Полная версия:

Red Runs the Helmand

PATRICK MERCER

Red Runs the Helmand

To my wife, Cait.

This is the third and final book in the Anthony Morgan trilogy: I will miss him and his friends. I would like to thank my wife, Cait, who has heard every word of this book more times than she cares to remember, my son, Rupert, and the staff of the 66th Regiment’s Museum in Salisbury. I canot forget Sue Gray and Edward Barker for their patience and forebearing and, of course, my agent, Natasha Fairweather of AP Watt and my faultless editor, Susan Watt.

Skegby, February 2011

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Epigraph

Author’s Note

Chapter One - Kandahar

Chapter Two - The Ghazi

Chapter Three - Khusk-i-Nakud

Chapter Four - The March

Chapter Five - Gereshk

Chapter Six - Eve of Battle

Chapter Seven - Maiwand, Morning

Chapter Eight - Maiwand, Afternoon

Chapter Nine - Retreat

Chapter Ten - The Siege

Chapter Eleven - The Sortie

Chapter Twelve - The Battle of Kandahar

Glossary

Historical Note

Also by PATRICK MERCER

Copyright

About the Publisher

Author’s Note

I’m amazed that anyone can soldier in Afghanistan at all. During several recent visits to that country I have found the heat almost unbearable and the ground unforgiving. Today’s soldiers have the advantage of wheeled and air transport (well, some of the time) but much of their fighting is done on foot burdened with personal loads of electronic equipment, body armour, helmets and the like that would have horrified their predecessors.

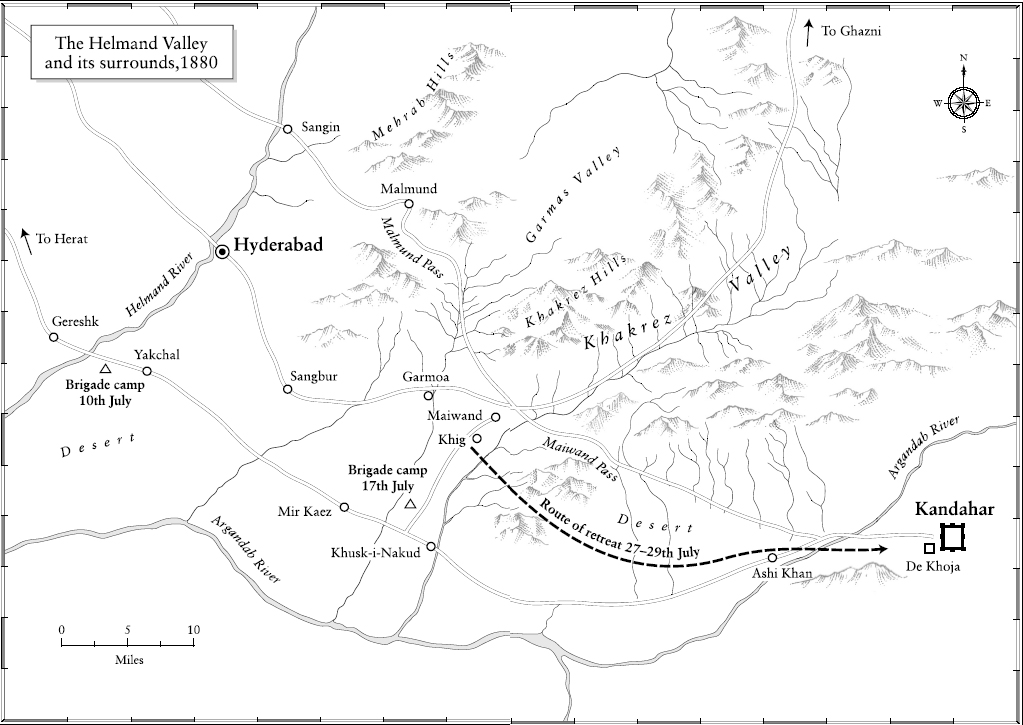

Most remarkably, though, the soldier of 1880, while carrying much less kit, survived on a fraction of the water that his great-great-grandson does. It’s noticeable how much logistic effort in the Helmand valley today is absorbed by the carrying forward of potable water – an effort that is directly equivalent to that needed for animal fodder in the 1880s. It has taken me some time to understand the priorities of an army in the field in the nineteenth century and the different privations they suffered.

