скачать книгу бесплатно

When she came back she just lay on the mattress beside Grandmother, and they cried together for days. She turned her face away from me, and would not speak to me. I wondered if she would ever speak to me again.

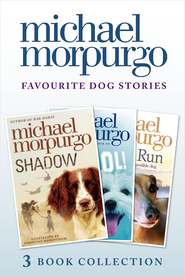

It wasn’t long after this that the dog first came to our cave – a dog just like your dog in that photo you showed me.

But when I saw her that first evening, she was thin and dirty and covered in sores. I was just crouching over the fire warming myself, when I looked up and saw her sitting there, staring at me. She wasn’t like any dog I had seen before – small, with short legs and long ears, and nut-brown eyes.

I shouted at her to go away – you understand, we do not have dogs inside our homes in Afghanistan. Dogs have to live outside with the other animals. Of course, I have lived here a long time now, and I know that in England it is different. Some people here like dogs better than they like children. Actually, I think if I was a dog, they would not shut me up in here like this.

So anyway, I threw a stone at this dog to shoo her away. But she stayed right where she was, and would not move. She just sat there.

I saw then that she was shivering. You could see her hipbones sticking out – she was that thin. She had sores all over her, and you could tell she was starving. So instead of throwing another stone at her, I threw her a piece of stale bread. She snapped it up at once, chewed on it, swallowed it, and then licked her lips, waiting for more.

I chucked her another piece. Then, before I knew it, she had come right into the cave, and was lying down there beside me, close to the fire, making herself at home, as if she belonged there. I noticed then that there was a wound on her leg, like she’d been in a dog-fight or something. She kept worrying at it, and licking it.

Mother and Grandmother were both fast asleep. I knew they’d chase the dog out as soon as they saw her there. But I liked her with me. I wanted her to stay. She had kind eyes, friendly eyes. I knew she wouldn’t hurt me. So I lay down and slept beside her.

Early the next morning, she followed me down to the stream when I went to fetch the water. She was limping badly all the way. She let me bathe her leg and clean her wound. Then I told her she had to go, and clapped my hands at her to try to drive her away. I knew that anyone seeing her might well throw stones at her – like I had after all – and I didn’t want that. But all the way back up the hill, she would not leave my side. Sure enough, as soon as we were spotted, a whole bunch of kids came running down the track and chased her off. They threw stones at her, and shouted at her, “Dirty dog, dirty foreign dog!”

I tried all I could to stop them, but they wouldn’t listen. I don’t blame them now. After all, she did look different, not like the kind of dog any of us might have seen before. She scampered off and disappeared. I thought that was the last I’d ever see of her.

But that evening she turned up again at the mouth of the cave. I discovered then that she liked tripe, however rotten it was. You know tripe? It’s a sort of meat, from the stomach lining of a cow – it was the only meat we could ever afford in Bamiyan. Anyway, there were a few rotten bits still left, so I threw her those.

But then later on, when the dog crept in to be by the fire again, Mother and Grandmother woke up and saw what was going on. They became very angry with me, saying all dogs were unclean, and that she shouldn’t be allowed in. So I picked her up and put her down just outside the cave, where she sat and watched us, until Mother and Grandmother had gone to bed. She seemed to know it was safe to come in then, because when I lay down, she was right there beside me again.

“You Must Come to England.”

Aman

For weeks and weeks that’s how it went on.

Somehow the dog just seemed to know that when I was alone, or when they were fast asleep, it was all right for her to come inside the cave. And she knew when to keep her distance too. She’d be sitting there in the mouth of the cave when I woke every morning, and she’d come with me down to the stream. She’d have a good long drink, and wait for me to bathe the wound in her leg. Then, so long as there was no one else about, she would come with me when I went off with the donkey to gather sticks for the fire.

But there were some days, particularly when my friends were around a lot, that I’d hardly see her at all, just an occasional glimpse of her in the distance, watching me. I’d miss her then, but it was good to know she was still around. And sooner or later every evening she’d be there again at the mouth of the cave, waiting for her food, waiting for Mother and Grandmother to fall asleep. Then in she’d come, and she’d lie down beside me, her face so close to the fire that I thought she’d burn her whiskers.

