Полная версия:

Black Earth: A journey through Russia after the fall

BLACK EARTH

RUSSIA AFTER THE FALL

ANDREW MEIER

PRAISE

‘There is depth to Andrew Meier’s portrait of Russia, but breadth as well. The treasures lie in his love for the country and the nuances that emerge from his encounters with Russian soldiers, politicians, pensioners and public servants’

Books of the Year, Economist

‘Written with curiosity, wit and sensitivity [Andrew Meier’s Black Earth is] a superb and erudite journey into the Russia he loves and knows better than virtually any other writer of his generation: it is the best work of Russian reportage since the fall of Communism’

SIMON SEBAG MONTEFIORE

‘The best piece of journalism written about Russia in English, and likely to remain so for a long time … The detail, knowledge and, above all, understanding which reside in this book remind us of how good journalism can be: how the first draft of history can be its freshest, its most poignant and its most alive … a record of extraordinary quality’

Glasgow Herald

‘Andrew Meier is not only a highly skilled journalist but also a remarkable listener … Black Earth is compelling and richly readable’

Mail on Sunday

‘A remarkable book. From the powerful first paragraph to the hopeful last it grips and grabs and stays with you. Highly recommended’

Ireland on Sunday

‘Impressive, building up to a many-layered portrait of post-Communist Russia … Meier has a genuine affection for the country and its people, which helps him to see beyond the one-dimensional image one gets from foreign newspaper reports’

Independent on Sunday

‘Moving … fascinating … Beautifully written and serves as a forceful reminder of quite how hard it will be to make real changes in Russia beyond the Moscow ring road’

Literary Review

‘[Meier] talks to gangsters, apparatchiks, intellectuals, oligarchs. He gives us not merely the buzz and glitter of Moscow and St Petersburg, but the squalid house-to-house fighting in Chechnya and – a rare experience – distant decaying Sakhalin beyond the Strait of Tartary’

Books of the Year, Times Literary Supplement

DEDICATION

for Mia,

and for my parents

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Praise

Dedication

Prologue

I. Moscow: Zero Gravity

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

II. South: To the Zone

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

III. North: To the Sixty-Ninth Parallel

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

IV. East: To the Breaking Point

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

V. West: The Skazka

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

VI. Moscow: “Everything Is Normal”

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

P.S. Ideas, Interviews & Features …

About the Author

Interview with Andrew Meier

Life at a Glance

About the Book

A Critical Eye

Afterword After Beslan

Russian Write Off

Read On

If You Loved This, You’ll Like …

To Find Out More, Andrew Meier Recommends …

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Author’s Note

Notes

Copyright

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

HE HAD BEEN THEIR FIRST CHILD, the elder of two sons. After his death they had turned the darkest corner of the spartan living room into a shrine. A hazy black-and-white portrait, blown up beyond scale from an army ID, loomed above the reedy church candles and a thin bouquet of plastic flowers. They had draped a black ribbon over the photograph.

“When I served,” his father said, “I served the Motherland. ‘To serve with honor and dignity.’ That’s what they told us to do and that’s what I did. For twenty-eight years.”

Andrei Sazykin died in the summer of 1996. He was killed on the north-eastern edge of Grozny, before dawn broke on August 6, the parched day the rebels reclaimed their capital. The Chechens had swarmed back by the thousands. Seven other boys in his unit also fell that morning. Three weeks earlier Andrei had turned twenty.

For the Russian forces, the Sixth of August, as it became known, would live on. It would haunt them as a humiliation, the worst day of the war. For Andrei’s parents, Viktor and Valentina, it made no sense. They would sit in the dim light of their two-room apartment in Moscow and wonder how the Chechens had so easily retaken Grozny that day. Until the letters started to arrive. One after another, Andrei’s comrades began to write to his parents.

“And suddenly,” his father said, “everything came into this terrible perfect clarity.”

The letters were blunt.

“‘Your son served well,’” recited Viktor. He had read the words a thousand times, but he traced the lines with his forefinger. In his voice there were tears. “‘But he did not die in battle. He was sold down the river. We all were.’”

Valentina said the boys came to visit. They brought a video from their last days in Chechnya. It showed Russian officers, their shirts off in the severe heat of Grozny, playing backgammon with two Chechen fighters. They were smoking and drinking, all of them laughing.

“That was the afternoon on the day before Andrei died,” Viktor said. “The boys later pieced it together. There was no battle that morning. There was a deal. The Chechens paid their way through the checkpoints. The boys were slaughtered. And when the others went looking for the commanders, they were gone”

Months after their son’s death Viktor and Valentina brought a case, one of the first of its kind in Russia, against the Ministry of Defense. They sued to restore their boy’s honor and not, as the papers claimed, to get rich on compensation. They called his death a murder and vowed to seek punishment for those who killed him.

