Полная версия:

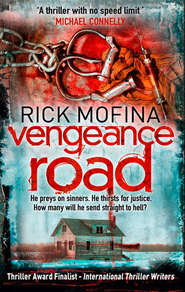

Vengeance Road

Praise for

RICK MOFINA

“A lightning-paced thriller with lean, tense writing … Mofina really knows how to make the story fly.”

—Tess Gerritsen, New York Times bestselling author on A Perfect Grave

“At full-throttle from the first page and doesn’t let up till the last.”

—Linwood Barclay on Every Fear

“A snappy action-packed, hard-to-put-down thriller.”

—Daily Mail on The Dying Hour

“Rick Mofina keeps you turning the pages with characters you care about, a believable plot and as many twists as it takes to keep the suspense at a high level until the shattering conclusion.”

—Peter Robinson on The Dying Hour

“It moves like a tornado”

—James Patterson on Six Seconds

“Grabs your gut—and your heart—in the opening scenes and never lets go.”

—Jeffery Deaver on Six Seconds

“Classic virtues but tomorrow’s subjects—everything we need from a great thriller.”

—Lee Child on Six Seconds

Also by Rick Mofina

SIX SECONDS

Jason Wade novels

THE DYING HOUR

EVERY FEAR

PERFECT GRAVE

A Jack Gannon novel

VENGEANCE ROAD

Coming soon from MIRA books

THE PANIC ZONE

vengeance

road

RICK MOFINA

www.mirabooks.co.uk

This book is for Barbara

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you, Amy Moore-Benson

My thanks to the New York State Police.

Thank you to Valerie Gray, Dianne Moggy, Catherine Burke and the excellent editorial, marketing, sales and PR teams at MIRA Books. As always, I am indebted to Wendy Dudley. I also thank my friends in the news business for their help and support; in particular, Sheldon Alberts, Washington Bureau Chief for CanWest News Service, Glen Miller, Metro, Juliet Williams, Associated Press, Sacramento, California, Bruce DeSilva and Vinnee Tong, Associated Press, New York. Also Lou Clancy, Eric Dawson, Jamie Portman, Mike Gillespie, colleagues past and present with the Calgary Herald, Ottawa Citizen, CanWest News, Canadian Press, Reuters, the Toronto Star, Globe and Mail and so many others.

You know who you are.

Thanks to Ginnie Roeglin, Tod Jones, David Fuller, Steve Fisher, Lorelle Gilpin, Sue Knowles, David Wright and everyone at The C.C. I am grateful to Pennie Clark Ianniciello, Shana Rawers, Wendi Wambolt and Melissa McMeekin.

Very special thanks to Laura and Michael.

Again, I am indebted to sales representatives, booksellers and librarians for putting my work in your hands. Which brings me to you, the reader—the most critical part of the entire enterprise.

Thank you very much for your time, for without you, a book remains an untold tale. I hope you enjoyed the ride and will check out my earlier books while watching for my next one. I welcome your feedback. Drop by at www.rickmofina.com, subscribe to my newsletter and send me a note.

I am the man that hath seen affliction

by the rod of his wrath.

He hath led me, and brought me into

darkness, but not into light.

Surely against me is he turned; he turneth

his hand against me all the day.

—Lamentations 3:1–3

The evil that men do lives after them;

The good is oft interred with their bones.

—William Shakespeare

Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene ii

1

The taxi crawled along a road that knifed into the night at Buffalo’s eastern edge.

Its brakes squeaked as it halted at the fringe of a vast park.

Jolene Peller gazed toward the woods then paid the driver.

“This is where you want to be dropped off?” he asked.

“Yes. Can you kill the meter and wait for me, please?”

“I can’t, you’re my last fare. Gotta get the cab back.”

“Please, I just have to find my friend.”

The driver handed her a five in change, nodding to the pathway that twisted into darkness beyond the reach of his headlights.

“You’re sure your friend’s down there?”

“Yes, I need to get her home. She’s going through a rough time.”

