Полная версия:

The Buried Circle

THE

BURIED

CIRCLE

Jenni Mills

In memory of my father, Robert Mills, who flew

1916-78

and my mother, Sheila Mills, who danced

1921-2007

I sought for ghosts and sped

Through many a listening chamber, cave and ruin,

And starlight wood, with fearful steps pursuing

Hopes of high talk with the departed dead.

Percy Bysshe Shelley,

Hymn To Intellectual Beauty

Time wounds all heels.

Groucho Marx, John Lennon,

and others, including Margaret Robinson

Table of Contents

Part One-Memory Crystals

Chapter 1 - Lammas, 2005

Chapter 2 - Autumn Equinox

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Part Two - Imbolc

Chapter 5 - Candlemas

Chapter 6 - 1938

Chapter 7

Chapter 8 - 1938

Chapter 9

Chapter 10 - 1938

Chapter 11

Part Three - Equal Night

Chapter 12 - 1938

Chapter 13

Chapter 14 - 1938

Chapter 15

Chapter 16 - 1938

Chapter 17

Chapter 18 - 1938

Chapter 19

Chapter 20 - 1938

Chapter 21

Chapter 22 - 1938

Chapter 23

Chapter 24 - September 1938

Part Four - Fire Festival

Chapter 25 - 1939

Chapter 26

Chapter 27 - 1940–1941

Chapter 28

Part Five - Earth Magic

Chapter 29 - 1941

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32 - 1941

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37 - 1941

Chapter 38

Chapter 39 - 1941–2

Part Six - The Sun Stands Still

Chapter 40 - 1942

Chapter 41 - Solstice

Chapter 42 - 1942

Chapter 43 - 1942

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Part Seven - Killing Moon

Chapter 47 - 29 August 1942

Chapter 48

Chapter 49 - 29 August 1942

Chapter 50

Chapter 51 - 29 August 1942

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56 - 29 August 1942

Chapter 57

Part Eight - Sunwise

Chapter 58 - Lammas, 2006

Chapter 59 - January 1945

Author’s Note

Also by Jenni Mills

Copyright

About the Publisher

PART ONE Memory Crystals

‘History, archaeology, it’s all moonshine, really. We’re only guessing.’

Dr Martin Ekwall,

interviewed on BBC Wiltshire Sound

1942

‘Don’t be afraid,’ he says. The Insect King. ‘It’s only a mask.’

Eyes like a fly, elephant’s trunk that’s long, rubbery…

‘It’s only a mask,’ he says again.

‘I know it’s a mask,’ I says, braver than I feel. But there’s masks and masks. I’ve seen masks. I’ve seen what happens in the moonlight in the Manor gardens.

‘Frannie…’ It’s only a whisper, so I’m not sure if it came out of his mouth or out of my head. He’s at me now, pressing himself against me, and I’m feeling all the bits of him, long gropy fingers and the hard poky bits. There’s a glow in the sky, something burning near the railway yards, searchlights over Swindon, the banshee howl of the warning, and the anti-aircraft batteries have started up.

‘Take it off,’ he says.

‘The mask?’

‘Your flicking robe.’ At least, I think he says robe.

‘Coat.’

‘Whichever.’

‘A bit nippy for that.’ I’m trying to keep it calm, trying to be funny, pretend I’m in control, because this isn’t what I meant to happen. He gives me a push, quite hard, and I’m up against the stone. It’s cold against my back, like moonlight, and scratching at me like fingers through the thin material of my coat. There’s really nowhere to go now.

I would be afraid, but I won’t let myself. You can’t let them have everything. You can’t let them have your fear. You got to keep a bit of yourself. I’m going to put my bit where it’s safe, a long way away from here.

Beech trees, black against a silver sky. Somewhere else the real moonlight is pouring down. Bombers’ moon. A killing moon. Planes like fat blowflies trekking high above the Marlborough Downs. I take myself away, as far as I can, trying not to feel the burning down there, fingers, hands, other things, feels like there’s lots of them all at once, wanting a piece.

A voice whispering again, Frannie, Frannie. It’s terrible dark. There’s a smell of rubber, thick and choking. Hard to breathe. An awful slick, oily smell of rubber…

CHAPTER 1 Lammas, 2005

‘I don’t want to do it,’ I said. ‘It’s too dangerous.’

