Полная версия:

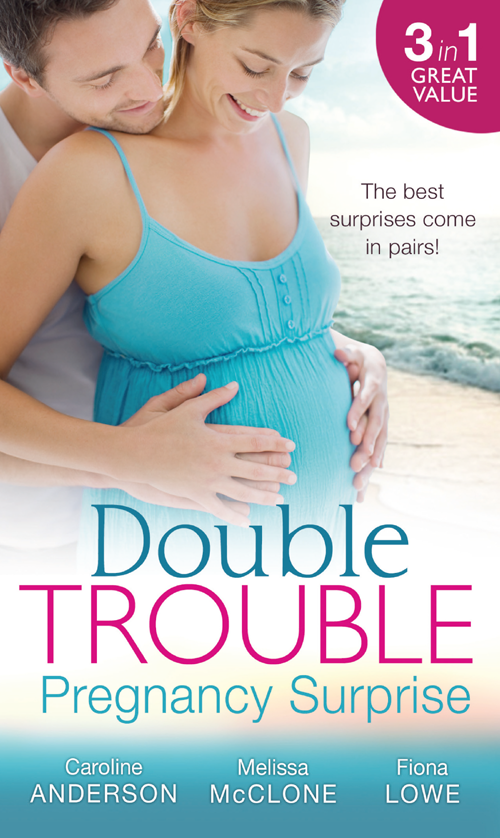

Double Trouble: Pregnancy Surprise: Two Little Miracles / Expecting Royal Twins! / Miracle: Twin Babies

Double Trouble: Pregnancy Surprise

Two Little Miracles

Caroline Anderson

Expecting Royal Twins!

Melissa McClone

Miracle: Twin Babies

Fiona Lowe

www.millsandboon.co.uk

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Two Little Miracles

About the Author

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

EPILOGUE

Expecting Royal Twins!

About the Author

Dedication

Acknowledgements

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

EPILOGUE

Miracle: Twin Babies

About the Author

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

EPILOGUE

Copyright

CAROLINE ANDERSON has the mind of a butterfly. She’s been a nurse, a secretary, a teacher, run her own soft furnishing business and now she’s settled on writing. She says, ‘I was looking for that elusive something. I finally realised it was variety and now I have it in abundance. Every book brings new horizons and new friends and in between books I have learned to be a juggler. My teacher husband John and I have two beautiful and talented daughters, Sarah and Hannah, umpteen pets and several acres of Suffolk that nature tries to reclaim every time we turn our backs!’ Caroline also writes for the Mills & Boon® Medical Romance™ series.

PROLOGUE

‘I’M NOT going with you.’

Her voice was unexpectedly loud in the quiet bedroom, and Max straightened up and stared at her.

‘What? What do you mean, you’re not coming with me? You’ve been working on this for weeks—what the hell can you possibly have found that needs doing before you can leave? And how long are you talking about? Tomorrow? Wednesday? I need you there now, Jules, we’ve got a lot to do.’

Julia shook her head. ‘No. I mean, I’m not coming. Not going to Japan. Not today, not next week—not ever. Or anywhere else.’

She couldn’t go.

Couldn’t pack up her things and head off into the sunset—well, sunrise, to be tediously accurate, as they were flying to Japan.

Correction: Max was flying to Japan. She wasn’t. She wasn’t going anywhere. Not again, not for the umpteenth time in their hectic, tempestuous, whirlwind life together. Been there, done that, et cetera. And she just couldn’t do it any more.

He dropped the carefully folded shirt into his case and turned towards her, his expression incredulous. ‘Are you serious? Have you gone crazy?’

‘No. I’ve never been more serious about anything. I’m sick of it,’ she told him quietly. ‘I don’t want to do it any more. I’m sick of you saying jump, and all I do is say, “How high?”’

‘I never tell you to jump!’

‘No. No, you’re right. You tell me you need to jump, and I ask how high, and then I make it happen for you—in any language, in any country, wherever you’ve decided the next challenge lies.’

‘You’re my PA—that’s your job!’

‘No, Max. I’m your wife, and I’m sick of being treated like any other employee. And I’m not going to let you do it to me any more.’

He stared at her for another endless moment, then rammed his hands through his hair and glanced at his watch before reaching for another shirt. ‘You’ve picked a hell of a time for a marital,’ he growled, and, not for the first time, she wanted to scream.