“It’s a beautiful park, but you know what some people do down there at night?”

Jolene knew.

But she was living another life then. If you could call it living.

“Can’t you wait a bit?” Jolene asked.

“Not on my time. Gotta get the cab back then start my vacation.”

“Please.”

“Look, miss, you seem nice. I’ll take you back now. I’ll give you a break on the fare because it’s on my way. But I ain’t waitin’ while you wander around looking for your problem. Stay or go? What’s it going to be?”

Tonight was all Jolene had to do the right thing.

“I have to stay,” she said.

The driver gave her a suit-yourself shrug and Jolene got out. The taxi lumbered off, its red taillights disappearing, leaving her alone.

She had to do this.

As she walked along the path, she looked at the familiar twinkle of lights from the big suburban homes on the ridge that ringed the parkland half a mile off. When she found Bernice, they’d walk to a corner store then get a cab to Bernice’s apartment. Then Jolene could take another one to the terminal, claim her bags and catch a later bus.

But not before she found Bernice.

Not before she saved her.

And tonight, for one brief moment, she thought she had.

Less than an hour ago they were together in a downtown diner where Jolene had pleaded with her.

“Honey, you’ve got to stop beating yourself up for things that were never your fault.”

Tears rolled down Bernice’s face.

“You’ve got to get yourself clean and finish college.”

“It’s hard, Jo. So hard.”

“I know, but you’ve got to pull yourself out of the life. If I can do it, you can do it. Promise me, right here, right now, that you won’t go out tonight.”

“It hurts. I ache. I need something to get me through one more day. I need the money. I’ll start after tomorrow.”

“No!”

A few people cast sleepy glances at them. Jolene lowered her voice.

“That’s a lie you keep telling yourself. Promise me you won’t go dating tonight, that you will go home.”

“But it hurts.”

Jolene seized Bernice’s hands, entwined their fingers and squeezed hard.

“You’ve got to do this, honey. You can’t accept this life. Promise me you will go home. Promise me, before I get on my bus and leave town.”

“Okay, I promise, Jo.”

“Swear.”

“I swear, Jo.”

Jolene hugged her tight.

But after getting into her taxi and traveling several blocks, Jolene was uncertain. She told the driver to go back so she could check on Bernice.

Sure enough, there she was. At the mouth of a dirty alley, on Niagara, hustling a date. The cab stopped at a light, Jolene gripped her door handle, bracing to jump out and haul Bernice off the street.

But she didn’t.

To hell with that girl.

Jolene told the driver to keep going to the terminal. She didn’t need this shit. Not now. She was leaving for Florida tonight to build a new life for herself and her little boy. Bernice was an adult, old enough to take care of herself.

Jolene had tried to help.

She really had.

But with each passing block, her guilt grew. Soon the neon blurred. Brushing away her tears, Jolene cursed. She couldn’t leave Buffalo tonight with that last image of her friend standing in her memory.

Bernice was an addict. She was sick. She needed help. Jolene was her lifeline.

And tonight, every instinct told Jolene that something was wrong.

The driver muttered when she requested he take her back to the alley. But by the time they’d returned, Bernice and the man she’d been hustling were gone.

Jolene had a bad feeling.

But she knew exactly where they’d be.

Down here, by the creek.

Funny, Jolene thought, during the day this was a middle-class sanctuary where people walked, jogged, even took wedding pictures near the water.

And dreamed.

Most locals, living their happy lives, were unaware that after dark, their park was where hookers took their dates.

It was where you left the real world; where you buried your dignity; where each time you used your body to survive, a piece of you died.

Jolene knew it from her former life; the life she’d escaped when she had Cody. He was her number-one reason for getting out. She’d vowed he would not have a junkie mother selling herself for dope.

He deserved better.

So did Bernice.

She’d been abandoned, abused, but had worked so hard to get into college, only to face a setback that led to drugs, which pushed her here. The tragedy of it was that she was only months away from becoming a certified nurse’s aide.

Bernice didn’t belong in this life.

