скачать книгу бесплатно

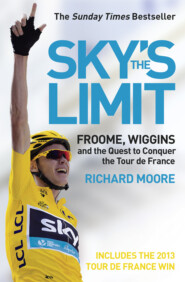

Sky’s the Limit: Wiggins and Cavendish: The Quest to Conquer the Tour de France

Richard Moore

On Sunday 22 July, Bradley Wiggins became the first British rider ever to win the Tour de France. It was the culmination of years of hard work and dedication and a vision begun with the creation of Team Sky. This is the inside story of that journey to greatness.On Sunday 22 July, Bradley Wiggins became the first British rider ever to win the Tour de France. It was the culmination of years of hard work and dedication and a vision begun with the creation of Team Sky. This is the inside story of that journey to greatness.Sky’s the Limit follows the gestation and birth of a brand new road racing team, which is the first British team to compete in the Tour de France since 1987. Team Sky, as it is known, since it is to be backed by the satellite broadcaster Sky, set out on the road to Tour de France glory in January 2010.With exclusive behind-the-scenes access and interviews, Sky’s the Limit follows the management and riders as they embark on their journey - from their first training camp and team presentation in December 2009, all the way to the moment that Bradley Wiggins achieved what many had long thought impossible: a British rider from a British team winning the Tour de France.

CONTENTS

Cover (#u23fb87e3-6fd5-5261-950f-31c3fc41c5a6)

Title Page (#uc35c042b-360a-5a0a-925d-fdc2987aff61)

Prologue The Start of the Journey (#ulink_a1bd8d5f-7928-59b6-80b2-3922aec56acc)

Chapter 1 Critical Mass (#ulink_301cde18-a151-53c8-bf82-08620c953cf6)

Chapter 2 The Academy (#ulink_31afc0c9-2042-5a49-b20c-f039feb1f1d5)

Chapter 3 Goodbye Cav, Hello Wiggo?

Chapter 4 The Best Sports Team in the World

Chapter 5 Unveiling the Wig

Chapter 6 A Tsunami of Excitement

Chapter 7 Taking on the Masters

Chapter 8 Pissgate

Chapter 9 The Classics

Chapter 10 The Recce

Chapter 11 It’s All About (the) Brad

Chapter 12 It’s Not About the Bus

Chapter 13 So Far from the Sky

Chapter 14 Take Two

Chapter 15 Gerbils on a Treadmill

Chapter 16 La Promenade des Anglais

Chapter 17 Froome Power

Acknowledgements

Index

Picture Section

Copyright

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE (#ulink_0a8ab6cd-9b17-5f2f-8f87-5dc6d5889ece)

THE START OF THE JOURNEY (#ulink_0a8ab6cd-9b17-5f2f-8f87-5dc6d5889ece)

‘They’ll use technology that we’re all going to look at and go, “Woah, I never saw that before.”’

Lance Armstrong

Rymill Park, Adelaide, 17 January 2010

It’s a sultry hot summer’s evening in downtown Adelaide, and, at the city’s Rymill Park, a large crowd begins to gather. Families line a cordoned-off rectangular 1km race circuit, around the perimeter of the park, while the balconies of pubs fill up with young people drinking beer out of plastic cups.

The road cycling season used to start six weeks later in an icily cold port on the Mediterranean, with the riders wrapped in many more layers than there were spectators. But the sport has changed in the last decade: it has gone global. And no event demonstrates that to the same extent as the season-opener: the Tour Down Under.

This year, though, there is another harbinger of change. Possibly. Wearing a neatly pressed short-sleeved white shirt, long black shorts and trainers, rubbing sun cream into his shaved head as he paces anxiously among the team cars parked in the pits area, is a man who bears more than a passing resemblance to a British tourist. It’s Dave Brailsford.

In his native Britain, Brailsford has gained a reputation as a sporting guru. Since 2004 he has been at the helm of the British Cycling team, which, at the Beijing Games in 2008, he led to the most dominant Olympic performance ever seen by a single team. But that was in track cycling, not road cycling. Road cycling – continental style – is a whole new world, not just for Brailsford but for Britain, a country that has always been on the periphery of the sport’s European heartland.

