was the invitation to which this book is an answer. If this was one of the great moments of poetic consciousness, it could best be understood as physical experience. By feeling it on the skin I could hope to know what had happened in the course of it. This was the subject that drew me: poetry-in-life, poetry-in-place, the body in the world as the instrument through which poetry comes into being.

The implication of that idea is that all currents must flow together. The way to approach this moment, its involutions and complexities, was to do, as far as possible, what the poets had done, to be in the Quantocks in all the moods and variations of the year at its different moments, to look for what happened and what emerged from what happened, to see how they were with each other, to feel the ebb and flow of their power relations and their affections. The timings and geography are closely known, often day by day, almost always week by week: what they were discussing, who they were meeting, how they were behaving, who their enemies and friends were, how poetry came from life-in-place.

Richard Holmes, the biographer of Shelley and Coleridge, has, unknown to him, long been my guide. When I was a young writer in the early 1980s he sent me a postcard out of the blue, encouraging me to keep going. So I have, and I think of this book as a tributary to the great Holmesian stream. Its method is his: to follow in the footsteps of the great, looking to gather the fragments they left on the path, much as Dorothy Wordsworth was seen by an old man as she was accompanying her brother on a walk in the Lake District, keeping ‘close behint him, and she picked up the bits as he let ’em fall, and tak ’em down, and put ’em on paper for him’.

So I went to live in the Quantocks. I started to imagine the poets’ lives. I bought the maps, I read what they had been reading, I immersed myself in their notebooks and the facsimiles of their rough drafts, starting to lower myself into the pool of their minds. Slowly I began to see these poets – and Dorothy Wordsworth should be included in that term – not as literary monuments but as living people, young, troubled, ambitious, dreaming of a vision of wholeness, knowing they had greatness in them but confronted again and again by the uncertain and contradictory nature of what they understood of the world, of each other and themselves.

It was a year focused on writing, on the search for forms of language that could, as Wordsworth later wrote of his own poetry, be ‘enduring and creative’, with ‘A power like one of Nature’s’. But it was not a sequence of solitudes. Coleridge’s profoundly lonely need for others guaranteed that they were not alone. It was a busy, social, talkative time. The two great poets were almost constantly surrounded by friends, acolytes, followers, patrons and relations; Wordsworth’s sister, Coleridge’s wife Sara, and the children they had with them. All provided the frame in which they lived. It is striking how often the poetry appears at the edges of that sociability, when the others have just gone, or their arrival is just expected, another of the margins at which this margin-entranced sensibility dwelt.

What emerges is something more nuanced than a straight-forward tale of miraculous productivity. Everywhere there are eddies in the stream: an interfolding of love and worry, ambition and doubt, a sense of possibility and of guilt, the patterns of human friendship oscillating between admiration and the recognition that the person you admire may not be entirely admirable, and may have the same hesitations about you.

The poets’ differences pulled and rubbed against each other. Their friendship, with its intermingling of affection and doubt, was a mutual shaping. Each became a source for the other, and each moulded himself in opposition to the other. It was intriguingly gendered. Coleridge could detect in himself elements of the female, but ‘Of all the men I ever knew,’ he wrote, ‘Wordsworth has the least femineity in his mind. He is all man. He is a man of whom it might have been said, – “It is good for him to be alone.”’

The driving and revolutionary force of this year was the recognition that poetry was not an aspect of civilisation but a challenge to it; not decorative but subversive, a pleasure beyond politeness. This was not the stuff of drawing rooms. Its purpose was to give a voice to the voiceless, whatever form that voicelessness might have taken: sometimes speaking for the sufferings of the unacknowledged poor; sometimes enshrining the quiet murmuring of a man alone; sometimes reaching for the life of the child in his ‘time of unrememberable being’, beyond the grasp of adult consciousness; sometimes roaming in the magnificent and strange disturbedness of Coleridge’s imagined worlds.

Wordsworth called poetry ‘the first and last of all knowledge’, using those words precisely: poetry comes both before and after everything that might be said. Its spirit and goal is to exfoliate consciousness, to rescue understanding from the noise and entropy of habit, to find richness and beauty in the hidden or neglected actualities. The strange, unlikely and unfashionable claim of this year stems from that recognition: poetry can remake assumptions, reconfigure the mind and change the world.

