скачать книгу бесплатно

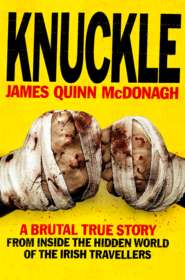

Knuckle

James Quinn McDonagh

When a simmering family feud between three clans of Irish travellers erupts after one member dies following a pub fight in London, the clans decide to go to war.Knuckle is the true story of James Quinn McDonagh – clan head and champion bare-knuckle fighter. It’s a journey from his grandfather’s horse-drawn caravan at the side of the road to the country lanes of Ireland where he stood, fists bloodied and bandaged, fighting a clan war that he never asked for.Two men, two neutral referees, a country lane. No gloves, no biting, no rests. The last man standing wins, takes home the money, and more importantly, the bragging rights.Caught in a brutal cycle of violence that has left men dead, houses burned and lives destroyed, James tells a story that opens up a hidden world – revealing why history repeats itself, and why he can never go home…‘A charismatic clan leader’- New York Times

Dedication (#ulink_0a755022-6fef-5a9a-80e5-2e5237202cad)

I would like to dedicate this book to my grandson,

James Quinn McDonagh

Contents

Cover (#ua9fbae32-72a9-5e91-ae7d-22251643f6c2)

Title Page (#u6609ce53-d09d-5a3a-9655-bded783d7bde)

Dedication

Prologue: Any Edge Is Worth Having

Chapter 1 - Born a Traveller

Chapter 2 - Boxing Gloves

Chapter 3 - England

Chapter 4 - The Beginning …

Chapter 5 - Nevins I: Ditsy Nevin

Chapter 6 - Nevins II: Chaps Patrick

Chapter 7 - Joyces I: Jody’s Joe Joyce

Chapter 8 - Joyces II: The Lurcher

Chapter 9 - The Night at the Spinning Wheel

Chapter 10 - Nevins III: Davey Nevin

Chapter 11 - The End …

Epilogue: The Traveller’s Life

Picture Section

Acknowledgments

Knuckle - The Film (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#ulink_4e941917-b01a-5792-b962-f8f1e08e0158)

ANY EDGE IS WORTH HAVING (#ulink_4e941917-b01a-5792-b962-f8f1e08e0158)

It was half-six in the morning when my eyes flicked open. Normally I would have been up half an hour already, into my clothes and out for a run. But with today being the day of the fight I wasn’t moving. All the exhausting weeks of training were now over – whatever else happened today, that was done with. An end to the jogging, weight-lifting, circuit training, the sparring that had gone on day after day for three months.

The last couple of weeks I had been winding down my training anyway, as I didn’t want to risk an injury in the days before the fight, but it was still a relief to think it was over. No more hitting bags for over an hour at a time. I could sleep a bit longer, I could eat what I wanted, and, what was more important, I could go out and enjoy myself again. I could drink what I wanted, when I wanted. No more sneaking out on a Sunday night to sink a few pints. No more setting out to jog on a Monday morning with a hangover, and turning up at the gym dripping wet – having cheated by getting a lift most of the way and pouring some water over my head just before I got there to make it look like I’d been sweating with the effort I’d put in.

Was I ready? I didn’t know. I’d done everything I could to be ready, but it was never easy. I was probably in the best shape I had ever been in. I had trained more intensively for this fight than any I had fought before. I was physically at my best and I knew that; I felt confident. I had my plans – I’d thought long and hard about how to fight, how I was going to act, and how I was going to beat him. I’d thought of what I might have to do if that didn’t work, so I had my back-up plan as well. I was prepared.

No one, though, is ever really ready for a fight like this. A man could go out and get a punch to the head that could kill him. Or he could kill someone. If I hit the man hard, like I planned to, but he slipped and fell, banged his head down on the ground – he could die. That would be with me for ever.

I lay in bed and said a few prayers. I blessed myself and prayed to God for my health, that of my wife and boys, and of my family. I said the Our Father and the Hail Mary. I prayed that the fight would go well, and that I would win. I guessed that I wasn’t the only one praying that day to win my fight but I thought, Lord, I didn’t ask for this fight, he did, so listen to me first.