‘It’s not a marital,’ she said as calmly as she could manage. ‘It’s a fact. I’m not coming—and I don’t know if I’ll be here when you get back. I can’t do it any more—any of it—and I need time to work out what I do want.’

His fists balled in the shirt, crushing it to oblivion, but she didn’t care. It wasn’t as if she’d been the one who’d ironed it. The laundry service took care of that. She didn’t have time. She was too busy making sure the cogs were all set in motion in the correct sequence.

‘Hell, Jules, your timing sucks.’

He threw the shirt into the case and stalked to the window, ramming his hand against the glass and staring out over the London skyline, his tall, muscled frame vibrating with tension. ‘You know what this means to me—how important this deal is. Why today?’

‘I don’t know,’ she said honestly. ‘I just—I’ve hit a brick wall. I’m so sick of not having a life.’

‘We have a life!’ he roared, twisting away from the window and striding across to tower over her, his fists opening and closing in frustration. ‘We have a damn good life.’

‘No, we go to work.’

‘And we’re stunningly successful!’

‘Business-wise, I agree—but it’s not a life.’ She met his furious eyes head-on, refusing to let him intimidate her. She was used to Max in a temper, and he’d never once frightened her. ‘Our home life isn’t a success, because we don’t have a home life, Max. We didn’t see your family over Christmas, we’ve worked over New Year—for God’s sake, we watched the fireworks out of the office window! And did you know today’s the last day for taking down the decorations? We didn’t even have any, Max. We didn’t do Christmas. It just happened all around us while we carried on. And I want more than that. I want—I don’t know—a house, a garden, time to potter amongst the plants, to stick my fingers in the soil and smell the roses.’ Her voice softened. ‘We never stop and smell the roses, Max. Never.’

He frowned, let his breath out on a harsh sigh, and stared at his watch. His voice when he spoke was gruff.

‘We have to go. We’re going to miss our flight. Take some time out, if that’s what you need, but come with me, Jules. Get a massage or something, go and see a Zen garden, but for God’s sake stop this nonsense—’

‘Nonsense?’ Her voice was cracking, and she firmed it, but she couldn’t get rid of the little shake in it. ‘I don’t believe you, Max. You haven’t heard a damn thing I’ve said. I don’t want to go to a Zen garden. I don’t want a massage. I’m not coming. I need time—time to think, time to work out what I want from life—and I can’t do that with you pacing around the hotel bedroom at four o’clock in the morning and infecting me with your relentless enthusiasm and hunger for power. I just can’t do it, and I won’t.’

He dashed his hand through his hair again, rumpling the dark strands and leaving them on end, and then threw his washbag in on top of the crumpled shirt, tossed in the shoes that were lying on the bed beside the case and slammed it shut.

‘You’re crazy. I don’t know what’s got into you—PMT or something. And anyway, you can’t just walk out, you’ve got a contract.’

‘A con—?’ She laughed, a strange, high-pitched sound that fractured in the middle. ‘So sue me,’ she said bitterly, and, turning away, she walked out of their bedroom and into the huge open-plan living space with its spectacular view of the river before she did something she’d regret.

It was still dark, the lights twinkling on the water, and she stared at them until they blurred. Then she shut her eyes.

She heard the zip on his case as he closed it, the trundle of the wheels, the sharp click of his leather soles against the beautiful wooden floor.

‘I’m going now. Are you coming?’

‘No.’

‘Are you sure? Because, if you don’t, that’s it. Don’t expect me to run around after you begging.’

She nearly laughed at the thought, but her heart was too busy breaking. ‘I don’t.’

‘Good. So long as we understand one another. Where’s my passport?’

‘On the table, with the tickets,’ she said without turning round, and waited, her breath held.

Waited for what—some slight concession? An apology? No, never that. I love you? But she couldn’t remember when he’d last said those words, and he didn’t say them now. She heard his footsteps, the wheels of his case on the floor, the rattle of his keys, the rustle of paper as he picked up the flight details, his passport and tickets, then the click of the latch.

‘Last call.’

‘I’m not coming.’

‘Fine. Suit yourself. You know where to find me when you change your mind.’ Then there was a pause, and again she waited, but after an age he gave a harsh sigh and the door clicked shut.

