Полная версия:

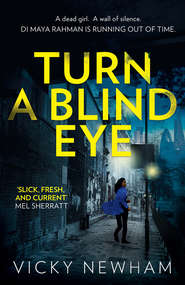

Turn a Blind Eye: A gripping and tense crime thriller with a brand new detective for 2018

Psychologist VICKY NEWHAM grew up in West Sussex and taught in East London for many years, before moving to Whitstable in Kent. She studied for an MA in Creative Writing at Kingston University. Turn a Blind Eye is her debut novel. She is currently working on the next book in the series.

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2018

Copyright © Vicky Newham 2018

Vicky Newham asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © April 2018 ISBN: 9780008240684

Version: 2018-09-17

PRAISE FOR TURN A BLIND EYE

‘A remarkable portrayal of a crime investigation in modern, multi-cultural Britain’

Paul Finch, Sunday Times bestselling author of Ashes to Ashes

‘A clever, gripping debut with a courageous DI at its heart’

BA Paris, author of Behind Closed Doors

‘Maya is wonderfully complex and human’

James Oswald, Sunday Times bestselling author of the Inspector Mclean series

‘A sensational debut; a current, timely police procedural featuring a DI like none you’ve ever seen. I loved this book!’

Karen Dionne, author of Home

‘Perfectly recreates the melting pot cultural atmosphere of East London; punchy and twisty. A terrific start to an important new series’

Vaseem Khan, author of the Baby Ganesh Detective Agency series

‘Assured and beautifully crafted, with a tempting array of clues to keep crime lovers glued to the pages’

Amanda Jennings, author of In Her Wake

‘DI Maya Rahman is the heroine I’ve waited a lifetime for’

Alex Caan, author of the Riley and Harris series

‘A fresh and enthralling read which smacks of authenticity. A different take on the usual, tired detective story, too. I loved it’

Lisa Hall, author of Between You and Me

‘Slick, fresh and current’

Mel Sherratt, author of The Girls Next Door

‘Stands out from the crowd. Filled with cryptic clues, this will keep you entertained throughout’

Caroline Mitchell, author of Silent Victim

For my father, who believed in kindness.

‘You may choose to look the other way but you can never say again that you did not know.’

—WILLIAM WILBERFORCE (1791)

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Epigraph

Kala Uddin Mosque, Sylhet, Bangladesh Thursday, 21 December 2017 – Maya

Wednesday, 3 January 2018 – Steve

Wednesday – Maya

Wednesday – Maya

Wednesday

Mile End High School, 1989 – Maya

Wednesday – Dan

Wednesday – Steve

Wednesday – Maya

Wednesday – Steve

Wednesday – Maya

Wednesday – Steve

Wednesday – Dan

Wednesday – Steve

Brick Lane, 1990 – Maya

Wednesday – Maya

Wednesday – Dan

Thursday – Maya

Thursday – Steve

Thursday – Maya

Thursday – Dan

Thursday – Maya

Thursday – Steve

Mile End High School, 1995 – Maya

Thursday – Maya

Thursday – Maya

Thursday – Maya

Thursday – Maya

Limehouse Police Station, 2005 – Maya

Thursday – Maya

Thursday – Maya

Thursday – Maya

Thursday – Dan

Thursday

Thursday – Maya

Thursday – Dan

Thursday – Maya

Mile End High School, 1991 – Maya

Friday – Maya

Friday – Steve

Friday – Steve

Friday – Maya

Friday – Maya

Friday – Steve

Friday – Maya

Friday – Maya

Friday – Steve

Friday – Maya

Friday – Steve

Saturday – Maya

Saturday – Dan

Saturday – Maya

Saturday – Maya

Sunday – Maya

Monday – Steve

Monday – Steve

Monday – Maya

Monday – Steve

Monday – Maya

Monday – Maya

Monday – Maya

Monday – Maya

Tuesday

Tuesday – Steve

Tuesday – Maya

Tuesday

Tuesday – Maya

Tuesday – Maya

Tuesday – Maya

Tuesday – Maya

Tuesday – Maya

Tuesday – Maya

Tuesday – Maya

Tuesday – Maya

Tuesday – Steve

Tuesday – Maya

Tuesday

Tuesday – Steve

Tuesday – Maya

Tuesday – Maya

Wednesday – Maya

Acknowledgements

Extract

Friday 5th April, 2019, Brick Lane, East London – Rosa

Q&A with Vicky Newham

About the Publisher

Kala Uddin Mosque, Sylhet, Bangladesh Thursday, 21 December 2017 – Maya

No amount of crime scenes and post-mortems could have prepared me for seeing my brother’s charred remains, wrapped in a shroud in the mosque prayer room. Out of the casket, and on a trolley, his contorted limbs poked at the white cloth like twigs in a cotton bag.