Another challenge has been to grasp how the relationship between officers and men in the Indian armies actually worked. I’ve modelled this on the modern Gurkha troops alongside whom I served and the way that their British officers communicated with them. Nowadays, officers in Gurkha regiments have to pass exams in the language of their men. While a similar system was in its infancy at the time of Maiwand, British officers would have been surrounded by native dialects both on and off duty and this, I have no doubt, would have encouraged them to learn the language. But imagine how difficult communications would have been between, say, the 66th and Jacob’s Rifles; I’ve tried to capture some of this friction.

The language of my British characters, for obvious reasons, lacks the casual racism of the later nineteenth century, but I’ve tried to reflect the humour, candour and pragmatism of the time. In the same way, I believe that relationships then between officers and men in the British Regular Army were very similar to those of today. The film industry is, perhaps, most to blame for the impression that Victorian officers treated their men with a stiff, unbending formality but contemporary diaries and letters would utterly refute that. So, I’ve taken the heartbeat of the men with whom I served a hundred years later and sprinkled the way in which they spoke and joked with the military patois of imperial times; I hope I’ve got it right.

Anthony Morgan has now fought in the Crimea, the great Mutiny and the Second Afghan War, fearing much, slaughtering many and seeing more horrors than ten men. I’ve visited the home of the real Morgan in a delightful corner of County Cork and been treated with great courtesy by his descendants. It was there that Anthony actually retired to raise a family, pursue foxes and all other forms of wildlife and have a walk-on part in the Somerville and Ross books. I suspect that it is now time to let the fictional character enjoy some of the same.

Last, I’ve taken advice on almost everything in this book. If something is obscure, not covered in the glossary or just plain wrong, then it is entirely my own fault.

Patrick Mercer

Skegby

Nottinghamshire

Chapter One - Kandahar

‘No, Havildar, turn out the bloody guard, won’t you? I don’t want these two men standing there like goddamn sacks of straw. Just turn out the guard!’

I never could get my tongue round Hindi. It was all very well cussing native troops, but if they really couldn’t understand anything beyond the fact that you were infuriated with them, what was the point? In my experience, the angrier a sahib got them, the more inert and immobile they became. It was the middle of March 1860 and I’d only arrived in Kandahar after a long journey from India forty-eight hours before. And what a hole it was. The surrounding country was what I’d expected, all mountains, vertical passes and twisting, gritty roads; there was a rough beauty about it after the stifling lowlands of India. But the old city was not what I’d imagined at all. For a start, it was so much smaller than I’d thought. True, shacks, mud-built slums and thatched huts sprawled around outside the wall of the place, but the town itself wasn’t much bigger than Cork, yet it was packed twice as tight and smelt three times as bad.

Now, this little fracas at the gate came at the end of a long day when Heath, my brigade major, had proved to be even more useless than I’d thought. We’d been all round the units of my brigade, some of which were still dragging themselves into the town after the long march up from Quetta, although most of them had now arrived. I’d thought the Sappers and Miners’ horses slovenly – girths loose and fodder badly stowed. I’d found rust on more than one entrenching tool of the 19th Bombay and now, as I approached the Shikapur, or south, Gate of the city, Jacob’s Rifles – who had been the first to arrive and were meant to be finding the city guard – failed to recognise their own brigade commander. And what was that clown, Heath, doing about it? Was he chasing and biting the NCO in charge? No, I had to do it my-bloody-self.

Don’t misunderstand me, I was as keen as anyone else to get another campaign medal to stick on my chest, but from the very start of this punch-up, I’d had my doubts about being in Afghanistan. I’d never been convinced of how much the Russians really wanted to get a toehold on the Hindu Kush, but Disraeli had been persuaded by the political officers out here that there was more to it than the Tsar’s boys sending missions to Kabul and bending Amir Shere Ali’s mind against the British, so we had invaded in November ’78. All credit to Dizzy, Generals Roberts, Sam Browne and Stewart were backed to the hilt. Their three columns pushed hard into this miserable country, occupied Kabul after a bit of trouble, drove out Shere Ali and concluded peace with his son, Yakoob Khan, in May ’79. They’d bought the wily old lad off for the knock-down price of sixty thousand quid, after he’d promised to behave himself and accepted our Resident, Sir Louis Cavagnari. And there we’d all thought it had ended. If only that had been the case.

