Полная версия:

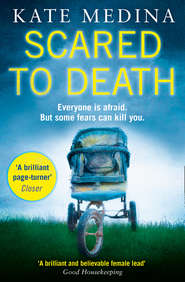

Scared to Death: A gripping crime thriller you won’t be able to put down

KATE MEDINA

Scared to Death

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street,

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Kate Medina 2017

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Cover photographs © Nikki Smith/Arcangel Images

Kate Medina asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780008132323

Ebook Edition © May 2017 ISBN: 9780008132262

Version: 2018-01-26

Dedication

For my mother, Pamela Taylor, with love

The Story of the Three Bears

ONCE upon a time there were Three Bears, who lived together in a house of their own in a wood. One of them was a Little, Small, Wee Bear, and one was a Middle-Sized Bear, and the other was a Great, Huge Bear.

Robert Southey, 1774–1843

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

The Story of the Three Bears

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Chapter 74

Chapter 75

Chapter 76

Chapter 77

Chapter 78

Chapter 79

Chapter 80

Chapter 81

Acknowledgments

Read on for an Exclusive Extract From the New Jessie Flynn Novel:

About the Author

Also by Kate Medina

About the Publisher

1

Eleven Years Ago

The eighteen-year-old boy in the smart uniform made his way along the path that skirted the woods bordering the school’s extensive playing fields. He walked quickly, one hand in his pocket, the other holding the handle of the cricket bat that rested over his shoulder, like the umbrella of some city gent. Gene Kelly in Singin’ in the Rain. For the first time in a very long time he felt nimble and light on his feet, as if he could dance. And he felt even lighter in his heart, as though the weight that had saddled him for five long years was finally lifting. Light, but at the same time keyed-up and jittery with anticipation. Thoughts of what was to come drove the corners of his mouth to twitch upwards.

He used to smile all the time when he was younger, but he had almost forgotten how. All the fun in his life, the beauty that he had seen in the world, had been destroyed five years ago. Destroyed once, and then again and again, until he no longer saw joyfulness in anything. He had thought that, in time, his hatred and anger would recede. But instead it had festered and grown black and rabid inside him, the only thing that held any substance or meaning for him.

He had reached the hole in the fence. By the time they moved into the sixth form, boys from the school were routinely slipping through the boundary fence to jog into the local village to buy cigarettes and alcohol, and the rusty nails holding the bottom of the vertical wooden slats had been eased out years before, the slats held in place only at their tops, easy to slide apart. Nye was small for his age and slipped through the gap without leaving splinters or a trace of lichen on his grey woollen trousers or bottle green blazer, or threads of his clothing on the fence.

The hut he reached a few minutes later was small and dilapidated, a corrugated iron roof and weathered plank walls. It used to be a woodman’s shed, Nye had been told, and it still held stacks of dried logs in one corner. Sixth formers were the only ones who used it now, to meet up and smoke; the odd one who’d got lucky with one of the girls from the day school down the road used it for sex.

Nye had detoured here first thing this morning before class to clean it out, slipping on his leather winter gloves to pick up the couple of used condoms and toss them into the woods. Disgusting. He hadn’t worried about his footprints – there would be nothing left of the hut by the time this day was over.

Now, he sprayed a circular trail of lighter fuel around the inside edge of the hut, scattered more on the pile of dry logs and woodchips in the corner, ran a dripping line around the door frame and another around the one small wire-mesh-covered window. Tossing the bottle of lighter fuel on to the stack of logs, he moved quietly into a dark corner of the shed where he would be shielded from immediate view by the door when it opened, and waited. He was patient. He had learned patience the hard way and today his patience would pay off.

Footsteps outside suddenly, footsteps whose pattern, regularity and weight were seared into his brain. Squeezing himself into the corner, Nye held his breath as the rickety wooden door creaked open. The man who stepped into the hut closed the door behind him, pressing it tightly into its frame as Nye knew he would. He stood for a moment, letting his vision adjust to the dimness before he looked around. Nye saw the man’s eyes widen in surprise when he noticed him standing in the shadows, when he saw that it wasn’t the person he had been expecting to meet. His face twisted in anger – an anger Nye knew well.

Swinging the bat in a swift, neat arc as his sports masters had taught him, Nye connected the bat’s flat face, dented from contact with countless cricket balls on the school’s pitches, with the man’s temple. A sickening crunch, wood on bone, and the man dropped to his knees. Blood pulsed from split skin and reddened the side of his face. Nye was tempted to hit him again. Beat him until his head was pulp, but he restrained himself. The first strike had done its job and he wanted the man conscious, wanted him sentient for what was to come.

