Полная версия:

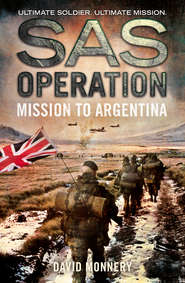

Mission to Argentina

Mission to Argentina

DAVID MONNERY

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by 22 Books/Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1994

Copyright © Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1994

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Cover Photographs © IWM/Getty Images (main image); STF/Staff/Getty Images (planes); Shutterstock.com (textures)

David Monnery asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008155094

Ebook Edition © December 2015 ISBN: 978008155100

Version: 2015-11-02

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Epilogue

OTHER TITLES IN THE SAS OPERATION SERIES

About the Publisher

1

There had not been a silence so complete in the public bar of the Slug & Sporran since Rangers won an ‘Old Firm’ match at Parkhead in injury time. Every head in the bar was turned towards the TV, and every right arm seemed suspended between mat and mouth with its cargo of beer. On the screen the aircraft carrier Invincible was moving slowly out towards the Portsmouth harbour entrance, past quaysides lined with cheering, weeping, laughing, flag-waving crowds. The British were not just going to war; they were going in style.

James Keir Docherty could hardly believe any of it. He could not believe such rapt attention from a bar more used to toasting the IRA than the English overlord; he could not believe the Government was actually standing up to the Argentinian generals; and he could not believe his unit, B Squadron, 22 SAS Regiment, had merely been placed on permanent standby. Those lucky bastards from D Squadron were already on their way to Ascension Island, with G Squadron next in the queue.

At this moment in his life Docherty was even more disposed to military adventure than usual. A couple of miles away to the south, in one of the developments built on the grave of the Gorbals, his father was slowly dying of emphysema. And it looked like the old bastard was intent on taking with him any last chance of a meeting of minds between father and son.

Docherty was not needed at the bedside, that was for sure. His mother, his two sisters, half the block, probably half the city’s trade-union officials, were all already there, drinking tea, swapping yarns, reliving the glorious defeats of the past. His father would be a candidate for best-loved man in the city, Docherty thought sourly. He would leave this earth on a river of good will, arrive at the heavenly gates with enough testimonials from the rank and file to make even St Peter feel inadequate.

He took the penultimate swig from his pint. The ships were still sailing out of the harbour, the crowds still waving. Every now and then the cameramen would find a particularly sexy-looking woman to zoom in on. Several seemed to be waving their knickers round their heads. Sex and death, Docherty thought.

He sighed, remembering those weeks on the beach at Zipolite, both bowed down by grief and lifted up by…by just sun and sea really, by the wonder of the ordinary. The best decision he had ever made, buying that air ticket; one of the few he had not regretted. ‘My life’s a fucking mess,’ he murmured into his glass. A dead wife, a dying father, and he could not come to terms with either of them. Why the fuck hadn’t they called up B Squadron?

Should he have another drink? No – getting pissed in the afternoon was never a good idea. Getting pissed alone was never a good idea. He drained the glass and got to his feet.

Brennan Street was wreathed in sunshine. A good-looking girl walking down the opposite pavement – long legs in black tights and big silver earrings dancing in dark red hair – reminded him how long it had been since he had had a woman. It was almost two years since his self-appointed mission to screw every whore in Glasgow had fizzled out in the near-bankruptcy of both pocket and soul.

It would be a while longer before he broke his fast, Docherty decided. He grinned to himself. He would go and see Liam McCall instead. After all, what else was religion but a substitute for sex?

He walked down Brennan Street, cut across Sauchiehall Street, and worked his way through the back streets to the Clyde. Every time he came back to Glasgow he was surprised by the speed with which it seemed to be changing, and mostly for the better. Sure, the shipyards were almost a memory, but new businesses seemed to be springing up everywhere, along with new eating places and theatres and galleries and leisure centres. There seemed to be so much more for young people to do than there had been when he was a boy.

But it was not all good news. The Gorbals of his youth – ‘a jungle with a heart of gold’ as one wit had named it – had simply been wiped away, and replaced by a desert. One without even the pretence of a heart of gold.

And unemployment was still going up and up, despite all the new businesses. If he had taken his father’s advice when he was sixteen he would be on the scrap heap by now, a thirty-one-year-old with skills no one wanted any more. But would his father ever admit that? Not till fucking doomsday, he wouldn’t. Joining the Merchant Navy had been irresponsible, joining the Army something close to treason, getting into the SAS about as kosher as screwing Margaret Thatcher and enjoying it.

Why did he care what his father thought? Why was he in Glasgow when he could be enjoying himself at any one of a hundred other places in Britain? He knew he had made good decisions. His life was a fucking mess despite them, not because of them.