While others were grabbing all the glory (like that odious little sod Bob Roberts), I was still in Karachi, thinking that, as a forty-nine-year-old colonel, I’d reached the end of the career road, when news reached us of Cavagnari’s murder last September. Before that, there had been some pretty vicious fighting and we had all thought that his being allowed into the capital had marked the end of things – at least for a while. I reckoned we’d done quite a good job right across Afghanistan, but then, as usual, the windbag politicians had failed to open their history books and sent all the wrong signals to the Afghans. Instead of reinforcing success and giving the tribesmen the chance to sample the delights of imperial rule for a few months more, Whitehall listened too closely to the lily-livered press, the Treasury began to do its sums – and the tribesmen soon grasped that we had no plans to stay in their country beyond the next Budget Day. And who paid for that? Poor Cavagnari and his Corps of Guides bodyguard: butchered to a man in the Residency in Kabul. It was all a little too much like the last débâcle back in ’42 for my liking.

Then, of course, the papers really took hold. The blood of English boys was being shed for no reason, while innocent women and children were being caught by ill-aimed shells, the Army’s finest were being made to look like monkeys by a crowd of hillmen armed with swords and muskets. There were echoes of our last attempt to paint the map of Afghanistan a British red, of MacNaughton and Dr Brydon again. Then, to my amazement, three weeks ago, the Whigs won the general election: Gladstone found himself wringing his hands and ‘saving’ fallen women all the way into Downing Street. Now, with a card-carrying Liberal in charge, we all suspected we would quit Afghanistan faster than somewhat and certainly before the next tax rise, leaving the job half done and with every expectation of having to repeat the medicine once the amir or his masters in St Petersburg got uppity again.

‘What on earth’s taking them so long, Heath? We haven’t interrupted salaah, have we?’ I knew enough about Mussulman troops to understand that their ritual cleansing and prayers, when the military situation allowed, were vitally important. ‘Well, have we, Heath?’ But my brigade major didn’t seem to know – he just looked blankly back at me. ‘We need to make damn sure that when we’re in garrison all the native regiments pray at the same time. Otherwise there’ll be bloody chaos. See to it, if you please.’

I’d found out as much as I could about the general situation while I was on my way up here to take command of a thrown-together brigade. In it I had some British guns, Her Majesty’s 66th Foot and two battalions of Bombay infantry, while the 3rd Scinde Horse was in the cavalry brigade next door. By some strange twist of fate, I had one son in the 66th under my direct command while my other boy was in the Scindis, just a stone’s throw away.

Mark you, I was bloody delighted and a bit surprised to find myself promoted to brigadier general – but I was an old enough campaigner to know that a scratch command of any size would need plenty of grip by me and bags of knocking into shape on the maidan before I’d dream of allowing it to trade lead with the enemy – particularly lads like the Afghans: they’d given our boys a thorough pasting last year. And what I was seeing of the units that I was to have under my command left me less than impressed. Anyway, it was as clear as gin that if hard knocks needed to be dished out, my divisional commander, General James Primrose, would choose either his cavalry brigadier – Nuttall – or my old friend Harry Brooke, the other infantry brigade commander, to do it, wouldn’t he? After all, while they were both junior to me, they’d been up-country much longer.

Talking of being less than impressed, this little mob was stoking up all my worst fears. ‘Come on, man, turn out the guard!’ I might as well have been talking Gaelic. The havildar just stood there at the salute, all beard and turban, trembling slightly as I roasted him, while his two sentries remained either side of the gate, rifles and bayonets rigidly at the ‘present’. Of the whole guard, a sergeant and twelve – who should have been kicking up the dust quick as lightning at the approach of a brigadier general – there was no sign at all. And Heath just continued to sit on his horse beside me, gawping.

‘Well, tell him, Heath – I don’t keep a dog to bark myself, you know!’ I wondered, sometimes, at these fellows they sent out to officer the native regiments. I’d picked out Heath from one of the battalions under my command, the Bombay Grenadiers – where he’d been adjutant – because he’d had more experience than most and because he was said to be fluent. But of initiative and a sense of urgency, there was bugger-all.

‘Sir . . . yes, of course . . .’ and the man at last let out a stream of bat that finally had the havildar trotting away inside the gate to get the rest of his people. It was quite a thing to guard, though. The walls of Kandahar were packed, dried mud, thirty foot high at the north end, faced with undressed stone to at least half that height and topped with a fire step and loop holes for sentries. The Shikapur Gate was a little lower than the surrounding walls. It was made up of a solid stone arch set with two massive wooden gates, through which traipsed a never-ending procession of camels, oxen and carts, carrying all the wonders of the Orient. Now, the dozen men came tumbling out of the hut inside the walls that passed for a guardroom, squeezing past mokes and hay-laden mules while pulling at belts, straps and pouches, their light grass-country shoes stamping together as the havildar and his naik got them into one straight line looking something like soldiers.

