Полная версия:

So Many Ways to Begin

So Many Ways to Begin

Jon McGregor

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

First published by Bloomsbury in 2006

This eBook published by 4th Estate in 2017

Copyright © 2006 by Jon McGregor

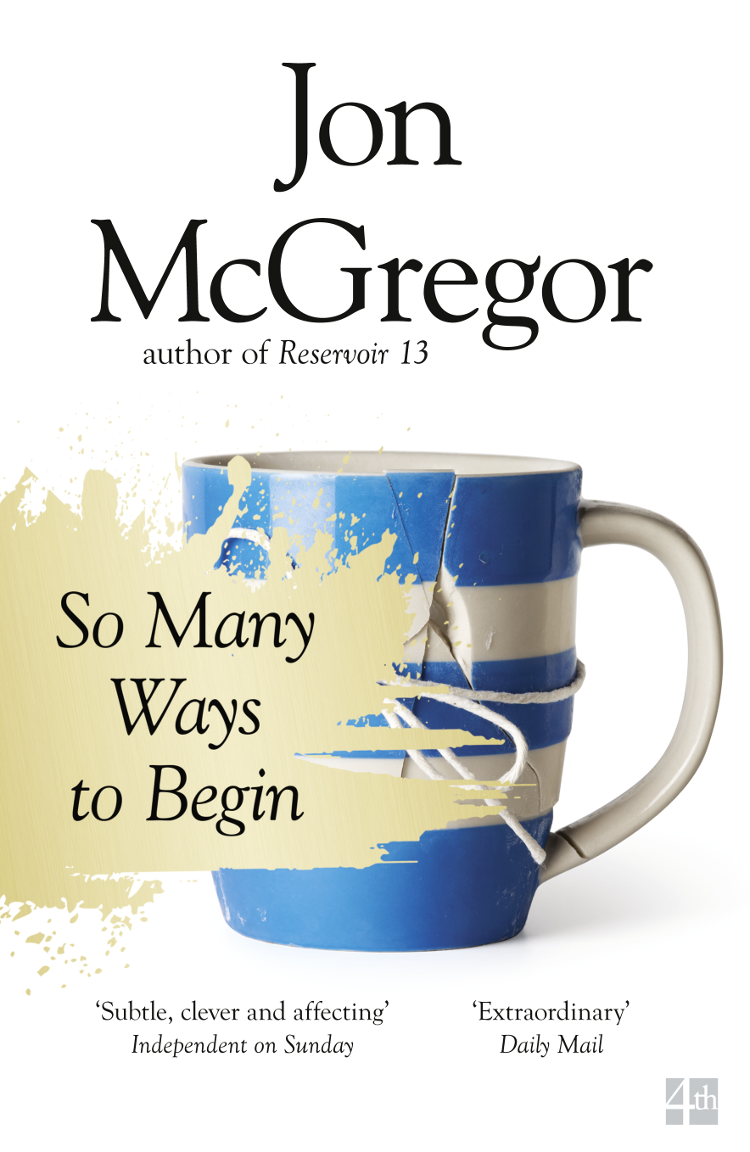

Cover image © Mat Taylor

Jon McGregor asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008218676

Ebook Edition © January 2017 ISBN: 9780008218683

Version: 2016-12-07

Further praise for So Many Ways to Begin:

‘So Many Ways to Begin confirms his reputation … Beautifully written’

Irish Times

‘Both triumphant and almost unbearably moving’

Waterstone’s Books Quarterly

‘McGregor’s talent remains dazzlingly apparent … McGregor captures in near-poetry what it is to lose our beginnings and to recreate a past’

Scotland on Sunday

‘McGregor’s gift is in finding the extraordinary in everyday life, subtly invoking your empathy with utterly believable characters’

Eve Magazine

‘The writing is powerfully spare and unadorned … an immensely sympathetic portrait of a marriage’

Time Out

‘Beautifully poetic’

Observer

‘His work has been compared to Philip Larkin in the way that it draws on a certain monochrome Englishness but the colour and poetry of his writing brings a luminous depth to his subject’

Metro

‘I absolutely loved this book’

Mariella Frostrup

‘A tender and invigorating picture of domestic life drawn by a masterly hand’

Big Issue

‘Compelling and convincing. A deeply rewarding read’