He crossed the river. At least he was in good physical shape, no matter what the state of his psyche might be. A couple of drunks were happily throwing up on the bank below. Two leather-jacketed teenagers with outrageously greased quiffs were watching them from the bridge and laughing. They had empty Chinese food cartons all around them, probably bought with the spoils of a mugging. A walk across Glasgow in the early hours of Sunday morning might be a good SAS training exercise, Docherty thought. Requiring stamina, unarmed combat skills and eyes in the back of your head. Not to mention a sense of humour.

Another couple of miles brought him to his friend’s parish church, which stood out among its high-rise surroundings rather like the Aztec pyramid Docherty had seen half-excavated on the edge of Mexico City’s central square. Father McCall, whom even the schoolkids simply called ‘Liam’, was standing on the pavement outside, apparently lost in thought. He looked older, Docherty thought. He was nearly sixty now, and his had not exactly been a life of ease.

‘Hello, Liam,’ he said.

The frocked figure turned round. ‘Jamie!’ he exclaimed. The eyes still had their sparkle. ‘How long have you been back? I thought you’d be gone, you know, on duty or whatever you call it.’

‘Duty will do. But no. No such luck. There aren’t enough ships to transport all the men who want to go. I’m on twenty-four-hour standby, but…’ He shrugged and then grinned. ‘It’s good to see you, Liam. How are you? How are things here?’

‘Much the same. Much the same.’ The priest stared out across the city towards the distant Campsie Fells, then suddenly laughed. ‘You know, I was thinking just now – I think I’m beginning to turn into a Buddhist. So much of what we see as change is mere chaff, completely superficial. And deep down, things don’t seem to change at all. Of course,’ he added with a quick smile, ‘as a Catholic I believe in the possibility of redemption.’

Docherty smiled back at him. He had known the priest since he was about five years old. Liam would have been in his early thirties then, and the two of them had begun a conversation which, though sometimes interrupted for years on end, had continued ever since – and seemed likely to do so until one of them died.

‘Do you have time for a walk round the park?’ Docherty asked.

Liam looked at his watch. ‘I have a meeting in an hour or so…so, yes. And you didn’t answer my question. How long have you been here?’

‘I didn’t answer it because I felt guilty. I’ve been here almost a week. My father’s dying and…well, I always seem to end up dumping all my problems on you, and, you know, every once in a while I get this crazy idea of trying to sort them out for myself.’

Liam grunted. ‘Crazy is about right. Are you trying to put me out of business? How long would the Church last if people started sorting out their own problems?’

Docherty grinned. ‘OK, I get the message. You…’ He broke off as a football came towards them, skidding across the damp grass. The priest trapped the ball in one motion, and sent it back, hard and accurately, with a graceful swing of the right leg. ‘Nice one,’ Docherty said. Maybe his friend was not getting old just yet.

‘You know, it’s a frightening thought,’ Liam said, ‘but I’m afraid I shall still be trying to kick pebbles into imaginary goals when I can barely walk.’

‘Makes you wonder what sort of God would restrict your best footballing years to such an early part of life,’ Docherty observed.

‘Yes, it does,’ the priest agreed. ‘I’m sorry about your father,’ he went on, as if the subject had not changed. ‘Of course, I knew he was seriously ill…Is there no hope?’

‘None. It’s just a matter of time.’

‘That’s true for all of us.’

‘It’s a matter of weeks, then. Maybe even days.’

‘Hmmm. It must be very painful for you.’

‘Not as painful as it is for him.’

Liam gave him a reproachful glance. ‘You know what I mean.’

‘Aye. I’m sorry. And yes, it is painful. He’s dying and I don’t know how to deal with it. I don’t know how to deal with him. I never have.’

‘I know. But I have to say, and I’ve said it to you often enough in the past: I think he must carry more of the blame for this than you…’

Docherty scratched his ear and smiled ruefully. ‘Maybe. Maybe. But…’

‘Everybody loves him. Campbell Docherty, the man who’d do anything for anyone, who worked a twenty-hour day for the union, who’d give his last biscuit to a stray dog. One of our secular saints. He loves everybody and everybody loves him.’

‘Except me.’

‘There was no room for you, no time. Or maybe he just couldn’t cope with another male in the family circle. It’s common enough, Jamie. Glasgow’s full of boys sleeping rough because their fathers can’t cope with living with a younger version of themselves.’

‘I know. I agree. But what do I do? It’s nuts that I let myself get so wound up by this, I know it is…’

‘I don’t think so, Jamie. Fathers and sons have been trying to work each other out since the beginning of time. It’s just something they do…’

Docherty shook his head. ‘You know, every time I come back here I feel like I’m returning to the scene of the crime.’

‘There’s no crime. Only family.’

Docherty could not help laughing. ‘Nice one, Liam.’

‘Do you talk to him like you talk to me?’ the priest asked.