Since receiving the news of Sabbir’s death, I’d teetered on the water’s edge of grief. Imprinted on my mind were images of him burning alive in his own body fat, skin peeling away from his flesh. I imagined the flames using his petrol-doused clothes as a wick. And here, now, beneath the camphor and perfumes of the washing rituals, undertones of burned flesh and bone lingered.

In the dim light, surrounded by Qur’an excerpts, it was as though the walls were leaning in. My legs buckled and I folded to the ground, knees smashing on the concrete beneath the prayer room carpet. Tears bled into my eyes, and my hijab fell forwards. All I wanted was to curl into a ball on the floor and stay there forever because my kind, sensitive brother was nothing more than a bag of bones and a handful of teeth.

Burned alive in his flat in Sylhet.

My sister was beside me now on the floor, kneeling. ‘Get up,’ Jasmina muttered in my ear. ‘Remember what the imam said.’ She slotted her arm through mine. Hauled me to my feet and turned me to face the mihrab for prayers.

‘In the name of Allah and in the faith of the Messenger of Allah,’ said the imam.

His words rang out like bells from a far-off village.

In front of us, his back filled my view. I had a sudden image of standing behind white robes at the hospital in London twenty years ago when thugs beat Sabbir into a coma. Hadn’t that started it all? Sent him scuttling back to Bangladesh?

I scanned the room for an anchor. Took in the bulging bookcases, and the carved wooden screen which separated my sister and me from the four local men who’d carried in the casket. It was the medicinal smell of camphor that returned me to familiarity: when we were children, and had a cold, Mum would put a few drops on our pillow. Yet, despite the memories, Bangladesh hadn’t been my home for over thirty years.

The imam was asking for Sabbir to be forgiven and I felt the storm of anger swell.

‘Sssh,’ Jasmina hissed into my hair. ‘Maya. Look at me.’ She straightened my hijab and pinned it back in place. Licked her thumb and dabbed at my tear-streaked face.

But he hasn’t done anything wrong, I wanted to yell.

Five minutes later, and despite the humidity, it was a relief to be in the open air of the cemetery. How tiny the grave looked for my big brother.

The imam’s face was tight, and his cheek twitched with the misgivings he’d relayed to us over the phone. It will mean a woman positioning the bones in the grave, he’d said.

I removed my shoes and clambered down the rope ladder into the pit. The sweet smell of freshly dug soil filled my nostrils. It squished, soft and yielding beneath my toes, cold on my skin.

From above, Jasmina passed me Sabbir’s shrouded remains.

The imam’s cough was urgent.

I’d forgotten the dedication.

‘In the name of . . .’ I couldn’t say it.

He took over. ‘In the name of Allah, and by the way of the Messenger Allah . . .’

I carefully positioned my brother’s bones on the soil.

Femur.

Pelvis.

Laid his skull on its right cheek to face Mecca, the way the imam had shown me.

Then, in my periphery, something small scampered across the mud, brushing my foot. The scream was out of my mouth before I could muffle it and I hurled myself at the ladder. A man appeared at the graveside. In one swoop he raised a spade and sliced it down into the pit, on top of the animal and inches from my feet. Spats of fresh blood speckled the white shroud and my bare toes.

The imam raised his hands to either side of his head. ‘Allahu Akbar,’ he chanted. Then recited quietly, ‘You alone we worship. Send blessings to Mohammed.’

I imagined Sabbir’s clothes pulling more and more of his body fat into the orange, red and yellow flames as he burned alive.

‘Allahu Akbar. Forgive him. Pardon him. Cleanse him of his transgressions and take him to Paradise.’

His muscles drying out and contracting, teasing his limbs into greasy, branch-like contortions.

The imam gave the signal for the wooden planks to be placed on top of the shroud. Then the soil.

Beside the grave now, I pushed damp feet into my shoes. Took out the poem and, with Jasmina’s arm round my waist, read it aloud. Sabbir’s favourite: about the boy who waits for his preoccupied father to come and give him a hug before bed.

As the words of the poem echoed through me, I felt my brother’s suffering as though it were my own. I saw, more clearly than ever, how kind Sabbir had always been to others and how events over the years had eroded his faith that the unkindness that others had shown him would stop.

I closed the paperback and held it between my palms.

Dignified sorrow, the teachings stipulated.

And three days to grieve.

Yet Sabbir had endured a lifetime of anguish and was gone forever.

Wednesday, 3 January 2018 – Steve

Steve sat back in the plastic chair, squashed between two colleagues. Today was the start of the spring term at Mile End High School and he’d managed to turn up for the first day of his new job with a hangover.

‘Good morning, everyone. Welcome back.’ Linda Gibson, the petite head teacher, stood at the rostrum and surveyed the hall with an infectious grin. Her blue eyes danced with energy. ‘First of all, apologies for the lack of heating. I believe the engineers are fixing the boiler as I speak.’ She raised crossed fingers. ‘They’ve promised to perform miracles so we can all get warm and have lunch.’