You’ve got to try. Any edge is worth having.

Theresa stirred beside me and I said, ‘I’m going to go and get some milk and the papers,’ and got up and dressed. We were living in a settled house then, in a quiet area of Dundalk, in County Louth, and the shops were close by. Back home again, I started reading the papers over a cup of tea. I wasn’t trying to distract myself; I was calm, and relaxed. I knew I’d done everything I could to prepare for today and just had to wait till it was time to leave for the fight.

When a fight is called, each side will appoint their own referee from a neutral clan. It’s up to the two referees to see that fair play takes place, but before they start, the arrangements for the fight itself have to be sorted out. Both sides have to agree to the site of the fight, and the timing. Sometimes this can drag on, and then I’d know that the other side was messing with my head to get their edge over me.

I was going to be fighting Paddy Joyce – ‘the Lurcher’, he’d been nicknamed – around lunchtime. That was the idea anyway. The fight could have been delayed, though, so I needed to eat a meal that would last me through the day; I couldn’t be doing with getting hungry or tired at the wrong time. So instead of my usual breakfast I needed to get a decent meal in me now as it would most likely be the only food I’d get till the evening. I had put aside a sirloin steak in the fridge for the morning, along with some onions and a couple of eggs. That did fine.

About 9 a.m. my daddy, Jimmy Quinn, and my brothers Curly Paddy, Michael and Dave showed up. We had a cup of tea together, the four of them offering me encouragement all the time. Curly Paddy and Michael had been some of my sparring partners and they kept me focused on what I had to do later on. JJ, my son, had kept me company while I trained, and now he sat quietly with his uncles and Auld Jimmy while we talked. All the time, my phone didn’t stop ringing, people telling me they were coming down to support me, calling to wish me success, that sort of thing. I decided to make my way over to my uncle Thomas’s as I didn’t want the rest of the clan turning up on my doorstep. My neighbours had already complained about the number of cars parked around my home, some blocking their driveways, and my landlady had made it clear she didn’t much care for travellers. A hundred or so milling about outside my front door wouldn’t make me a popular man, but at my uncle Thomas’s site no one would care. Thomas didn’t really go in for the fighting himself, but he was happy to have us gather there and to see me off when it was time.

When I was ready to go I took Theresa to one side, told her I was going to win my fight, and promised to come back safely. ‘God bless you, James,’ she said, though she wasn’t happy I was fighting. She wanted me to win – ‘Up the Quinn McDonaghs!’ she’d say when I went off – but she wasn’t happy; she never had been. All the time I’d been training she’d been the one holding the family together; she always held the family together. ‘Take this and keep it with you,’ she said, and pressed into my hand a small laminated picture of a saint. Whenever I fought I’d receive these little gifts from the women in the family, my mother and aunts included. As I fought with no vest on I only had one place to slip these relics, as we called them, into, and that was my sock. By the time I left for my uncle’s site, I had five of them to fit in.

When we reached the site the clan had already started gathering. The Quinn McDonaghs all lived close by, our name marking out the triangle of land we thought of as home: from Dublin out west to Mullingar, up north to Dundalk and back south to Dublin again. There are Sligo McDonaghs, Mohan McDonaghs, Bumby McDonaghs, Galway McDonaghs, Mayo McDonaghs, even McDonaghs in England; but the Quinn McDonaghs are confined to that triangle of near enough fifty miles by fifty miles by fifty miles. At my uncle Thomas’s site, my uncles and cousins – dozens of them – were standing about waiting. One wore a white T-shirt printed with:

James

The Mightey

Quinn

Mc

Donagh

To pass the time they were playing a game of toss. I joined in, just to keep myself busy more than anything else. Heads and harps, we used to call it before the Euro came in. When I was 12 years old I’d see men out in Cara Park, in Dublin, tossing coins on a Thursday, when ‘the labour’ paid out in the morning. They’d lose all the money they’d just been given to feed their families for the rest of the week: forty, fifty pounds gone, just on the chance that the coin would keep coming up heads. They’d have three or four small kids and they’d have to go back to their wives and family with their dole gone, lost in the toss pit. They’d struggle on for the following week, and then go straight out to gamble again.

