Полная версия:

Asthma-Free Naturally: Everything you need to know about taking control of your asthma

Asthma-Free Naturally

Everything you Need to Know to Take Control of your Asthma

Patrick McKeown

‘Without mastering breathing, nothing can be mastered.’

– P.D. Ouspensky

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Epigraph

Introduction

Chapter 1 Asthma for beginners

Chapter 2 How is your breathing?

Chapter 3 Taking control

Chapter 4 Make correct breathing a habit

Chapter 5 Breathe right during physical activity

Chapter 6 Food that helps, food that hurts

Chapter 7 What’s your trigger?

Chapter 8 Know your medication

Chapter 9 How to help children and teenagers

Chapter 10 Individual and national goals

Appendix 1 Hyperventilation

Appendix 2 Hyperventilation and asthma

Appendix 3 Controlled Buteyko trials 1995/2003

Appendix 4 House of commons debate

Appendix 5 Konstantin Pavlovich Buteyko

Appendix 6 Useful addresses

References

Diary of Progress

Index

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

This book teaches you how to take control of your asthma safely and effectively without any side effects. The approach encompasses the Buteyko Clinic Method and instruction on diet, sleeping, physical activity and other lifestyle factors. I had chronic asthma for twenty years but since making these changes to my lifestyle, I have been completely asthma free.

The Buteyko (Bhew-tae-ko) Clinic Method is recognised by the Russian medical authorities. Not alone that, but it has been backed up by two independent scientific trials held in the Western world. The method has received widespread attention including a detailed debate in the UK House of Commons in July 2001. Evidence from thousands of people worldwide – who improved their lives forever by applying Buteyko breathing exercises – is also available.

This non-medical treatment is based on the life’s work of Russian respiratory physiologist, Professor Konstantin Buteyko, who developed a programme of exercises to foster correct breathing. The Buteyko Clinic Method is based on bodily processes and not on a placebo effect.

There are three ways of controlling asthma. The first and most important is learning to breathe through the lungs’ natural defence – the nose – combined with correct breathing. The second is living a life balanced by proper nutrition, regular exercise and relaxation. The third avenue is using preventative and relieving asthma medication.

Think of it as a three-way junction where you, the person with asthma, can choose the direction. The first two avenues are like the scenic routes: they’re entirely natural, proven and improve overall health, but require personal commitment and an investment of time and energy. The third avenue is the one most often travelled by people like you but it never addresses the root cause of your breathing problem. The third avenue also involves taking chemicals which are alien to your body. Sooner or later, your body fights back or submits to the continuous use of powerful drugs.

I’m often told that people with asthma are fortunate to have such a wide range of medication available to them now, and I agree. We are fortunate. However, as a person with asthma myself, I feel that being dependent on medication for survival generates feelings of weakness and vulnerability. That being said, I always stress to my patients that medication, especially preventer medication, is very important, but that they should take enough to maintain control – no more and no less. Likewise, I advise patients to try to avoid situations that are likely to trigger an attack.

I was diagnosed with asthma as a child, a condition that worsened as I grew older until I discovered Buteyko Breathing through a newspaper article. I learned as much as I could, self-taught the techniques, and found myself gradually reducing the amount of medication I had to take to control my asthma.

When I experienced the impressive benefits of the Buteyko Method, I wondered why more people didn’t know about it or how to apply it to their own lives. I decided to explore the possibility of training so that I could teach this beautiful and simple method to asthma sufferers like myself. I found out that I could enrol at the Buteyko Clinic of Moscow and, after many trials and tribulations, I started my training under Dr Andrey Novozhilov and Dr Luidmilla Buteyko. The Buteyko Clinic of Moscow was founded by Professor Konstantin Buteyko as a centre for the treatment and prevention of health problems. The Buteyko Clinic Method is used to describe the programme of breathing exercises as taught by the Buteyko Clinic of Moscow.

I was accredited by Professor Buteyko in March of 2002, and since this time, the knowledge I gained in Moscow has been complemented by my own research, by consulting with asthma specialists from different parts of the world, and by ongoing client contact throughout Ireland.

The simple question is: does it work? In a word: yes. Some patients achieve excellent results effortlessly, but with others it takes a little more time and determination. The success of this therapy for every patient depends on the patient’s ability to put the theory into practice. There is no big mystery – this therapy is based on normal body processes. Scientific trials have shown clearly that the Buteyko Method can be one hundred per cent effective in the treatment of asthma.

The only real key to the effectiveness of the therapy is that individuals are prepared to set aside the necessary time to learn and practice the exercises.

I commend those of you who, on reading this book, will decide to make that effort. I can honestly say that your investment of time and energy will be gratifying, and that it will transform your life…for the rest of your life.