Several Augusts later, nearly five years to the day after their son died, I went to see them again. We had spoken in the intervening years. But I had never brought them the kind of news they craved, for I had failed to convince my editors that their son’s case was a story. I had, however, followed Viktor and Valentina as they waged their long campaign. They had started in their neighborhood court and fought all the way to Russia’s Supreme Court. They even won a hearing in the Constitutional Court. But at every station they lost.

Along the way Valentina lost her job. For two decades she had taught biology in the local school. Viktor meanwhile had been forced to get a job. He now worked twenty-four-hour shifts, four times a week, at an Interior Ministry hotel, a hostelry for visiting officers in Moscow. Their savings depleted, they had also lost their hope. All they had, said Valentina, was nashe gore (“our sorrow”).

“Tell me,” Viktor said, fixing his eyes on mine. “Because I can’t understand it. But you must know. Can a country survive without a conscience?”

In the days that followed our last conversation, I left Moscow after a stay of five winters and six summers. I had, truth be told, lived in the country for most of the last decade. I had seen out the last years of the Soviet experiment and witnessed the heady birth of the “new Russia.” I had seen the romantic rise of Boris Yeltsin-and the wreckage his era wrought: the inglorious battle for the spoils of the ancient regime (an industrial fire sale of historic proportion), the military onslaught in Chechnya (the worst carnage in Russia since Stalingrad), and the rapid decline in nearly every index, social and economic, that the state took the trouble to record.

I had traveled far beyond the capital, to the distant corners of the old empire. I had lived for years in the remains of the Soviet state amid the millions of spectral dead souls who walked its ruins, as well as the rising new class of rent seekers, instant industrialists, and would-be entrepreneurs, who raced to accumulate and acquire, lest their new world vanish as quickly as the old. I had interviewed Politburo veterans and Gulag survivors, befriended oligarchs and philosophers. But I had no answer for Andrei’s parents. I could only tell them that I hoped to write a book – not only to record my travels across Russia’s length and breadth but, above all, to try to make sense of their plaintive question.

I. MOSCOW ZERO GRAVITY

Vykhod est’! (“There Is a Way Out!”)

–Moscow metro slogan, 2001

ONE

IN THE OLD DAYS, before the breakneck final decade of the last century, before the end of empire and the epochal shift that followed in its wake, in the days when dissenters were dissidents and poets were prophets, when “abroad” meant Bulgaria, Budapest, or Cuba at best, when leather shoes and silk ties were not bought but “gotten,” when colleagues were “Comrades” and strangers “Citizens,” when HIV and heroin were exotic plagues born of bourgeois excess, when artists and soldiers pointed to ceilings and dropped their voices, when churches held archives and orphans, when lovers met in parks because apartments housed generations, when everyone professed to believe in the Party, the Collective, and Vodka but in truth trusted only Fate, God, and Vodka, I first came to Moscow.

By the time I left, I had lived there longer than in any other city. But Moscow, like the country that surrounds it, eludes one. It defies measurement and loathes explanation, as if inherently ill disposed to definition. Longevity in Russia does not always yield understanding. Neither does intimacy guarantee knowledge. Nor does the first sensation of walking the city’s poplar-lined boulevards and great avenues of granite, that first sense of awe and astonishment at the fairy-tale world turned nightmare, ever seem to diminish.

First impressions in Moscow fortunately do not lie. The city is built on an inhuman scale. Everything is by design inconvenient for Homo sapiens. The streets are so vast crossing them requires a leap of faith. The cars do not stop for pedestrians; more often they accelerate. The streets are so broad one can traverse only beneath them, through dimly lit passageways that shelter the refugees of the new order: makeshift vendors who hawk everything from Swedish porn to Chinese bras; scruffy preteens cadging cigarettes and sniffing glue; hordes of babushkas who have fallen through the torn social safety net and are left to sell cigarettes and vodka in the cold; the displaced stranded by the host of unlovely little wars that raged along the edges of the old empire. And everywhere underground the stench of urine lingers with the acrid aroma of stewed cabbage and cheap tobacco.

Aboveground the city seems to exist – as it did at its birth – to trade. Kiosks on nearly every corner, bazaars in every neighborhood. Even the outlying districts, more a part of the woods than the city, are overrun with feverish commerce. In the post-Soviet years, open-air wholesale markets, sprawling encampments of plastic tenting and cargo containers, lured tens of thousands each weekend. Here were the fruits of globalization, tinged inevitably with a Russian style: electronic and computer goods from the East and from the West, pirated software on CDs burned locally and on video, Hollywood blockbusters still unreleased in the States. The off-the-books trade united unlikely partners. A drug market sprouted one block from the Lubyanka, the once and present headquarters of the secret police, on a street where pensioners sold their prescriptions to hungry young addicts.