2

Meeting

June 1797

Early in June 1797, Coleridge was walking south through the lanes of Somerset and Dorset to visit Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy. I walked with him, the same lanes, the same air, absorbed in his frame of mind, my first embedding.

He was in the full flood of existence, bubbling and boiling with its possibilities and beauties, its conundrums and agonies, ensnared in ‘the quick-set hedge of embarrassment’ – money troubles always meant that ‘whichever way I turn a thorn runs into me’ – but ever alive to all that life could offer.

June in the west of England is frothing into colour and show: cow parsley and foxgloves, dark red campions mixed in with the alkanet and the nettles. The bees visiting each dangled foxglove hood in turn, as if turning in at a row of shops, pausing at each entrance, hesitating on the lip and then moving inside. The hawthorns are still clotted with blossom, the air double-creamy for yards around them. The elders are in bloom, their disk-like flower-heads held out into the roadway, dinner plates on the fingertips of an upturned hand. The first of the hay is being made in the paddocks and meadows, the swathes cut and laid across the buttercup hills. Bees in the brambles, honeysuckle in the hedges, the apple trees still just in blossom. Sprinkles of stitchwort. Every morning with a gloss on it, brushed and burnished.

The sociable time

His mind is full of starlings

A few years later Coleridge told a friend exactly how he felt when he found himself steaming along an inviting road like this, less a single man than a swarm of living things, animate nature itself, his mind as alive and mobile and endlessly self-reshaping as a concatenation of starlings oscillating and refiguring around his head. It was on the road like this, he told Tom Wedgwood, that

my spirit courses, drives, and eddies, like a Leaf in Autumn; a wild activity, of thoughts, imaginations, feelings, and impulses of motion, rises up from within me; a sort of bottom-wind, that blows to no point of the compass, comes from I know not whence, but agitates the whole of me; my whole being is filled with waves that roll and stumble, one this way, and one that way, like things that have no common master … Life seems to me then a universal spirit, that neither has, nor can have, an opposite. ‘God is everywhere,’ I have exclaimed, ‘and works everywhere, and where is there room for death?’

Coleridge, aged twenty-four, slightly fat – his friends called him ‘pursy’ – but strong, quite capable of forty miles between a summer dawn and dusk, or more than seventy miles over two days, had been on the road for three days, feeling ‘almost shillingless’ and chewing over his desperate need for cash. He had just come from seeing Joseph Cottle, his publisher in Bristol. Coleridge needed him for his money, and Cottle had offered ‘to buy an unlimited number of verses’. Cottle had ambitions as a poet himself: ‘The scatter’d cots/Sprinkling the vallies round, most gaily look./The very trees wave concord …’ It was an unequal relationship. Coleridge could flatter him when he needed to – ‘My dear Cottle’ – and just as easily dismiss him: ‘It is not impossible,’ he signed off one letter to this idealistic, helpful and generous bookseller-publisher, who did his best to promote the early careers of Coleridge, Southey and Wordsworth, ‘that in the course of two or three months I may see you.’

Now, though, Coleridge had shaken him out of his hair and the dust of Bristol from his feet, and was hungrily en route to the man he wanted to meet. He had given a sermon at the Unitarian chapel in Bridgwater, which ‘most of the better people in the town’ had attended, and the following day breakfasted with a much-adored minister in Taunton – ‘the more I see of that man, the more I love him’. The congregation in Bridgwater had admired his sermon, but was that right? Was admiration the reaction a sermon should evoke? He had ‘endeavoured to awaken a Zeal for Christianity by shewing the contemptibleness & evil of lukewarmness’, but even as those words came to him, he must have laughed. Lukewarmness was not a Coleridgean quality. He had a predilection for the extreme. Put him on a public platform and Coleridge would appear ‘like a comet or a meteor in our horizon’. He usually wrote his lectures or sermons in advance, but more often than not

against [my] better interests [I] was carried away with an ebullient Fancy, a flowing Utterance, a light and dancing Heart, & a disposition to catch fire by the very rapidity of my own motion, & to speak vehemently from mere verbal associations.

Now he was bowling down the summer lanes to meet Wordsworth. They had been corresponding for eighteen months, and Coleridge already admired him. He knew him as a poet, had met him in Bristol, and they had briefly stayed together in Somerset. He had quoted him in a poem of his own, and been quoted by Wordsworth in return. Coleridge already thought that Wordsworth was the greatest of men and ‘the best poet of the age’.