If the coin turned up harps, then the other guy would step in. I’ve seen men walk away from the toss pit with up to IR£800 in their hands. I’ve lost six hundred in an afternoon myself, all on the toss of a coin. I had a run of luck that day that didn’t help. It was at my brother Michael’s wedding, and I had to borrow two hundred from someone else just to have some spending money for the rest of the evening. I felt bad about that but it helped me when it came to a fight – I knew what it was like to lose money, and didn’t want to lose the purse. I knew how bad I felt after losing a few hundred, so how bad would it be if I was to lose ten, twenty, or even thirty grand?

I won a little bit and lost a little bit of money that day at the wedding. I didn’t take that as any kind of omen at all – it was just something that relaxed me. Playing toss meant I didn’t go into fight mode too early. Trying to get myself up too soon would just make me tense and tired. It was only when I was on my way to the fight that I’d get into character. That may sound funny, but it’s true. I’m not a violent man; to take up the challenge of these fights was something I did for our family name. The character the rival clans – the Joyces, the Nevins – thought I was, some kind of tough guy – they’d created that. I hadn’t. I had no interest in fighting other than defending the name of the Quinn McDonaghs, and winning that purse.

Soon there were well over a hundred people around me. The Quinn McDonaghs were out in force because I was fighting for our name and they’d come to support me. My uncle Chappy – one of the nicest people I know – came over, and he was riled up by the fight. He gripped my arm with his hand. ‘James, you listen to me. You see them people’ – he waved south, in the direction of where the fight would take place, and I nodded as he continued – ‘all them Joyces and all them Nevins. They’ve never beaten you. Now you’ve done your training, you know what you’re doing. Come back here and do not lose. I’m telling you straight: do not lose this, you make sure that you beat him, and if you beat him you’ve them all beat.’ That’s how much it meant to everyone, that even someone like Chappy could get worked up by the fight. If I beat the Lurcher, then, as Chappy told me, ‘That’s them people gone for ever.’ Big Joe Joyce had said the same to me when he called to arrange the day and time of the fight. ‘You’re fighting the best man of the Joyces. If you beat him, there’ll be no more. We’ll leave you alone,’ he’d said, although I didn’t think for a moment they would. The only hope I had of making sure they didn’t send for me again was if I really hurt the Lurcher. That might be the only way of stopping further fights.

I knew, too, what it would mean if I lost this fight. Then every Joyce and Nevin would be queuing up to take a shot at the Quinn McDonaghs. The other clans had pushed me up onto this place where I was their target, so if one of them managed to knock me down, then in their eyes they would have knocked down the whole Quinn McDonagh clan. To them that’s what this fight meant.

A reporter had shown up who’d heard about the fight and wanted to come and talk to me and then put some pictures of the fight in the paper. I told him why we were fighting. ‘There’s bad blood between the two families, and it’s been going on for years.’ My dad added, ‘Fifty years.’ The reporter also asked about the purse and if the fight was really about that. I smiled but explained that all that meant was ‘a few quid for Christmas too’.

What the reporter didn’t understand was that if I did win, I wasn’t winning £20,000. When we got the money at the end of the fight we’d first give each referee £500. And then I hadn’t put up £10,000 on my own; my family and I had gone to uncles and cousins and everyone would put in a little, a few hundred or maybe more. That way, if I lost, no one lost a lot of money, and if I won, then everyone would get a little share. Winning the fight wouldn’t make me a rich man, but I didn’t tell the reporter that.

The rest of my cousins and uncles then came over to offer me a few words of praise, encouragement and advice. Back-seat drivers, I call them; people with great beer guts who lived in the pub and had never trained in their lives telling me what to do, how to put myself about – and I was the one who’d put in about fourteen weeks’ training for this. So I smiled and thanked them but I didn’t really listen. Once I was standing there in front of Paddy the Lurcher, I’d be the only one who was there to fight him.

I didn’t know what sort of fighter he was going to be, because I’d never seen him fight, although he would have seen the videos of my fights. I didn’t even know what he looked like now, as I hadn’t seen him since the London days nearly fourteen years ago. I’d had some feedback from someone who’d seen him train, and the report said he’d bust the punch-bag hanging in Big Joe’s shed during training.