Good Book Guide

‘A very fine, affecting work that moves gracefully towards an unforgettable conclusion’

Glasgow Herald

‘It is a heartbreaking, luminous and wonderful work … He is an accomplished author who writes with blinding insight. One of the best books of 2006’

Shropshire Star

To Alice

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Further praise for So Many Ways to Begin

Dedication

Part One

1 b/w photograph, Albert Carter, defaced, c.1943

2 Handwritten list of household items, c.1947

3 Local Map, Whitechapel district, London, annotated, c.1950

4 Tobacco tin, cigarettes, Christmas card, 1914

5 Shoebox of assorted domestic goods, bullets, shrapnel, 1953–1960

6 Postcard from Greenwich Maritime Museum, c.1953

7 Opening programme, Coventry Municipal Art Gallery and Museum, 1961

8 Two telegrams, November 1939 and April 1940

9 Contract, wage slip, duty sheet, from Coventry Museum, 1964

10 Letters, handwritten, 1966–68; Paper Napkin, 1966

11 Cigarette holder, tortoiseshell, believed 1940s

12 Picture postcard, Union Street, Aberdeen, c.1966

13 Pocket appointment diaries (incomplete set), dated 1935–1959

14 Pair of letters, handwritten, February 1967

15 Picture postcard, John Lewis shipyard, Aberdeen c.1967

16 Birth Certificate, 17 March 1945

Part Two

17 Pair of cinema tickets, annotated ‘19th May 1967’

18 Disciplinary letter, typewritten on headed paper, January 1968

19 Identity badge, Junior Curatorial Assistant, Coventry Museum, W/Photo, 1967

20 Examination results, Scottish Highers, July 1967

21 Train ticket, Aberdeen–Coventry (Single), 15 September 1968

22 Book of Co-op dividend stamps, 1968

23 Handwritten list of coventry addresses, August 1968

24 Doorkey on a knotted loop of string; Wedding certificate, October 1968

25 Lacework placemats (wedding gift), 1968

26 Geologist’s rock-hammer, in original case (wedding gift, unused), c.1969

27 Model fishing boat, handmade c.1905

28 Page torn from Aberdeen Press & Journal, crumpled, August 1968

29 Set of clothes pegs, traditional style, w/hand-drawn faces, c.1920s–1950s

30 Girl’s hairbrush, wooden-handled, c.1940s

31 Nurse’s fob watch, engraved RCN, 1941

32 University prospectuses; 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1974

33 Pill bottles, prescriptions; dated variously 1973–1987

34 Small vase, handmade by unknown Warwickshire potter, 1974

35 Tobacco tin; used for storing buttons, beads, safety pins, c.1960s

36 Catalogue from museum exhibition, ‘Refugees, Migrants, New Arrivals’, 1975

37 Framed photograph (w/broken glass), David and Eleanor, c.1975

38 Wine cork, dated (handwriting) August 1975

39 Hospital admissions card, 1945 (Discovered 1976)

40 Scrapbook w/postcards, tickets, maps, etc., 1979

Part Three

41 Cut fragments of surgical thread, in small transparent case, dated July 1983

42 Pocket address book, w/page torn out, c.1982

43 Small fragment of metal, unidentified, 1983

44 Pair of child’s gloves, striped, c.1983

45 Job application form, Head Curator, c.1984

46 Hand-drawn family tree (incomplete), dated May 1984

47 Envelopes w/Aberdeen postmarks, occasional 1984–2000

48 Photographs of Kate at eight years old, with birthday cards, 1984

49 Library tickets, green card with handwritten annotations, c.1980s

50 DHSS Booklet, Guide to Services for the Newly Unemployed, 1986

51 Video cassette: World’s Greatest Boxing Heroes, c.1987

52 Hand-drawn family tree, marked ‘Believed Complete’, dated 1988

53 Home videos featuring Kate Carter, 1991–1994

54 Examination results; University prospectus, 1994

55 Illustrated Book of Knots, 7th Edition, c.1947

56 Ration books, Union cards, Co-op dividend stamps, 1930s and 1940s

57 Printed service sheet, ‘Ivy Elaine Campbell, 1910–2000’, 23 April 2000

58 Email messages; printed copies dated March 2000

59 Ferry tickets; handwritten letter; route map (from website); all June 2000

60 Biscuit tin, rusted, used as money box or for keepsakes, c.1944

61 Paper package of selected photographs (reprints), c.1950–2000

62 Bill for room and board, Conway’s of Letterkenny, June 2000

Acknowledgements

Read an exclusive extract from Jon McGregor’s new novel, Reservoir 13

By the Same Author

A Note on the Author

About the Publisher