‘Don’t be ridiculous. The shots will be fantastic. You’ll love it. Unless you’d like us to use someone else on the series?’

The usual blackmail. If you’re experienced enough to do the job, you can say no. If you’re not quite twenty-five, and desperate to claw a foothold in television, you’ll do anything. I made one last pathetic attempt to get him to change his mind. ‘Seriously, Steve, I’ve never filmed like this before. I’m not properly trained. If this was the BBC, the hazard-assessment form would have it flagged up as a major risk.’

‘There’s a harness, Indy. You’ll be strapped in.’

‘My legs’ll be dangling.’

‘What’s happened to your balls?’

‘My balls, if I had any, would be dangling too.’

So, my legs are dangling. My non-existent testicles are dangling. My bum, perched on the edge of the open helicopter door, has gone entirely numb. Below me is–well, if I were a proper cameraman I’d be better at judging these things, but I’d say a good six or seven hundred feet of nothing. Below that is hard Wiltshire chalk, with a skimpy dressing of ripening barley. The helicopter’s shadow races across it, a tiny black insect dwarfed by the bigger shadows of the clouds.

Steve, crouched behind me, taps me on the shoulder. I turn my head towards him, very, very carefully, in case even this simple movement unbalances me and I go tumbling out to become another shadow on the chalk. He’s saying something, but the wind and the noise of the rotors snatch his voice away. He makes cupping motions with his hands by his ears.

He wants me to put the earphones on so I can hear him–he’s wearing a set with a microphone attached. Like I have, too, only mine are round my neck and not on my ears yet, and to put them on I’m going to have to let go of my death-grip on the door frame.

With both hands.

I send a signal from brain to fingers to unprise themselves. Nothing happens. Fingers know better than brain what’s sensible. They’re going to stay firmly locked onto something solid, thank you very much, until someone hauls me back safely into the interior of the helicopter and there’s no more of this dangling.

Steve taps me on the shoulder again. Maybe if I try just one hand at a time?

My left thumb, fractionally more adventurous than the rest of my hand, comes free. Right. That wasn’t so bad, was it? Clear proof it is possible to move and not fall out of the helicopter. In fact, now my thumb’s no longer involved, the fingers are really not doing that much to secure me, so I might manage to let go altogether that side…

Very good, Indy, but one hand doesn’t seem to be much help getting the headset onto my ears. All I’ve achieved is to get my hair into my eyes. Should have tied it back more securely. The headset has knocked the pins outs. I can’t see. Perfect moment for the helicopter to bank and drop down towards Pewsey Vale.

Oh, God, I’m going to fall out…

Steve’s hands gripping my ribs, hot breath in my ear. ‘Let GO!’ he yells, practically rupturing my eardrum. The shock loosens the other hand. ‘I’ve GOT you.’ His arm snakes round my waist. ‘Now put the flicking headset on.’

‘OK.’ Not that he can hear me until I do. I could spout a stream of hangover-distilled vitriol and the wind would whip it straight out of my mouth into nowhere. ‘I hate you, you spotty little toilet-mouth. I despise the fact you walked straight out of a media-studies degree and into a job as a producer just because your father was a foreign correspondent for ITN, while I’ve had to spend two years hoovering the coke off the edit-suite floor. I loathe that you get to tell me what to do, although I’m the more experienced of the two of us and you’re far and away the biggest twerp I’ve yet met in my admittedly not extensive media career. In fact, right now, because you made me do this horrible, scary thing, I’d be delighted if you leaned over too far and tipped yourself out of the bloody aircraft.’

Of course, I never would say it, don’t really mean it (not all of it, anyway), but imagining it has made me feel a whole lot better. I fumble the headset off my neck and onto my ears, using it as a kind of Alice band to keep my hair off my face.

‘Everything OK back there?’ Ed, the pilot, his voice tinny through the earphones.

‘Marvellous.’

‘Fine.’ Steve and I speak at the same time, both of us lying through our gritted teeth. He wants Ed to think we bear some resemblance to a professional TV crew; I want the man I slept with last night not to notice I’m a gibbering wreck.