Date or no date, Jolene was going to find her and drag her ass home, if it was the last thing she did. Jolene was not afraid to come down here at night. She knew the area and knew how to handle herself.

She had her pepper spray.

She arrived at the dirt parking lot, part of an old earthen service road that bordered the pathway meandering alongside the creek. The lot was empty.

No sign of anybody.

As crickets chirped, Jolene took stock of the area and the treetops silhouetted against a three-quarter moon. She knew the hidden paths and meadows, where drugs and dates were taken and deals completed.

Through a grove, she saw a glint of chrome, like a grille from a vehicle parked in a far-off lot. Possibly a truck. Jolene headed that way. She was nearly there when a scream stopped her cold.

“Nooo! Oh God nooo! Help me!”

The tiny hairs on the back of Jolene’s neck stood up.

Bernice!

Her cry came from the darkest section of the forest near the creek. Jolene rushed to it. Branches slapped at her face, tugged at her clothing.

The growth was thicker than she’d remembered. Her eyes had not adjusted; she was running blind over the undulating terrain.

She stepped on nothing and the ground rose to smack her.

She scrambled to her feet and kept going.

There was movement ahead, shadow play in the moonlight.

Noises.

Jolene didn’t make a sound as she reached into her bag, her fingers wrapping around her pepper spray.

A blast to the creep’s face. A kick in the groin. Jolene had done it before with freaks who’d tried to choke her.

She swallowed hard, ready to fight. Heart pumping, she strained to see what awaited her. Someone was moving; she glimpsed a figure.

Bernice? Was that her face in the ground?

A metallic clank.

Tools? What was going on?

The air exploded next to Jolene with a flap and flutter of a terrified bird screeching to the sky. Startled, Jolene stepped away and fell, crashing through a dried thicket.

She was unhurt.

The air was dead still.

A figure was listening.

Jolene froze.

The figure was thinking.

Her blood thundered in her ears.

A twig snapped. The figure was approaching.

She held her breath.

It was getting closer.

All of her senses were screaming.

Her fingers probed the earth but she was unable to find her bag. Frantic, she clawed the dirt for her pepper spray, a rock, a branch.

Anything.

Her pulse galloped, she didn’t breathe. After several agonizing moments, everything subsided. The threat seemed to pass with a sudden gust that rustled the treetops.

Oh, thank God.

Jolene collected herself to resume looking for Bernice, when she was hit square in the face by a blazing light.

Squinting, she raised her hands against the intensity. Someone grunted, a shadow strobed. She ran but fireworks exploded in her head, hurling her into nothingness.

2

What was that?

The next morning, Jack Gannon, a reporter at the Buffalo Sentinel, picked up a trace of tension on the paper’s emergency scanners.

An array of them chattered at the police desk across the newsroom from where he sat.

Sounds like something’s going on in a park, he thought as a burst of coded dispatches echoed in the quiet of the empty metro section.

Not many reporters were in yet.

Gannon was not on cop-desk duty today, but he’d cut his teeth there years ago, chasing fires, murders and everyday tragedies. It left him with the skill to pluck a key piece of data from the chaotic cross talk squawking from metro Buffalo’s police, fire and paramedic agencies.

Like a hint of stress in a dispatcher’s voice, he thought as he picked out another partial transmission.

Somebody had just called for the medical examiner.

The reporter on scanner duty better know about this.

For the last two weeks the assignment desk had promised to keep Gannon free to chase a tip he’d had on a possible Buffalo link to a woman missing from New England.

He needed a good story.

But this business with the police radios troubled him.

Scanners were the lifeblood of a newspaper. And no reporter worth a damn risked missing something that a competitor might catch, especially in these days of melting advertising and shrinking circulation.

Did anyone know about this call for the medical examiner?

He glanced over his computer monitor toward the police desk at the far side of the newsroom, unable to tell who, if anyone, was listening.

“Jeff!” He called to the news assistant but got no response.

