скачать книгу бесплатно

Chapter 75 (#ud6b0fe00-dbce-53ab-add5-f9f1c29e0794)

Chapter 76 (#u02ee4eb3-3796-5e08-b85c-d002bf4590d8)

Chapter 77 (#u9ad2186e-3f06-5f21-8120-ec3607df9963)

Chapter 78 (#u71289200-89a2-5c62-ac0a-45ab53a53316)

Chapter 79 (#u99bc0d93-4bca-5636-a387-d98327637a71)

Chapter 80 (#u3c77ba97-b8b9-540a-947d-eba038e8f49c)

Chapter 81 (#u6fceb9ad-435b-564f-92de-8dc3295ec6e6)

Chapter 82 (#u1c30801c-ab83-586c-9fb9-611b99ac3c82)

Chapter 83 (#ue3b4f53a-4503-589d-9435-04a6156ef118)

Chapter 84 (#ud43844f9-55a0-5b0f-a207-96e4ed059d39)

Chapter 85 (#uca50bd4c-3cf6-567b-bdb7-05c181881132)

Chapter 86 (#u5ebd67fc-62cb-5905-8a41-eb0c6306a6fb)

Chapter 87 (#ube53b297-9d5b-5386-95f0-a4f448a995a0)

Chapter 88 (#ua943cf1f-02a4-58c2-9c22-4c34dbca4f94)

Chapter 89 (#u80f7fbab-b5d7-5b32-b320-6d2a29e770d2)

Chapter 90 (#u7ae3ee79-e0a0-5978-a2b1-84e0118729e2)

Chapter 91 (#u55c27e03-2f37-5c4e-9bfd-954ce36603f0)

Chapter 92 (#uacb76935-da95-5d66-98a1-24c9cdf6a26c)

Chapter 93 (#u3b19ed2b-1e2b-5f0a-8fa3-2769c4e68a36)

Chapter 94 (#u183282b8-f260-5543-b41b-4f070ba6a212)

Chapter 95 (#u18e04294-9a28-517c-bd66-991fb80751e8)

Acknowledgements (#u33441f3d-7f58-50ab-8825-6b0f12893c79)

Keep Reading … (#ud560a90a-2e4f-5edc-bfa9-c76ef91ccabf)

About the Author (#u179783ed-0c0f-5024-b08c-b8f94ba76391)

Also by Kate Medina (#u834324b6-dca1-53cb-877c-5c5630a12ddb)

About the Publisher (#uce8450bf-18c3-5ea4-af8b-602a35bdbed0)

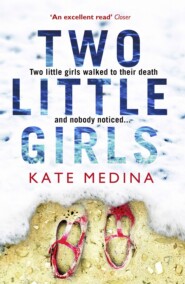

1 (#u89b70252-35f0-56c7-b7e5-c69796285993)

Though the summer holidays had ended for most, there were still a few children playing on the sand, their parents – holiday-makers, she could tell – setting out windbreaks and unpacking the colourful detritus of a family morning at the beach. Others, local mothers in jeans and T-shirts, walked barefoot with friends and dogs, keeping a roving eye on their offspring.

The sun was shining, but the air felt laden with the threat of rain and Carolynn could make out the dark trace of a sea storm hovering to the south of the Isle of Wight, misting the horizon from view. Would it rain or would the sun win out, she wondered. Would the storm come in to shore or blow out to the English Channel? Who knew; the weather by the sea, like life, so unpredictable.

Raising a hand to shade her eyes from the sunlight knifing through the clouds, she watched three little girls in pastel swimming costumes throwing a tennis ball to each other, a small dog – one of those handbag dogs she’d never seen the point of – running, yapping between them.

It was a good sign that she had brought herself to West Wittering beach this morning when she knew that families with children would be here. Evidence of her growing strength, that she could stand to watch little girls playing, listen to their shouts and their laughter.

She was healing. Except for the nightmares.

On the edge of a carefully constructed calm, aware though that her heart was beating harder in her chest – but still softly enough to ignore, and she would ignore it, she could ignore it, she wouldn’t have another panic attack, not now – she slithered down from the dunes feeling the talcum-powder sand between her bare toes, the warmth that it had soaked up from the long summer. A ball streamed past her feet, followed, seconds later, by a little girl, the youngest of the three, nine years old or so from the look of her, just a year younger than Zoe had been. She bent to pick up the ball, flicked a sandy knot of hair from her face and smiled up at Carolynn as she walked back to her sisters. Carolynn watched her go, transfixed by the shape of her body in the pale pink swimsuit; still pudgy, no waist, puppy fat padding her arms and legs – just how she remembered Zoe’s limbs, a perfect dimple behind each elbow.

