скачать книгу бесплатно

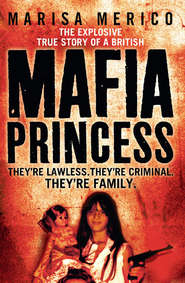

Mafia Princess

Marisa Merico

Marisa Merico, the daughter of one of Italy's most notorious Mafia Godfathers, was dazzled by her father, Emilio DiGiovine. To her he was all powerful, sophisticated and loving; to the rest of the world he was staggeringly ruthless. Marisa knew her father would do anything for her, but she hadn't expected just how much he would ask in return.Born to an English mother, Marisa turned her back on her quiet life in Blackpool to join her charming father, Emilio DiGiovine, who had spent years trying to tempt her back to Italy. Arriving in Milan, Marisa had no idea she was returning to the heart of one of the most notorious drugs, arms and money laundering empires in the world.At first her father shielded her from the family operations and Marisa was overwhelmed by the attention and gifts he lavished on her. But soon the temptation of a new recruit was too great and Marisa was drawn ever deeper into the family's sinister and brutal regime, witnessing things she was too scared to believe.The day she eloped with her father's chief henchman was the day her father decided she was ready to be initiated into the true nature of the family business. Suddenly Marisa saw there was no limit to what he would expect her to do for him. She knew it was wrong, she knew she had to get out, but she had no idea how she could break the sacred Coda Nostra – and survive.Marisa's extraordinarily story is the most powerful portrayal of a Mafia family to emerge in recent years. It's the perfect balance of shocking violence, dangerous betrayals and enduring love.

Mafia Princess

THEY’RE LAWLESS.THEY’RE CRIMINAL.

THEY’RE FAMILY.

Marisa Merico

with Douglas Thompson

FOR LARA AND FRANK

‘The family – that dear octopus from whose tentacles we never quite escape nor, in our inmost hearts, ever quite wish to.’

DODIE SMITH,

I CAPTURE THE CASTLE, 1948

‘But I don’t want to go among mad people,’ Alice remarked.

‘Oh, you can’t help that,’ said the Cat:

‘We’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.’

‘How do you know I’m mad?’ said Alice.

‘You must be,’ said the Cat. ‘Or you wouldn’t have come here.’

LEWIS CARROLL,

ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND, 1865

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u7249a9e0-c0a9-5378-8e98-156d7d39d303)

Title Page (#ucf645041-953e-5468-8841-83f6ac204de2)

Dedication (#u73a9af8e-978c-5302-8b9b-948c3eee32d2)

Epigraph (#u7b61200d-a903-51c1-8950-f34502f735f8)

FOREWORD (#u1975bfb0-1499-5f4f-b228-aa84dc66a4b3)

CHAPTER ONE GUCCI GUCCI COO (#u07110d1a-fa24-5064-a2f1-44e0e2d4efa7)

CHAPTER TWO WONDERLAND (#u899540c5-e014-59f7-917a-79f309f1ab44)

CHAPTER THREE MARLBORO WOMAN (#u3a1fa8c8-17b2-57cb-9e8f-d6a3d70c710d)

CHAPTER FOUR ROOM SERVICE (#u5bf46538-39da-5fc2-bb8d-52c6c7d51cce)

CHAPTER FIVE GUNS AND ROSES (#u012d240c-358d-5e71-b8a5-e2979ced3c08)

CHAPTER SIX COUNT MARCO AND THE DAPPER DON (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SEVEN THE GOOD LIFE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER EIGHT ROMEO (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER NINE STREET JUSTICE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TEN MAFIA MAKEOVER (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ELEVEN CAT AND MOUSE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWELVE BETTER OR WORSE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTEEN LA SIGNORA MARISA (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FOURTEEN RAINY DAYS IN BLACKPOOL (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FIFTEEN WHO’LL STOP THE RAIN? (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SIXTEEN LA DOLCE VITA (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN MEAN STREETS (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN BORN AGAIN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER NINETEEN FAMILY VALUES (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY DREAMLAND (#litres_trial_promo)

POSTSCRIPT GUN LAW (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

FOREWORD (#ulink_ab616686-9c61-5484-a6b3-c0dfe2afdf10)

‘Dream as if you’ll live for ever, live as if you’ll die today.’

