скачать книгу бесплатно

an imagined past. It is the turning

aside like Moses to the miracle

of the lit bush, to a brightness

that seemed as transitory as your youth

once, but is the eternity that awaits you.

(‘The Bright Field’, 1975)

Thomas, a parish priest in the Lleyn peninsula in Gwynedd, in the north-west corner of Wales, is playing a fugue on the words of both Exodus and the Gospels. The Authorised Version does indeed speak of Moses ‘turning aside’ to the burning bush; Christ, talking to the Apostles, describes the Kingdom of Heaven both as the field with the treasure in it and as the pearl of great price. Both, curiously perhaps to us who dissociate so firmly the religious from the financial, use the language of money and merchants. The conditions of paradise, in Christ’s own words, can be bought. If only estate agents had cottoned on to this! Sell all that you have, money for paradise, the pearl of great price, life is neither hurrying nor hankering: turn aside to the eternity that awaits you. Heaven is waiting, the paradise womb; only look for it and you will see the bush alight beside you. The brightness of youth can be once again to hand.

I look at myself then, nearly twenty years ago, and scarcely recognize the man I was: driven by a hunger for authenticity, for a place in the world that did not seem compromised but was somehow, in reality, almost heavenly. And I feel both nostalgia for that man – for the simplicity of his proposition – and utterly removed from him, as if he were some remote cousin, sharing a few common traits, and with something of a shared history, but with an attitude to the world that seems to know about almost nothing but himself. His need for happiness was so powerful that it erased nearly everything around him. It was as if he were walking through the world surrounded by a halo of need.

My own financial state was catastrophic. I was scarcely in a condition to work, or to look for work. A kind of vertigo gripped me whenever I tried to write anything. I was producing occasional pieces for the Sunday Times but they were ground out like dust from a mortar. All fluency had gone. I wrote a book of captions to photographs of beauty spots. I ghosted another on how to take landscape photographs. I researched the illustrations for a book on evolution. Apart from the islands in Scotland, which I would sell only if death were the other choice, I owned nothing. I had given my house and its contents to my first wife. I was paying her virtually everything I earned. At times I didn’t earn enough in the month to pay her what I had promised and Sarah, from her earnings as a doctor, made up the difference. Sarah, who had inherited a little money, at least owned her house in London, all save a small mortgage, and that was the lifeboat. That house in west London, with its three bedrooms and a sliver of a garden, would take us where we needed to go.

In that search for a place, nothing much was working. House after house was wrong, wrong in feeling, wrong in its situation, wrong in its price. The more the vision glowed, the less the places we saw came up to it. There were houses drowning in carpets and improvement, their souls erased. There were others in which the road was too near. Others too dour, many too far from Cambridge where my sons were living with their mother. Both Sarah and I felt an instinctive aversion to arable parts of England. We needed grass and wood, the Arcadian savannah, the lit bush, the field illuminated for a while. I knew that when we found the place it would say ‘I am here and I am yours. I am the place.’ It was a dark time.

Only at the edges, like jottings and little coloured drawings in the margins of a text, were there any points of light: the finding of wild daffodils one day in a Dorset wood; swimming one warm and languorous evening off Chesil Beach where the swell rolled in like a lion’s stretch and yawn, over and over, a long slow growling from the shingle; a weekend on the Lizard in a sea of thrift; dawn on the Helford River, anchored in a boat between the woods, where the night rain dropped off the outstretched leaves into water as still as oil. These were bright fields too, illuminations in their way.

Why should it be that beauty can for an instant make sense of a world in which nothing else does? I am not sure. It is something I believe in without knowing why. Maybe it is simply a recognition of pattern, a concordance between you and the world. Here in a chance beautiful thing is something given, neither engineered nor sought, neither curiously made nor elaborately framed, but dropping as a bead of meaning out of a meaningless sky. Its value, its weight, is in your own recognition of its beauty. There is something naturally there which you naturally recognize as good. The ability to see that beauty is a sign that the world is not an anarchy of violence and destruction. You belong to it and it belongs to you.

That was as near as I could come to understanding why I wanted to live and be in a place that seemed beautiful. The world around you in such a place would constantly touch you and speak to you. It would become an existence thick with understanding and that sense of crowding intelligibility might be almost social in its effect, as though you were actually joining the community of the natural. This, in my loneliness and guilt, became a kind of consolation too and I held on to it as a kind of flag of hope, a thought with which I could identify and salvage what remained of my self. There’s a sentence in one of Coleridge’s notebooks for 1807, when, also with a broken marriage and a career in ruins, he was staying on a farm in Somerset. A ragged peacock walked the yard: ‘The molting Peacock with only two of his long tail feathers remaining, & those sadly in tatters, yet proudly as ever spreading out his ruined fan in the Sun & Breeze.’ That was me with my faith in redemption by beauty, like the battle-shot colours of a regiment held up to the last.