There have been British professional teams in the past. But they have been, without exception, doomed enterprises, Icarus-like in their pursuit of an apparently impossible dream. The higher they flew – to the Tour de France, as one particularly ill-fated squad did in 1987 – the further and harder they fell. And the more, of course, they were burned in the process. In fact, it seems oddly fitting that after more than a century of looking in on the sport with only passing interest, and limited understanding, Adelaide in Australia, on the other side of the world, marks Brailsford and his new British team’s bold entry into the world of continental professional cycling.

Bold is the apposite word. Everything about the new team, Team Sky – from their clothing, to their cars, to the brash and glitzy team launch in London just days earlier – screams boldness and ambition. They don’t just want to enter the world of professional road cycling. They aspire to stand apart; to be different. And by being different, and successful, they aspire to change it, almost as the team’s sponsor, British Sky Broadcasting, has changed the landscape of English football over the past two decades; almost as Brailsford and his team ‘changed’ track cycling, not merely moving the goalposts, but locating them in a different dimension.

Team Sky is Brailsford’s creation, along with his head coach and right-hand man, Shane Sutton. Sutton, a wiry, rugged, edgy, fidgety Australian, is the joker to Brailsford’s – with his background in business and his MBA – straight man. They are as much a double act as Brian Clough and Peter Taylor, the legendary football management team. And similarly lost without each other. Here in Adelaide, an hour before the first race of the season, and the first of Team Sky’s existence, Sutton is missing. Brailsford keeps checking his phone and finally it beeps. ‘The eagle has landed,’ reads the text message. Sutton’s delayed flight from Perth has arrived. Brailsford looks relieved. ‘Well, Shane needs to be here for this,’ he says.

Sutton arrives. Has he brought champagne, ready to toast the occasion? ‘Nah, none of that bullshit,’ he replies testily. He is wearing the same team-issue outfit as Brailsford; but if Brailsford looks like a businessman on holiday, Sutton, in his white shirt and long black shorts, has the mischievous, scheming air of a naughty schoolboy. Brailsford reaches into the giant coolbox parked in the shadow of the team car and pulls out a couple of cans of Diet Coke, tossing one at Sutton. They open their cans, take a swig, and wait for the action, which is just minutes away.

Brailsford has hurried back to Rymill Park from the team’s hotel, the Adelaide Hilton, where he gave the seven Team Sky riders – Greg Henderson of New Zealand, Mat Hayman and Chris Sutton of Australia, Russell Downing, Chris Froome and Ben Swift of Britain, Davide Viganò of Italy – a pep-talk. Earlier, the riders had been presented on stage by the TV commentators, Phil Liggett and Paul Sherwen. ‘I never thought I’d see the day we’d have a British team in the ProTour,’ said Sherwen. The ProTour is cycling’s premier league of major events.

Though all experienced professionals, most of whom have competed for big teams, the seven Team Sky recruits find themselves riven with nerves as they prepare for their debut. The dead time between the presentation of the teams in the middle of Rymill Park and the start of the race acts as a black hole into which spill fears, doubts and anxieties. ‘We were all nervous, just sitting around, waiting,’ Mat Hayman will recall later. ‘Pulling on the new kit, being given this opportunity to be part of this new team … We all know what’s gone into this team: more than a year’s work, so much thought and organisation. We’re excited about it, too, because we’ve all bought into what Dave and Shane and Scott [Sunderland, the senior sports director] are trying to do. And we all said that it had been a while since everyone had been so nervous about lining up.’

Just before they left the hotel, to pedal the 10 minutes to Rymill Park, Brailsford addressed them. ‘This is a proud moment for me,’ he said. ‘And it’s a unique occasion. We’re only going to make our debut once. This is it, lads. It’s a privilege. Enjoy it.’