Gannon walked across the newsroom, which took up the north side of the fourteenth floor and looked out to Lake Erie.

The place was empty, a portrait of a dying industry, he thought.

A couple of bored Web-edition editors worked at desks cluttered with notebooks, coffee cups and assorted crap. A bank of flat-screen TV monitors tilted down from the ceiling. The sets were tuned to news channels with the volume turned low.

Gannon saw nothing on any police activity anywhere.

He stopped cold at the cop desk.

“What the hell’s this?”

No one was there listening to the radios.

Doesn’t anyone give a damn about news anymore? This is how we get beat on stories.

He did duty here last week. This week it was someone else’s job.

“Jeff!” he shouted to the news assistant who was proofreading something on his monitor. “Who’s on the scanners this morning?”

“Carson. He’s up at the Falls. Thought a kid had gone over but turns out he dropped his jacket in the river. Carson blew a tire on his way back here.”

“Who’s backing him up?” Gannon asked.

“Sharon Langford. I think she went to have coffee with a source.”

“Langford? She hates cop stories.”

Just then one of the radios carried a transmission from the same dispatcher who’d concerned Gannon.

“… copy … they’re rolling to Ellicott and the park now … ten-four.”

Calling in the M.E. means you have a death. It could be natural, a jogger suffering a heart attack. It could be accidental, like a drowning.

Or it could be a homicide.

Gannon reached down, tried to lock on the frequency but was too late. He cursed, returned to his desk, kicked into his old crime-reporter mode, called Buffalo PD and pressed for information on Ellicott.

“I got nothing for you,” the officer said.

All right. Let’s try Cheektowaga.

“We got people there but it’s not our lead.” The officer refused to elaborate.

How about Amherst PD?

“We’ve got nothing. Zip.”

This thing must have fallen into a jurisdictional gray zone, he thought as he called Ascension Park PD.

“We’re supporting out there.”

Supporting? He had something.

“What’s going on?”

“That’s all I know. Did you try ECSO?” said the woman who answered for Ascension Park.

A deputy with the Erie County Sheriff’s Office said, “Yeah, we’ve got people there, but the SP is your best bet.”

He called the New York State Police at Clarence Barracks. Trooper Felton answered but put him on hold, thrusting Gannon into Bruce Springsteen’s “The River.”

Listening to the song, Gannon considered the faded news clippings pinned to low walls around his desk, his best stories, and the dream he’d pretty much buried.

He never made it to New York City.

Here he was, still working in Buffalo.

The line clicked, cutting Springsteen off.

“Sorry,” Felton said, “you’re calling from the Sentinel about Ellicott Creek?”

“Yes. What do you have going on out there?”

“We’re investigating the discovery of a body.”

“Do you have a homicide?”

“Too soon to say.”

“Is it a male or female? Do you have an ID, or an age?”

“Cool your jets there. You’re the first to call. Our homicide guys are there, but that’s routine. I got nothing more to release yet.”

“Who made the find?”

“Buddy, I’ve got to go.”

A body in Ellicott. That was a nice area.

He had to check it out.

He tucked his notebook into the rear pocket of his jeans and grabbed his jacket, glancing at the senior editors in the morning story meeting in the glass-walled room at the far west side.

Likely discussing pensions, rather than stories.

“Jeff, tell the desk I’m heading to Ellicott Creek.” He tore a page from his notebook with the location mapped out. “Get a shooter rolling to this spot. We may have a homicide.”

And I may have a story.

3

Gannon hurried to the Sentinel’s parking lot and his car, a used Pontiac Vibe, with a chipped windshield and a dented rear fender.

The paper was downtown near Scott and Washington, not far from the arena where the Sabres played. The fastest way to the scene was the Niagara leg of the New York State Thruway to 90 north.

Wheeling out, with Springsteen in his head, Gannon questioned where he was going with his life. He was thirty-four, single and had spent the last ten years at the Buffalo Sentinel.

He looked out at the city, his city.

And there was no escaping it.