She realized suddenly that the little girl had stopped, was looking back over her shoulder, pale blue eyes under blonde brows, wrinkling with concern. Carolynn forced a quick smile, felt it flicker and fade. She dragged her gaze away from the girl. She wouldn’t want her to think that there was something wrong with her, that she was anything other than a mother out for a walk on the beach, just like the little girl’s own mother. That she was someone to be feared. A danger.

Pushing off against the wet sand, each footstep leaving a damp indent behind her, Carolynn walked on towards the sea. Ever since she was a girl herself, the outside, nature, had been her escape, her way of letting her mind float free. Over these past two years she had needed its uncomplicated help more than ever before. Today of all days, she needed it desperately.

A massive hulk appeared in her peripheral vision: a ship, loaded three storeys high with a coloured patchwork of rusting steel containers, grimly industrial and incongruously man-made against the backdrop of sky and sea and the seagulls swirling overhead.

Another memory, surfacing so violently that she caught her breath at its intensity. A good memory, though. Don’t shut it out. Standing at the top of the sand dunes with Zoe, two summers ago, looking out over the Solent and watching a huge container ship glide past on its way to unload at Southampton docks. Zoe had been awed by its sheer size, a floating multi-storey tower block that the law of physics said should just turn turtle, flip upside down and be swallowed by the sea, it was so ridiculously top-heavy. The questions bursting from her without a break, words mixed up, back to front in her excitement to ask everything.

Where does it come from? Where is it going to? What’s in all those big coloured blocks on the ship, Mummy? Why don’t they all topple off into the sea? How does the ship stay upright, Mummy? Mummy? Mummy? Mummy …

Carolynn’s gaze had found the writing on the side of the ship’s hull. China Line. All the ships that cut through the Solent seemed to be from China these days.

Toys, darling.

Toys?

Zoe’s brown eyes saucer-wide, terrified she might miss the answers if she blinked for even a millisecond.

The day had been changeable, much like today. Grey clouds skipping across the sun, but still warm enough to walk in T-shirt and jeans, a cool breeze blowing in from the sea, the sand warm under their bare feet, holding the summer’s heat. The last day of their long-weekend break.

‘Can we watch the ships next time we come here?’

Reaching for Zoe’s hand, feeling the spangles of sand on Zoe’s skin grate against hers, squeezing tight, so tight. ‘Of course we can, darling. If you’re good. But you must try very hard to be good.’

They had driven back to London that night, she remembered: Zoe fast asleep in the back seat, exhausted by the fresh air, a layer of sand coating her bare legs and arms and pooled around her on the seat, as if someone had sprinkled icing sugar through a sieve; Roger miles away as he stared through the windscreen, exasperated by the weight of Sunday traffic, his mind already fixing on tomorrow’s workday.

She shouldn’t have come to the beach today. It had been a stupid mistake.

Next time.

She might go for hours with the sense that she was finally getting to grips with her grief, and then suddenly she’d be visited by a memory, an image so intense that it would take her breath away. And even the good memories hurt so badly.

Next time.

There hadn’t been a next time.

She raised her hand to her mouth, pushing back a sob. How could anyone believe that I murdered my own daughter?

2 (#u89b70252-35f0-56c7-b7e5-c69796285993)

Jessie reached for the green cardboard file of loose papers on her desk, but her fingers refused to obey the command sent from her brain, and instead of gripping the file she felt it slide from her left hand, watched helplessly as a slow-motion waterfall of papers gushed to the floor and spread across the carpet.

Shit.

She sank to her knees, feeling like a disorganized schoolkid, ludicrous, unprofessional. How the hell was a client supposed to trust her judgement when she couldn’t even persuade her useless, Judas hand to grasp a simple file? The disability constantly there, goading her. She should have stapled the papers, but she didn’t like to. Liked to be able to spread her patients’ – ‘clients’, the majority of them were called now, she reminded herself – files out on her desk, look at the pages all at once, her gaze skipping from the notes of one session to the notes of another, nothing in the human brain working in a linear fashion, so why should notes be laid out linearly, read sequentially? It made no sense.