I can hear you thinking that there’s no such thing as a free lunch, and that there’s always a catch. There is no catch this time. Once you learn how to control your own asthma, you are in charge of your own life and treatment. This therapy is about teaching you the skills to deal with your own asthma problem; my job is essentially to make myself redundant.

This book, written by a person with asthma for people with asthma, contains essential information to help you deal with your condition. Each exercise is a simplified version to make the contents as user-friendly as possible in the hope that you will be able to understand and appreciate this approach, and that you will be able to apply it practically to your own asthma problem.

Included is a special section for children who naturally will have difficulty understanding breathing patterns. Every child who comes to me is told how lucky he or she is to be learning a therapy as effective as this, a therapy that deals with what otherwise would be a life-long illness…without medicine, tablets, hospital visits or injections.

At our clinics throughout the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, patients receive practical help and advice and our training exercises are designed to suit the individual needs of each person. My clinics also address lifestyle factors such as correct breathing during physical activity, diet, sleeping, stress and much more. Clinics are a very useful way of exchanging information and answering any questions participants may have.

Feedback from those who attend our clinics has been extremely helpful in furthering my own knowledge of asthma, in developing the content of future clinics, and also in the writing of this book.

There’s another simple question you may have at this point: why is the Buteyko method not better known? That’s a good question, and one to which I don’t have a clear answer. Looking at the current situation openly, however, one of the most striking features is that medical research is mainly funded by pharmaceutical companies, in one form or another. Asking the pharmaceutical industry to fund research into a method such as Buteyko – with its non-medication approach – is perhaps like asking turkeys to vote in favour of Christmas. The usual answer is that there has been insufficient research for authoritative judgements to be made.

If a non-medication approach to asthma such as the Buteyko Method achieved widespread acceptance in Ireland, there would be massive savings in the national health budget. Given the potential for savings, the Department of Health should be interested in commissioning or supporting research into the method. To date, there has been no indication of any awareness of this potential by the Department.

My main aim is to help people overcome their asthmarelated problems by using the Buteyko Clinic Method and lifestyle changes. When enough people have experienced the benefits, I hope that public opinion might have enough leverage on medical authorities to encourage them to assess Professor Buteyko’s method with an open mind. If that happens, then at least there will be a long-delayed debate on the subject.

I am open to any comments, suggestions or criticism which you may have regarding this book. Constant feedback from my patients has already improved my understanding of asthma and my ability to help people.

All this therapy involves is a commitment to observation of breathing and practice of simple breathing exercises, plus a reasonably well-balanced lifestyle. The reward is freedom. The prize is freedom from asthma.

I wish you every success in applying this tried and tested method developed by an extraordinary Russian doctor.

Patrick McKeown BA MA (TCD) Dip. Buteyko (Moscow)

Chapter 1 Asthma for beginners

‘No matter what treatment you avail of and no matter what medications you take for your asthma, as long as you continue to overbreathe, you will continue to have asthma.’

This book is about taking control of your asthma safely and without the need for medication. You will read about how I transformed myself from an acute asthmatic with a permanent illness requiring daily drug intake – and hospitalisation from time to time – to a virtual non-asthmatic who is totally free from asthma symptoms, attacks…and medication.

You may not believe that this scenario is real. It is. I achieved it and any asthmatic can achieve it too. This non-medical treatment is based on the life’s work of Russian respiratory physiologist, Professor Konstantin Buteyko, who developed a programme of exercises to foster correct breathing. The Buteyko Method is based on bodily processes, not on a placebo or any other effect. All persons with asthma can learn it and use it; the method is very simple, will entail minimum disruption to your life, and you will notice an improvement in as little as seven days. Like I said, you still may not believe this scenario is real. Believe it now.

Asthma was diagnosed when I was very young. Initially my condition was mild and consisted of just occasional wheezing and breathlessness. The treatment consisted of using an Intal inhaler. I only had an attack occasionally, so my asthma didn’t really disrupt my life.

When I reached the age of ten, my asthma deteriorated a little so I was prescribed a Ventolin inhaler which guaranteed me immediate relief from the symptoms. I had to take a Uniphyiulum tablet each night as well. At the time, just one puff of Ventolin dealt with any breathing difficulty I experienced. My asthma was under control.

With the best of intentions, our doctor told my mother that children with asthma very often ‘grow out of it’ during their teenage years. Time and time again, I was assured that this should happen, and it offered a ray of hope for me, but this hope was never realised. As I grew into adulthood, the dose needed to maintain control of my asthma increased. One puff of Ventolin per day was no longer enough. Soon I was taking two, five, eight and even ten puffs a day. My lifestyle during my school and college years didn’t help, but I had my Ventolin inhaler to help me overcome any problems so I wasn’t too concerned about it.