Hang on a second; how can you bust a punch-bag? Muhammad Ali didn’t bust a punch-bag. What bag was the Lurcher boxing now? A paper bag? A plastic bag? The man is an animal, I was told. He’s breaking the bags off the wall. You’re better off calling the fight off. Was this a game plan of the Joyces? I wondered. There was an awful lot of money riding on this fight and if I refused to fight him I’d lose it all. Was I being fed some line here? Was this meant to get back to me to upset me in my training?

That wasn’t for me to worry about; if anything, it inspired me to train harder. I kept a clear head; I’d fought before, and each time the fight had been out in the open air. This man hadn’t, and his record was one of bullying people, and all the tales I’d heard – of him beating this man, beating that – didn’t worry me because I had no way of knowing if they were people he knew he could beat before a fight, if they were no match for him. There were no tapes to watch, so they could have been what we call ‘fair fights’, or they might not have been. I wasn’t going to give him a chance, and I figured that if I kept my concentration, stuck to my plans, changed from one plan to another if necessary when I was fighting, I’d be OK. I knew I was fit enough.

When I was a kid growing up, I’d trained to be a boxer, I’d learned the basic moves. Left hand slightly out, right hand just above the chin, left leg out, back leg secure. From the age of 16, though, I had no training and the moves that I’d learned before I’d now refined into my own style. Come out, step forward, hit, step off. I’d sparred with people the Lurcher’s size, as far as I could tell, and I’d prepared myself to move quickly so he wouldn’t be able use his height and weight against me.

While I was fighting I’d keep my left arm out in front of me, feeling my way, my fist close to whoever I was fighting so my opponent couldn’t see me clearly enough. If he tried to slap my left arm away, the next minute my right would be sitting in his face. ‘The fishing pole’, the Joyces and the Nevins called it. They didn’t like it one bit. It disturbed my opponents, and broke their concentration. All my trainers when I was in boxing clubs as a young teenager told me not to use my left arm like that, but it was a tactic that always worked for me. I wasn’t going to change it, because it kept me at arm’s length from danger, I’d tell everyone. It was a shield to protect me. I could use it like a poker, jabbing at someone’s eye.

Ned Stokes, my referee, and two of his sons drove into the site about half-eleven. We shook hands. ‘I wish you luck, James. I hope it goes well for you,’ he said. I took a phone call off Paddy’s referee, Patrick McGinley, and relayed what he’d said to me to Ned: that we were meeting him and the Lurcher in a place down in Drogheda, about twenty miles to the south. To the cheers and applause of the waiting crowd, we got into Ned’s car, his sons in the one behind, and drove away.

From Dundalk it was just under half an hour’s drive on the M1. As he drove Ned Stokes talked about nothing in particular, a pleasant chat designed to take my mind off what the next couple of hours would bring. Once we came off the motorway and into Drogheda I had to find somewhere to wind myself up and get myself into fight mode. My phone would still have been ringing if I hadn’t switched it off. Having a moment to yourself is a rare thing for any traveller, and as for myself I found that there were some days when my house felt like Piccadilly Circus. I needed some time alone now. ‘Pull into this McDonald’s, will you, Ned,’ I said. ‘I need to use the toilet.’

Above the washbasins in the toilet was a mirror. I stared into it and spoke to myself. ‘This is your day, pal. Are you going to do it?’ I hadn’t planned to talk to myself, it just came to me at that moment. I thought of what those lads, my supporters, had been telling me to do; good things, advising me, encouraging me, telling me that the Lurcher was no good and that he couldn’t fight, and trying to get me worked up. But they weren’t here now, I told myself. I was the one who’d have to go out and fight for them all, for the Quinn McDonagh name. The weight of that lay heavily on my shoulders and on some days that pressure told on me, but today wasn’t one of those days. I was strong and fit and determined, and I wanted to go and fight Paddy. I wanted to hit him, to hurt him. To do that now meant I had to hate him. I remembered seeing him in London years ago, watching him bully people, and I focused on that as it helped me create that hatred. This was part of what I had to do – slipping into the role of James the fighter, James Quinn, son of Jimmy Quinn, a role I only have because it’s been forced on me.