If I’d been in the boots of the subaltern who’d just turned up, though, I’d have steered well clear. I’d dismounted and was about to inspect the jawans when up skittered a pink-faced kid, who looked so young that I doubted the ink was yet dry on his commission. He halted in the grit and threw me a real drill sergeant’s salute – as if that might deflect my irritation.

‘Sir, orderly officer, Thirtieth Bombay Native Infantry, Jacob’s Rifles, sir!’ The boy was trembling almost as much as the NCO had done – God, I remembered how bloody terrifying brigadier generals were when I was a subaltern.

‘I can see you’re the orderly officer. What’s your name, boy?’ I knew how easy it was to petrify young officers; I knew how fierce I must have seemed to this griff and he was an easy target for the day’s frustrations – I wasn’t proud of myself.

‘Sir, Ensign Moore, sir.’ The boy could hardly speak.

‘No, lad, in proper regiments you give a senior officer your first name too – you’re not a transport wallah with dirty fingernails . . .’ I knew how stupidly pompous I was being ‘. . . so spit it out.’

‘Sir, Arthur Moore. Just joined from England, sir.’

But there was something about the youngster’s sheer desire to please that pricked my bubble of frustration. If I’d been him, I would have come nowhere near an angry brigadier general – I’d have found pressing duties elsewhere and let the havildar take the full bite of the great man’s anger. But no: young Arthur Moore straight out from England had known where his duty lay and come on like a good ’un.

‘You’re rare-plucked, ain’t you, Arthur Moore?’ I found myself smiling at his damp face, all the tension draining from my shoulders, all the pent-up irritation of a day with that scrub Heath gone. ‘Let’s have a look at these men’s weapons, shall we?’

Well, the sentries may have been a bit dozy and not warned the NCOs of my approach, and the havildar’s English may have been as bad as my Hindi, but Jacob’s rifles were bloody spotless. Pouches were full, water-bottles topped up and the whole lot of them in remarkably good order. It quite set me up.

‘Right, young Moore, a slow start but a good finish. Well done.’ I tried to continue sounding gruff and impossible to please, but after all the other nonsense of the day, this sub altern and his boys had won me over.

‘Shabash, Havildar sahib . . .’ It was the best I could manage as I settled myself back into the saddle.

‘Shabash, General sahib.’ The havildar’s creased, leathery face split into a grin as the guard crashed to attention and Moore shivered a salute. Perhaps, after all, there was some good in the benighted brigade I’d been given.

No sooner had I had my sport with the lads on the gate and arrived at the mess rooms that had been arranged for me than I was summoned to the Citadel to report to my divisional commander in his headquarters, which the great man had set up in the old building. Now, Kandahar had been occupied by General Donald Stewart’s Lahore Division during the initial invasion, so when our division had been ordered to tramp up from India to replace Stewart’s lot, I’d expected to find the town in good order and all ready to be defended – after all, the Lahore Division had arrived in the place more than a year ago. However, apart from skittering about the Helmand valley, they appeared to have done absolutely nothing to prepare the place for trouble. They’d just loafed about before being ordered to clear the route back to Kabul, leaving us of Primrose’s division to put the place in some sort of order.

At the north end of the town, just within the walls, there was a great, louring stone-built keep of strange Oriental design. There may have been some fancy local name for it, but we knew it simply as the Citadel. I’d never seen anything quite like it: its curtain walls were a series of semi-circular towers, all linked to one another, with a higher keep that dominated them in turn. I don’t know when it was built, probably more than a century before, but it was solid enough and could have been made pretty formidable. But Stewart’s people hadn’t thought to mount a single gun on it, while almost two miles of old defensive walls, which stretched in an uneven rectangle south of the fort, had been neither improved nor loop-holed. Meanwhile, the garrison’s lines were sited nice and regimentally, but with no more thought for trouble than if they’d been in bloody Colchester! Had they learnt nothing after Cavagnari’s murder and the bloodbath in Kabul last September?

‘Here, General, look at those ugly customers.’ Heath, my brigade major, had failed to read my mood, as usual, and was being his normal irritating self. ‘Ghazis, you can bet on it.’

Heath, Lynch – the trumpeter who had been attached to me by the Horse Gunners – and I were hacking along from the cantonment to meet our lord and master General Primrose up in the Citadel. There, I was expected to report my brigade present and correct to Himself. I would also be briefed on the situation.