JAMES DEAN, 1954

They shot dead my godfather with a 7.63 calibre pistol as he sat in his favourite barber’s chair waiting for a wet shave.

An explosive bullet from a high-precision rifle blew the top off my dad’s cousin’s head as he left his house, in the hurried moment between his front door and his armour-plated car.

An uncle of mine was gunned down by automatic fire as he was serving wine in his café-bar one lunchtime.

Soon after, the man who issued the orders for these murders was killed while in protective custody, as he took his Sunday morning exercise in the prison yard. A marksman aiming from a building outside the prison walls put a rifled, explosive bullet in his forehead.

With nearly seven hundred combatants and innocents already dead, the violence was escalating every day and my family was suffering. Which was why, at the age of nineteen, I agreed to drive South with a consignment of military weapons packed into the secret compartments of the family’s customised Citroën, the one that was usually used to traffic heroin.

We stacked machine pistols, handguns and rifles, clips of ammunition, bullet-proof vests and jackets on top of the heavier hardware: Kalashnikovs, those awesome AK-47S which can spray out 650 rounds a minute, and bazookas that toss armour-plated vehicles into the sky.

It was like packing your sweaters and skirts first in a holiday suitcase, having all the ironed stuff lying flat, your toilet bag and shoes stashed in the corners.

I was too young to understand the complexity of everything that was happening, and too dizzily in love with the boyfriend who came with me to feel scared – even when the carabinieri stopped for a chat alongside our car, where we had stashed away enough weaponry to start World War Three.

We didn’t have a fear in the world. It was just like going on a family summer holiday.

After our delivery, the war became even more intense. The rival families didn’t have the contacts to get military weapons like the Yugoslav bazookas we’d brought. Hit squads operated as four-men units: a driver, a shooter with a 12-gauge automatic Benelli, renowned in the lethal mechanics of urban warfare, two men with machine pistols. Russian RPGs, the antitank grenade launchers, were around. There were also arson teams to burn out the rivals who were taken down by rifle fire as they struggled to flee the flames.

Still it wasn’t all one way. Uncle Domenico – a lovely, lovely man, full of laughter and fun, my Nan’s brother, one of my favourite uncles – was shot dead as he strolled onto his bedroom balcony to smoke a cigar.

How many people have relatives who are shot and killed? I grew up with it.

These were insane times.

It was violence against violence and even then it was clear to me that the winner is the one who has the more homicidal equipment. And intentions.

I’ve learned such things for, even before I was born, violence was vital to my life.

It got me born.

CHAPTER ONE GUCCI GUCCI COO (#ulink_1f36e955-9ac6-5f5a-b264-80192e916e71)

Fidarsi è bene, non fidarsi è meglio.

[To trust is good, not to trust is better.]

ITALIAN SAYING

I was born on my Nan’s kitchen table. I emerged reluctantly, just in time for breakfast, in the middle room of her house in the Piazza Prealpi in Milan.

It was the same table on which my Nan had given birth to her twelve children, including her youngest, Angela, who’d arrived just four weeks earlier.

My mum didn’t have any contractions. She was taking her time to deliver me and Nan’s household wasn’t used to that.

‘Push! Push, push!’ Nan’s friend Francesca the midwife shouted at her.

Mum wasn’t pushing, not at all. She didn’t know what all the fuss was about. She was in a haze. She had no energy left. She’d been in labour for more than twelve hours.

‘Go on, push!’

Nan couldn’t understand the delay. When she’d given birth to Angela the month before, the production line had been as smooth as ever. This silly English girl on the kitchen table just didn’t have a clue how to have babies. Shouting wasn’t helping. The family had been up most of the night; they wandered around, yawning, trying to stay alert, but the coffee had stopped working hours before.

Now, at 8 a.m. on Thursday the 19th of February 1970, they’d had enough. Certainly my grandpa Rosario Di Giovine had. He wanted his breakfast.

‘Nothing’s happening, nothing at all,’ said Nan.

Grandpa rolled up his sleeve: ‘Right, come on! Come on, my girl…Vai! Vai!’

He gave Mum a real slap on the leg. Then another, harder, on the backside: ‘Come on – let’s have you.’

Mum pushed.

I arrived at 8.09 a.m.