Dropping the cricket bat on to the floor next to the crumpled man, Nye pulled open the shed door. Stepping into the dusk of the woods outside, he closed it behind him. There was a rusty latch on the gnarled door frame, the padlock long since disappeared. Flipping the latch over the metal loop on the door, he stooped and collected the thick stick he’d tested for size and left there earlier, and jammed it through the loop.

Moving around to the window, too small for the man to fit through – he’d checked that too; he’d checked and double-checked everything – he struck a match and pushed his fingers through the wire. He caught sight of the man’s pale face looking up at him, legs like those of a newborn calf as he tried to struggle to his feet. His eyes were huge and very black in the darkness of the shed. Nye held the man’s gaze, his mouth twisting into a smile. He saw the man’s eyes flick from his face to the lit match in his fingers, recognized that moment where the nugget of hope segued into doubt and then into naked fear. He had experienced that moment himself so many times.

He let the lit match fall from his fingers.

Stepping away from the window, melting a few metres into the woods, Nye stood and watched the glow build inside the hut, listened to the man’s screams, his pleas for help as he himself had pleaded, also in vain, watched and listened until he was sure that the fire had caught a vicious hold. Then he turned and made his way back through the woods, walking quickly, staying off the paths.

It was 13 July, his last day in this godforsaken shithole.

He had waited five long years for this moment.

Thirteen. Unlucky for some, but not for me. Not any more.

2

Twelve Months Ago

He had thought, when the time came, that he would be brave. That he would be able to bear his death with dignity. But his desperation for oxygen was so overwhelming that he would have ripped his own head off for the opportunity to draw breath. He sucked against the tape, but he had done the job well and there were no gaps, no spaces for oxygen to seep through. Wrapping his hands around the metal pipe that was fixed to the tiled wall, digging his nails into the flaking paint, he held on, willing himself to endure the pain, knowing, whatever he felt, that he had no choice now anyway.

Closing his eyes, he tried to draw a picture to mind, a picture of his son, of his face, but the image was lost in the screaming of blood in his ears, the throbbing inside his skull as his brain, his lungs, his whole being ballooned and burst with its frenzied need for oxygen. He felt fingers clawing at his temples. But he had wrapped the gaffer tape tight, layer upon layer of it round and round his head, and his own fingernails, chewed and ragged, couldn’t get purchase.

His lungs were burning and tearing, rupturing with the agony of denied breath.

The room was fading, the feel of his scrabbling fingers numbing. His brain fogged, his limbs were leaden and the pain receded. Danny’s eyes drifted closed and he felt calm, calm and euphoric, just for a moment. Then, nothing.

3

Nobody noticed the pram tucked against the wall inside the entrance to Accident and Emergency at Royal Surrey County Hospital, until the baby inside woke and began to cry. It was another ten minutes before the sound of the crying child registered in the stultified brain of the A & E receptionist who had been working since 11 p.m. the previous night and was now wholly focused on watching the hands of her countertop clock creep towards 7 a.m. and the end of her shift. The ‘zombie shift’, nights were dubbed, both for their obliterating effect on the employee and in reference to the motley stream of patients who shuffled in through the sliding doors. The past eight hours had been the busiest she could remember. Dampness she expected in April, but constant downpours combined with unseasonal heat were a gift to unsavoury bugs. Back-to-back registrations all night, not enough time even to grab a second coffee, and now her nerves, not to mention her temper, were snapping. At fifty-five she was too old for this kind of job, should have taken her sister’s advice and become a PA to a nice lazy managing director in some small business years ago.

She had noticed the pram – she had – she would tell the police when they interviewed her later, but she had assumed that it had been parked there, empty, by one of the parents who had taken their baby into Paediatrics. It had been a reasonable assumption, she insisted to the odd-looking detective inspector, who had made her feel as if she was responsible for mass murder with that cynical rolling of his disconcertingly mismatched eyes. The wait in Paediatric A & E on a busy night was five hours, so it was entirely reasonable that an empty pram could be parked in the entrance for that long. God, at least she didn’t turn up for work looking as if she’d spent the night snorting cocaine, which was more than could be said for him.

Skirting around the desk, she approached the pram, the soles of her Dr Scholl’s sighing as they grasped and released the rain-damp lino. Her stomach knotted tightly as she neared it, recent staff lectures stressing the importance of vigilance in this age of extremism suddenly a deafening alarm bell at the forefront of her mind. But when she peeped inside the pram, she felt ridiculous for that moment of intense apprehension. She breathed out, her heart rate slowing as the tense balloon of air emptied from her lungs.

A baby boy, eighteen months or so he must be, dressed in a white envelope-neck T-shirt and sky-blue corduroy dungarees, was looking up at her, his blue eyes wide open and shiny with tears. Wet tracks cut through the dirt on his cheeks. His mouth gaped, lips a trembling oval, as if he was uncertain whether to smile or cry, four white tombstone teeth visible in the wet pink cavity.