‘Please, just sit down. I can get them myself.’ Trying to keep the edge from her voice.

‘I’m happy to help.’ The tone of the reply too bright, too jolly for such a benign statement. Everything that Laura said tinted with that Technicolor tone.

Even down here on the floor together, scrabbling to collect Jessie’s spilled papers, Laura wouldn’t meet her eye. Five sessions in and Laura had never looked her directly in the eye, not once, not even fleetingly. She wore a sober grey skirt suit and cream pussy-bow blouse, work clothes, from a life before her daughter’s accident, but Jessie noticed a fine layer of sand, like fairy dust, coating her bare feet in the sensible, low-heeled black court shoes. She had been to the beach before she came here. Outside. Nature. Jessie wouldn’t know until they started talking whether that was a good or a bad sign. Laura had told her in that first session, five weeks ago, that nature – immersing herself in nature, walking, or more often running now – since her life had changed in that one fleeting moment two years ago, was the only way she could force her mind to float free. To give up its obsessive hamster-wheel motion, if only temporarily.

Two years today, wasn’t it? September seventh? Jessie glanced down at the scattered pages, trying to find the notes from Laura’s first session to check, knowing, as she looked, that looking was unnecessary, the date cast in her memory. Seven, randomly, her favourite number. When she was a child, she used to change her favourite number every year on her birthday to match her age. At the age of seven, she had been old enough to understand that a favourite number wasn’t favourite if it changed annually, and so seven stuck. It was only when she was older that she realized she’d happened upon ‘lucky 7’. Seven days of the week, seven colours of the rainbow, seven notes on a musical scale, seven seas and seven continents.

Seven for Laura, a number forever wedded with tragedy. The day that her daughter, spotting her best friend across the road, had pulled her hand from Laura’s and been hit by a courier’s van.

Laura held out the papers she’d collected.

‘Thank you,’ Jessie said, taking them.

They rose. Clutching the file to her chest with her left arm, Jessie sat down in one of the two leather bucket chairs that she used for her sessions. She had positioned the chairs in front of the window, as the bucket chairs in her old office at Bradley Court had been positioned. No discs in the carpet yet, from their feet, to knock her sense of order off-kilter if patients nudged them out of line, the office and her life outside the army too new for such well-worn, comfortable grooves. She glanced over to the window, her gaze still trained to expect the wide-open view of lawns sweeping down to the lake, saw instead a brick Georgian terrace. Her ears, tuned to birdsong, heard the hum of traffic. The architecture was beautiful, the road narrow, quiet, but this new environment was grating all the same. Grating, Jessie admitted to herself in her more honest moments, purely because it wasn’t Bradley Court. Wasn’t her old life. A life that she hadn’t voluntarily surrendered.

She looked down at her left hand. The scar across her palm from the knife attack was still a gnarled, angry purple. Two finer, paler tracks ran perpendicular, where the surgeon had peeled back her skin to repair the severed tendons, a row of pale spots either side of the main scar where he had sewn her palm back together, each stitch identical in length and equidistant, a triumph of pedanticism, the best job that could be done, given the severity of damage to her extensor tendons, he had assured her. It still felt as if it belonged to someone else – the grotesque hand of a mannequin. Occasionally it obeyed her; more often it didn’t.

She sensed Laura watching her, looked up quickly to try to catch her eye, saw her gaze flash away.

‘We can sit at the desk, if it’s easier,’ Laura murmured.

Jessie shook her head. The barrier of the desk was too formal, too divisive for such a tense, skittish patient. ‘How was the beach?’ she asked.

‘Huh?’ Laura’s eyes, fixed resolutely on a point just to the left of Jessie’s, on a blank spot of wall, Jessie knew without needing to look, widened.

‘Sand. Your feet.’

Laura glanced down. ‘Oh, I thought you were a mind reader for a second.’ A tentative, distant smile. ‘I’d hate you to actually be able to read my mind.’

Jessie returned the smile, watching Laura’s expression, listening to the nuances in her voice. The forced jollity, like a game-show host worried for her job, always, irrespective of the subject matter.

‘So how was it?’ she prompted.

‘What?’

‘The beach?’