Brailsford had been in Adelaide for 48 hours ahead of the big kick-off, with Sunday evening’s circuit race followed, two days later, by the six-day Tour Down Under. He had checked into the Hilton late on Friday evening and then wandered into the hotel lobby. ‘I’m a worrier,’ he said. ‘I always worry. I’m always wondering, what if we’d done this, or that. I’m sure that’ll never change, but I’m confident that we’ve done everything we could to prepare. It’s a huge moment. I’m excited.’ But he sought to add a note of caution. ‘You can’t go from having a group of individuals come together in Manchester to an elite team in six weeks,’ Brailsford pointed out. ‘It’s a process.’

Despite the late hour, Brailsford drank a coffee, then another. And he kept talking, stopping only to yell at Matt White, the director of a rival team, Garmin-Transitions, as White walked through the lobby. ‘Hey, Whitey!’ he yelled, though White didn’t appear to hear him. ‘Whitey!’

Brailsford seemed out of his comfort zone, which, for several years, has been the centre of a velodrome, surveying his riders as they circle the boards of the track, talking to his coaches, in conference – arms folded – with Shane Sutton. With Team Sky, Brailsford’s job title is team principal, which seems a bit vague (and, again, different), other than in one important respect: he’s the man with overall responsibility. But on the ground, during races, the sports directors will call the shots. Here in Adelaide the man in that role is one of the team’s four sports directors, Sean Yates, an experienced British ex-professional; indeed, a former stage winner and wearer of the yellow jersey in the Tour de France. Yates has been overseeing the team’s training all week in Adelaide.

It is clear that Brailsford, having just arrived, isn’t quite sure yet of his role. This is not his world; not yet. He wants to focus, however, on the bigger picture; on the many races in the early part of the season, and the spring Classics, all leading up to Team Sky’s major target, the Tour de France, where they will be aiming to support their leader and homegrown talisman, Bradley Wiggins, in his bid for a place on the podium in Paris.

‘People keep asking, “What would be a good race for us here, or what would make a good season?”’ says Brailsford. ‘The important thing is to try and not underperform. We’re trying to create an environment in which the riders can perform to the very best of their ability. So if they underperform, we’re doing something wrong.’

In Rymill Park the first-day-of-term feeling means an intoxicating sense of excitement combined with nervous anticipation; of new teams and new outfits; of glistening new bikes; of gleaming legs, unblemished by the scars and road rash that will disfigure them in the weeks and months to follow; of excitable Australian fans, who in previous years have only been able to watch the great European stars of the sport on television, and at night. Everything is shiny and new, except for 38-year-old Lance Armstrong, leading his new RadioShack team into the second year of his comeback.

In the pits, immediately after the first bend of the 1.1km circuit, the team cars are lined up, side by side, with the Team Sky vehicle – a Skoda, supplied by the sponsor, rather than their usual Jaguar – flanked by Française des Jeux and Astana, then Garmin-Transitions and HTC-Columbia. Brailsford and Sutton slap their riders on the backs and whisper encouraging words as they leave the shaded area behind the car and pedal to the start.

‘We’ve got a game plan,’ says Brailsford as he and Sutton perch on the bonnet of the car. Planning to the nth degree is what Brailsford is most famous for. But he and Sutton look apprehensive and on edge as they await the countdown and the firing of the gun.

In contrast is Bob Stapleton. As the owner of the rival HTC-Columbia team, Stapleton’s position is similar to Brailsford’s. Stapleton is the man in charge, but he has always appeared relaxed in that role. Typically, he can be found hovering around the fringes of his team in the mornings, chatting easily to journalists. Like Brailsford, Stapleton tends to be viewed as something of an outsider in a sport which has a reputation for being resistant to, and suspicious of, outsiders. He was a millionaire businessman in his native California before being parachuted in to clean up and manage one of the world’s top teams in 2006. But since then he seems to have overcome any suspicion or hostility. His manner is amiable and open: that must help. But it helps even more that his team, HTC-Columbia, is successful, and wins more races than any other.

Now, as the first race of the 2010 season gets underway, Stapleton wanders away from his own team car and strolls towards Brailsford and Sutton. But he doesn’t quite make it that far, stopping and sitting on the bonnet of the Astana team car, whose staff, in animated conversation, are sitting on the tailgate, facing away from the action. (Such apparent disinterest among people working at this level of the sport can be fairly typical, if slightly unusual at the first race of the season. It suggests a certain complacency in some teams, which Brailsford has already identified as an opportunity.)