They came in the morning, early, walking with the others along tracks and lanes and roads, across fields, down the long low hills which led to the slow pull of the river, down to the open gateways in the city walls, the hours and days of walking showing in the slow shift of their bodies, their breath steaming above them in the cold morning air as the night fell away at their backs. They came quietly, the swish of dew-wet grasses brushing against their ankles, the pat and splash of the muddy ground beneath their feet, the coughs and murmurs of rising conversation as the same fewphrases were passed back along the lines. Here we are now. Nearly there. Just to the bottom of the hill and then we’ll sit down. Cigarettes were lit, hundreds of cigarettes, thin leathery fingers expertly rolling a pinch of tobacco into a lick of paper without losing a step. Cigarettes were cadged, offered, shared, passed down to nervous young hands eager for that first acrid taste of adulthood, cupping a mouthful of it in the windshield of their open fists in imitation of fathers and uncles and older brothers, coughing as it burnt down into their untested young lungs, the spluttered-out smoke twisting upwards and mingling with their cold clouded breath as they made their way between flowering hawthorn hedges and cowslip-heavy banks, down towards the city walls. They wore suits, of a kind, all of them: woollen waistcoats and well knotted neckerchiefs, thick tweed jackets with worn elbows and cuffs, moleskin trousers with frayed seams tucked into the tops of their boots. The younger ones carried bundles of clothes, brown paper parcels fastened with string, slung across their shoulders or clasped to their chests, held tightly in their damp nervous hands as they started to gather pace, pulled down the hill by the sight of the city, by their eagerness to be first and by the impatience of the men and the boys pressing in from behind; still foggy from sleep, still aching from the long walk the day before, but forgetting all that as they came to their journey’s end.

From the top of the hill, where others were only now beginning that last long downward traipse, the city looked quiet and still, wrapped in a pale May morning mist, weighted with the same brooding promise that cities have always held when glimpsed from a distance like this, the same magnetic pull of hopes and opportunities. But as those first men and boys came into the city, their boots beginning to stamp and echo across the cobbled ground, windows were opened and curtains pulled back, and the city began to wake. Sleepy children peered from low upstairs windows, the hushed chatter and the rumbling of feet signalling the start of the day they’d been looking forward to, calling to each other and pulling faces at the children in the houses across the street. Landlords opened the doors and shutters of their bars, sweeping the floors and standing in their doorways with brooms in their hands to watch their customers arrive. Stallholders finished preparing their pitches around the edges of the square, keeping an eye on the small group of guards by the steps of the new town hall. And from each end of the long square, from the road leading in from the bridge to the east, from the gateway under the lodge to the west, from the road winding out along the river to the south, the army of workers appeared, hurrying on with the growing excitement of arrival, calling greetings to friends not seen for the past six months, looking around for others yet to arrive, asking after health, and families, and wives. And the crowd of people in the square grew bigger, and noisier, and fathers began to lay hands on the shoulders of their youngest sons, keeping them close, wary of letting them drift away too soon, listening to the snatches of conversation echo back and forth, looking out for the farmers and foremen to start to appear, waiting for the business of the day to begin.

Mary Friel stood with her father and brothers, watching, her youngest brother Tommy clutching her hand. You okay there Tommy? she whispered down to him. He looked up at her, nodding, a look of annoyance on his young face, and pulled his hand away.

Soon, as if at some unseen signal, deals began to be made all over the square. You looking for work son? the smartly dressed men would say, glancing down. How much you after? And the older boys, the ones who knew their price, or the ones who could say they were experienced, stronger, would get more work done, tried their luck with eight, nine, ten pounds, while the younger ones, who knew no better or could ask no more, said seven or six as they’d been told. Deals were made with a terse nod and a handing over of the brown paper packages, an instruction to meet back there in the afternoon, sometimes with a shilling or two to keep the boy busy for the day, sometimes not; sometimes the father taken for drinks to smooth over the awkwardness of the scene, sometimes not.