Ever since he was a kid, all he wanted to be was a reporter, a reporter in New York City. And it almost happened a while back after he broke a huge story behind a jetliner’s crash into Lake Erie.

It earned him a Pulitzer nomination and job offers in Manhattan.

But he didn’t win the prize and the offers evaporated.

Now it looked like he’d never get to New York. Maybe this reporter thing wasn’t meant to be? Maybe he should do something else?

No way.

Being a reporter was written in his DNA.

One more year.

He remembered the ultimatum he’d given himself at the funeral.

One more year to land a reporting job in New York City.

Or what?

He didn’t know, because this stupid dream was all he had. His mother was dead. His father was dead. His sister was—well, she was gone. His ultimatum kept him going. The ultimatum he’d given himself after they’d lowered his parents’ caskets into the ground eleven months ago.

Time was running out.

Who knows? Maybe the story he needed was right here, he told himself while navigating his way closer to the scene, near Ellicott Creek.

It was on the fringes of a lush park.

Flashing emergency lights splashed the trees in blood red as he pulled up to a knot of police vehicles.

Uniformed officers were clustered at the tape. Gannon saw nothing beyond them but dense forest, as a stone-faced officer eyed his ID tag then assessed him.

“It’s way in there. There’s no chance you media maggots are getting any pictures of anything today.”

The others snickered.

Gannon shrugged it off. He’d been to more homicides than this asshole. Besides, guys like that never deterred him. If anything, he thought, tapping his notebook to his thigh, they made him better.

All right, pal, if there’s a story here, I’m going to find it.

After some thirty minutes of watching detectives in suits, and forensics people in overalls, walk in and out of the forest, Gannon was able to buttonhole a state police investigator with a clipboard heading to his unmarked sedan.

“Hey, Jack Gannon from the Buffalo Sentinel. Are you the lead?”

“No, just helping out.”

“What do you have?”

Gannon stole a glimpse of the data on his clipboard. Looked like statements.

“We’re going to put out a release later,” the investigator said.

“Can you give me a little information now?”

“We don’t have much, just basics.”

“I’ll take anything.”

“A couple of walkers discovered a female body this morning.”

“Is it a homicide?”

“Looks that way.”

“What age and race is the victim?” Gannon asked.

“I’d put her in her twenties. White or Native American. Not sure.”

“Got an ID?”

“Not confirmed. We need an autopsy for that.”

“Can I talk to the walkers?”

“No, they went home. It was a disturbing scene.”

“Disturbing? How?”

“I can’t say any more. Look, I’m not the lead.”

“Can I get your name, or card?”

“No, no, I don’t want to be quoted.”

That was all Gannon could get and he phoned it in for the Web edition, putting “disturbing scene” in his lead. In the time that followed, more news teams arrived and Lee Watson, a Sentinel news photographer, called Gannon’s cell phone sounding distant against a drone.

“What’s up, are you in a blender, Lee?” Gannon asked.

“I’m in a rented Cessna. The paper wants an aerial shot of the scene.”

Gannon looked up at the small plane.

“Watch for Brandy Somebody looking for you,” Watson said. “She’s the freelancer they’re sending to shoot the ground. Point out anything for her.”

When Brandy McCoy, a gum-snapping freelancer, arrived, the first thing Gannon did was lead her from the press pack and cops at the tape to the unmarked car belonging to the investigator he’d talked to earlier.

The detective had gone back into the woods. His car was empty, except for his clipboard on the passenger seat. Gannon checked to ensure no one could see what he and the photographer were doing.

“Zoom in and shoot the pages on the clipboard. I need the information.”

“Sure.”

Brandy’s jaw worked hard on bubble gum as she shot a few frames then showed Gannon.

“Good,” he said, jotting information down and leaving. “My car’s over here, come on.”

Twenty minutes later, Gannon and Brandy were walking to the front door of the upscale colonial house of Helen Dodd. She was a real estate broker, and her friend, Kim Landon, owned an art gallery in Williamsville, according to the information Gannon had gleaned from the police statements.