One morning, I woke up early and found the dog was not there. And then I saw why. Grandmother was already awake. She was sitting up on the mattress, with Mother still lying down beside her, and I could see Mother was upset, almost in tears. I thought they’d had another quarrel maybe, or that Mother’s back was hurting her again.

But I soon learned what this was all about. They had talked about it often enough before, about the idea of Mother and me leaving Bamiyan, and going to England on our own, without Grandmother. She was far too old to come with us, she said. Grandmother would sometimes read out Uncle Mir’s postcards from England. I had never even met Uncle Mir – he is Mother’s older brother – but I felt as if I had. I knew his story. He had left Bamiyan long before I was born.

Everyone in the caves knew about Uncle Mir, how he had gone off as a young man to find a job in Kabul, that he had met and married an English nurse, a girl called Mina, and then gone off with her to live in England. He had never come back, but he wrote often to Grandmother. Uncle Mir was her only son, so all his letters and postcards were very precious to her.

She was always taking them out and looking at them. They had been brought over to her from time to time by Uncle Mir’s friends when they were visiting from England, and she’d kept them hidden in her mattress with all her other precious things. She loved to show me the postcards, of red buses, or of red-coated soldiers marching, of bridges over the river in London. There was one that she read to us, over and over again. I remember almost every word of it. Whenever she read it, it started an argument.

“One day,” Grandmother would read out, “you must all come to England. You can live in our house. Mina and I have plenty of room for everyone. There is no war here, no fighting. My taxi business is good now. I have money I could send. I could help you to come.”

And Mother would always argue. “I don’t care about Mir and his postcards. And anyway, haven’t I told you and told you? I’m not going anywhere without you. When your legs are better, God willing, then maybe.”

“If you wait for my legs to get better, you will never go,” Grandmother would argue back. “I am your mother. But your father would say the same if he was still with us. I am only asking you to do what I say, because it is what he would say. I am old. I have had my time. I know this. I feel it inside me. These legs will never walk again like they did. You and Aman must go. There is nothing for you in the place except hunger and cold and danger. You know what will happen if you stay. You know the police will come again. Go to England, to Mir. You will be safe there. He will look after you. There you will be far from danger, far from the police. Listen to what Mir is telling us. There, the police will not put you in prison and beat you. There, you will not have to live in a cave like an animal.”

Mother often tried to interrupt her, and Grandmother hated that. One day, I remember, she became really angry, as angry as I had ever seen her.

“You should have some respect for your old mother,” she cried. “You expect Aman to do as you say, don’t you? Don’t you? Well, now you must do as I say. I tell you, I will be in God’s hands soon enough. I do not need you to stay. God will look after me, as he will look after you on your journey to England.”

She reached in under her dress, and brought out an envelope, which she emptied out on to the blanket beside her. I had never seen so much money in all my life. “Last week, Mir’s friend came again with another card, and this time with some money too, enough, he says, to get you out of Afghanistan, through Iran, and Turkey, and all the way to England. And on the outside of the envelope here, he has written the phone numbers of people he says you must contact, in Kabul, in Teheran, in Istanbul. They will help you. And you must take these too.”

She was taking off her necklace, pulling the rings from her fingers. “Take these, and I shall give you also all the jewels I have been keeping for you all this time. Sell them well in Kabul, and they will help to buy you your freedom. They will take you away from all this fear and ignorance. It is fear and ignorance that kills people in their hearts, that makes them cruel. Take Father’s donkey too. It’s what he would have wanted. You can sell him when you do not need him any more. Do not argue with me. Take them, take the envelope and the money, take the jewels, take my beloved grandson, and just go. And God willing, you will get to England safely.”

In the end, Grandmother managed to persuade Mother that we should at least speak to Uncle Mir on the phone. So the next time we went into town, to the market, we phoned him from the public phone. Mother let me talk to him when she had finished. In my ear, Uncle Mir sounded very close by, I remember that. He talked to me in a very friendly way, as if he had known me all my life. Best of all, he told me he supported Manchester United, and that was my team. And he had even seen Ryan Giggs, and my best hero too, David Beckham! He said he’d take me to a match, and that he’d let us stay with him and Mina as long as we needed to, until we could find a place of our own. After I talked to him, I was so excited. All I wanted to do was to go to England, go right away.