In his Columbia clothing – gentle beige and pastel turquoise – Stapleton, as he smiles and asks, ‘Mind if I join you guys?’, and settles on the bonnet of the Astana car to watch the action unfold, appears as laidback as a millionaire Californian cycling enthusiast who has been able to indulge his passion for cycling by running his own team. Which he is. His sports director, Allan Peiper, cuts a less relaxed figure by the HTC car, an earpiece and microphone connecting him to his riders, and making him look like a bouncer in a rowdy football pub. Sutton and Brailsford are sitting on the bonnet of the Team Sky car, with Sean Yates in close attendance. But Yates is not linked up by radio to his riders. ‘Our boys know what they’re doing,’ says Sutton.

What they appear to be doing, in the early part of the race, is remaining as invisible as possible. Attacks are launched – the young Australian Jack Bobridge is particularly aggressive – and brought back by a peloton that seems to be quickly into the speed, and rhythm, of racing. But at half-distance a break goes clear and stays clear. It includes Lance Armstrong. ‘He’s a guy with a lot going on this year,’ observes Stapleton cryptically (though also presciently).

Armstrong is joined by four other riders, and they work well as a quartet, building a lead that stretches to almost a minute over the peloton. Still Team Sky, in their distinctive, predominantly black skinsuits, are anonymous, hiding somewhere in the middle of the pack. Brailsford and Sutton remain perched on the bonnet of the car, apparently content that the plan is being followed, though there’s a moment of panic when Ben Swift appears after the bunch has passed, the spokes having been ripped out of his rear wheel by a stray piece of wire. The young British rider is given a spare bike, pushed back on to the course, and quickly rejoins the bunch.

While Brailsford and Sutton focus on the race, Stapleton watches with what appears to be amused detachment. He wonders aloud whether, without ProTour status, this circuit race in central Adelaide – really only a curtain-raiser to the main event, the Tour Down Under – even counts as the first race of the season.

‘If we win, it is the first race of the season,’ decides Stapleton, with a twinkle in his eye, after giving it some thought. ‘If we don’t, it doesn’t matter.’

The Armstrong break is allowed to dangle out in front long enough for the crowd to start to believe that the American might win. But with four laps to go Stapleton’s HTC squad hits the front, a blur of dazzling white and yellow leading the peloton as they fly past the pits area, travelling noticeably, and exhilaratingly, faster.

‘Oh yeah, now we go,’ says Stapleton. Shadowing Stapleton’s team, though, are five Team Sky riders, packed equally tightly together. And shadowing is the word: in their dark colours they look sinister, menacing.

On the next lap HTC still lead, Sky still follow. But the next time, with two to go, the speed has gone up again, and the HTC ‘train’ of riders has been displaced from the front: now it’s Sky who pack the first six places, riding in close formation, with Greg Henderson, their designated sprinter, the sixth man. ‘That’s all part of the plan,’ says Stapleton with a chuckle.

True enough: HTC surge again, swamping Sky. And in previous seasons that would have been it: game over. But Mat Hayman leads his men around HTC and back to the front; then he leads the peloton in a long, narrow line for a full lap. Once Hayman has swung off, HTC draw breath and go again, but Sky have the momentum now, and they’re able to strike back. On the final lap, the two teams’ trains are virtually head to head – they resemble two rowing crews, as separate and self-contained entities – until the final corner, when HTC’s sprinter, André Greipel, commits a fatal error: he allows a tiny gap to open between his front wheel and the rear wheel of his final lead-out man, Matt Goss. It is a momentary lapse in concentration, or loss of bottle by the German, but the margins are tiny at this stage of the race, and there isn’t time for Greipel to recover. Henderson has been sitting at the back of the Sky ‘train’, watching his handlebar-mounted computer read 73kph (‘I thought, “Holy shit! I’ve never been in such a fast lead-out train”’), and now, as they enter the finishing straight, Henderson’s lead-out man, Chris Sutton, dives into the gap created by Greipel’s hesitation. And as Goss begins to sprint, Sutton and Henderson strike.

