скачать книгу бесплатно

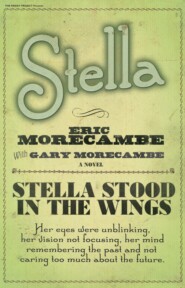

Stella

Gary Morecambe

Eric Morecambe

The final novel from comedy legend Eric Morecambe.Charting the rise of Stella Ravencroft from struggling entertainer on the northern club circuit to huge national superstar, Stella was the second novel from comedy legend Eric Morecambe.The unfinished manuscript for Stella was discovered by Eric’s son, Gary, shortly after his father’s death. Encouraged by Eric’s wife Joan, Gary completed the novel.Drawing heavily on Eric’s own childhood and rise to fame, Stella is a rare fictional account of a now vanished era of entertainment, from working men’s clubs to variety shows pulling in 20m viewers on the television.

STELLA

ERIC MORECAMBE

with GARY MORECAMBE

Dedication

This book is dedicated to the memory of my father-in-law, Major Derek Allen, who in the short time I knew him managed to teach me the many benefits of self-confidence.

Also to the doctors and staff at Harefield Hospital to whom my family are ever indebted for the five extra years of life they gave to my father.

And my thanks to Susan Mott who so patiently and efficiently typed out the final draft copy of STELLA for me.

G. M. 1986

Contents

Cover (#ub2faa3ee-fabc-5466-a771-e51dc399d5ed)

Title Page (#u3b2cb317-354d-5ca8-b0b8-5446a076b43c)

Dedication

Introduction

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Epilogue

Copyright

About the Publisher (#u0c9b54ac-7ccd-5fda-b665-1c8bf3780dfd)

Introduction

It must have been about two days after my father’s untimely death that I ventured into his upstairs office.

It had taken some courage to do this, because this book-laden room was his shrine, and almost every previous time that I had entered it I had discovered his hunched figure poised over his portable typewriter, the whole room engulfed with smoke from his meerschaum pipe.

The acrid smell of stale tobacco still lingered, and would continue to for weeks to come. The silent typewriter was still sitting in the position it had been when my father had last sat in front of it. I would have paid no more attention, had it not been for the sheet of paper that caught my eye.

Headed STELLA, P. 61, there were only about eight typed lines on the sheet. I cannot wholly recall what they said, but it was enough to remind me that my father had been deeply involved in what would have been his second novel.

Intrigued, I began a search for notes, pages, anything that had been destined for the novel. It was remarkable just how much turned up considering that he had never before kept many notes. But then, as we discovered shortly after his death, it was as though he knew that something was going to happen to him, because he had tidied up most aspects of his life from taxation to photo albums.

Anyway, by the end of that day spent searching, I had gathered nearly two thirds of the manuscript – some completed, some merely in note form.

I asked my mother how she would feel about me taking on the project of finishing the novel. ‘It’s a good idea,’ she said. ‘He had spent much of his time on it. It would be nice to see it finished.’ And so my first draft of STELLA went into production.

He had often talked to me about STELLA, quoting lines from it, showing me the latest passage he was working on, and explaining that the background would be very similar to his own. I would smile and listen attentively, glad to see the pleasure it was giving him, but totally unaware that day I would desperately be racking my brain for those little snippets of information he had casually given to me.

Stella’s background is very similar to his own. She even plays in the streets he played in when he was a boy. In fact, the pattern of Stella’s career is not so different from his own, though I’m sure he won far more talent competitions than poor Stella is allowed to win in this story.

While the characters are not based on particular individuals, there is a sense of recognition about them. They suit the story so well, one can’t help but assume that they closely resemble many of the people my father had to contend with on his way to the top.

Perhaps it was because most of the work I did on this book was carried out at the same desk in the same favourite office of my father’s that I felt he was ever-present, and always there to give me a guiding hand. And during the more hilarious pieces I worked on I am convinced I could hear him chuckling over my shoulder at his own lines. So, in a strange way, I feel we worked at the book together and not independently.