Slowly, too, the signs of the new opulence – the transfer of the state’s vast wealth into the hands of a chosen few – came to dominate Moscow’s implacable center. Vacant nineteenth-century mansions, the crumbling former residences of the prerevolutionary merchant class, became the ornate offices of new millionaires and billionaires, the men who soon took to calling themselves oligarchs. Even during the harshest years of the Communist era, Moscow had always been on the make. But in the mid-1990s, with the rise of powerful moguls like Boris Berezovsky, Vladimir Gusinsky, and Vladimir Potanin, among a half dozen others, the Great Grab began. In the bedlam of the Yeltsin years, the profit margin grew into a gaudy obsession. “The primitive accumulation of capital” was what the oligarchs, remembering their Marx, called their thirst for the riches of the ancien régime.

This of course was “the New Moscow.” When I first stepped foot in the city in 1983, Moscow was grim and gray, a place of vast public spaces dominated by an eerie silence. It was the height of the age of Yuri Andropov, one of the last of the dour old men to rule the USSR. The Soviet war in Afghanistan was at its tragic height. I was then a nineteen-year-old undergraduate on a cheap one-week Sputnik tour. I had flown in from East Berlin with two dozen Bavarian high school students and, inexplicably, an older businessman from Buenos Aires who mesmerized the Kremlin guards with a new invention, a video camera.

My eyes glazed at the strange fairy-tale world. In the kaleidoscope of sounds and impressions, Moscow, it seemed, hosted another race on another planet. One encounter, above all the rest, remains indelible, fixed in the present. I sit on a low brick wall on a corner of Red Square. As I watch the crowds moving across the square, a young boy approaches. His name is Ivan. But I do not understand him when he tells me his age. He holds up ten fingers and folds down one pinkie. Nine, I understand. We cannot speak with each other. We only manage to establish two things. “Lenin tut,” Ivan says, pointing to the squat red granite mausoleum that sits across the cobbled square. “I Mama tam.” (“Lenin is here. And my mama’s over there.”) He waves a hand to swat the air, pointing to an office that lies far beyond this great busied corner of Moscow. That afternoon I made a vow to myself: I would return to Russia only once I had learned the language.

Five years later I did. In 1988 I came back as a graduate student from Oxford to study for a term. I never expected, of course, that I would stay on in Moscow to witness the USSR during its final gasps. After Oxford, there was only one place I wanted to be, where I had to be. I told family and friends that I was making my way as a free-lance journalist. In truth I was searching for any excuse to stay in Moscow. I was in love.

In those final, frenzied years of the Soviet Empire, Russian friends often wondered why I chose to live among them. My friend Andrei, then in the advanced stages of a doctoral dissertation on the liberalizing impulses of Josip Tito’s economics, was no Soviet patriot. The son of a middling Soviet bureaucrat, Andrei had a fondness for tie-dyed jeans and peroxided hair. He had offered to let me stay with him and his young wife, Lera, and their five-year-old daughter, Dasha, in their kommunalka, a communal flat they shared with a young woman and an old lady in one of the city’s most beautiful and crumbling prerevolutionary neighborhoods. Andrei and Lera were lucky; theirs was hardly the typical communal flat. The young woman worked in a sausage plant. She rose early, came home late, and at week’s end without fail brought home frozen pork. The old lady was even more accommodating; she rarely appeared.

They lived a quarter mile from the Kremlin, but Andrei and Lera could not have been further removed from officialdom. Each night brought friends: rock musicians and military officers, actors and poets, tall, stunning women from Siberia, short, stunning men from Dagestan. Their cramped kitchen was always crowded with the voices of the emergent generation debating the issue of the hour, be it the chances for Gorbachev and glasnost, the Soviet pullout from Afghanistan, or the legalization of hashish in Copenhagen.

The gatherings grew so big that one Sunday morning Andrei axed his way through a wall, expanding the tiny kitchen into an unused closet. As the nightly assemblies ran their course, accompanied by the ceaseless flow of bottle after bottle, the attention turned to me.

“Just why are you here?” someone would ask.

“He’s looking for a Russian bride,” someone would joke.

“He’s a spy,” another would jibe.

Whenever doubt or suspicion arose, Andrei saved me. “He just enjoys watching dead empires in decay,” he’d answer.