This was the first time Mary had been to town for the hiring fair. She’d only ever watched her father setting off with her brothers before; stood in the low doorway to wave them goodbye, her sister Cathy beside her, Tommy holding on to both their hands, their mother turning away before the boys got out of sight and saying no time to be standing around all day now. She’d had an idea of what it would be like from hearing her father those evenings he came back home alone; she and Cathy lying in bed listening while he talked in a low voice to their mother by the last few turfs of the fading fire. But she hadn’t been expecting quite so many people, or so much noise, or the way her father would stare sternly straight ahead when a gentleman approached him and said your boy looking for a job?

They left the square as soon as the price had been agreed, telling Tommy to be good, to work hard and to do what the man said, and to meet them back here at the next fair day in six months’ time. They walked through the town towards the river, Mary, her father, her two older brothers who were past the age of hiring now, out to the docks to catch the boat across to England. She listened to her brothers talking to her father as they sat waiting for the boat, talking and joking about their time as hired boys, the threshing and weeding and picking of stones, the early mornings and the endless thoughts of food. She sat slightly apart from them, looking up into the hills on the other side of the river, feeling the imprint of her young brother’s hand across the palm of her own. Other men joined them, walking over from the square, lighting up cigarettes, sitting on sacks of grain and crates of wool, talking about where they’d heard the work was that year. Following the harvests from Lancashire up to Berwick and all the way on to Fife. Waterworks round Birmingham way. Munitions in Glasgow, Manchester, Coventry, Leeds. Talking of the best ways to get there, the cheapest places to stay, the names to mention to stand a better chance of work at the end of the trip. Some of the men looked across at Mary, curiously, wondering what she might have been doing there, wondering who she was with, until their gaze was interrupted by her father’s hard glare.

They were going over the water early this year. The weather had changed sooner than usual, and the field was dug and planted, the turf cut, before fair day came. Work had been arranged for Mary, in London, and so their father had announced that they would all make the journey together. It’s a long way for a girl to go on her own, is it not? he’d said, and her mother could only agree, making up slices of cake for their journey, taking out the brown paper from its place beneath the bed.

On the boat, the four of them found a place in a quiet corner and settled themselves in, the two brothers on either side, Mary resting her head on her father’s shoulder, his heavy coat laid over them both. It smelt of damp soil and turf smoke and the cold clean air of their two days’ walking. It smelt of him and she concentrated on the smell as she drifted into an uncomfortable sleep, broken by the tip and slide of the boat, by the shouts of other men, by the hard wooden deck beneath them both.

In the morning, in Liverpool, they put her on a train down to London. They stood on the platform for a few moments to be sure she’d got a seat, watching her put her bundle up on the luggage rack, watching her smooth out her skirt as she sat down by the window. Her brother William opened the door and jumped up on to the step, leaning in to wish her a good journey, telling her to say hello to Cousin Jenny and the rest of that shower, telling her to tear up London town, laughing as he ran his hand across the top of her hair and pulled it out of its carefully pinned place. She reached out to catch him a clip round the ear but he leant away, jumping down and slamming the door shut as she said goodbye and the guard blew the whistle with his flag raised high. Her father and her other brother had already turned away.

She spoke to no one on the journey, as she’d been told, and waited under the clock at Euston station for her cousin, who came running up to meet her a half hour after the train had arrived. Sorry I’m late, she said, out of breath and a little red in the face. The bus depot was bombed last night and I had to walk all the way. You had a good crossing?

The house was in Hampstead, close enough to the Heath to see the tops of the trees from an upstairs window, its large front door reached by a broad flight of stone steps she was never allowed to use. Her room was at the top of the house, squeezed in under the rafters at the back somewhere, overlooking wash-yards and alleyways and gutters. The room was just big enough for a bed, and for a fireplace that was never lit, and for a small chest under the bed where she kept her clothes and a biscuit tin for her wages, ready to be taken home the next summer. But the size of the room was unimportant because all she ever did was sleep in there. If you were awake you were working, she said when she told someone much later what it was like. Cleaning out fireplaces, scrubbing pots and pans and boots and steps, washing and drying and ironing the clothes, lighting the fires in the family’s rooms. On her first day off she stayed in her room, counting the bruises on her knees and shins and the angry red chilblains on her fingers, sleeping, looking out of the small window and wondering where she would go if she dared to leave the house.