It wasn’t hard to find reasons to hate Paddy Lurch; for the past few months I’d neglected so much of my life as I concentrated on this fight, what with the training and the dieting. If I didn’t work, I didn’t earn any money. I’d not spent time with my family. Instead I’d been in the gym, in that boxing ring, day after day for weeks on end. I’d not been to the pub to enjoy myself. I’d had to stop almost everything I was doing so that I could be ready for today. Paddy was the cause of that and the more I thought about what I’d had to stop and what I’d missed out on, the angrier I became. I wanted him to feel the pain that I’d felt for those endless weeks, the pain I’d felt in my muscles and joints as I trained, the aches I’d had those early mornings as I pulled myself out of bed to go jogging. I’d used every moment of the last few weeks to focus my anger on him. No spare time, no drink. No work, no money. All because of the Lurcher.

I needed to get angry because I had to stand in front of Paddy and try to hurt him. I had to be ready to cut his face, to cause him to get stitches under his eyes. Ready to knock him down, ready to give him concussion. Ready to disfigure him with a blow to the nose or the cheek. Ready to hit him hard enough on the head to give him a haemorrhage. Did I care? No. I hadn’t asked for this fight. He had. He was the one who’d made us do this, not me, and I used that to get myself more angry, to really start to hate the man and all those in his clan who’d put him up to fight me. We were here because of him, we were both risking our health and maybe even our lives because of him, and that made me angrier still.

A travelling man’s life is shorter than a settled man’s; the average life expectancy for a travelling man is sixty-seven years. That’s twenty years less than for a settled man. We Quinn McDonaghs have a high rate of heart disease and cancer; there’s heart problems in many of my uncles as well as my mother and father. So why was I adding to the problem by going out to maybe end this man’s life or maybe – if I took a blow in a bad way – my own? The anger boiled hotter.

Good. It was working. I looked into the mirror and repeated, ‘Today, James, you can do it.’

I had been provoked into this fight, and I had no choice but to win it. I had to succeed because if I didn’t hit him, hurt him, knock him down and keep him there, he’d do exactly that to me. I didn’t want to do this. I’m not someone who seeks fights; I’ve never looked for a scuffle in a pub on a Saturday night. I wasn’t proud that I was going to be doing this, I wasn’t happy; but this is what the fights were about. If I was going to win it was because I was ready to do everything I had to. I hated the Lurcher with a vengeance. I had to, otherwise I wasn’t going to win my fight. If I hadn’t hated him, I’d have felt sorry for him, I’d have felt pity – but I didn’t. I didn’t feel sorrow or pity, or compassion. I felt hatred. I wanted to get stuck in, hurt and maim that person. Hurting him badly would make another man think twice before challenging me, and that meant no more fights. So the hatred drove my aggression, and I needed that. That person has upset my whole life, I was thinking, and he’s getting me a name that I don’t like.

The name. It was all about the name.

I left the toilet and got back into the front car. While I’d been inside, Ned had taken the call telling us which location to go to, so with one of his sons in the car behind we set off again. The location was only five minutes away. I held my hands out to the lads in the back and they went to work, running bandages over my hands, thumbs and wrists.

As soon as we arrived at the site I wasn’t happy. I climbed out of the car and looked around but I knew we weren’t going to stay. There was nothing wrong with the place itself; it was the number of people already there to watch the fight I wasn’t pleased to see. I had deliberately left my family behind, and nobody had come with me except the referee, who was independent anyway, and his two sons; a cameraman, to tape the fight so that it could be seen by everyone back in Dundalk later on; and my second, who I needed to tie up my bandages. I’d expected Paddy Lurch to have the same around him too. Instead there was a gang of about fifteen or so there, hanging about waiting for the fight to start. I recognised some faces right away, people I’d fought in the past, Chaps Patrick, Ditsy Nevin, and a dozen or so other Nevins hanging around with them both. There is no doubt whose side they’d all be on when the fight started and I didn’t think that made it fair at all. No wonder Paddy Lurch had suggested this place for the fight. He might as well have said we’d fight at his house.