On the final lap Brailsford and Sutton leapt from the bonnet of the car as though the engine had been turned on. They sprinted to the first corner, where a big screen had been set up, and they watched as Henderson and Sutton sprinted for all they were worth up the finishing straight, passing Goss, and both having time, just before the line, to look round and sit up, their hands in the air, to celebrate a fairly astonishing one-two.

Brailsford and Sutton punch the air and embrace each other, before Brailsford disappears into a huddle of journalists. But Stapleton appears and stretches over to shake hands. ‘You guys can see,’ says Stapleton, ‘I was the first to congratulate him. Congratulations, Dave, that was terrific.’

Even the languid, laidback Sean Yates is overjoyed. He high-fives the riders as they return to the car. ‘I think other teams will look at that and think, they’ve just rocked up, put six guys in a line, they looked fucking mean, and they won the race,’ says Yates.

‘Textbook,’ says Sutton. ‘But I’ve never seen Dave so stressed. With a lap to go I gave him my stress ball. He was pumping it like nobody’s business. Look, I’m here because Dave wanted me to fly over and be here. We shook hands at the start of this race, and said this is the start of the journey, but this is about other people’s expertise. They’ve done the hard yards. But being part of this,’ adds Sutton as he turns to embrace his nephew, the second-placed Chris, ‘is absolutely fantastic.’

Brailsford and Sutton also know the value of a good start to any campaign. They think back to Beijing, to day two of the Olympics, when Nicole Cooke won a gold medal in the women’s road race. It was a performance that galvanised the track team, inspired them and injected momentum, before they themselves went out and won seven gold medals. But what is most encouraging about the one-two in Rymill Park – for all that it is only a criterium; for all that it is only the hors d’œuvre to the Tour Down Under – is that it involved the execution of a plan; and that, in taking on HTC-Columbia in setting up a bunch sprint, they had beaten the world’s best exponents of this particular art.

It was encouraging. But Brailsford was more than encouraged; he was buzzing. Already aware that there had been some sniping, and lots of scepticism over his stated plans and ambitions, not least his intention to do things differently, he now hits back: ‘Some people seem to think we ride round in circles [in velodromes] and don’t know what we’re doing, but we know what lead-outs are, and we know what sprinting is about from the track.

‘Some people are saying this team’s all about marketing, flash and razzmatazz, and all the rest of it,’ he continues. ‘But we’d talked that finish through. That’s what we do. The race was predictable. Not the win, but the pattern the race would follow – a break going, and being brought back at the end. We knew what was going to happen, and that it’d come down to the last couple of laps. So you plan for that. You have to have a plan.’

And nobody could argue: day one had gone to plan.

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_f47af410-d893-5c3f-8102-a38d06f9c738)

CRITICAL MASS (#ulink_f47af410-d893-5c3f-8102-a38d06f9c738)

‘I thought, bloody hell, what are you supposed to do? Sit up? … This is the Tour de France – you don’t sit up.’

Bradley Wiggins

Bourg-en-Bresse, 13 July 2007

It had been a typical flat, early stage of the Tour de France. Typical, that is, unless you happened to be British.

Stage six, 199.5km from Semur-en-Auxois to Bourg-en-Bresse, rolled through flat but beautiful Burgundy countryside, past golden fields, sprawling stone farms and proud châteaux. But amid the usual flurry of attacks in the early kilometres, from riders eager to feature in the day’s break, one man went clear on his own.

He was up near the front of the peloton, ideally positioned for the waves of attacks. He followed one of those accelerations, then looked around to see that he had four riders for company, with daylight between them and the peloton. A gap! Perfect. And so he put his head down, tucking into a more aerodynamic position, and pressed hard on the pedals, making the kind of effort that had propelled him to his Olympic and world pursuit titles. When he turned around again he saw that he was alone. He wasn’t sure what had happened, whether his companions had been dropped or given up. And he wasn’t sure what to do. So he kept going.