Laughter ricocheted round the hall where the hundred-strong staff sat in coats and scarves, the room colder than the chilled aisles at the supermarket.

‘I hope you all had a lovely holiday,’ she continued. ‘I’m delighted to share good news: Amir Hussain, the year ten boy who was stabbed on Christmas Eve, is out of intensive care and doing well. In the sixth form, offers of university places have begun to trickle in.’ She paused. ‘Two final updates. Kevin Hall sadly had a stroke on Boxing Day, and Talcott Lawrence will step in as chair of governors until the end of term. Lastly, OFSTED notification could arrive any day.’

Nervous chatter skittered round the room.

‘There’s no cause for concern.’ Linda quickly raised her hand to reassure. ‘The inspectors will quickly see what a brilliant school we are.’ She gestured to the awards that hung proudly on the walls of the school hall.

Linda’s words floated over Steve’s head. All he’d been able to think about since arriving at the school that morning was when he’d be able to get to a shop for some Nurofen – but, despite his befuddled mental state, optimism began to tickle at him for the first time in months. After his last school in sleepy Sussex, he’d longed to escape mud and meadows and return to the vibrancy of East London, where he’d grown up. Hearing Linda speak, he felt sure he’d made the right decision – even though his head was swimming with information and everyone’s names were a blur. What an idiot he’d been to start drinking last night. After the long flight home from New York, the plan had been to have an early night. Why the hell hadn’t he stuck to it? To add to his regrets this morning, he’d read through his drunken texts to Lucy while he waited for the bus and cringed. What a twat. Hadn’t he promised himself he wouldn’t plead?

Linda was still talking. ‘We were all devastated by the suicide of Haniya Patel last term, and her parents have asked me to convey their thanks for our support.’

Steve’s phone vibrated in his pocket. His heart leaped at the thought it might be Lucy replying – and then sank. That was never going to happen. He had to focus on getting through today without making a prat of himself. This job was the new start he needed.

‘It’s a tragedy we’re all still coming to terms with.’ Linda’s voice was solemn. ‘In your e-mail you’ll find details of her memorial ser—’

A loud click sounded and a cloak of darkness fell on the hall. Stunned, the room was silent for a second, followed by whispered questions and nervous speculation.

‘We seem to have hit another problem.’ Linda’s voice came from the front of the room. ‘Can I suggest we all reconvene to the staffroom? I’ll find the caretakers.’

*

An hour later, the staffroom resembled the late stages of a student party. Gaping pizza boxes lay empty on every horizontal surface, and the room honked of warm fat. The engineers had got the heating working again, and although the lights were back on, the power cut meant they’d had to order in pizzas for the whole staff.

Most people were still eating chocolate fudge cake when the assistant head, Shari Ahmed, stood up and tapped on her mug with a biro. ‘Sorry to disturb you, everyone. Could we have a volunteer to nip along and tell the head we’re waiting for her? She must’ve got held up with the caretakers.’

‘I’ll go.’ Steve’s hand shot up. Result. Senior managers delegated everything in schools, which usually pissed Steve off, but it was a chance to get some air. And hopefully a fag.

‘Thanks,’ said Shari.

From the main corridor, Steve made his way through the ante-room where the head’s secretary worked, and approached the door to Linda’s office. He knocked and stuck his ear to the opening. Couldn’t hear anything. He knocked again, pushed the door open and walked in. ‘Mrs Gibson? Are you there?’

The room was in complete darkness. After the brightly lit corridors, he couldn’t see a thing. Disorientated, he stumbled into the room, right hand groping ahead for the lights. The tips of his shoes, and his knee caps, butted against a hard vertical surface, propelling him forwards. Arms flailing, he fell, landing on his front on something soft and warm and—

His senses exploded.

Hair was in his mouth and on his tongue. In the black of the room, the smell of human skin filled his nostrils, and he could taste sweat and perfume and – ‘Christ.’ Adrenaline spiked into his system as he realised it was a person underneath him. His limbs struck out like someone having a seizure, wriggling and writhing. With a push from his legs, he raised his trunk but his arms struggled on the shifting mass beneath him. Soft skin brushed his cheek. Hair forced its way from his tongue into his throat. Instantly his bile-filled guts retched, and his pizza shot over whoever was beneath him. ‘Oh my God.’ It was a low moan. Propelled by revulsion, his hands scrabbled, finally gained a hold and he heaved his core weight upwards and back onto his feet. Straightened his knees and stood up. His head was spinning.

Whoever it was, they were still warm. And if they weren’t dead, every second was critical.

Eyes adapting to the darkness, he made out the door nearby and lurched over, drunk with alarm. One hand landed on the architrave while the other grappled for the lights. Nothing that side. Ah. He flicked the switch.