Steve–the man I didn’t sleep with–retracts his arm. ‘Comfortable now?’

Comfortable doesn’t seem to be in it, but I feel more secure, and can admit it would be pretty difficult to fall out. Tough webbing straps are digging into my shoulders. They join in a deep V at the waist, meeting the belt that circles my middle and the strap that comes up from the groin. I’m very glad indeed, now I come to think of it, that I don’t have testicles, though to be truthful, life would be less painful without breasts. Wrapped in layers against the wind chill, even though it’s August–a duvet jacket I borrowed from Ed over two fleeces, and thermal long Johns under my jeans–I could still use more padding under the chafing straps.

‘Ready for the camera?’ asks Steve.

‘No.’

‘Look, you’d feel more balanced if you rested a foot on the strut. That’s what most cameramen do.’

‘Steve, I’m not most cameramen. I’m not six foot three. I’d have to be leaning right out of the helicopter for my leg to reach. You saw me try when we were still on the ground.’ I’m taller than scrawny little Steve, but that’s not enough–though it might have something to do with why we haven’t hit it off on this series. The main trouble is that Steve considers himself an expert. He’s been aerial filming more often than I have–which means he’s been out exactly once, and that must have been with a cameraman who had legs long enough to span the Severn Crossing.

‘Well, whatever.’ His real concern is how steady the shot will be. We both know we should have hired a footrest to screw to the helicopter’s landing skids, but it would have cost too much. ‘Now, can we please get a bloody move on? The budget only runs to two hours’ filming up here.’

Budget is, as usual, to blame for everything. The only job my limited experience (and lack of famous father–any father, for that matter) qualifies me for is assistant producer/researcher/camera/dogsbody at Cheapskate Productions, a.k.a. Mannix TV, who are making an entire series (working title: The Call of the Weird) on the televisual equivalent of about two and a half p. Today we are filming episode four, ‘Signs in the Fields’, which is about Wiltshire’s world-famous crop circles, after Stonehenge the county’s main tourist attraction. In fact, one year a farmer with crop circles in his field took more money from visitors than the ticket office at Stonehenge.

It took some doing to screw enough money for aerial filming out of the digital channel that commissioned the series, but crop circles can’t be fully appreciated from ground level. As it is, most of the programme will be made up of interviews in the back bar of the Barge Inn, on the Kennet and Avon canal and right in the heart of crop-circle country, with avid cerealogists, as crop-circle investigators are called. They will tell us (I know because as the series’ researcher I’ve already spent several hours listening to their theories) that only aliens could be responsible for such intricate and portentous patterns. It is simply not possible that such a primitive civilization as our own could have produced them. How could they have been made by humans? they ask, plaintively and rhetorically.

Well, I know the answer to that too. You need a thirty-foot surveyor’s tape, a smallish wooden plank, and a plastic lawn roller, obtainable from any good garden centre. I watched John do it, one moonlit May night in 1998, with a group of his friends who call themselves the Barley Collective. I was supposed to be the lookout but I was laughing so much that an alien mothership could have landed behind and I wouldn’t have noticed. The bizarre thing is that since people like John came out in the 1990s to admit they trample out the crop circles–gigantic art installations, the way John sees them–more people than ever have become convinced they can’t possibly be man-made. Apparently there’s a sociological term for it, John says, something to do with disconfirmation leading to strengthened belief, an idea that also lies at the heart of most religion. I gently put it to one of the cerealogists at the Barge that I’d seen it done, and he almost punched me.

Our time aloft this afternoon is limited, thank God, so limited I doubt we’ll achieve half of what Steve plans. He can’t afford to hire a proper cameraman–or a proper camera-mount, for that matter. Any minute now he’s going to thrust into my unwilling hands a DVC–digital video cam–secured only by a cat’s cradle of bungee cords. Financial constraints also dictated the choice of aircraft. We’re crammed into the back of a helicopter operated by 4XC, the CropCircleCruiseCompany, proprietor a wild Canadian called Luke, chief pilot his best friend Ed, with whom I made the enormous mistake of getting off with last night. Also in the helicopter are five paying passengers, three Americans and a Dutch couple, enjoying one of the aforementioned CropCircleCruises over Mystic Wiltshire. That way Steve hired flying time at a cheaper rate.