Bradley Wiggins, riding for the French Cofidis squad, carried on riding alone, elbows bent, beak-shaped nose cutting through the wind, long, lean legs slicing up and down to a relentless beat, for kilometre after kilometre after kilometre. While the peloton ambled along behind him, content to let the solitary rider up front flog himself, the Englishman built a lead that stretched to an enormous 16 minutes. At that point there was around 9km, or 6 miles, between him and the others. It was an unusual way to do it. And it was probably doomed to failure. But Bradley Wiggins was finally making his mark on the Tour de France.

The previous year, when the then 26-year-old Wiggins had finally ridden his first Tour, he was one of only two British riders in the race, the other being David Millar, returning from a two-year suspension for doping. Wiggins seemed like a square peg in a round hole. He was the Olympic pursuit champion, a track superstar and a road nobody. For five seasons, since turning professional with the Française des Jeux team as a raw 21-year-old in 2002, Wiggins had drifted around some of the most established, most traditional teams in the peloton – from FDJ to Crédit Agricole – before moving on to a third French outfit, Cofidis, in 2006.

To observers, road racing seemed more like a hobby than a profession. It was what Wiggins did when he wasn’t preparing for a world championship or Olympic Games. He was fortunate to be in teams that indulged him in his track obsession; or perhaps they just didn’t care, and could afford to write off his salary – starting at £25,000, rising to £80,000 – or regard it as a small investment in the British market. Although any interest his teams’ sponsors – the French national lottery, a French bank and a French loans company – had in the British market must have been, at best, negligible.

Most mornings during his first Tour, Wiggins would leave the sanctuary of his team bus. He would swing his leg over his bike and weave through the crowds to the signing-on stage. Then he would head for the Village Départ, where entry is restricted to guests, VIPs, accredited media and riders – though in the era of luxury team buses, few riders deigned to appear. Wiggins was different. He liked to read the British newspapers and drink coffee with British journalists in the Crédit Lyonnais press tent.

About halfway through his debut Tour, as he waited one morning in the Village Départ for his wife, Cath, who was over to visit, Wiggins was asked how he was finding the race. ‘Um, I think I can win this thing,’ he said. He missed a beat before cracking a wry, self-deprecating smile. The idea was ridiculous. It confirmed his image – and indeed his self-image – as an outsider.

Not that he was a disinterested outsider. Wiggins’ knowledge of the Tour de France, his respect for it, and his awe of its champions, was obvious; he just didn’t seem to understand what he, Bradley Wiggins, was doing there, or what, if anything, he could bring to the party. Rather, he resembled an English club cyclist parachuted into the biggest race in the world; he seemed oblivious to, or in denial of, his talent.

On another occasion Wiggins sat drinking coffee and reading the papers a little too long. One of his Cofidis directors came hurrying over, shouting: ‘Brad! Allez!’ The race had left without him. Amid scattered newspapers and upturned cups of coffee, Wiggins shot up, grabbed his bike, pedalled hastily across the grass and bumped on to the road just in time to join the tail end of the vast, snaking convoy of vehicles that follows the race, working his way through that and finally into the peloton to survive another day. After three weeks he finished 123rd in Paris. But to the extent that any rider who finishes the Tour can do, he left no discernible trace.

In 2007, his second Tour is proving a little different. He finishes fourth in the prologue time trial, and, with his great escape on stage six to Bourg-en-Bresse, Wiggins is at least getting himself noticed. For five hours he hogs the TV pictures, which depict him toiling for mile after solitary mile. The landscape flashes past, but it is as though Wiggins, in his post box red Cofidis kit, is part of it. Several observers remark on his style, his smoothness, his élan. ‘Il est fort,’ they say, ‘un bon rouleur.’

Halfway through the stage Wiggins’ lead over the peloton is down to 8 minutes, 17 seconds, still a considerable margin. He continues to look strong; the effort effortless. And among some of the journalists gathered around monitors in the press room a theory emerges as to the motivation for his lone attack. The clue is in the date: 13 July. It’s 40 years to the day since Britain’s only world road race champion, Tom Simpson, collapsed and died on Mont Ventoux, while riding the 1967 Tour. Wiggins is a patriot with a keen sense of cycling history; the type who could tell you not only the date of Simpson’s death, but what shoes he was wearing.