She lived in the attic and she worked in the basement, and part of her job was to get from one to the other without being observed. You want to be neither seen nor heard, Cousin Jenny had told her, standing at the wide stone basin scrubbing potatoes and carrots that first evening. And you want to not see or hear anything neither. Mary nodded, pushing her paper-white cap back where it kept falling down over her eyes. She learnt how to time her trips through the finely panelled rooms and corridors of the main house, going downstairs before the family had risen, waiting for their mealtimes before going back up, or for the evenings when they sat together in the drawing room. She learnt how to tip her head a little if she ever did meet someone, to say Sir or Ma’am before quickly walking away.

The thing was to make yourself invisible, she said, many years later, so that everyone could pretend you weren’t even there. You would do whatever piece of work you had to do and just slip away out of the room. Eyes down, ears closed, mouth shut. That was the thing to do, she said. So if you went in to light a fire one morning and your man was getting dressed, it wouldn’t matter because you were invisible, and he wouldn’t even know you were there. And if he asked you your name you’d tell him, and if he asked you to come closer you’d go, but you could pretend you hadn’t because really you didn’t hear or see him and he didn’t hear or see you. It wouldn’t matter at all. I was a pretty child though, she said. It wasn’t always easy to be so invisible. I tended to catch people’s eye, you know?

She would speak these words softly, eventually, but she would speak them.

Jenny took her out on their days off, showing her round London, walking through the parks if the weather was good, hiding in a picture house if the weather was bad, walking right up to the West End to look in through taped shop windows and watch out for boys. They talked about what they would do when they went back home, whether they would go back home at all, and they talked about marrying, about children, make-believing extravagant farmhouses to go with the size of the families they imagined into life. Sometimes they finished those days off in a pub in Kilburn or Camden or King’s Cross, and there were so many cousins and young aunts crowded into their corner of the bar that Mary could half close her eyes and think they were all squeezed into the lounge bar at Joe’s, with her parents’ house only a few minutes’ moonlit walk away. She saw people she hadn’t seen since she was young, and others she’d seen only at Christmas for the last few years, and they all asked for news of Fanad. She told them about Cathy’s wedding, and about the new priest, and about how her brother Tommy had gone off to work that year.

And how’s that other brother of yours, young William? a friend of Jenny’s asked once, a girl Mary remembered from church.

Oh he’s fine, she said, and the girl lowered her voice and said aye he’s more than fine, he’s very good indeed, the whole crowd of them shrieking in shocked laughter and Mary not knowing quite what they meant but laughing along all the same.

On days when it wasn’t as cold, another girl would have laid the fire the night before, sweeping out the ashes and piling up the kindling, and it didn’t take a second to slip into the room with a box of matches and set it going. But on colder days, when the embers had been left to smoulder halfway through the night, it was a much longer job. The grate had to be swept out, the ashes scooped into a metal bucket, the hearth wiped over with a damp cloth when it was done. Paper had to be screwed up into little twists and laid over with twigs and splints and pieces of kindling, and the first flares of flame had to be watched over for a few moments to see that they caught, to see that it was okay to lay on the larger lumps of log and coal and close the door softly behind her. It was too much of a job to be done silently, or invisibly; the brush would bang against the side of the grate, or the bucket, the newspaper would crackle as she screwed it up, the match-head would spit as it burst into flame. She tried very hard, but it seemed impossible not to wake whoever was sleeping in the bed behind her, not to make some small disturbance that meant she would hear a voice saying her name. A man’s voice, asking for her.

They sent her to light the fire in each of the rooms by turn, but mostly she was asked to go to the father’s room, and it was here that she found it hardest to not make a sound. After a time, she went to the housekeeper and said that if it was at all possible she would very much prefer not to go into the rooms to light the fires any more, please.

She kept it hidden the whole nine months. She wore bigger clothes. She ate as little food as she could. She stopped going out with Jenny and the others, spending long evenings and days off in her room with the chest under the bed and the small window, saying she was tired, or poorly. She learnt, too late, how to make herself invisible.