Still she waited, till she heard the ping of the lift, the soft hiss of the door closing, the quiet hum as it sank down towards the ground floor.

Then she sat down abruptly on the edge of the sofa and jerked in a breath.

He’d gone. He’d gone, and he hadn’t said a word to change her mind, not one reason why she should stay. Except that she’d be breaking her contract.

Her contract, of all things! All she wanted was some time to think about their lives, and, because she wouldn’t go with him, he was throwing away their marriage and talking about a blasted contract!

‘Damn you, Max!’ she yelled, but her voice cracked and she started to cry, great, racking sobs that tore through her and brought bile to her throat.

She ran to the bathroom and was horribly, violently sick, then slumped trembling to the floor, her back propped against the wall, her legs huddled under her on the hard marble.

‘I love you, Max,’ she whispered. ‘Why couldn’t you listen to me? Why couldn’t you give us a chance?’

Would she have gone with him if he’d stopped, changed his flight and told her he loved her—taken her in his arms and hugged her and said he was sorry?

No. And, anyway, that wasn’t Max’s style.

She could easily have cried again, but she wouldn’t give him the satisfaction, so she pulled herself together, washed her face, cleaned her teeth and repaired her make-up. Then she went back out to the living room and picked up the phone.

‘Jane?’

‘Julia, hi, darling! How are you?’

‘Awful. I’ve just left Max.’

‘What! Where?’

‘No—I’ve left him. Well, he’s left me, really…’

There was a shocked silence, then Jane said something very rude under her breath. ‘OK, where are you?’

‘At the apartment. Janey, I don’t know what to do—’

‘Where’s Max now?’

‘On his way to Japan. I was supposed to be going, but I just couldn’t.’

‘Right. Stay there. I’m coming. Pack a case. You’re coming to stay with me.’

‘I’m packed,’ she said.

‘Not jeans and jumpers and boots, I’ll bet. You’ve got an hour and a half. Sort yourself out and I’ll be there. And find something warm; it’s freezing up here.’

The phone went dead, and she went back into the bedroom and stared at her case lying there on the bed. She didn’t even own any jeans these days. Or the sort of boots Jane was talking about.

Or did she?

She rummaged in the back of a wardrobe and found her old jeans, and a pair of walking boots so old she’d forgotten she still had them, and, pitching the sharp suits and the four-inch heels out of the case, she packed the jeans and boots, flung in her favourite jumpers and shut the lid.

Their wedding photo was on the dressing table, and she stared at it, remembering that even then they hadn’t taken time for a honeymoon. Just a brief civil ceremony, and then their wedding night, when he’d pulled out all the stops and made love to her until neither of them could move.

She’d fallen asleep in his arms, as usual, but unusually she’d woken in them, too, because for once he hadn’t left the bed to start working on his laptop, driven by a restless energy that never seemed to wane.

How long ago it seemed.

She swallowed and turned away from the photo, dragged her case to the door and looked round. She didn’t want anything else—any reminders of him, of their home, of their life.

She took her passport, though, not because she wanted to go anywhere but just because she didn’t want Max to have it. It was a symbol of freedom, in some strange way, and besides she might need it for all sorts of things.

She couldn’t imagine what, but it didn’t matter. She tucked it into her handbag and put it with her case by the door, then she emptied the fridge into the bin and put it all down the rubbish chute and sat down to wait. But her mind kept churning, and so she turned on the television to distract her.

Not a good idea. Apparently, according to the reporter, today—the first Monday after New Year—was known as ‘Divorce Monday’, the day when, things having come to a head over Christmas and the New Year, thousands of women would contact a lawyer and start divorce proceedings.

Including her?

Two hours later she was sitting at Jane’s kitchen table in Suffolk. She’d been fetched, tutted and clucked over, and driven straight here, and now Jane was making coffee.

And the smell was revolting.

‘Sorry—I can’t.’

And she ran for the loo and threw up again. When she straightened up, Jane was standing behind her, staring at her thoughtfully in the mirror. ‘Are you OK?’

‘I’ll live. It’s just emotion. I love him, Janey, and I’ve blown it, and he’s gone, and I just hate it.’

Jane humphed, opened the cabinet above the basin and handed her a long box. ‘Here.’