‘I try to. He even agrees with me, but nothing changes.’

‘Maybe this time.’

‘Maybe. There won’t be many others.’

They walked in silence for a while. The dusk was settling over the park, reminding Docherty of all those evenings playing football as a kid, with the ball getting harder and harder to see in the gloom. ‘Sometimes, these days, I feel like an old man,’ he said. ‘Not in body, but in soul.’

‘Think yourself lucky it’s only your soul, then,’ Liam observed. ‘It only needs one dark cloud coming in from the West, and every joint in me starts aching.’

‘I’m serious,’ Docherty insisted.

‘So am I. But I know what you mean. You live too much in the past, Jamie…’

‘I know. I can’t seem to shake it, though. You know’ – he stopped underneath a budding tree – ‘there are two scenes which often come into my head when I’m not thinking – like they’re always there, but most of the time they’re overlaid by something more immediate. One is our parlour when I was a small kid. I must have been about six, because Rosie is still crawling around and Sylvia is helping Mum with the cooking, and Dad’s sitting there at the table with a pile of work talking to one of the shop stewards, and I’m doing a jigsaw of the Coronation Scot. Remember, that blue streamliner? Nothing ever happens in this scene; it’s just the way things are. It feels really peaceful. There’s a kind of contentment which oozes out of it.’

‘I remember that room,’ the priest replied.

‘The other scene is a style on a path up near Morar, for Christ’s sake. I’m just reaching up to help Chrissie down, and she looks down at me with such a look of love I can hardly keep the tears in. Just that one moment. It’s almost like a photograph, except for the changing expression on her face. It was only a couple of weeks later that she was killed.’

Liam said nothing – just put his hand on Docherty’s arm.

‘It’s weird,’ Docherty went on. ‘I’ve seen some terrible things as a soldier. Oman was bad enough, but believe me, you won’t find a crueller place than Belfast. I got used to it, I suppose. You have to if you’re going to function. But sometimes I don’t think I’ll ever get over that room or that woman.’ He turned to face the priest, smiling wryly. ‘I couldn’t tell this sort of thing to anyone but you,’ he said.

‘Most people couldn’t tell it to anyone at all,’ Liam said. ‘You underestimate yourself. You always have. But I don’t think you should put these two scenes of yours together. I think you will get over Chrissie, even if it takes another ten years. But that room of yours – it sounds almost too good to be true, you know what I mean? Like a picture of the world the way we want it to be, everyone in their proper place, living in perfect harmony…’

‘Yeah. And what’s even crazier: I know it wasn’t really like that most of the time.’

‘That doesn’t matter. It can still be a good picture for someone to hold in their head. Particularly a soldier.’

‘How did you get to be so wise?’ Docherty asked him with a smile.

‘Constant practice. And I still feel more ignorant every day.’

‘Don’t the Buddhists think that’s a sign of wisdom?’

‘Yes, but I have to beware the sin of pride where my ignorance is concerned.’

Docherty grinned. ‘I think you’re probably the most ignorant man I’ve ever met,’ he said. ‘And your time is up.’

The priest looked at his watch. ‘So it is. I…’

‘I’ll drop by again tomorrow or the next day,’ Docherty said. ‘Maybe we can get to a game while I’m up here.’

They embraced in the gloom, and then Liam hurried back across the park. Docherty watched him go, thinking he detected a slowing of the priest’s stride as he passed the kids playing football. But this time no ball came his way.

Docherty turned and began walking slowly in the direction of his parents’ flat, thinking about the conversation he had just had, wondering how he could turn it into words for his father when the time came. Half the street lights seemed to be out in Bruce Street, and the blocks of flats had the air of prison buildings looming out of the rapidly darkening sky. Groups of youths seemed to cling to street corners, but there were no threatening movements, not even a verbal challenge. Either his walk was too purposeful to mistake, or here, on his home turf, they recognized Campbell Docherty’s boy, ‘the SAS man’.

His sister’s face at the door told him more than he wanted to know. ‘Where have you been?’ she said through the tears. ‘Dad died this afternoon.’

She was frightened for the first few minutes. The whole situation – sitting beside him in the back seat, her hands clasped together in her lap, watching the traffic over the driver’s shoulder – seemed so reminiscent of those few hours that had devastated her life seven years before.

But this was London, not Buenos Aires, and the policeman beside her – if that was what he was – had treated her with what she had come to know as the British version of nominal respect. He had not leered at her in the knowledge that she was the next piece of meat on his slab.

That day it had been raining, great sheets of rain and puddles big as lakes on the Calle San Martín. And Francisco had been with her. For the very last time. She could see his defiant smile as they dragged him out of the car.

Stop it, she told herself. It serves no purpose. Live in the present.