Laura took a moment, and Jessie noticed the apple in her throat rising and falling with the silence, as if the answer was sticking in her craw.

‘Fine … good.’

Using the oldest trick in the book, Jessie acknowledged her words with a brief nod, but remained silent. Dipping her gaze to Laura’s file, she tapped her fingers along the papers’ edges, smoothed her fingertips around the corners, perfectly aligning each sheet with the others and the edge of the file.

Laura’s voice pulled her back. ‘There were … there were children there. Girls. Little girls. Three, playing with a ball.’ Laura let out a high-pitched, nervous bark. ‘And one of those dreadful little dogs. The type that Paris Hilton carts around in a handbag.’

‘How did you feel?’ Jessie asked gently.

The apple bobbing, sticking.

‘Fine … OK.’

Jessie had learned over the five sessions not to probe too actively. The woman in front of her was tiny, blonde hair worn up in a chignon and liquid brown gazelle’s eyes made huge by the persistent dark circles under them, roving, watching – always watching, taking everything in, but never engaging. They reminded her of Callan’s eyes the first time she had met him, recently back from Afghanistan, the Taliban bullet lodged in his brain. The wary eyes of someone for whom the prospect of danger is a constant.

Laura’s file said forty-one, but she looked at least five years older than that, late, rather than early forties, every bit of the pain she had lived through etched into the lines on her soft-skinned, pale oval face.

‘The girls were, uh, sweet. They were sweet. One ran past me.’ Laura’s skeleton hand moved to cup her elbow. ‘She had dimples, here. Puppy fat—’ She broke off, the internal tension the words had created in her palpable.

‘The storm held off?’ Jessie asked, changing the subject to relieve the pressure.

‘It went out to sea. It was nice. Not hot, but warm, sunny.’

Her gaze moved from the blank wall to Jessie’s scarred left hand. It was clear from her questioning look that she wanted to know how the scars came to be there, but Jessie wasn’t willing to share personal information with a patient. She’d had colleagues who’d been burnt in the past, letting a patient cross the line from professional to personal. However much she sympathized with Laura and felt a shared history in the traumatic loss of a loved one far too young, she had no intention of making that mistake herself.

‘I have scars too.’ Laura gave a tentative smile. ‘And not just psychological ones.’ Slipping off one of her court shoes, she showed Jessie the pale lines of ancient scars running between each of her toes. ‘I was born with webbed feet, like a seagull. Perhaps that’s why I like the sea.’

They both laughed, nervous half-laughs, grateful for the opportunity to break the tension, if only for a moment. For both of them the subject – scars, psychological scars – was minefield sensitive.

‘Will it ever stop?’ Laura croaked.

What could she say? No. No, it will never stop. Your dead daughter will be the first thing you think about the second you wake. Or perhaps, if you’re lucky, the second after that. During that first second, still caught by semi-consciousness, you may imagine that she is alive, asleep under her unicorn duvet cover, clutching her favourite teddy, blonde hair spread across the pillow. But you’ll only be spared for that first second. Then the pain will hit you, hit you like a freight train and keep pace with you throughout your waking hours. This is now your life. Over time, a long time, it will lessen. One day you’ll realize that instead of thinking about her every minute, you haven’t thought of her for a whole hour. Then a day. But will it stop? No, it will never stop. Jamie never stopped, even for me, his sister. And for my mother? No, never.

‘It will fade,’ she said lamely.

Laura’s fingers had found the buckle of the narrow black patent leather belt cinching her skirt at the waist, the only thing preventing it from skidding down over her non-existent hips, the skirt having been designed for a figure ten kilos heavier.

‘It has been two years.’

‘I know.’

‘September seventh. It’s supposed to be the luckiest number in the world, isn’t it? Seven?’

Seven dwarves for Snow White, seven brides for seven brothers, Shakespeare’s seven ages of man, Sinbad the Sailor’s seven voyages, James Bond, 007.

Laura’s eyes grazed around Jessie’s consulting room, minute changes of expression flitting across her face as she absorbed the salient details: no clutter, no mess, spotlessly clean, the single vase of flowers – white tulips, Jessie’s favourite – clean and geometric, arranged so that each stem was equidistant from the next. The sunlight cutting in through the window lit tears in those liquid gazelle eyes, Jessie noticed, as her gaze flitted past.

‘Except that the bible doesn’t agree,’ Laura said.