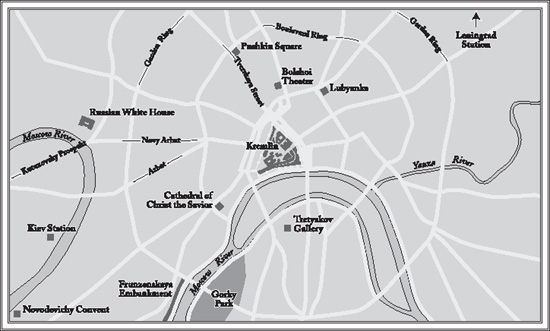

DAYS BEFORE THE COUP attempt against Gorbachev in August 1991, I left Soviet Russia. But in 1996, after a five-year remove, I returned again. This time I came with my wife, Mia, a native New Yorker and a photojournalist. We moved into a single room with a remarkable view. It was on the top floor of a fabled building that rose above the Frunzenskaya Embankment along the Moscow River. One side of the building overlooked the river and Gorky Park, the other – ours – had a view of the Novodevichy (New Maiden) Convent. On long walks along the river we would wonder at the glimmering cupolas of the Kremlin churches and savor the sweet air that wafted from the Red October chocolate factory across the way.

The building, erected in the lean postwar years, was a landmark. Stalin had built it not only as an elegant residence for his lieges but as evidence that their world would survive. This explained the decor. Our room stretched, at most, twenty-five by ten feet but boasted a corniced ceiling and an outsize crystal chandelier. Each month Nikita Khrushchev, the moon-faced grandson of the Soviet leader, came for the rent. The place belonged to his other grandfather, his mother’s father. The quarters were tight, even by Russian standards, but more than we needed. I had a fellowship to report from the war zones of the former USSR, and our plan was to spend as much time as possible on the road, traveling across Central Asia and the Caucasus. We took the place for a few months, and we stayed there three and a half years.

That fall I joined Time, trading the freedom of free-lancing for my first monthly paycheck as a journalist. Nonetheless, we stayed on in our room. As a “local hire” I got a bare-bones contract. We still slept on the couch, did the laundry in the bathtub, and delighted in the discovery of Belgian flash-frozen chicken in the corner market. We installed a steel door and scoured the local street vendors for fresh vegetables. Mia made friends with an Azeri woman, a refugee from the war between the Armenians and Azeris in Nagorno-Karabagh, who set aside her fattest potatoes and tomatoes for us. When rare visitors from home arrived, we made sure to prepare them for the elevator. We lived on the fourteenth floor. The elevator was wooden, a rickety antique that screeched as it slowly ascended. Invariably, it was pitch black inside. Now and then a neighbor screwed in a light. But it did not stay for long. Ten bulbs, I soon learned, equaled a bottle of vodka. In all our years in Moscow we never lived in the ghettos reserved for foreign diplomats and journalists, and for this we would be grateful.

The house was filled with stories and sources. Lazar Kaganovich, one of Stalin’s longest-serving henchmen, had lived on the next stairway over. (His daughter still did.) Next door to us lived Sasha, an aging underground painter who had been one of the first to stage avant-garde actions in the city streets. He still spoke proudly of the day under Brezhnev when he walked into a barren meat store and placed paintings of sausages and hams in its empty display counters. His wife, a restorer of fine art, worked for the Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow’s grandest museum. Throughout the first winter that we shared a wall, she worked on canvases the soldiers had brought home from the Grozny Art Museum. Sasha was usually mild-mannered – except when he drank, which was often. One day he decided Mia would make a new drinking partner. He hovered outside our door, pounding it with a bottle of vodka, until as she refused, he sank to his knees, crying.

On the floor below lived Nina Aleksandrovna, a frail lady in her seventies who took a warm liking to us. Poor Nina was tortured by her son, Sergei, who seemed lost in a détente time warp. He wore faded denim shirts, unbuttoned low, and faded jeans. At least twice a week he would appear at our door to plead with me to translate some Beatles song. Sergei drank too much and worked too little.

Pyotr lived next door to Nina. A lanky hacker with a blond ponytail, he later showed me, as NATO jets bombed Belgrade, how he helped lead the attack on the North Atlantic Alliance’s mainframe. When we first met, Pyotr was a nineteen-year-old who resisted wearing shirts, no matter the weather. He and I spent long nights on the landing between our floors. We would look out at Novodevichy, the most fabled convent in Moscow. He rolled cigarettes – no filters, Dutch tobacco – and talked of his course work. He was majoring in one of Moscow State’s new fields, the Department of the Defense of Information. Pyotr was already one of Moscow’s more established hackers; he anchored a TV show on pirated computer games and had bought a small dacha. One night he told me who was paying for his education, the FSB. He was on a full ride from the secret policemen who had taken over for the old KGB.

TWO

IT WAS EARLY ON A CRISP Saturday morning in the short Russian fall, and something was not right. The mayor had sensed it. He was sure of it, in fact. Tiles crack. They break. They splinter. Linoleum, he calculated, would last. The mayor sat in the center of the head table in a prefabricated construction office built of American aluminum siding and Finnish plywood in the heart of Moscow. He stirred slowly in his chair, staring straight ahead, as if seeing something far beyond the realm of all the eyes gathered here and fixed upon his tonsured square head.