One weekend, when I was in my early twenties, I was brought to James Connolly Memorial Hospital with an asthma attack, and I was told that I was being treated for acute asthma. Two weeks of large doses of oral steroids later, I returned home.

As the years passed, the amount of medication I needed continued to increase. There was no great discussion about this with my doctor, nor any indication that the amount of drugs I needed would ever decline. It seemed to me that I was going steadily downhill, and I became gradually more concerned about the effect that the increasing levels of medication might be having on my general health and well-being.

Many people with asthma can relate to this summary of the steady progression of the condition. What starts off as an occasional wheeze soon develops into continuous symptoms; while one puff of medication deals with symptoms in the early stages, dependency on medication increases remorselessly.

Over time, my asthma developed into a seriously debilitating condition that prevented me from taking part in sport and outdoor activities. I always avoided opportunities to play a match or work out in the gym. The physical limitations were one thing, but the stigma attached to me because of my asthma was another. I had ‘weak lungs’, and I was not as physically strong as lads of my age. Initially, when I was very young, I thought it was cool to carry an inhaler – it was a neat gadget that made me different – but as I got older it labelled me in a way I didn’t like. When I realised this, in the succeeding years I always tried to take my inhaler when there was no-one else around, for all the world like a secret drinker.

While I grappled with the daily realities of having asthma, there were two unanswered questions at the back of my mind. When is this ever going to stop? Why am I so inadequate that I have to take daily doses of drugs merely to function normally? I was turning myself into a victim, but these are common questions that will be familiar to many asthma sufferers. The questions may not be voiced openly because complaining will do little to change what may seem like an unalterable reality, but they are still very real concerns.

The first indication I had that there was a viable alternative to taking a Ventolin inhaler in secret arrived in my early twenties, when I happened upon an article in the Irish Independent newspaper about a breathing therapy developed by a Russian professor which seemed to be effective in helping people with asthma. Over the years, I had already tried acupuncture, Chinese herbs, deep-breathing exercises and indeed any other therapy that I felt might help. When Buteyko Breathing was featured in a magazine article shortly afterwards, I decided to find out more.

I started my search for knowledge by contacting Buteyko practitioners from around the world via the Internet. I learned as much as possible about the application of the therapy and I purchased the limited publications and videos available at the time. I taught myself the technique, used it intensively, and I was pleasantly surprised at the rapid effect it had on my asthma. Intuitively, I felt that I understood the significance of Professor Buteyko’s work…even before I began applying it.

In a matter of months, my asthma improved so dramatically that I could reduce my medication intake significantly. As my condition continued to improve and my medication intake continued to decrease, I felt that for the first time in my life my asthma was under control. The bonus for me was that I had achieved this myself. My days of secretly puffing Ventolin were behind me.

Elixir of life

Take a breath now, and think about it carefully. Breathing is the elixir of life. More than that, breathing is life. We humans can live without water for days and without food for weeks, but we cannot live without air for more than a few minutes. Think about how we Westerners view food and water: we know that the quantity and quality of food and water we consume determines our state of health. We know that having too little means starvation or dehydration, and that too much leads to obesity and other health problems.

Why then does the quantity and quality of our breathing receive so little attention? Surely breathing, which is so immediately essential to life, must meet certain conditions? Why have other cultures, particularly in the Eastern world, recognised the importance of correct breathing to health for thousands of years, when we clearly don’t?

What is asthma?

There is no universally accepted definition of asthma. The Concise Oxford Dictionary describes it as ‘a disease of respiration characterised by difficult breathing, cough etc.’. Any good medical book will describe it in more technical terms but ‘difficult breathing’ is the part with which any asthma sufferer is familiar, even if it varies from mildly uncomfortable to life-threatening. Asthma is news now. There was a dramatic increase in the condition in the late twentieth century to the extent that an estimated 100 to 150 million people in the world are now affected by it, but it is not a recent phenomenon.1

The term ‘asthma’ is a Greek translation of gasping or panting, and the problem was treated as far back as 2000 BC by Chinese doctors with the herb Ma Huang. The first known recording of the symptoms was about 3,500 years ago in an ancient Egyptian manuscript called Ebers Papyrus. Throughout the ages, asthma has received varying degrees of attention; the symptoms and their accompanying anxiety have been described by many prominent historical figures, including the famous Greek physician, Hippocrates.