Squinting in the brightness, he absorbed the scene.

The curtains were shut. An upturned chair. The desk surface was clear and objects littered the carpet. And on her back, on a deep sofa near the door, lay Linda. Her wrists were bound with cloth, and were resting on her belly. Hair – the tangle he’d had in his mouth – lay like a bird’s nest over her forehead. Steve’s vomit speckled the cream skin of her face and gathered at the nape of her neck. Hold on. Were those marks round her chin or was it the light?

And her eyes . . .

What the hell should he do? He knew nothing about first aid. And schools were sticklers for procedures. He’d have to get Shari.

Steve stumbled through the door into the office and corridor, aware every second counted. He traced his steps back to the staffroom, careering round corners. Relief swept over him when he saw the room was just as he’d left it: pizza boxes and people.

Shari frowned when she saw Steve arrive back alone. She scuttled over to meet him at the door, adjusting the hijab round her flushed face as she moved. ‘Is everything . . .? Where’s Mrs Gibson?’

‘Could I have a word?’ Steve’s stomach was churning. He slid to the floor. No. I can’t throw up here. Not in front of everyone.

Slow breaths.

‘Yes. Of course.’ The older woman’s eyes narrowed with concern. She stood over Steve. Waiting.

‘It’s Mrs Gibson . . . I think she’s dead.’

Wednesday – Maya

The sound wrenched me awake. Trilling. Vibrating. Sylhet dreamscape was still swirling, and I had no idea where the noise was coming from. Fumbling for the alarm clock on the bedside table, my clumsy fingers sent objects crashing to the floor.

It was my mobile, not the clock. Why the hell hadn’t I switched it off?

‘Rahman.’ I cleared my throat. My body clock was still adjusting after Sabbir’s funeral and a day spent travelling.

A woman’s voice came through. ‘This is Suzie James from the Stepney Gazette. There’s been a suspicious death at Mile End High School and —’

‘A what?’ Suzie’s name was all too familiar. ‘How did you get my number?’

‘A suspicious death. It’s your old secondary school so I was hoping for a quote for the paper.’

The groan was out before I could catch it. ‘Who’s dead?’ I was wide awake now, synapses firing. I groped for the light on the bedside table.

‘It’s the head, Linda Gibson. Would you like to comment?’

‘No, I wouldn’t. This is the first I’ve heard of it.’

‘The thing is, I’ve got parents asking questions and —’

‘Okay, okay.’ I flung the duvet back and swung my legs over the edge of the bed. A whoosh of cold air hit my skin. Suzie James would always write something, regardless of how much she knew, so it was better to give her the facts. ‘Give me twenty minutes. I’ll meet you at the school and find out what’s going on.’

‘Ta.’ The line went down.

I threw the phone down on my bed and moved across the room to open the blinds. From the window of my flat, the canal was serene and green in the afternoon light and ducks weaved through the shimmering water. A jogger shuffled along the tow path from Johnson’s Lock. In the distance, the skyscrapers of Canary Wharf loomed against a thundery backdrop. I rested my forehead against the glass. What was I doing? I was on compassionate leave until tomorrow. Then I remembered the poem I’d read at Sabbir’s funeral; how much my brother had suffered. Wasn’t this why I did my job – to bring justice to people who should never have become victims? Nostalgia flooded through me as I recalled my first day at the school in year seven, and how the place quickly became my lifeline. Just as it would be now for other kids like me. There was no way I was going to let the school’s reputation nosedive. I had to find out what was going on.

Wednesday – Maya

On the main road, a few minutes later, the traffic was solid in both directions towards Bow. In front of me, a lorry, laden with scaffolding, clattered along behind a dirty red bus, while a shiny black cab sniffed its bumper. Ahead, at Mile End tube station, the carriageway snaked under the Green Bridge, from which school pupil Haniya Patel had hanged herself in the small hours four weeks earlier. Driving under it, I held my breath.

Soon I was off the main drag, and the grey fell away. Yellow brick houses lined the streets in elegant terraces, holly wreaths on their ornate door knockers. In the afternoon light, Christmas fairy lights twinkled in bay windows. They were so pretty. I’d left for Sabbir’s funeral in such a hurry I’d not put my own lights up, and it was pointless when I got back. Outside the Morgan Arms, the beautiful red brick pub, smokers and vapers huddled beside the window boxes of purple pansies, sharing the chilly air. Up ahead, flashing blue lights cut through the slate grey sky.

When I pulled up, uniformed officers were struggling to contain members of the public within the outer cordon. Family members scurried about, indiscriminately seeking information and reassurance from anyone who could give it; others stood in huddles, no less anguished, simply shell-shocked and immobilised. The outer cordon covered an enormous area, far bigger than I remembered the school being. Round me, engines droned and vehicle doors slammed.