I was at work in London – I say at work; I was sitting at my desk, looking at the screen, drinking a cup of coffee, considering from a dead mind the identity of the next possible word – and the phone rang. Sarah, in a coinbox, in a pub, breathless: ‘You must come. This is the place. I’m not sure. It might be. It’s a valley. An incredible valley. It’s like the Auvergne. It’s like an English Auvergne. Come on, sweetheart. You’ve got to have a look. It might be all right. It might be. I’m not sure. You’ve got to come though. Please come.’

She was in Sussex, having gone to look at a house that we both knew was too small – it was a converted observatory – and in the wrong place, on the top of a hill where nothing would ever grow, even if its views were to the Downs and the sea and a vast dome of observable sky. It was her second visit. She asked the man living there where he usually went for a walk. He mentioned a lane that dropped from this observatory down through the woods to the valley of a little river.

She had gone down the lane, curling between the hedgerows, under the branches of the overhanging trees. It was springtime and the anemones were starry in the wood. Primroses were tucked into the shade of the hedge banks. Catkins hung off the hazels over the lane. And then, at a corner, where to one side the trees opened out to a view down the valley, and from where the pleats of the valley sides folded in one after another into the blue distance of other woods and other farms, 4 or 5 miles away, there was a sign hanging out into the lane: ‘for sale’.

She took me back there the next day. Slowly the car went down the lane. The flowers in the verges, the sunlight in blobs and patches on the surface of the road. The knitted detail of this wood-and-field place. If anywhere were ever to look like nurture, privacy, withdrawal, sustenance, love, permanence and embeddedness, this was it. Sarah had found it.

Even then, at the first instinct-driven look, this felt as if it might be the place. Why was that? And how can the mind, in a series of fugitive impressions, never analysed and perhaps not consciously registered, make its mind up so fast?

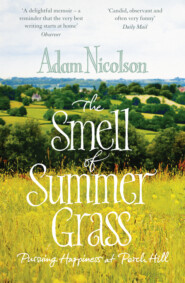

First, maybe, it was because Perch Hill was hidden. It was neither exposed to the world nor making a display to it. It was clearly living in its own nest of field and wood, a refuge which could find and supply richness from inside its own boundaries.

Second, I think, it reminded me a little of all the ingredients of the landscape I had known as a boy at Sissinghurst, 15 miles away in Kent: the coppice woods and the slightly rough pastures, the streams cutting down into the clay underbase, the woodland flora along their banks, that deep sensuous structure of light and shadow in a wooded country, where as you drop down a lane you are blinded first by the dazzle of the light and then by the depth of the shade, a flickering mobility in the world around you. Even at that subliminal level, here was somewhere that promised complexity and richness, secrets to be searched for and found.

And third, it was just the time of year, the first part of May, when England looks as if it has been newly made and the stitch-wort and campion are sparkling in the lane banks and not a single leaf on a single tree has yet gone leathery or dark or lost that bright, edible, salad greenness with which leaves first emerge into the world; and when even though the sun is shining the air is still cold and you can feel the fingers of the wind making its way between your shirt and your skin, a sensation somewhere on the boundary of uncomfortable and perfect, as if nearly perfect, as if courting perfection.

I can make this analysis only now. Twenty years ago, we were driving blind.

We turned the corner, saw the agent’s board, the sign on a little brick building saying ‘Perch Hill Farm’, and drove in. Almost everything about the place was as bad, in our eyes, as you could imagine it to be. The buildings were a horrible mixture of the improved and the wrecked: yards and yards of concrete; a plastic corrugated roof to the disintegrating barn; an oast-house whose upper storey had been removed during the war; a 1980s extension to the farmhouse, in the style of a garage attempting to look like a granary, paid for, I later learned, by selling off the milk quota. The farmhouse itself was dark and dingy downstairs. In most of the ground-floor rooms I was unable to stand up. Upstairs there was grey cheap carpet, gilded light fittings, down-lighters and pine-louvred cupboards. A 1940s brick cow shed had been enlarged with an extension made of telegraph poles and more corrugated sheeting. Three other sheds – for calves, logs and rubbish, I was told – lay scattered around the site looking as if they were waiting to be tidied up. Various bits of grass were carefully mown. There was a decorative fish pond the size of a dining-room table in front of the granary-sitting room. The truncated oast-house had become a cart shed but was now in use as an art gallery. There were places for customers to park.