Grandpa went off to eat, as if nothing had happened. My nan went to a cupboard at the side of the room. The midwife swaddled me in cotton cloths, and Nan returned with a purple cashmere Gucci blanket, a gift from an associate, and wrapped me up in it.

It was appropriate. I’d been born into the Mob. I was a Mafia Princess.

My mum didn’t have a lot of milk, so Nan breastfed me a few times. I loved my nan. I was always her favourite. Yet that Gucci blanket was no glass slipper. My early life was more like Cinderella’s before the prince came on the scene. And certainly no fairytale.

As I grew up, the family were ferociously pursuing their business, and that involved a great deal of guns and drugs and death. For my father’s family it had always been that way.

Nan was a pure bloodline Serraino, born in Reggio Calabria to one of the legendary ’Ndrangheta clans that make up the Calabrian Mafia. Pronounced en-drang-ay-ta, it translates as honour or loyalty, and loyalty to the family (or ’ndrina) is in the blood, flowing through their veins.

Nan can’t sign her name – she uses an X on documents – but she is one of the most remarkable Mafia figures of the past few decades, known widely as La Signora Maria, the Lady Maria. The authorities are ever so complimentary about her. I’ve seen Italian legal paperwork that ranks her the most dangerous woman in Italy.

I was named after her – Maria Elena Marisa (Di Giovine) – but people always called me Marisa; to avoid confusion, they said. Confusion? That was a good one. La Signora Maria is unique.

You don’t join the ’Ndrangheta; your membership is ordained. All Nan’s children knew the laws of such an indigenous and territorial Mafia family. They saw it as kids in Calabria, where my nan learned the gospel of violence first hand. People think that men run everything in the Mafia and the little woman isn’t even allowed to stir the pasta sauce. About half an hour’s sail across the Strait of Messina in Sicily, home of the Cosa Nostra, female roles were more like those you see in the movies, but in Calabria’s ’Ndrangheta, built for more than 150 years on the blood family, women have always been heavily involved in both the kitchen and the crime. There are even sisters in omertà – the Mafia code of silence. There are stories of initiation ceremonies for women not born into the family to be formally accepted. Blood relations and family ceremonies such as weddings, communions, christenings and funerals, are the core of the life. And death. There wasn’t ever a grey area with my nan. Nothing ambiguous about La Signora Maria.

She was the boss, the ultimate law.

And Pat Riley from Blackpool’s mother-in-law.

Mum was a stunner – blonde, shapely and fun to be around – but brought up in the suburbs of north-west England to be practical and sensible. Up to a point. She’s always been determined, her own person. The Blackpool Illuminations were never going to be the only bright lights in her life.

Patricia Carol Riley is a baby boomer, born on 17 January 1946, a little more than a year after her father, Jack Riley, returned from his wartime service in the ambulance corps. He and Grandma Dorothy had two more daughters, Gillian and Sharon. Granddad worked as a greengrocer, and Grandma had two jobs, one in a grocery store and another at the local Odeon. The long hours finally allowed them to buy themselves out of a council estate and into their own home for the sum of £3,000.

A treat for the girls was salmon paste sandwiches and tea on the beach next to Blackpool Promenade. It was a good life but quiet, ordinary. There were never going to be any surprises. It’s easy to understand that it got boring for a bright teenager like my mum.

She has her artistic side, she has an ‘eye’. She’s absolutely brilliant at art. She’s got an ‘A’ level in it and could have taught it but her dad wouldn’t let her go to art college. He thought it would be a waste of time – a degree and then she’d be off to get married and have kids. He and my grandma just wanted husbands, not complications, for their girls.

Mum was fed up. She liked her job as a window dresser for Littlewoods in Blackpool but she felt she was going down a predictable road, which she had to somehow turn off. As Monday to Friday rolled along she felt more and more trapped. She had a nice boyfriend: Alan, tall, good-looking and someone you could take home to fish fingers for tea. It wasn’t hot passion. When Alan started talking marriage, the alarm bells went off. There had to be something more, hadn’t there? Brenda, her best pal, had found that working as an au pair in America. Or so she said in her many gossipy blue airmail letters about the boys and the wild nights out.

‘America? Never!’ screamed Grandma Dorothy. ‘What’s wrong with life here? It’s good enough for the rest of us.’