After the phone call Mother stopped to buy some flour in the market, and I walked on. When I turned round after a while, to see if she was coming, I saw one of the stallholders was shouting at her, waving his hands angrily. I thought it was an argument about money, that maybe she’d been short-changed. They were always doing that in the market.

But it wasn’t that.

She caught me up and hurried me away. I could see the fear in her eyes. “Don’t look round, Aman,” she said. “I know this man. He is Taliban. He is very dangerous.”

“Taliban?” I said. “Are they still here?” I thought the Taliban had been defeated long ago by the Americans, and driven into the mountains. I couldn’t understand what she was saying.

“The Taliban, they are still here, Aman,” she said, and she could not stop herself from crying now. “They are everywhere, in the police, in the army, like wolves in sheep’s clothing. Everyone knows who they are, and everyone is too frightened to speak. That man in the market, he was one of those who came to the cave and took your father away, and killed him.”

I turned around to look. I wanted to run back and tell him face to face he was a killer. I wanted to look him in the eye and accuse him. I wanted to show him I was not afraid. “Don’t look,” Mother said, dragging me on. “Don’t do anything, Aman, please. You’ll only make it worse.”

She waited till we were safely out of town before telling me more. “He was cheating me in the market,” she said, “and when I argued, he told me that if I do not leave the valley, he will tell his brother, and he will have me taken to prison again. And I know his brother only too well. He was the policeman who put me in prison before. He was the one who beat me, and tortured me. It wasn’t because of the apple you stole, Aman. It was so that I would not tell anyone about what his brother had done to your father, so that I would not say he was Taliban. What can I do? I cannot leave Grandmother. She cannot look after herself. What can I do?” I held her hand to try to comfort her, but she cried all the way home. I kept telling her it would be all right, that I would look after her.

That night I heard Mother and Grandmother whispering to each other in the cave, and crying together too. When they finally went to sleep, the dog crept into the cave and lay down beside me. I buried my face in her fur and held her tight. “It will be all right, won’t it?” I said to her.

But I knew it wasn’t going to be. I knew something terrible was going to happen. I could feel it.

“Walk Tall, Aman.”

Aman

Early the next day the police came to the cave. Mother had gone down to the stream for water, so I was there alone with Grandmother when they came, three of them. The stallholder from the market was with them. They said they had come to search the place.

When Grandmother struggled to her feet and tried to stop them, they pushed her to the ground. Then they turned on me and started to beat me and kick me. That was when I saw the dog come bounding into the cave. She didn’t hesitate. She leaped up at them, barking and snarling. But they lashed out at her with their feet and their sticks and drove her out.

After that they seemed to forget about me, and just broke everything they could in the cave, kicked our things all over the place, stamped on our cooking pot, and one of them peed on the mattress before they left.

I didn’t realise at first how badly Grandmother had been hurt, not till I rolled her over on to her back. Her eyes were closed. She was unconscious. She must have hit her head when she fell. There was a great cut across her forehead. I tried to wash the blood away, kept trying to wake her. But the blood kept coming, and she wouldn’t open her eyes.

When Mother came back some time later, she did all she could to revive her, but it was no good. Grandmother died that evening. Sometimes I think she died because she just didn’t want to wake up, because she knew it was the only way to make Mother and me leave, the only way to save us. So maybe Grandmother won her argument with Mother, in her own way, the only way she could.

We left Bamiyan the next day, the day Grandmother was buried. We did as Grandmother had told us. We took Father’s donkey with us, to carry the few belongings we had, the cooking things, the blankets and the mattress, with Grandmother’s jewels and Uncle Mir’s money hidden inside it. We took some bread and apples with us, gifts from our friends for the journey, and walked out of the valley. I tried not to look back, but I did. I could not help myself.