I got back into the car. ‘I ain’t fighting here,’ I said to Ned. He said, ‘Yes, the agreement we made was none of them people were coming to the fight, there was no other spectators.’ Patrick McGinley had come over to talk to Ned and had his head in through the driver’s window and he heard what Ned was saying. ‘That’s all right, James,’ Patrick said. ‘If you don’t want to fight here, then we won’t fight here.’

The Nevins didn’t like it when they saw me get back into the car. Chaps Patrick, though, came up and said, ‘Would you mind, James, if me and the lad come to the fight?’ He had his young son with him, a boy of about 7 or 8. Why he wanted to bring a kid to watch two men knock lumps out of each other I don’t know. ‘That’s all right, I don’t mind if you two come but’ – I pointed at the Nevins lined up alongside Ditsy – ‘I don’t want those others there.’

This set Ditsy off. Ned was turning the car round and Ditsy started yelling at me, ‘Get out and fucking fight, you cowardly fuck, yer. Get out and fight yer man here.’ I turned to Ned and said, ‘Now you see why I don’t want them there.’ Ned said, ‘James, I understand 100 per cent,’ and we drove away, Ditsy still gesturing and yelling at the car as we left him behind.

Ned drove to the end of a quiet back lane outside Drogheda, and the car with his boys and one with Chaps Patrick followed on. The bandages on my fists were tightened and checked by my second and I pulled off my sweatshirt and started to walk back up the lane to where we were going to fight. It was a grey November day, probably cold, but I didn’t notice, as I’d started to block out what was going on around me. I was narrowing my focus on the things that mattered now, because concentration would win me the fight. One moment when I was not looking at my opponent, where his fists were, what his feet were doing, and – most importantly – where his eyes were looking to, and it could all be over. I’d learned that; fighting someone, their eyes would look where they wanted to go to next, where they wanted to aim for, where they were planning to hit me. It never failed, this; I knew I had a moment to strike back before they could hit me if their eyes led the way. I never took my gaze off my opponent’s face; if I had to hit him on his chin, I knew it was somewhere below his eyes and nose. I didn’t need to look to know that.

At this point I still hadn’t seen the Lurch. Ahead I could see a couple of cars pull up and stop, and a guy got out of one of them. I knew that Paddy was a red-haired feller, big, and I believed a little slow in his movements; but this man was rolling his shoulders, stretching out his neck, shaping himself in a way that I hadn’t expected – someone who knew what he was about. I asked Ned, ‘Is that Paddy Lurch? Is that the Lurch, Ned?’ ‘No,’ he said, looking over at the man. ‘That’s young Maguire.’ I didn’t even know what the Lurch looked like and I was about to fight him.

Then he stepped out of McGinley’s car and there was no doubt this was him. He was as big as me, in tracksuit bottoms and a red vest, and bandages on his hands. I nodded over and he nodded back at me, the courtesy of a head wave but no more. The two referees came over to check my bandages – to make sure I’d nothing tied under the bandages that would make a punch more painful – and were happy enough with them. Then they called the Lurcher, still wearing his red vest, over and we listened while Ned ran over the rules. ‘The agreement is, if a man is down he gets up. Arms round each other is a foul, but when you’re in tight, no man can stop it. No fouling, no dirty punches. If you break, you break clean.’

The Lurch pulled off his vest and said, ‘There’s one thing I want to say, James: your brother Paddy’s the cause of all of this.’

‘Lurch, there’s no need for this,’ I told him. ‘You shouldn’t have sent for me, you should have sent for Paddy.’

‘I don’t send for murderers,’ he replied. The fight hadn’t started and he was goading me. I started to answer back but Ned broke in.

‘Excuse me, boys,’ he said, talking over us both. ‘No bad language, boys.’

‘No biting, no holding, no head-butting,’ added Patrick McGinley. ‘Now shake hands.’

‘No,’ Paddy said immediately, and I retorted, ‘No, no shaking hands.’

The referees stepped back.

I moved forward, hopping from foot to foot, my left arm in front of me, right curled back, ready to land the first blow.