She brought the crowded pavements back into focus. They were in Regent Street, going south. It was not long after three o’clock on a sunny spring afternoon. There was nothing to worry about. Her arrest – or, as they put it, ‘request for an interview’ – was doubtless the result of some bureaucratic over-reaction to the Junta’s occupation of the Malvinas the previous Friday. Probably every Argentinian citizen in England was being offered an interview he or she could not refuse.

A vague memory of a film about the internment of Japanese living in America in 1941 flickered across her mind. Were all her fellow compatriots about to be locked up? It did not seem likely: the English were always complaining that their prisons were too full already.

Today was the day their fleet was supposed to sail. A faint smile crossed her face, partly at the ridiculousness of such a thing in 1982, partly because she knew how appalled the Junta would be at the prospect of any real opposition. The idiots must have thought the English would just shout and scream and do nothing, or they would never have dared to take the islands. Or they had not bothered to think at all, which seemed even more likely.

It was all a little hard to believe. The shoppers, the late-lunching office workers, the tourists gathered round Eros – it looked much the same as any other day.

‘We’re almost there,’ the man beside her said, as much to himself as to her. The car pulled through Admiralty Arch, took a left turn into Horse Guards Road, and eventually drew to a halt in one of the small streets between Victoria Street and Birdcage Walk. Her escort held the car door for her, and wordlessly ushered her up a short flight of steps and into a Victorian house. ‘Straight on through,’ he murmured. A corridor led through to a surprisingly large yard, across the far side of which were ranged a line of two-storey Portakabins.

‘So this is where M hangs out,’ she murmured to herself in Spanish.

Inside it was all gleaming white paintwork and ferns from Marks & Spencer. A secretary who looked nothing like Miss Moneypenny gestured her into a seat. She obliged, wondering why it was the English ever bothered to speak at all. It was one of the things she had most missed, right from the beginning: the constant rattle of conversation, the noise of life. Michael had put it all down to climate – lots of sunshine led to a street-café culture, which encouraged the art of conversation. Drizzle, on the other hand, was a friend of silence.

She preferred to think the English were just repressed.

A door slammed somewhere, and she saw a young man walking away across the yard. He looked familiar – a fellow exile, she guessed. In one door and out another, just in case the Argies had the temerity to talk to each other. She felt anger rising in her throat.

‘Isabel Fuentes?’ a male voice asked from the doorway leading into the next office.

‘Sí?’ she said coldly.

‘This way, please.’

She walked through and took another offered seat, across the desk from the Englishman. He was not much older than her – early thirties, she guessed – with fair hair just beginning to thin around the temples, tired blue eyes and a rather fine jawline. He looked like he had been working for days.

The file in front of him had her name on it.

He opened it, examined the photograph and then her. Her black hair, cropped militantly short in the picture, was now past her shoulder, but she imagined the frown on her face was pretty much the same. ‘It is me,’ she said helpfully.

He actually smiled. ‘Thank you for coming,’ he said.

‘I was not conscious of any choice in the matter.’

He scratched his head. ‘It’s a grey area,’ he admitted, ‘but…’ He let the thought process die. ‘I would like to just check some of the details we have here…’ He looked up for acquiescence.

She nodded.

‘You came to the UK in July 1975, and were granted political asylum in September of the same year…that was quick,’ he interrupted himself, glancing up at her again.

‘It didn’t seem so,’ she said, though she knew her father’s money had somehow smoothed the path for her. She had friends and acquaintances who were still, seven years later, living in fear of being sent back to the torturers.

He grunted and moved on. ‘Since your arrival you have completed a further degree at the London School of Economics and had a succession of jobs, all of which you have left voluntarily.’ He glanced up at her, as if in wonderment at someone who could happily throw jobs away in such difficult times. ‘I presume you have a private source of income from your parents?’

‘Not any more.’ Her father had died four years ago, and her mother had cut all contact since marrying some high-ranking naval bureaucrat. ‘I live within my means,’ she said curtly.

He shrugged. ‘Currently you have two part-time jobs, one with a travel agency specializing in Latin-American destinations, the other in an Italian restaurant in Islington.’

‘Yes.’

‘Before you left Argentina you were an active member of the ERP – the Popular Revolutionary Army, correct? – from October 1973 until the time of your departure from Argentina. You admitted being involved in two kidnappings and one bank robbery.’

‘“Admitted” sounds like a confession of guilt. I did not feel guilty.’

‘Of course…’ he said patiently.

‘It is a grey area, perhaps,’ she said.

He smiled again. ‘You are not on trial here,’ he said. ‘Now, am I correct in thinking that the ERP was a group with internationalist leanings, unlike those who regarded themselves as nationalist Peronistas?’

‘You have done your homework well,’ she said, wondering what all this could be leading to. ‘I suppose it would do no good to ask who I am talking to?’