The office has altered very little during the last two years and I still often use it, convinced it is a source of great inspiration to me.

My father’s notes on STELLA are now blended with mine in brown and blue cardboard folders that line a shelf of the study. They represent the months of pleasure I derived from putting the novel together. I hope you derive as much pleasure from reading it.

Gary Morecambe

1968

Chapter One

Stella stood in the wings. Her eyes were unblinking, her vision not focusing, her mind remembering the past and not caring too much about the future. Somehow she had managed to reach the theatre through her haze of confusion, to change into the right clothes and prepare to face an ecstatic audience.

But she hadn’t felt it had been she who had done these things: it wasn’t she who was the star of the show and who was supposed to now be enthralling and entertaining some of her vast following who had paid to see her that night. She remembered the letter. She would always remember that letter until the day she died. She shuddered: death wasn’t a subject she wanted to think about.

She gave an ironic laugh that more resembled a cough, and thought of her sister.

Fifteen years ago she couldn’t have begun to guess at what life held for her – the tears, the joy, and the horror.

It had started as a dream, and as if by magic had been transformed into reality.

Like the letter, she would always remember the last fifteen years of her life most vividly . . .

The change in what could only be described as a typical, unexceptional, northern upbringing of the early part of the twentieth century began in Lancaster in 1924. During that year, Stella Ravenscroft grew into a sprightly ten-year-old and her sister, Sadie, into a more subdued eight-year-old. They were inseparable chums, though Stella made sure her sister knew who was boss, and it was something Sadie would never be allowed to forget.

It was a bleak January that had hailed the beginning to that year, the city being buried beneath an unmoving thin white carpet of crisp snow. Returning home from school one evening during that month, Sadie revealed that she had heard that Tommy Moran – Stella’s childhood sweetheart – had been kissed by Molly Chadwick.

‘Whereabouts did she kiss him?’ demanded Stella.

‘On the mouth,’ innocently replied her sister.

‘No. I mean where? You know – where?’

‘Oh. Outside the tobacconist’s on’t corner of Penny Street.’

Stella threatened to give her sister a Chinese burn if she didn’t expand on her story of the event. As she roughly grabbed her wrists Sadie blurted, ‘Winnie Robinson told me.’

‘When?’

‘This morning.’

‘Tommy kissed Molly this morning, eh?’

‘No,’ she said. ‘Winnie told me this morning.’ Then she added, ‘And you know that Winnie never tells lies.’

Stella released her prisoner, if only for the time being.

The familiar greyness of Corkell’s Yard loomed up before them as it always did when they neared Penny Street. It was an unremarkable collection of grim-looking buildings, and if you closed your eyes there wasn’t a single definite feature that would come to mind. Yet the two whitewashed cottages and one wooden shack that held a bench lav was home.

They pulled up short of the yard so Stella could give the tobacconist’s some scornful glances. Sadie asked her in a whisper, ‘Are you never going to forgive Tommy, now he is not pure?’

‘Them’s private matters,’ she replied brusquely, ‘and certainly not for the ears of younger sisters.’

Sadie was well acquainted with Stella’s manner and just mouthed an ‘Oh’, before digging into her pocket to pull out a boiled sweet she had been saving.

She dropped it into the snow and Stella gave a short, derisive laugh. Unabashed, Sadie bent down, picked it up, and popped it into her mouth.

Stella winced with mock revulsion, and said, ‘I’m going to tell our Mam. It’s disgusting, is that.’ She didn’t add that she was jealous she hadn’t a boiled sweet to eat.

‘Tell-tale tit, yer tongue be split,’ retorted her sister, and at once took flight in the direction of Corkell’s Yard and the safety of home. Stella was a fast runner, and in spite of Sadie’s lead they entered the tiny house together.