Because of everything that had happened, I think, I had almost forgotten about the dog, which hardly seems fair when I think about it. After all, only the day before, she had tried to save my life in the cave. Anyway, she just appeared, suddenly, from out of nowhere. She was just there, walking alongside us for a while, then running on ahead, as if she was leading us, as if she knew where she was going. Every now and then, she would stop, and start sniffing at the ground busily, then turn to look back at us. I wasn’t sure whether it was to check we were coming, or to tell us everything was all right, that this was the road to Kabul, that all we had to do was follow her.

Mother and I took it in turns to ride up on the donkey. We did not talk much. We were both too sad, about Grandmother’s death, about leaving, and too tired as well. But to begin with the journey went well enough. We had plenty of food and water to keep us going. The donkey kept plodding on, and the dog stayed with us, still going on ahead of us, nose to the ground, tail wagging wildly.

Mother said it was going to take us many days of walking to reach Kabul, but we managed to find shelter somewhere each night. People were kind to us and hospitable. The country people in Afghanistan haven’t much, but what they have, they share.

At the end of each day’s walk, we were always tired out. I wasn’t exactly happy. I couldn’t be. But I was excited. I knew I was setting out on the biggest adventure of my life. I was going to see the world beyond the mountains, like Uncle Mir.

I was going to England.

As we came closer to Kabul, the road was busier than it had been, with lorries and army trucks and carts. The donkey was nervous in the traffic, so Mother and I were walking. Then we saw ahead of us the police checkpoint. I could tell at once that Mother was terrified. She reached for my hand, clutched it and did not let go. She kept telling me not to be frightened, that it would be all right, God willing. But I knew she was telling herself that, more than she was telling me.

As we reached the barrier the police started shouting at the dog, swearing at her, then throwing stones. One of the stones hit her and she ran off, yelping in pain. That made me really angry, angry enough to be brave. I found myself swearing back at them, telling them exactly what I thought of them, what everyone thought of the police. They were all around us then, like angry bees, shouting at us, calling us filthy Hazara dogs, threatening us with their rifles.

Then – and I couldn’t believe it at first – the dog came back. She was so brave. She just went for them, snarling and barking, and she managed to bite one of them on the leg too, before they kicked her away. Then they were shooting at her. This time when she ran away, she did not come back. After that, they took us off behind their hut, pushed us up against the wall, and demanded to see our ID papers. I thought they were going to shoot us, they were that angry.

They told Mother our papers were like us, no good, that we couldn’t have them back, unless we handed over our money. Mother refused. So they searched us both, roughly, and disrespectfully too. They found nothing, of course.

But then they searched the mattress.

They cut it open, and found the money and Grandmother’s jewellery. The policemen shared out Uncle Mir’s money and Grandmother’s jewellery there and then, right in front of our eyes. They took what food we had left, even our water.

One of them, the officer in charge I think he was, handed me back the empty envelope, and our papers. Then, with a sarcastic grin all over his horrible face, he dropped a couple of coins into my hand. “You see how generous we are,” he said. “Even if you are Hazara, we wouldn’t want you to starve, would we?”

Before we left, they decided to take Father’s donkey too. All we had in the world as we walked away from that checkpoint, with their laughter and their jeering ringing in our ears, were a couple of coins and the clothes we stood up in. Mother’s hand grasped mine tightly. “Walk tall, Aman. Do not bow your head,” she said. “We are Hazara. We will not cry. We will not let them see us cry. God will look after us.”

We both held back our tears. I was proud of her for doing that, and I was proud of me too.

An hour or so later we were sitting there by the side of the road. Mother was wailing and crying, her head in her hands. She seemed to have lost all heart, all hope. I think I was too angry to cry. I was nursing a blister on my heel, I remember, when I looked up and saw the dog come running towards us out of the desert. She leaped all over me, and then all over Mother too, wagging everything.

To my surprise, Mother did not seem to mind at all. In fact she was laughing now through her tears. “At least,” said Mother, “at least, we have one friend left in this world. She has great courage, this dog. I was wrong about her. I think maybe this dog is not like other dogs. She may be a stranger, but as such we should welcome her, and look after her. She may be a dog, but I think she is more like a friend than a dog, like a friendly shadow that does not want to leave us. You never lose your shadow.”