She stared at it and gave a slightly hysterical little laugh. ‘A pregnancy test? Don’t be crazy. You know I can’t have children. I’ve got all that scarring from my burst appendix. I’ve had tests; there’s no way. I can’t conceive—’

‘No such word as can’t—I’m living proof. Just humour me.’

She walked out and shut the door, and with a shrug Julia read the instructions. Pointless. Stupid. She couldn’t be pregnant.

‘What on earth am I going to do?’

‘Do you want to stay with him?’

She didn’t even have to think about it. Even as shocked and stunned as she was by the result, she knew the answer, and she shook her head. ‘No. Max has always been really emphatic about how he didn’t want children, and anyway, he’d have to change beyond recognition before I’d inflict him on a child. You know he told me I couldn’t leave because I had a contract?’

Jane tsked softly. ‘Maybe he was clutching at straws.’

‘Max? Don’t be ridiculous. He doesn’t clutch at anything. Anyway, it’s probably not an option. He told me, if I didn’t go with him, that was it. But I have to live somewhere; I can’t stay with you and Pete, especially as you’re pregnant again, too. I think one baby’s probably enough.’ She gave a shaky laugh. ‘I just can’t believe I’m pregnant, after all these years.’

Jane laughed a little self-consciously. ‘Well, it happens to the best of us. You’re lucky I had the spare test. I nearly did another one because I didn’t believe it the first time, but we’ve just about come to terms with it—and I’m even getting excited now about having another one, and the kids are thrilled. So,’ she said, getting back to the point, ‘Where do you want to live? Town or country?’

Julia tried to smile. ‘Country?’ she said tentatively. ‘I really don’t want to go back to London, and I know it’s silly, and I’ve probably got incredibly brown thumbs, but I really want a garden.’

‘A garden?’ Jane tipped her head on one side, then grinned. ‘Give me a minute.’

It took her five, during which time Julia heard her talking on the phone in the study next door, then she came back with a self-satisfied smile.

‘Sorted. Pete’s got a friend, John Blake, who’s going to be working in Chicago for a year. He’d found someone to act as a caretaker for the house, but it’s fallen through, and he’s been desperately looking for someone else.’

‘Why doesn’t he just let it?’

‘Because he’ll be coming and going, so he can’t really. But it’s a super house, all your running and living expenses will be paid, all you have to do is live in it, not have any wild parties, and call the plumber if necessary. Oh, and feed and walk the dog. Are you OK with dogs?’

She nodded. ‘I love dogs. I’ve always wanted one.’

‘Brilliant. And Murph’s a sweetie. You’ll love him, and the house. It’s called Rose Cottage, it’s got an absolutely gorgeous garden, and the best thing is it’s only three miles from here, so we can see lots of each other. It’ll be fun.’

‘But what about the baby? Won’t he mind?’

‘John? Nah. He loves babies. Anyway, he’s hardly ever home. Come on, we’re going to see him now.’

CHAPTER ONE

‘I’VE found her.’

Max froze.

It was what he’d been waiting for since June, but now—now he was almost afraid to voice the question. His heart stalling, he leaned slowly back in his chair and scoured the investigator’s face for clues. ‘Where?’ he asked, and his voice sounded rough and unused, like a rusty hinge.

‘In Suffolk. She’s living in a cottage.’

Living. His heart crashed back to life, and he sucked in a long, slow breath. All these months he’d feared…

‘Is she well?’

‘Yes, she’s well.’

He had to force himself to ask the next question. ‘Alone?’

The man paused. ‘No. The cottage belongs to a man called John Blake. He’s working away at the moment, but he comes and goes.’

God. He felt sick. So sick he hardly registered the next few words, but then gradually they sank in. ‘She’s got what?’

‘Babies. Twin girls. They’re eight months old.’

‘Eight—?’ he echoed under his breath. ‘So he’s got children?’

He was thinking out loud, but the PI heard and corrected him.

‘Apparently not. I gather they’re hers. She’s been there since mid-January last year, and they were born during the summer—June, the woman in the post office thought. She was more than helpful. I think there’s been a certain amount of speculation about their relationship.’

He’d just bet there had. God, he was going to kill her. Or Blake. Maybe both of them.