So that explains it: Wiggo’s doing it for Tom.

Approaching Bourg-en-Bresse, it even seems that he may defy the odds – and the sprinters’ teams, now pulling at the front of the peloton as they pursue their quarry – and hang on to win. But as he rides into the final 20km – stopping briefly to replace a broken wheel, throwing the offending item into the ditch as his team car screeches to a halt behind him – and Wiggins hits a long, straight expanse of road, the wind picks up. It blows directly into his face, and presents a serious handicap. The peloton can always move significantly faster than a small group or single rider; but especially into a headwind.

As Wiggins passes under the 10km to go banner, his lead having disintegrated, he is a dead man pedalling. The peloton leaves him dangling out front before casually swallowing him up with 6km to go. One of the helicopter TV cameras lingers on Wiggins as riders stream past and he drops through the bunch, and straight out the back.

Tom Boonen of Belgium wins the bunch sprint and is swamped by reporters and TV crews as he slows to a halt beyond the finish line. Other riders attract their own mini-scrums. Finally, after a long 3 minutes, 42 seconds, Wiggins appears – the 183rd and last man to cross the line. As he comes to a weary halt and wipes his salt-caked face with the back of his mitt he also attracts a mini-scrum.

So was it for Simpson? ‘Sorry?’ replies Wiggins. Today is the anniversary of Simpson’s death, he is told.

‘Nah, nah. I didn’t realise,’ he shrugs. ‘But it is my wife, Cath’s, birthday. She’ll be watching on TV at home with the kids. I suppose it was the closest I could get to spending the day with her.’

To the journalists’ disappointment, he admits that it wasn’t planned. ‘There were five of us in a little move at the start, I pulled a big turn, looked round and saw I was on my own. You don’t choose to end up on your own like that, it just happens. I thought, bloody hell, what are you supposed to do? Sit up? … This is the Tour de France – you don’t sit up. So I thought I’d continue. When I got a minute I thought there’d be a counterattack and some bodies would come across to me, but that never happened. So I just kept going.

‘When I got 10, 15 minutes, I thought maybe it could happen and I could win the stage. Even at 15km to go I thought it might happen, but it was that bloody headwind towards the finish. I was still doing 45kph, but I knew they’d be doing 52 or 53. At 10km I knew really that I had no chance with that headwind.’

Still, it was a day on which Wiggins could look back with pride. And he’d earned himself a first-ever trip to the podium, the steps of which drained the last ounces of energy from his legs, to receive le prix de la combativité – the day’s award for most aggressive rider.

Two places in front of Wiggins, having also been dropped by the main pack as the speed picked up towards the finish, another British rider had gone past as we waited for Wiggins. He was young, it was his debut Tour, but grave disappointment was etched on his face in the form of an angry scowl. It was Mark Cavendish, and his much-anticipated debut in the biggest race in the world was one of the main reasons for the appearance in Bourg-en-Bresse of Dave Brailsford, the British Cycling performance director.

An hour later, with the dust settling on the stage and the finish area being noisily dismantled by members of the Tour’s vast travelling army of workers, Brailsford sits in a bar and reviews the day. While his companions drink beer, he orders mineral water. ‘I’m in training,’ he explains. ‘I’m riding l’Etape du Tour [a stage of the Tour, the popular mass participation ride] with Shane.’

Until now, Brailsford, though he has become a familiar figure at track cycling events, has not been a regular visitor to the Tour de France. But there’s a good reason for that: it falls outside his remit. Three years earlier he had inherited the track-focused programme, known as the World Class Performance Plan, devised by his predecessor, Peter Keen. As Brailsford sits down in Bourg-en-Bresse he can reflect that Keen’s World Class Performance Plan is exactly a decade old; what he cannot see, other than in his wildest dreams, is that in 13 months it will come to glorious fruition at the Beijing Olympics.