Over the centuries, there has been an assortment of different theories about the causes of asthma, and so an eclectic range of remedies has been advised, including horse riding, strong coffee, tobacco, faith healing, chloroform and even drinking the blood of owls in wine, as practised by the ancient Romans. Van Helmont who lived in the early part of the seventeenth century claimed that asthma was epilepsy of the lungs due to the sudden and unpredictable nature of an attack. Based on his own experience of asthma, English physician Thomas Willis said that ‘the blood boils’, and that ‘there is scarce anything more sharp or terrible than the fits thereof ’.

It was not until the eighteenth century that Lavoisier provided the first real account of the functioning of the lungs, thereby providing the basis of modern-day understanding of the respiratory system. Prior to this, it was commonly believed that air was drawn into the lungs to cool the body. Lavoisier’s contribution was that air is drawn in to be converted to energy by the metabolism, and that carbon dioxide and heat are produced as end products of the process. Lavoisier’s work recognised that oxygen is essential to sustaining life.

Asthma now affects more people throughout the world, particularly in more developed countries, than at any other time in evolution. It inflicts greater economic and social damage in Western Europe than either TB or HIV, according to the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) April 2002 report on the links between ill health in children and the deteriorating environment.

The position in selected developed countries may be summed up as follows (all figures are approximate):

According to the 1998 International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC), the countries with the highest twelve-month incidence of asthma were the UK, Australia, New Zealand and the Republic of Ireland followed by North, Central and South America. The same report found that the lowest rates were in centres in several Eastern European countries, followed by Indonesia, Greece, China, Taiwan, Uzbekistan, India and Ethiopia. Other studies show that the rate of asthma among rural Africans who migrate to cities and adopt a more ‘western’ urbanised lifestyle increases dramatically. According to the UCB Institute of Allergy in Belgium, the incidence of asthma in Western Europe has doubled in the last ten years.1

In the Western world, asthma crosses all class, race, geography and gender boundaries. Although it causes persistent symptoms among seventy per cent of all people diagnosed with it, asthma causes only minor discomfort to the majority. In fact, some of the most influential people of our time in all walks of life were asthmatic, including Russian Tzar Peter the Great, actors Liza Minnelli, Jason Alexander and Elizabeth Taylor, revolutionary Che Guevara, and former US presidents John F Kennedy, Calvin Coolidge and Theodore Roosevelt. All these have lived life to the full or are still living it.

What are the symptoms?

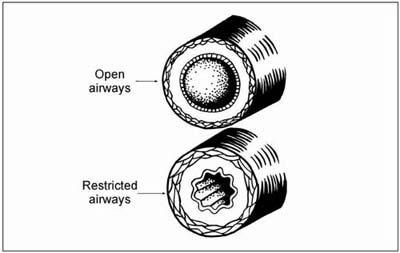

So what is asthma and what are the symptoms? The condition consists of inflammation, tightening and swelling of the airways in the respiratory system, resulting in obstruction of the flow of air to and from the lungs. The symptoms of asthma include breathlessness, wheezing, coughing and chest tightness. Sufferers may also have a blocked nose, frequent colds and hay fever, or rhinitis. The symptoms and their severity are peculiar to the individual, and they vary from season to season and according to the individual’s susceptibility to a wide range of triggers.

An ‘asthma attack’ is the term used to describe an episode of breathing difficulty. In some cases, this may follow exposure to a specific trigger, such as dust, pollen, or certain

Airways narrowing

foods. In other cases there appears to be no particular trigger. Some people have a cough and no wheeze, while others may have a wheeze and very little coughing, but each case is accompanied by some level of breathing difficulty. Symptoms may occur periodically, on a day-to-day or season-to-season basis, or they may be more or less continuous.

A ‘trigger’ is something that makes asthma worse. The most common triggers include (in alphabetical order): allergies; cigarette smoking (and cigarette smoke for nonsmokers); colds and flu; cold air; dust mites; exercise under certain circumstances; moulds; noxious fumes; pollens; stress, and weather types such as fog and damp. In some instances an asthma attack may be triggered by a combination of catalysts. Anxiety can be caused by the variations on the asthma theme, particularly where a child is involved. Sometimes, there may be confusion between doctor and patient when a diagnosis is being made.

There is also a wide variety in the symptoms of asthma. The following is a list of those most commonly experienced by sufferers.

♦ Wheeze

This is a high pitched whistling sound produced when air is forced through narrowed airways. If you blow through a Biro pen when the ink refill is removed, the sound is similar.

♦ Breathlessness

This is the feeling of not being able to take in enough air. There is a need to breathe out while, at the same time, a compulsion to breathe in. If this symptom develops to an extreme level it can be frightening for the sufferer and very distressing for those close to him or her.