‘Of course, looking at the dates, she was presumably pregnant when she left you, so they could be yours—or she could have been having an affair with this Blake character before.’

He glared at the unfortunate PI. ‘Just stick to your job. I can do the maths,’ he snapped, swallowing the unpalatable possibility that she’d been unfaithful to him before she’d left. ‘Where is she? I want the address.’

‘It’s all in here,’ the man said, sliding a large envelope across the desk to him. ‘With my invoice.’

‘I’ll get it seen to. Thank you.’

‘If there’s anything else you need, Mr Gallagher, any further information—’

‘I’ll be in touch.’

‘The woman in the post office told me Blake was away at the moment, if that helps,’ he added quietly, and opened the door.

Max stared down at the envelope, hardly daring to open it. But, when the door clicked softly shut behind the PI, he eased up the flap, tipped it and felt his breath jam in his throat as the photos spilled out over the desk.

Oh lord, she looked gorgeous. Different, though. It took him a moment to recognise her, because she’d grown her hair and it was tied back in a ponytail, making her look younger and somehow freer. The blonde highlights were gone, and it was back to its natural soft golden-brown, with a little curl in the end of the ponytail that he wanted to thread his finger through and tug, just gently, to draw her back to him.

Crazy. She’d put on a little weight, but it suited her. She looked well and happy and beautiful, but oddly, considering how desperate he’d been for news of her for the last year—one year, three weeks and two days, to be exact—it wasn’t Julia who held his attention after the initial shock. It was the babies sitting side by side in a supermarket trolley. Two identical and absolutely beautiful little girls.

His? It was a distinct possibility. He only had to look at the dark, spiky hair on their little heads, so like his own at that age. He could have been looking at a photo of himself.

Max stared down at it until the images swam in front of his eyes. He pressed the heels of his hands against them, struggling for breath, then lowered his hands and stared again.

She was alive—alive and well—and she had two beautiful children.

Children that common sense would dictate were his.

Children he’d never seen, children he’d not been told about, and suddenly he found he couldn’t breathe. Why hadn’t she told him? Would he ever have been told about them? Damn it, how dared she keep them a secret from him? Unless they weren’t his…

He felt anger building inside him, a terrible rage that filled his heart and made him want to destroy something the way she’d destroyed him.

The paperweight hit the window and shattered, the pieces bouncing off the glass and falling harmlessly to the floor, and he bowed his head and counted to ten.

‘Max?’

‘He’s found her—in Suffolk. I have to go.’

‘Of course you do,’ his PA said soothingly. ‘But take a minute, calm down, I’ll make you a cup of tea and get someone to pack for you.’

‘I’ve got a bag in the car. You’ll have to cancel New York. In fact, cancel everything for the next two days. I’m sorry, Andrea, I don’t want tea. I just want to see my—my wife.’

And the babies. His babies.

She blocked his path. ‘It’s been over a year, Max. Another ten minutes won’t make any difference. You can’t go tearing in there like this, you’ll frighten the life out of her. You have to take it slowly, work out what you want to say. Now sit down. That’s it. Did you have lunch?’

He sat obediently and stared at her, wondering what the hell she was talking about. ‘Lunch?’

‘I thought so. Tea and a sandwich—and then you can go.’

He stared after her—motherly, efficient, bossy, organising—and deeply, endlessly kind, he realised now—and felt his eyes prickle again.

He couldn’t just sit there. He crunched over the paperweight and placed his hands flat on the window, his forehead pressed to the cool, soothing glass. Why hadn’t he known? How could she have kept something so significant from him for so long?

He heard the door open and Andrea return.

‘Is this her?’

‘Yes.’

‘And the babies?’

He stared out of the window. ‘Yes. Interesting, isn’t it? It seems I’m a father, and she didn’t even see fit to tell me. Either that or she’s had an affair with my doppelganger, because they look just like I did.’

She put the tray down, tutted softly and then, utterly out of the blue, his elegant, calm, practical PA hugged him.

He didn’t know what to do for a second. It was so long since anyone had held him that he was shocked at the contact. But then slowly he lifted his arms and hugged her back, and the warmth and comfort of it nearly unravelled him. Resisting the urge to hang on, he stepped back out of her arms and turned away, dragging in air and struggling for control of the situation.