‘Ghazis? Why d’you think that, Heath?’ I looked across at a handful of young braves who were filing along past a scatter of native stalls on the edge of the bazaar. Lean, tall, well set-up men, their hook noses and tanned skin told me nothing exceptional; they carried swords, shields and jezails slung across their backs, like half of the rest of the men in this town, and looked me straight in the eye, rather than slinking away, like most of the other tribesmen do at the sight of Feringhee officers. ‘They look more like normal Pathans to me. I’ve a notion that Ghazis don’t carry firearms.’ Those who knew told me that the Ghazis, Islamic zealots from the most extreme sects who had sworn to die while trying to kill any infidel who trod upon their land, did their lethal duty with cold steel only, eschewing muskets and rifles as tools of the devil.

‘Possibly, General, but you never quite know how they’ll disguise themselves. Look at their arrogant expressions,’ Heath continued. When I’d picked him, I’d assumed that, with all his service in India and his fluent bat, a degree of common sense and knowledge of the workings of the native mind would come with it. Both appeared to have eluded him – he was even more ignorant of local matters than I was.

‘No, sir, they ain’t Ghazis.’ Trumpeter Lynch had been part of my personal staff for less than twenty-four hours, but he’d already seen through my brigade major. ‘If they was Ghazis they’d have buggered off at the sight of us, sir. My mate who was in Kabul last year reckons you’ll only see one of them bastards when he’s a-coming for you, knife aimed at yer gizzard. No, sir, them’s just ordinary Paythans, like the general said.’

Heath might have been wrong on that score, but he was right about their arrogance. They all continued to stare at us. The oldest of the group, a heavily bearded man without, apparently, a tooth in his head, spat on my mounted shadow as it passed them by, expressing his contempt most eloquently.

‘A trifle slow off the mark, Morgan?’ Major General James Maurice Primrose and I had never liked each other. ‘I asked for you to be here at half past the hour. It’s five and twenty to by my watch.’

The sergeant of the Citadel guard had been a smart but slow-witted man from the second battalion of the 7th Fusiliers who’d been incapable of directing my staff and me to the divisional commander’s offices; none of us had been there before and Heath hadn’t thought to check. So, to my fury, I was late and last, giving Primrose just the sort of opening I’d hoped to avoid. We’d first met in Karachi a couple of years ago and, both of us being Queen’s officers, we should have got along. But we didn’t. He was one of those supercilious types who’d never got over his early service in the stuck-up 43rd Light Infantry and, I was told, envied both my gong from the Crimea and my Mutiny record.

‘Still, no matter, we’ve time in hand. Now, while I need to know about your command, I’ve taken your arrival as an opportunity to bring all my brigade commanders up to date on developments. Forgive me if you know people already, but let me go round the room.’ Primrose was small, standing no more than five foot six, just sixty-one and with a full head of snowy hair. There had been rumours about his health, but he seemed to have survived. Now he pointed round the stuffy, low-ceilinged room with its two, narrow, Oriental-style windows. ‘Nuttall commands my cavalry brigade.’

I’d never met Tom Nuttall before but I’d heard his name bruited about during the Mutiny. A little older than I was, he was an infantryman by trade but now found himself in charge of the three regiments of cavalry – including my son Sam’s regiment, the 3rd Scinde Horse. He was as straight as a lance, clear-eyed, and had a friendly smile.

‘I know that you know Brooke.’ I thought there was a distinctly cool tone in Primrose’s voice as he waved a hand at Harry. Yes, I knew and liked him for he was a straight-line infantryman like me, a few years younger, but he’d seen more than his share of trouble in the Crimea and China before rising to be adjutant general of the Bombay Army.

‘And McGucken tells me you two stretch back a long way.’ Again, I thought I caught irritation in the general’s voice as Major Alan McGucken reached out a sinewy hand towards me, his honest Scotch face cracked in the warmest of smiles.

‘Yes, General, we’ve come across one another a couple of times in the past. It’s good to see you again, Jock.’ By God, it was too. Six foot and fifty-four years of Glasgow granite grinned at me, one of the most remarkable men I knew. He was wind-burnt, his whiskers now showing grey, and wore a run of ribbons that started with the Distinguished Conduct Medal on the breast of his plain blue frock coat. I’d first met him when he was a colour sergeant and I was an ensign in the 95th Foot. We’d soldiered through the Crimea and the Mutiny, never more than a few feet apart (we were even wounded within yards of each other), until his true worth had been recognised. After the fall of Gwalior in ’58, he’d been commissioned in the field and, with his natural flair for languages and his easy way with the natives, he had soon gravitated back to India. I’d watched his steady rise through merit with delight and pleasure but had been genuinely surprised to hear that he’d been seconded to the Political Department, some eighteen months ago, and then appointed to advise the divisional commander here in Kandahar.