If I live, I’ll light a candle to the Goddess.

‘Crop circle coming up at two o’clock.’ Ed’s voice in the headphones. The helicopter lurches as three blond heads, a black ponytail and a bald spot all lean to the right to get a good look.

‘Jesus Christ, will you take the fucking camera off me, or we’ll miss it,’ snaps Steve, pushing the DVC in its sagging net towards me.

‘Relax,’ says Ed. ‘We’ll catch it on the way back.’ Almost as crazy as his friend Luke, who was drinking tequila shots last night in the pub, but fortunately more sober, and he seems to know what he’s doing. More than I can say for my esteemed director. For a moment I can feel sorry for Steve, trying to live up to his father, the famous name a curse tied to his inexperienced neck. I caught his expression while Ed and Luke were strapping me in, back on the ground. He looked like a little boy splashing in the bay, suddenly realizing that’s a big grey fin circling the lilo. Under other circumstances, this should have been fun, but he’s terrified we’ll fail to come back with any usable footage.

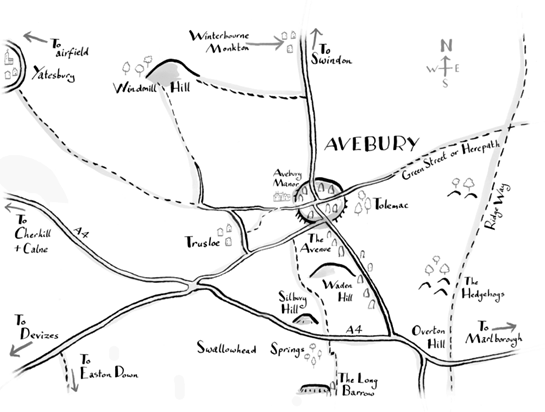

‘The best circles aren’t here, anyway, they’re at Alton Barnes,’ adds Ed, levelling the chopper. All I can see of him, if I twist in my harness, is the back of his neck, dark brown hair sticking out under his headset and over his collar. Hair into which I laced my fingers last night. I close my eyes with the embarrassment of it: what was I thinking? And if I’d known he was married…‘I’m going to head north first, to fly over Avebury for these guys.’

My stomach lurches, my gut contracting with the scary falling feeling of coming home.

Avebury: state of mind as much as a landscape. The place my family came from, where my grandmother was born and brought up–until the old serpent entered Eden, as Frannie used to say. A place I never lived in, apart from a few weeks one long-ago summer, but entering the high banks that enclose stone circle and village has always felt, in some strange way, like coming home.

Below us, the summer fields are gold, ochre, tawny, separated by knotty threads of green hedgerow. I’m getting used to the dangling now; it’s almost–but only almost–exhilarating. We fly over the Kennet and Avon canal, a brown ribbon winding away into the afternoon heat haze, little matchbox barges meandering along it, while the helicopter gains height to rise over the escarpment. I can see the long, double-ridged scar of the Wansdyke, an ancient Saxon boundary, bisecting the Downs, then the land folds and drops away and already there’s the ridiculous pudding that is Silbury Hill jutting out of the fog in the distance, so unmistakably not a natural feature that you can understand why CropCircleCruiseCompany makes money out of people convinced it was plonked there by aliens.

I bring the camera viewfinder up to my eye, and Steve’s hand grips my shoulder, helping to steady me while I get used to the weight.

‘Looks fabulous on the monitor,’ comes his tinny voice, breathless with relief. ‘We couldn’t be luckier with the weather, could we? Shame about the haze–makes the horizon a bit murky.’

‘Can you give me a white balance?’ I say, and he leans over me, inhumanly unworried by the yawning void, holding a piece of white paper in front of the lens. I make a quick adjustment, set the focus to infinity, and film the ground like a gold and green carpet being pulled away beneath us. Slowly tilt up to reveal Silbury and the whole damn distant shebang, humps, bumps, ridges and secrets you can only see from above, fading into a wash of pale umber that then shades into an overhead blue so intense it hums. Through the lens, height, motion and scariness are pared down to beautiful. OK, I’m a bit ropy still on the technicals (did I remember to set the toggle switch to daylight?) but this is what I’m good at, composing a picture: colour, angle, geometry.