“That is what we should call her then,” I told her. “Shadow. We’ll call her Shadow.” The dog seemed pleased with that as she looked up at me. She was smiling. She was really smiling. Soon she was bounding on ahead of us, sniffing along the side of the road, her tail waving us on.

It was strange. We had just lost all we had in the world, and only minutes before everything had seemed completely hopeless, but now that waving tail of hers gave us new hope. And I could see Mother felt the same. I knew at that moment, that somehow we were going find a way to get to England. Shadow was going to get us there. I had no idea how. But together, we were going to do it. Some way, somehow.

Somehow

Aman

We had to sit there for a long while, until it was dark. We had only the stars for company. Every truck that went by covered us in dust. But we got a lift in the end, in the back of a pick-up truck full of melons, hundreds of them.

We were so hungry by now that we ate several of them between us, chucking the melon skins out of the back as we went along so that the driver wouldn’t find out. Then we slept. It wasn’t comfortable. But we were too tired to care. It was morning before we reached Kabul.

Mother had never in her life been to Kabul, and neither had I. We were pinning all our hopes now on the contact telephone numbers Uncle Mir had written on the back of that envelope.

The first thing we had to do was to look for a public phone. The driver dropped us off in the marketplace. It was the first time in my life I had ever been into a city. There were so many people, so many streets and shops and buildings, so many cars and trucks and carts and bicycles, and there were police and soldiers everywhere. They all had rifles, but there was nothing new or frightening for me about that. Everyone back home in Bamiyan had rifles too. I think just about every man in Afghanistan has a rifle. It was their eyes I was frightened of. Every policeman or soldier seemed to be looking right at us and only at us as we passed.

But then I did notice that it wasn’t us they were interested in so much. It was Shadow. She was skulking along beside us, much closer to us than usual, her nose touching my leg from time to time. I could tell she wasn’t liking all the noise and bustle of the place any more than we were.

It took a while to find a public phone. Mother arranged to meet Uncle Mir’s contact, and at first he was quite welcoming. He gave us a hot meal, and I thought everything was going to be fine now. But when Mother told him we had lost all the money Uncle Mir had sent us for the journey to England, that it had been stolen from us, he was suddenly no longer so friendly.

Mother pleaded with him to help. She told him we had nowhere to go, nowhere to spend the night. That was when I began to notice that, like the police and the soldiers in the street, he too seemed to be more interested in Shadow than in us. He agreed then to let us have a room to stay in, but only for one night. It was a bare room with a bed and a carpet, but after living my whole life in a cave, this was like a palace to me.

All we wanted was to sleep, but this man hung around and wouldn’t leave us alone. He kept asking questions about Shadow, about where we had got her from, about what sort of dog she was. “This dog,” he said, “she is a foreign-looking dog, I think. Does she bite? Is she a good guard dog?”

The more I saw of the man, the more I did not trust him. Shadow didn’t much like him either, and kept her distance. He had darting eyes, and a mean and treacherous look about him. That’s why I said what I did. “Yes, she bites,” I told him. “And if anyone attacks us, she goes mad, like a wolf.”

“A good fighter then?” he asked.

“The best,” I said. “Once she bites, she never lets go.”

“Good, that’s good,” he said. The man thought for a moment or two, never taking his eye off Shadow. “Tell you what, I’ll do you a deal,” he went on. “You give me the dog, and I’ll arrange everything for you. I’ll give you enough money to get you over the border into Iran and all the way to Turkey. You won’t have to worry yourselves about anything. How’s that?”

It was Mother who understood at once what this man was after. “You want her for a fighting dog, don’t you?” she asked him.

“That’s right,” he told her. “She’s a bit on the small side. And a proper Afghan fighting dog will tear a foreign dog like her to bits. But so long as she puts up a good fight, that’s all that counts. It’s not just about size. It’s the show they come to see. Have we got a deal?”

“No, no deal. We are not selling her, are we, Aman?” Mother replied, crouching down, and putting her arm around Shadow. “Not for anything. She’s stuck by us, and we’re going to stick by her.”