Chapter 1 (#ulink_032faf90-80e5-5e4c-b4b3-00c497f9fe99)

BORN A TRAVELLER (#ulink_032faf90-80e5-5e4c-b4b3-00c497f9fe99)

Growing up, this fighting thing never came into my mind. I never thought either about being a policeman, being a solicitor, being a fireman – none of those. I was a traveller, and they weren’t things that I would even have thought of doing with my life. I would do what travellers did. That was the only path open to me.

I was born in County Westmeath in 1967. For my first few years I lived with my grandfather, Auld Daddy, my mother, older brother Curly Paddy and older sister Bridgie, all of us in an old-fashioned barrel-top wagon, the kind pulled by horses. The main bed was inside at the back of the wagon, and there was a little stove to keep us warm and a box for the bread. To keep me safe when I was a baby while he slept, my grandfather would loop a bit of rope around my middle and tie the other end around his ankle. If I tried to crawl off, the rope would tug and he’d wake up.

Auld Daddy had two horses, one to tow the wagon, the other to breed from, so we could sell the foals. We wouldn’t sleep in the wagon, not us kids anyway; we would sleep under the wagon, or at the side of the road in a ‘tent’ made of branches from the hedges. The dogs would sleep anywhere they could; they weren’t pets, they were working dogs. My mother would cook on an open fire, and she’d wash our clothes with water from the river. In the summertime, when it was warm, we’d sit by the fire and we’d sing songs and be told stories of Irish myths from many years ago. The story-teller, usually Auld Daddy, would tell us ghost stories about the banshees, to frighten us off to bed.

We’d sleep in the tent, in straw that the farmer would give us when we arrived. My mother would shake it all up, spread the blanket out, and I’d climb in. I’d wrap the blanket round me and as I sank into the straw it would just fall around me. It was like a big quilt, nice and warm on a cold night.

To an outsider it might have looked romantic, a simple life like that, but it wasn’t, it was very hard. In the summer it might have looked the same as a nice camping trip but if you go camping you only go for a few days and then come home, whereas we were living like that all year round. In the winter it was a very harsh life. Rural Ireland was poor then and travellers were the poorest of the poor. In those days travellers lived off the land, making things like clothes pegs that could be sold door to door and at the markets, and from the seasonal work farmers would give them, such as picking spuds in the autumn. We had to beg for clothes from the local families, the settled people. We had no other way of getting basics of that sort.

I was born when my father was in England. He’d travelled over there for work, got mixed up in some trouble, and ended up in prison. If years back a man was in jail or away working, his wife would go back to her family, so my mother went back to her father, and he looked after her. The first time my father saw me I was 2½ years old.

My father was Jimmy Quinn, son of Mikey Quinn. Those names go through the generations: I’m James Quinn, it’s my son’s name, and my grandson’s name, and before Mikey came Martin, and before him was Mickey McDonagh. Mickey married a woman called Judy Caffrey and together they had five sons and five daughters. Mickey’s mother was one of three sisters known as ‘the Long Tails’ for the dresses they wore. All these names I grew up with around the fire; there was nothing written down about our family and stories like those, about these memorable dresses, only survive because they were passed on. Travellers’ lives were mostly just hidden away in history. Mickey’s son Martin was my great-grandfather and he went on to have five sons as well. His wife was a Joyce, Winnie Joyce, and her brother Patsy married Martin’s sister, linking the Joyces and the Quinn McDonaghs together right through to this day. One of my grandfather’s brothers also had several children, among them Padnin Quinn, Davey ‘Minor Charge’ Quinn, and Cowboy Quinn – and my mother. The Nevins also married into the family back in those generations – so we’re all related, even if we do feud with each other.

There is a Quinn connection going back a long way, even though we’re the Quinn McDonaghs. I never knew why we always made such a thing of the ‘Quinn’ part and didn’t really pay much attention to the ‘McDonagh’ bit, but I was told two versions of the story when I was growing up. Both involve Mickey McDonagh coming back into a camp, chased by the police. One version says it was because he was running from them after stealing something, the other says it was because he didn’t want to be conscripted into the British Army for the First World War. Either way, when the police came into the camp and discovered there were five Michael McDonaghs on the site, he was asked, ‘Are you Mickey McDonagh?’, to which he said ‘Me? No, I’m Michael Quinn,’ taking his mother’s maiden name (Abigail Quinn was another of the Long Tail sisters), and from then on the Quinn McDonagh name was used.