Reaching into the pram, Janet gently scooped him into her arms. Nestling him against her bosom, she felt the chick’s fluff of his hair, smelt the slightly stale, milky smell of him, felt the bulge of his full nappy, straining heavy in her fingers as she slid her hand under his bottom to support his weight. The child gave a sigh and Janet felt his warm body relax into hers.

‘Now who on earth would leave a little chap like you alone for so long?’ she cooed softly. ‘Who on earth?’

How long since she’d held a baby? Years, she realized, with a sharp twinge of sadness. Her youngest nephew fifteen now and already on to his fourth girlfriend in as many months, her own son, nearing thirty, had fled the nest years ago.

She turned back to the reception desk, all efficiency now. ‘Robin, get on the tannoy would you and make an announcement. Some irresponsible fool has left their baby out here and he’s woken up. Probably needs feeding.’ She looked down at the baby. ‘Don’t you worry, sweetheart. We’ll find your mummy and get you fed.’ She tickled his cheek with the tip of her index finger. ‘We will. Yes, we will, gorgeous boy.’ Glancing up, she met Robin’s amused gaze. ‘What? What on earth are you smirking about?’

4

Jessie woke with a start and opened her eyes. The room was dark, the air dusty and stale, a room that hadn’t been aired in months. She felt dizzy and nauseous, as if her brain was slopping untethered inside her skull, her tongue a numb wad of cotton filling her mouth. Once again, the man’s voice that had woken her spoke from close by. For a brief moment, caught in that twilight zone between sleep and wakefulness, she had no idea where she was. Which country. Which time zone.

‘Some folk tales – or fairy tales as we like to call them nowadays – originated to help people pass on survival tips to the next generation. Many of the stories that we now tell our children at bedtime were based on gruesome real events and would have served as warnings to young children not to stray too far from their parents’ protection.’

The radio. Of course. She had left it on when she went to bed last night, used now to being lulled to sleep by noise. The groan of metal flexing on waves, footsteps pacing down corridors, machines humming in distant rooms.

Home. She was home, she realized as cognizance overtook her. Back in England, waking in her own bed for the first time in three months.

‘Over the years these stories have changed, evolved to suit the modern world. Even though humans are as violent nowadays as they were in 600 BC, we don’t like to terrify our children in the same way that our ancestors did, so we sugar-coat fairy tales. But their horrific origins and the messages behind them are deadly serious.’

She had flown into RAF Brize Norton airbase late last night, arrived home at 2 a.m. – 5 a.m. Syrian, Persian Gulf, time – and collapsed into bed, exhausted, jet-lagged, struggling to adjust not only her body clock but her brain from Royal Navy Destroyer to eighteenth-century farmworker’s cottage in the Surrey Hills, a juxtaposition so complete that she had felt as if she was tripping on acid. Washed out from months of shuttling between RAF Akrotiri in Cyprus and the HMS Daring, counselling fighter jet and helicopter pilots flying sorties over ISIS-held territory in Syria and Iraq, working with PsyOps to see how they could win hearts and influence minds in the region. Unused to the impenetrable darkness and graveyard silence of the countryside, she had, for the first time in her life, flipped the radio on, volume turned low, background noise, and fallen asleep to its soft warble.

On the radio, the man’s voice was rising. ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarves is based on the life of a sixteenth-century Bavarian noblewoman, whose brother used small children to work in his copper mines. Severely deformed because of the physical hardships, they were referred to as dwarves. ‘We know that Little Red Riding Hood is about violation, a young girl allowing herself to be charmed by a stranger. The contemporary French idiom for a girl having lost her virginity is “Elle avoit vu le coup”, which translates literally as “She has seen the wolf”.’

Reaching an arm out, Jessie jammed her finger on the ‘off’ switch. Silence. Not even birdsong; too early yet for the dawn chorus. Curling on to her side, she closed her eyes and tugged the duvet up around her ears, trying to tilt back into sleep. But she was awake now, her mind a buzz of jetlag-fuelled, pent-up energy. May as well get up and face the day.

Throwing off the duvet, she padded into the bathroom to have a shower, catching her reflection in the huge mirror above the sink that she had erroneously thought it a good idea to install after reading a home décor magazine at the dentist that had waxed lyrical about mirrors opening up small spaces. The harsh electric ceiling lights, another poor idea – same magazine – washed the face looking back at her ghostly grey-white, blue eyes so pale they were nearly translucent, black hair limp and unkempt, a cartoon version of Snow White with a stinking hangover. Jesus, Jessie, only you could spend twelve weeks in the Middle East and still come back looking as if you’ve been bleached. Coffee was the answer, and lots of it.