That’s when the man lost his temper. He started yelling at us. “Who do you think you are? You Hazara, you’re all the same, so high and mighty. You’d better think about it. You sell me that dog, or else! I’ll be back in the morning.”

He slammed the door behind him as he left, and we heard the key turn in the lock. When I tried the door moments later, it wouldn’t budge. We were prisoners.

Counting the Stars

Aman

The window was high up, but Mother thought if we turned the bed on its side, and climbed up, we might just be able to get out. So that’s what we did. It was a small window, and there’d be a big drop on the other side, but we had no choice, we had to try. It was our only hope.

I went first, and Mother handed Shadow up to me. I dropped Shadow to the ground, saw her land safely, and then followed her. It was more difficult for Mother, and it took some time, but in the end she managed to squeeze herself out of the window and jump down.

We were in an alleyway. No one was about. I wanted us to run, but Mother said that would attract attention. So we walked out of the alley, and into the crowded streets of Kabul.

With lots of other people about, I thought we were safe enough, but Mother said we’d be better off out of Kabul altogether, as far away from that man as we could get. We had no money for food, no money for a bus fare. So we started walking, Shadow leading the way again. We just followed her through the city streets, weaving our way through the bustle of people and traffic, too exhausted to care which way she was taking us. North, south, east or west, it really did not bother us. We were leaving danger behind us, and that was all that mattered.

By the time it got dark, we were already well outside the city. The stars and the moon were out over the mountains, but it was a cold night, and we knew we’d have to find shelter soon.

We had been trying to hitch a ride for hours, but nothing had stopped. Then we got lucky. A lorry was parked up ahead of us, at the side of the road. I knocked on the window of the cab and asked the driver if we could have a ride. He asked where we came from. When I told him we were from Bamiyan and we were going to England, he laughed, and told us he was from a village down the valley, that he was Hazara like us. He wasn’t going as far as England, only to Kandahar, but he was happy to take us if that would help. Mother said we would go wherever he was going, that we were hungry and tired, and just needed to rest.

He turned out to be the kindest man we could have hoped to meet. He gave us water to drink and shared his supper with us. In the warm fug of his cab, we soon shivered the cold out of us. He asked us a few questions, mostly about Shadow. He said he had only once before seen a foreign-looking dog like that, with the American soldiers or the British, he wasn’t sure which.

“They use dogs like this to find the roadside bombs, to sniff them out,” he said, shaking his head sadly. “Those soldiers, the foreign soldiers, they all look much the same in their helmets, and some of them are so young. Just boys most of them, far from home, and too young to die.” After that he stopped talking, and just hummed along with the music on his radio. We were asleep before we knew it.

I don’t know how many hours later, the driver woke us up. “Kandahar,” he said. He pointed out the way to the Iranian frontier on his map. “South and West. But you’ll need papers to get across. The Iranians are very strict. Have you got any papers? You haven’t, have you? Money?”

“No,” Mother told him.

“Papers I can’t help you with,” the driver said. “But I have a little money. It’s not much, but you are Hazara, you are like family, and your need is greater than mine.”

Mother didn’t like to take it, but he insisted. So thanks to this stranger, we were at least able to eat, and to find a room to stay, while we worked out what to do and where to go next. I don’t know how much money the driver gave us, but I do know that by the time Mother had paid for the meal and the room for the night, there was very little left, enough only to buy us the bus fare out of town the next morning. But as it turned out, that didn’t get us very far.

The bus that we had taken, that was supposed to take us all the way to the frontier, broke down out in the middle of the countryside. But it was now a countryside very different from the gentle valley of Bamiyan that I was used to. There were no orchards, no fields here, just desert and rocks, as far as you could see, so hot and dusty by day that you could hardly breathe; and cold at night, sometimes too cold to sleep.

But there were always the stars. Father used to tell me you only had to try counting the stars, and you always went to sleep in the end. He was right most nights. Night or day we were always thirsty, always hungry. And the blister on my heel was getting a lot worse all the time, and was hurting me more and more.

After walking for many days – I don’t know how many – we came at last to a small village, where we had a drink from the well, and rested for a bit while Mother bathed my foot. The people there stood at their doors and looked at us warily, almost as if we were from outer space.