Euphoria unexpectedly fills me, and I can even admit the sex last night was good; not to be repeated, but maybe forgivable. Guilt sneaks back with the memory of his fingers strapping me into the harness, and I enjoyed that too–why do I get myself into these scrapes? I should have made it clear before breakfast: I don’t do married men, full stop, after a nasty experience with a tutor at college–but there wasn’t time for conversation.

The helicopter loses height as we fly towards West Kennet Long Barrow–‘Just like a big vulva,’ says one of the passengers, the American woman, as I tilt down so it fills the frame–and then banks to the right, so my lovely shot ends abruptly in the clouds. I can hear the gnashing of Steve’s teeth because we’ve missed a close-up. We cross the A4–‘The old Roman road,’ calls Ed–and come over the green shoulder of the hill. A sigh comes out of me. There, at last, the first white tooth of the Avenue. I hadn’t even noticed I was holding my breath. The rotors are saying it: home, home, home. The image in the viewfinder is blurry, the wind pricking water into my eyes. England’s full of little exiles, and one of them happened at Avebury, for my grandmother, sixty-something years ago. One of them happened there for me, too, in 1989, so both of us were, in our own way, expelled from Eden.

Get in the van, Indy. Now

As far as blood relations go, Frannie is all I have. Grandfather, mystery man: not only did I never know him but neither did his daughter, born at the end of the Second World War after he was killed in action. Mother: well, best not to go there, but let’s just say she died, abroad, when I was in my early teens, having left me with my grandmother when I was eight. Father: itinerant Icelandic hippie my mother met in a backpacker’s hostel in Delhi, and never saw again. That was how I came to be called India. Could have been worse–Mum had been doing the world trip and I might have ended up with any name from Azerbaijan to Zanzibar.

We’re almost there, following the Avenue as it marches up the hillside. From above, the double row of stones looks tiny, but at ground level most are taller than a person. A single figure is walking between them, a dog racing ahead, then wheeling back to jump at the legs of its owner.

‘This must be the way they would process,’ comes a Dutch accent, female, in my headphones, separating the syllables. ‘Up from the Romans’ road, led by their priestess…’

Only a few thousand years out, not to mention one or two other errors, like there were no roads, unless you count the Ridgeway. And as for priestesses–well, I wouldn’t mind betting the boys were in charge back then, with the Neolithic equivalent of Steve leading the party. I swing the camera round–‘Great shot,’ breathes Steve, watching the image on the monitor wedged behind the seats–and pan along the course of the reconstructed Avenue, as we approach the village.

If Silbury Hill is an upturned pudding through the camera lens, Avebury is a bowl, an almost perfect circle of grassy banks and a deep ditch, surrounding a vast incomplete ring of stones. Five thousand years or so ago, those banks would have been gleaming white chalk, enclosing an outer circle of more than a hundred megaliths, with two separate inner circles, north and south, and more scattered sarsens within. Half the stones are missing now, like rotted teeth, some replaced with concrete stumps. Two roads meet near the middle, cutting the circle into quarters, and the village straggles along the east-west axis, a scatter of cottages half in and half out of the circle.

‘This is Avebury,’ calls Ed, moving up a notch into archaeological-tour-guide mode. He told me, last night, he’s doing a part-time MA in landscape archaeology with a view to getting into aerial survey. ‘Similar age to Stonehenge, but bigger–biggest stone circle in Europe.’

‘It’s like a giant crop circle, isn’t it?’ says one of the Americans. ‘D’ya think it coulda been, like, a signal to the aliens?’

Ed grunts in a way that could be roughly translated as For Chrissake, beam me up, Scotty. Down below, dots of colour between the stones mushroom into people as the camera zooms in. There’s a gathering over by Stone 78–the Bonking Stone, so-called because it’s conveniently flat–probably a handfasting. Someone is beating a small drum, arms moving rhythmically and flamboyantly, the sound inaudible above the noise of the rotors. I zoom in further, but it isn’t John.