My uncle Michael was known as Chappy; my uncle Martin was known as Buck; my uncle Kieran was known as Johnny Boy. Most of the time I never knew why some people had the nicknames they had, but even as children we all knew why my father’s cousin Bullstail Collins was called Bullstail and not Martin Collins. One day he was standing by a farmer’s gate and the bull in the field was scratching his arse against the fence. Martin Collins decided to tie his tail onto the gate and hit him with the stick. The bull went and the tail stayed – and that’s why he’s always known as Bullstail.

When I was growing up my dad travelled with his family round the area of Ireland we lived in, and when I was a little boy I loved to hear their stories. My father grew up with seven brothers and five sisters, and with all those mouths to feed everyone had to contribute. (Large families were a feature of traveller life, and my sister married a man with twenty-two brothers and sisters. My own wife Theresa has seventeen uncles and aunts.) In the 1940s and 1950s life on the roads was very, very rough, and my father used to say if it hadn’t been for the farmers the travelling people of Ireland wouldn’t have survived. The farmers gave them work and – when they were able to – donations of food and clothing as well. My father’s family lived off what they could earn and what they were given.

One of the stories we all heard when growing up was about the Christmastime when my father went out, with two of his older sisters, to see if they could get him some shoes. He was only 3½ years old. ‘I was walking out with nothing on my bare feet, in the snow,’ he’d say, and we’d all try to imagine how cold that must have been. His childhood had gone quickly and by the age of 11 he was in the fields with his family picking spuds from August through to the winter. ‘The first day’s wages I ever got,’ he’d tell us as we sat by the crackling fire, ‘was a half a crown for walking with a plough over at Carnaross, County Meath, and that’s back in the 1950s.’ He would describe his battle with the heavy plough and the thick, heavy soil. With his wages he bought a beer but he’d always make sure we knew that he’d ‘given my mother a shilling’.

The family would eat what they could find, and share what they had with whoever was around them. My father loved to tell us about the time he and his brother Buck went out and gathered some spuds and carrots from the field, which they gave to their mother to put in her large pot (as children we all feared the witches’ pot, as we called it). Then they went out and caught a couple of rabbits and a hare, and then managed to catch a duck in a local pond, and – and this was the risky thing – a pheasant too. All of these went into the pot with whatever else my granny could find and their family, and the five families around them, feasted on that for dinner. As children we couldn’t understand how anyone could eat all of those things at one time, but I suppose if you’re very hungry, as they all were, you wouldn’t care. Certainly my father remembered the entire pot being emptied that night.

Just as we were told how good and kind the farmers and their families were in those days, we’d also be reminded of what could happen if we weren’t respectful of them in return. When my father was young, his uncle was out in Galway somewhere and had a confrontation with the farmer beside whose land he was staying. The farmer accused him of raiding the hedges for timber to keep his fire going and my father’s uncle denied this, saying he’d scavenged the timber from where it had fallen on the side of the road. He stood up to talk to the farmer, and the farmer claimed he saw him pulling out an iron bar and thought he was going to hit him, so he produced a gun and blew my dad’s uncle’s head off. Killed him like that, over his own fire by the side of the road. The farmer was taken to court about it but he claimed he’d shot him in self-defence and no one disagreed with him. So we were told always to mind what the farmer told us and not to think we could do as we liked. That story was often repeated to us to remind us that the law didn’t always look too favourably on travellers and so we should be careful not to come into contact with the police if we could help it.

There were times when we relied on the Guards – what travellers called the Garda, the Irish Police. In my father’s young days no traveller had a telephone – just as we didn’t when I was young, of course – so if there was a death, or another reason to need to meet up with another family, then it was the Guards who would pass on a message. A traveller would go into the local Garda office and ask them to pass on a message to the Quinn McDonaghs up in Meath. The Garda would then ring some local stations and ask if we were known to be in the area, and if so, could an officer go out and find the family and carry a message to them? Usually the Guards would know who was in their area and roughly where they were, so it wouldn’t take them long to find whoever they were looking for.