In the downstairs room there was a gas light, and an oil lamp on the window ledge but it was rarely lit, and now was no exception. Next to it a candle lay horizontal on a chipped green saucer, where it had fallen the previous night and hadn’t been uprighted again. Both box-like bedrooms upstairs had a candle of their own, and the one in their parents’ room had a proper candle holder.

In winter they were grateful for the cooking range as it kept the rooms warm, but in summer it kept them hot. The planked front door had a thick curtain across it on the inside, supposedly to help shield against the draughts, but it was so full of tears and holes that it had become more of a hindrance than a help.

Mrs Ravenscroft ensured that their house was kept in a sustained state of cleanliness but she didn’t extend this virtue upon herself. The range was as black and shiny as a full bottle of Guinness and the windows were washed daily. Her saying was, ‘Cleanliness is next to godliness, but in Corkell’s Yard it’s next to impossible.’

She was smiling to herself about her saying when the sound of her daughters’ feet cracking against the iced cobblestones caught her attention. Instinctively she glanced across the kitchen to a battered cuckoo clock that for many years had given out the incorrect time. It was a habit of hers to check the time. She liked to note how long it had taken them to get from school back to home and, of course, always took into account the temperamental nature of the clock.

‘Hello, Mam,’ cried both girls.

‘Wipe your feet,’ came the firm response, but it was delivered in a gentle way. They both immediately back-stepped to the doormat.

‘What’s for tea, Mam?’ asked Sadie, always first to make enquiries on the food situation.

‘Balloons on toast,’ kidded her mother with a little smile forming on her lined face.

She was a tall woman with a frail frame, and the only secret she’d ever kept was her age. She never lied about this, she merely stated that she was the same age as her sister-in-law, Mildred from Carlisle, and then lied about her age.

Her father was called Sven Ronnorf and was Swedish. Her mother, Daisy, was pure Lancashire. Both had been dead for some years, or at least, as Jack Ravenscroft would say, ‘I hope they’re dead – we buried ’em.’ Ronnorf had been a stoker on a Swedish cargo vessel that used to bring wood to the Lancaster Docks. Then, in 1885, having met Daisy several times, he proposed to her, married her, and settled in Lancaster.

Lilly was very proud, if not a little touchy, about her Swedish background. Although born in Lancaster, and unable to speak more than two or three Swedish words, none of which were clean, she would proudly tell her daughters all about life in Sweden, as though she had spent most of her own life there.

Stella and Sadie couldn’t wait to visit this mysterious land, having heard from their mother how they lived off giant black puddings and green shrimps.

‘Go on, Mam. What’s for tea?’ Sadie pressed.

‘I’ve told you once. It’s balloons on toast, and you’ll have to eat them quick before they fly away.’

‘No, Mam, truthfully,’ she pleaded. Stella always ignored all this mundane twaddle, as she called it. She knew it was all a tease and that it would conclude in them having a normal tea.

Stella peered out of the window at the house next door, hoping to catch a glimpse of Tommy Moran. Tommy was quite nice even though he was supposed to have kissed Molly Chadwick, she thought. He was certainly more likeable than his younger brother Colin. He was horrible, and his nose was always running.

‘Your father will be in within the hour and it’s his favourite, so I thought you could have a mug of tea and a biscuit to tide you over ’til he’s here.’

‘Oh, yes,’ gasped Sadie, squeezing her hands together with anticipation. ‘It’s a fry-up, isn’t it? I know that’s Dad’s favourite.’ She licked her lips as she pictured a plate full of crispy bacon, fried bread, sausages, and fried potatoes – and, of course, a mountain of brown sauce.

Stella pulled a long face that was full of disappointment. ‘And what’s up with the Queen of England, then?’ asked her mother. Sadie turned to see her sister still peering through the window onto the dimly lit yard.

‘She’s jealous ’cos Molly Chadwick kissed Tommy Moran,’ she said quickly.

‘I’m not,’ Stella screamed back at her sister, desperately enough to make her mother realise she was.

Having committed herself to this accusation, Sadie dived back in with ‘And she kissed him on the mouth.’