None of this was quite what had been imagined. The smiles remained hanging on our lips. The buildings were raw-edged. Their arrangement was not quite what you would have hoped for, not quite a clustered yard, but a little strung out along the hill. The geese by the farm pond were angry. And a wind blew from the west. Turn aside, turn aside. I have seen the sun break through … The Bright Field murmurings were no more than faint.

Was it that time we walked around the farm or another? I don’t quite remember. We left again, slowly, back up the Dudwell lane, along others. We had lunch on the grass outside the Ash Tree at Ashburnham. I drank a pint of Harvey’s bitter and the bees hummed. We were not sure. We went back on other days, again and yet again, taking friends with us. They all thought not. The place was trammelled. Whatever it might once have had was now gone. We heard somehow that the actor and com edian John Wells had looked at the place and rejected it: too much to do. We too should look elsewhere. So we did: a large fruit farm near Canterbury, other places, Brown Oak Farm, Burned Oak Farm, Five Oaks Farm, which I occasionally pass in the car nowadays, now the focus of other lives, diverged from ours like atoms that collide for an instant and then bounce on to other paths, and never to connect with ours again.

The Perch Hill valley would not go away. It had taken up residence in my mind. I bought the largest-scale map of it that I could find and kept it on my desk. I read it at night before going to sleep, walking the dream place: the extraordinary absence of roads, the isolated farms down at the end of long tracks, the lobes of wood and fingers of meadow, the streams incised into creases in the contours, the enclosed world away from the brutalizing openness which I felt had reduced me to the condition I was now in. It is a hungry business, map-reading. It only feeds the appetite for the real. I had drawn in red biro a line around the fields and woods that went with Perch Hill Farm: 90 acres in all, draped across a shoulder of hill that ran down to the valley of the River Dudwell, and entirely surrounded by the remains of Dallington Forest. The red line around these acres made an island of significance. The more I looked at the map the more real my possession of those fields became, the more that red biro line described the island reality for which we were both longing. ‘Let’s go again,’ I said to Sarah. It would be the last time, the last throw, and then I would push this map away and the place would mean nothing to us and we could move on to other places and other obsessions.

It was a summer evening, four months after Sarah had first wandered down the lane. We went not to the house but to the fields. We had brought some bread and cheese with us. We walked around and the light was pouring honey on the woods. At the end we lay down in the big hay meadow known as the Way Field and looked across the valley to the net of hedgy woods and pastures beyond it, the terracotta tile-hung farmhouses pimpled among them, the air of unfiddled-with completeness, the haze of the hay. Owls hooted; two deer and their fawns came out of the wood into the bottom of the field to graze and look, graze and look in the pausing, anxious way they do. Graze and look, graze and look: it was what we had been doing for too long. We decided there and then: for the sort of money that could have bought you an extremely nice house in west London (double-fronted, courteous neighbours, Rosemary Vereyfied garden, a frieze of parked German cars, chocolate-coloured Labradors in pairs on red leashes) we would buy a cramped, dark old farmhouse, a collection of decrepit outbuildings and some fields that would never in a thousand years produce any income worth having. Was this wise? Yes. This was wise, the right thing to do, plumping for the lit bush. What else could money be for?

John Ventnor, the art dealer who owned the place, wanted what seemed like an outrageous amount for it: £480,000. We could afford, we thought, after the endless shuffling of portfolios, the sale of heirlooms and the accommodating of ‘certain grave reservations’ of financial advisers, no more than £375,000 and that was what we offered. Not enough. We offered £20,000 more. Not enough. What would be enough? He was prepared to countenance a 10 percent discount on the asking price: £432,000. Too much. What about £410,000? Not enough. And there it stuck for months.

We began again to look at other places but none was right. The vision in the evening field had its hooks in us. We waited, hoping that the delay would get to work on him, but it didn’t. It became clear that he shared the freehold with a stepdaughter who no longer lived there. She wanted him to sell up but he didn’t want to leave. He had no incentive to lower his price any further. We were in an impasse.

Sarah sold her house in London, our daughter Rosie was born and we all moved together into a rented basement flat of profound sterility and gloominess. I got a job on a newspaper and we borrowed money on that rather slender foundation. On winter evenings I drew plans and projections on my computer of how we might change Perch Hill, what kind of garden we might make, how we might take the land and farm it in a way that would be more generous towards it. The sliced-off oast-house became whole again on my night-time screen. I took to sitting in front of it with no other light in the room, a silvery brightness emanating from the dark, a possible future set against a present reality. Plantings and vistas criss-crossed the spaces between the buildings on my computer plans. One after another of these schemes I drew up, ever more elaborate, and they all shared the same title: ‘Arcadia for £432,000.’ Give everything you have.