South Somerset and Dorset looked then, as they do now in midsummer, like southern comfort, with big, gentle, ten-mile views, the hills coming to well-coiffed peaks, rolled and tufted, bobbled with woods. But there was an illusion at work. These southern counties in the late 1790s were a pit of desperation, one of the poorest places in England. Anyone alive to political or human realities would be enraged by what they saw. Harvests had been bad. Long-term malnutrition kept the average height of the poor under five foot. The diet was ruinously thin: broth made of flour and onions and water for breakfast, meat maybe twice a week, otherwise the relentless repetition of bread and cheese. Bullock’s cheek was sometimes bought to flavour the broth. Potatoes were mashed with fat taken from that broth, and sometimes with salt alone.

In the evenings of early June, as the long days of the hay harvest made their demands on this underfed workforce, the labourers, watched by the diary-keeping gentry, were driven to the limits of exhaustion. William Holland, vicar of Over Stowey in Somerset, observed William Perrott, his aged parish clerk, always known as ‘Mr Amen’, struggling with the haymaking. He

looked like a hunted hare towards the end of the day, very stiff, could hardly move along, with his neck stretched out and his eyes hollowed into his head.

Mr Amen and two others had mown three and a half acres in the day, scything five tons of grass. Holland gave them ‘drink and some victuals, though the last not in the agreement’.

It was a world of brutal inequality. Your average high gentry family in the 1790s might be living off an income of £4,000 or more. There was scarcely any tax: Land Tax, Window Tax and Carriage Tax might add up to no more than £30 out of that £4,000. Local rates, to pay for the poorhouses in towns and villages, were levied, but came to only £10 extra per gentry family a year. Gifts were made to charity, to teach poor children or for the local infirmary, but the rich almost never gave away more than 1 per cent of their annual income.

Among the poor, general life expectancy was under forty. More than half of all babies born did not live beyond childhood. ‘Bad teeth, skin diseases, sores, bronchitis and rheumatism were rampant. Diagnosis was more by the eye than the touch.’ Most treatments were folk remedies in the form of leaves, roots, bark, spices and powders, and most were useless. There was no need for the poets to imagine or devise instances of human suffering. The wrongness of the social, economic and political system in England was apparent at every turn of every lane.

Coleridge, his person perhaps a little ‘slovenly’, as certain upright citizens had judged, with his stockings dirty and his hair uncombed, was walking through a country in crisis. New commercial capital coming into rural England meant that the landscape of small yeoman farms, which had been there for at least a thousand years, was being erased. What had been a class of independent farming families was now thrown back on work as servants, as piece workers in the woollen mills or as labourers on farms they had once called their own. By the late 1790s, Durweston near Blandford in Dorset, where there had been thirty or even forty smallholdings in 1775, was now concentrated into two large farms. The prevailing spirit among the dispossessed was unadulterated despair. Sir Frederic Morton Eden, the pioneering student of poverty in rural England, wrote of the Dorset poor in 1796 that the ex-yeoman families were ‘regardless of futurity’. It is a resonant phrase, which would not have been out of place in one of Wordsworth’s poems. Most of rural England was in a state of suspension, threatened by life without ambition or hope. The bonds of rural society had been broken, and this new class of the poor ‘spend their little wages as they receive them, without reserving a provision for old age’.

You need to shed any sense of Arcadian wellbeing. Britain was at war with France, press gangs were roaming the country to find men for the navy, informers were everywhere, and the Home Office files were bulging with letters from all corners, reporting on possible and known suspects. Prices were rising, and the country was full of maimed soldiers and desperate widows. Fences were often stolen for firewood. If you owned a cow and kept it in a field, you could expect it to have been milked by the hungry overnight. Hayricks by the road were regularly ‘plucked’ by the poor wanting to feed their own animals. Anyone growing peas would find them ‘swarming with the workhouse children’ in the weeks when the pods ripened. The dark, sunburned faces of the people were creased into premature old age. For meat they occasionally ate badgers, or the ‘Carrion Beef’ of a cow that had died in calving. The Reverend Holland, recording his parish visits in his journal, described how he called on a woman ‘in a most desperate way with a broken leg. She was glad to see me, and would crawl to the door.’ Otherwise, he sent his wife on the necessary visits. She