One winter day I went down there again. I had never seen Perch Hill outside its springtime freshness or its hay-encompassed summer glory. This day was different. I was alone; Sarah remained with Rosie in London. A wind was cutting in from the east and for days southern England had remained below zero. All colour had drained out of the landscape. In the valley, the woods were black and the fields a silky grey as in my night-time visions of the place. The stones on the track into the farm were frozen and they made no sound as I drove over them. The geese were huddled in the lee of a bank, fingers of wind lifting the feathers on their backs. Even they couldn’t bring themselves to run out and attack me. Frost-filled gusts blew across the frozen pond. The buildings were besieged by cold.

I was there to persuade Ventnor that he should sell his farm to us for something less than the £432,000 at which he had stuck for so long. I had no real tools or levers with which to achieve this, only the suggestion that a lower price might be fair. Smilingly, over a cup of coffee, he refused. We sat first in the kitchen and then by the fire. He was polite but adamant. The oak logs burned slowly. To my own surprise, I felt no resentment. I sat there agreeing with every word he said. Why should he leave the embrace of this? Why should the poor man go out into the cold if he did not want to?

He left the room to see a man who had come to the door and as I sat there I began to be embraced by the warmth of the house. I felt it wrap its own fingers around me. If a house could speak, that was the day it spoke, the day I learned this wasn’t simply a place where we could come and impose our preconceptions. We couldn’t simply land the Bright Field fantasy here and take that as the reality in which we were now ensconced. There was some kind of dignity of place to be respected here. It had a self-sufficiency which went beyond the demands and obsessions of its current occupants. There was a pattern to it, a private rhythm, the deep, slow music to which it had been moving for the four or five centuries that people had lived in it. The two of us men sitting here now in front of the fire, what were we in the light of that? Transient parasites.

I left and we had failed to agree on price but in some other, quite unstated way, I had succumbed. The buildings might be a mishmash of what we wanted and what we didn’t. They might confront us with a list of things to do that stretched 10, 20 years into the future. The price that was required might be unreasonably high. But all of that was translated that frosty day, or perhaps started to be translated that frosty day, with the hot oak fire glowing as the only point of colour in a colourless world, into something quite different: a commitment to the place as it actually was, with all the wrinkles of its history and its habits, all its failings and imperfections, all its human muddle. Stop fussing, it said. Give yourself over to what seems good. Here – after catastrophe and culpable failure in my own life, after I had witnessed Sarah, now my wife, tending to me as I collapsed – was some kind of signpost towards coherence. Don’t look for the perfect; don’t be dissatisfied if the reality does not match the vision. Don’t insist on your own way. Feed yourself into patterns that others have made and draw your sustenance from them. Accept the other.

‘You mean pay him what he wants?’ Sarah asked that evening as I put this to her.

‘Yes,’ I said. And we did.

If a son or daughter of mine said to me nowadays that they were thinking of doing what we did then, selling everything, taking on deep debts, putting their families on the verge of penury for years to come and acquiring a place that needed more sorting out than they knew how to pay for, a rambling collection of half-coherent buildings and raggedy fields, I would say, ‘Are you sure? Are you sure you want to shackle yourself with all this? Do you know what it is you are so hungry for that this seems a price worth paying?’

Just now, faintly, as ghosts from the past, I remember people saying those things to us at the time and thinking, ‘Ah, so they don’t understand either. They haven’t understood what it is to be really and properly alive.’ And knowing for sure what that meant myself: that when faced with a steep slope or a rough sea, you should not quiver on the brink, or spend your life pacing up and down on the sand looking at the surf. You should plunge off down it or into it, trusting that when you arrive at the bottom or the far shore, you will know at least that the world’s terrors are not quite as terrifying as they sometimes seem.

Do I believe that now? Nelson told his captains that the boldest moves were the safest, but Nelson was happy to lose everyone and everything in pursuit of victory. I can’t forget the decades of debt and anxiety which lay ahead of us then, the years of work in trying to reduce the mountain of borrowings, article after article, the alarm clocks in the dark, the working late on into the night to try to balance the books. But would I now exchange the life we have had for one in which we had never taken that risk or made that step? No, not at all. I am as happy that Sarah and I married ourselves to Perch Hill as I am about the existence and beauty of my own children.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: