Полная версия:

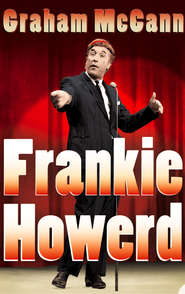

Frankie Howerd: Stand-Up Comic

GRAHAM MCCANN

Frankie Howerd

Stand-Up Comic

Copyright

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This edition published by Harper Perennial 2005

First published by Fourth Estate 2004

Copyright © Graham McCann 2004

Graham McCann asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9781841153117

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2016 ISBN: 9780007369249 Version: 2016-02-08

Dedication

For Mic,

who believed I could write it, and

Vera and Silvana, who believed I could complete it.

Epigraph

I donât go for this business of the broken-hearted clown.

Because I think a broken-hearted clown would be a damn sight more broken-hearted if he wasnât a clown.

FRANKIE HOWERD

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

THE PROLOGUE

ACT I: FRANCIS

1 St Francis

2 A Stuttering Start

3 Army Camp

ACT II: FRANKIE

4 Meet Scruffy Dale

5 Variety Bandbox

6 The One-Man Situational Comedy

INTERMISSION: THE YEARS OF DARKNESS

7 Ever-Decreasing Circles

8 Dennis

9 The Breakdown

ACT III: THE COMEBACK

10 Re. Establishment

11 Musicals

12 Movies

ACT IV: THE CULT

13 Carry On, Plautus

14 The Closeted Life

15 Cult Status

THE EPILOGUE

Keep Reading

List of Performances

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Notes

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

THE PROLOGUE

Now listen, brethren. Before we begin the eisteddfod, Iâd like to make an appeal â¦

Now, er, Ladies and Gentlemen. Harken. Now, ah, no: harken.

Listen, now. Harr-ken. Harr-ever-so-ken! 1

It was not so much the look of someone who did not belong. It was more the look of someone who did not belong up there.

He looked as if he belonged in the audience. He looked as if he had strayed on to the stage by mistake. He fiddled with the fraying fringe of his chestnut-brown hairpiece, fidgeted with the folds of his chocolate-brown suit (âMake meself comfy â¦â), and then he started: âI just met this woman â no, oh no, donât, please, donât laugh. No. Liss-en!â He did not sound as if he was performing under a proscenium arch. He sounded as if he was gossiping over a garden wall.

That was Frankie Howerd. He did not seem like the other stand-up comedians. He seemed more like one of us.

The other stand-up comics of his and previous eras came across as either super-bright or super-dim.2 Most of them, like Max Miller, were peacocks: slick and smart and salesman-sharp, they were happy to appear far more experienced, more assured and more articulate than any of those who were seated down in the stalls. The odd one or two, such as Tom Foy, were strange little sparrows: slow, fey and almost painfully gauche, they were the kind of grotesque, cartoon-like fools to whom even fools could feel superior.

No stand-up, until Howerd, came over as recognisably real: neither too arch a âcharacterâ nor too obvious a âturnâ, but almost as believably unrehearsed, untailored, unshowy, unsure and undeniably imperfect as the rest of us. Frankie Howerd, when he arrived, was genuinely different. He was the first British stand-up to resemble a real person, rather than just a performer.

He became, as a result, the most subversive clown in the country. What made him so subversive was not the fact that he dared to make a mockery of himself â any old clown can do that â but rather the fact that he dared to make a mockery of his own profession. He was the clown who made a joke out of the job of clowning.

Everything about the vocation, he suggested, was onerous, absurd, unrewarding and unbearably demeaning. He bemoaned, for example, the routine maltreatment meted out by the management: âIâve had a shocking week. Shocking. Whatâs today? Tuesday. It was last Monday then. The phone rang, and it was, er, yâknow, um, the bloke who runs the BBC. Whatsisname? You know: âThingâ. Yeah. Anyway, he was on the phone, you see. So I accepted the charge â¦â

He also complained about his ill-fitting stage clothes: âOoh, my trousers are sticking to me tonight! Are yours, madam? Then wriggle. Thereâs nothing worse than sitting in agony.â Similarly, he never hesitated to express the full extent of his resentment at being saddled with such an ancient and incompetent accompanist: âNo, donât laugh. Poor soul. No, donât â it might be one of your own. [To accompanist] It is chilly! Yehss, âtis! [To audience] Chilly? Iâm sweating like a pig!â He also always made a point of acknowledging the poverty of his material: âWhat do you expect at this time of night? Wit?â

He never, in short, left his audience in the slightest doubt that he would have much preferred to have been doing something â anything â else. âOh,â he would cry, âI wish I could win the pools!â

He did not even bother to turn up with, in any conventional sense of the term, an act. His act was all about his lack of an act, his artlessness the slyest sign of his art:

Now, Ladies and Gentle-men â no, look, donât mess about, I donât feel in the mood. No. I want to tell you â Iâve had a terrible time of it this week, and, er, I havenât been able to get much for you â so donât expect too much, will you? No, but I always try to do my best, as you know, but, oh, this week â itâs been too much. Still, Iâve managed to knock up something â Iâll do my best, I know you want to laugh â but, oh, the time Iâve had this week! Still, I wonât bother you with it â I know youâve got your own troubles and â mind you, it was my own fault â¦

These rambling perambulations revolutionised the medium of the stand-up comedian. They turned it into something much more intimate, intriguing and naturalistic, having less to do with the telling of gags and more to do with the sharing of stories.

So great has been his influence that nowadays, more than a decade after his death, the approach seems more like the norm than the exception. We have come to warm most readily to those who convey the core of their humour through character and context, while we have cooled on those who continue to rely on the creaky old conveyor belt of patently contrived one-liners.

Howerd, however, was the one who set the fresh trend. His decision to adopt such an extraordinarily âordinaryâ pose and persona back in the considerably less flexible show-business world of the mid-twentieth-century took real wit, imagination and guts. While his contemporaries remained content to step back and soak up the applause, he chose to step forward and make a connection.

That was his real achievement, his great achievement. Frankie Howerd really did make a difference. He was so much more than the casually patronised âcultâ figure, âcampâ icon and Carry On fellow-traveller who, according to far too many of the predictably trivial posthumous tributes and all of the tiresome tabloid nudges and winks, bequeathed us little more than a handful of over-familiar sketch shows and sitcoms, a few quaintly hoary catchphrases (all of which, thanks to their increasingly robotic repetition, have long since calcifìed into mirthless cliché) and a dubious fund of dusty double entendres.3

Frankie Howerd â the real Frankie Howerd â was truly special. A brilliantly original, highly skilful and wonderfully funny stand-up comedian â whose talent and impact were as prodigious and profound, in their own way, as those of Bob Hope, Jack Benny or any of the other internationally recognised greats â he deserves to be remembered, respected and celebrated as such.

Consider the extraordinary career: stretching all the way from the late 1940s to the early 1990s, and encompassing everything from the demise of music-hall and the rise of radio to the supremacy of television and the emergence of home video. Howerd stamped his signature upon each one of the media he mastered.

Consider, too, the incredible comebacks: written off by the producers, the press and more than a few of his fellow-performers on not one, not two, but on three profoundly harrowing and humiliating occasions, he returned each time not only to recover all of his old fame, fans and professional pride, but also to find himself a fresh generation of followers. Seldom has there been such a frail yet faithful fighter.

Consider, most of all, the exceptional craft. One critic called the on-stage Howerd âa very clever man pretending not to beâ, and few descriptions could have been more apt. His comedy turned the traditional tapestry upside down: we were shown only the messiness â merely the âumsâ and the âersâ and the âahsâ â while the elaborate pattern â what Howerd liked (in private) to call âa beauty of delivery, a beauty of rhythm and timing â like a piece of musicâ4 â was kept well-hidden.

He acted more or less how most of us felt (and feared) that we would act, should we ever find ourselves forced into the spotlight up there instead of staying hidden in the dark down here. All of the key ingredients of Britainâs peculiar post-colonial character â the defiant amateurism, the nagging self-doubt, the public primness and the private sauce â were caught squirming in the spotlight, stuffed inside a badly-fitting brown suit topped off by an exhausted-looking toupee.

The implicit admission was unmistakeable: âIâm afraid Iâm just not up to this job!â The phases of failure were similarly familiar: the nerve would falter, the words would fail and the half-hearted gags would invariably fall horribly, hopelessly flat. No one born British was ever moved to wonder why there was so much âOh no!â in the show, and so little âOh yes!â That was life. That was our life.

Most, if not all, of the humour sprang from this world-weary acceptance of our own insurmountable imperfection. Whereas âproperâ performers would always insist on being allowed to entertain you, Frankie Howerd was prepared to advise you to please yourselves.

The net effect was the creation of one of the most openly, endearingly, reassuringly human performances that modern comedy has ever produced. Every grumble, every groan, every grimace and every sudden solemn squeak of admonition would coax from us one more furtive snigger of recognition. We knew what he knew, and what he knew was us.

Howerd knew our sort all right. It is time now for us to get to know him.

ACT I: FRANCIS

Nervy â that was me. Nerves were the only thing that came easily.

CHAPTER 1

St Francis

Poor soul.

If we were to begin where Frankie Howerd would have wanted us to begin, we would be five years out of date. According to all of his own public accounts,1 Frankie Howerd (whose proper surname, incidentally, was spelt âHowardâ) was born on 6 March 1922. In truth, he was not: being painfully aware of the age-based prejudices of his own precarious profession, he arranged, in the first of many self-inflicted imprecisions, to have his real infancy erased.

The authentic beginning had actually arrived back on 6 March 1917, when Francis Alick Howard â the first child of the 30-year-old Francis Alfred William Howard and his 29-year-old wife, Edith Florence Morrison â was born in the City Hospital in York. An early photograph recorded the sight of a broad-browed, blown-cheeked and somewhat reproachful-looking baby, with a downy dome of fair hair, a pair of large protruding ears, and a mouth already puckered up into the now-familiar outraged pout (âI was,â the famous adult would always insist, âquite beautifulâ2).

The Howardsâ first family home was situated at 53 Hartford Street, a small but rather smart red-bricked terraced house not far from the city centre in the Fulford district of York. Both parents, right from the start, went out to earn a wage. Francis Snr was a private in the 1st Royal Dragoons; following in the footsteps of his father (a former sergeant at the Royal Military College at Sandhurst), he served as a staff clerk.3 Edith, meanwhile, laboured long and hard as a âcream chocolate makerâ at the local Rowntree confectionery factory.

Before their child had the chance to acquire any real awareness of his loose northern roots â the solitary memory to survive to later life, apparently, would be of him tumbling down some stairs and bumping his head4 â the family was obliged to move down south. In the summer of 1919, when the baby Francis had reached the age of two-and-a-half, his father was transferred to the Royal Artillery, promoted to sergeant and posted to the Woolwich Barracks at Greenwich in south-east London.

The need for the switch had been accepted with some enthusiasm by the newly-elevated Sergeant Howard, who recognised that he was not only taking a modest but none the less welcome step up the professional ladder, but was also, as someone Plumstead born and bred, on his way back to a place that struck him as so much more like âhomeâ. The acceptance of such a rude upheaval almost certainly came rather harder, however, to his wife, Edith, whose entire life, up until this point, had been lived in close proximity to her mother, father and seven siblings within the confines of the comforting walls of York.

The Howardsâ new family home was located at 19a Arbroath Road in Eltham (which in those days was a relatively quiet and rural area situated on the borders of London and Kent). Once the Howards had actually settled in, however, it soon began to feel like a home without a family. The problem was that Frank Snr had to spend his weekdays based six miles away at the Royal Artillery barracks, while Edith was left on her own in an unfamiliar environment to bring up their infant son. Although the ostensible head of the household would duly return, with his wage packet, each weekend to be with his wife, the stark contrast in their newly separate styles of life â his brightened by the clarity of its routine and the quality of its camaraderie, hers dulled by a creeping sense of loneliness and a palpable loss of purpose â would in time breed tensions deep enough to shake the base of the bond between them.

For a while, however, the couple worked hard to find ways to remain committed. Frank Snr not only behaved responsibly in his role as the familyâs sole breadwinner, but also invested a fair amount of effort into trying to make what little time he shared with his wife and son seem reasonably worthwhile. Edith, for her part, bit her tongue on all of the bad days, savoured each one of the few that were good, and buried herself in the business of being both a homemaker and a mother.

It was not just young Francis on whom she would dote. A second son, called Sidney, was born in April 1920, closely followed, in October 1921, by the birth of a baby daughter named Edith Bettina but known to everyone as Betty. Edith adored them all, and, making a virtue out of a necessity, she soon came to relish her role as the familyâs singular parental figure.

As a mother, she gave her children a generous measure of encouragement and affection. A short, slender woman with dark, vaguely âgypsyishâ good looks, discreet but deeply sincere religious beliefs and a quietly cheerful disposition, she made sure that her family had fun, sharing with them her great love of music, humour and the art of make-believe. When she could afford to she would take the children out, and when the money was tight she would stay with them inside, but, wherever they were, she always ensured that they would laugh, play and consider themselves to have been richly and warmly entertained.

Assuming those duties that had been neglected by their absent father, she also instilled a fairly strong sense of discipline in each of her children, and tried to teach them a simple but solid code of conduct. Echoing many of the lessons she had learned from her own father, David (a stern and very strict Scottish Presbyterian), she would always stress the importance of industry, frugality and self-reliance, and insisted on treating others with a proper sense of fairness and respect.

Of all her three children, it was Frank (as he preferred to be addressed) who appeared the one most eager to please her, as well as the one who was most closely attuned to her own personality and point of view. He loved to sit and listen to her singing snatches from all of her favourite musical comedies (âmy first impression of show-businessâ), felt thrilled when she showed so much enthusiasm for any performance that emerged from out of his âidiot world of fantasyâ, and was delighted to find that he shared her âway-out sense of humourâ.5 In short, he adored her.

Even after he had started attending school â the local Gordon Elementary6 â and begun to acquire a broader range of friends, potential role models and adult authority figures, this special allegiance stayed as firm and true as ever. He would remain, totally and openly, Edithâs son.

He had never been, in any meaningfully emotional sense of the term, âFrankâs sonâ. Whereas young Sidney and (to a lesser extent) Betty would greet each fleeting visit from their strangely unfamiliar father with a fair degree of enthusiasm and excitement, their older brother never showed any pleasure at being in his presence, regarding him coldly instead as little more than a âgatecrasherâ.7

When Frankie Howerd came to look back on this formative stage in his life, he would confess that the only thing that he had shared willingly with his father (aside, perhaps, from their fair-coloured hair) was the recognition of âa singular lack of rapportâ. Frank Snr had seemed, at best, âa strangerâ, and, at worst, a rival: âI positively resented his âintrusionâ in the relationship I had with my mother.â8

He also genuinely resented the emotional pain he could see that his father was causing her. It was hard enough on Edith when the sum total of the time she could hope to share with her husband amounted to no more than two days out of every seven. It was harder still when he was transferred to the Army Educational Corps, and began travelling all over the country, and spending far longer periods away, fulfilling his duties as an instructor and supervisor of young soldiers.9 These many absences certainly hurt her, but then so too did her husbandâs apparent belief that the mere provision of his money would more than make up for the patent lack of his love.

Even if her eldest son failed to understand fully the intimate nature of the causes, he was mature enough to appreciate the true severity of the effects. His beloved mother was suffering, and his father was the man who was making her suffer.

This alone might have been sufficient to explain the adult Frankie Howerdâs apparent aversion to any mention of his father, but, according to several of those to whom he was close,10 there was another, far darker, reason for the denial: his father, he would claim, was a âsadistâ who not only used to âdisciplineâ his eldest son by locking him in a cupboard, but also (on more than one occasion during those brief and intermittent visits back to their home in Arbroath Road) subjected him to abuse of a sexual nature. While there is no conclusive proof that this is true, Howerd himself remained adamant, in private, that such abuse really did take place.11

The story, if one accepts it, certainly makes it hard not to reread the fragmentary autobiographical account of the first decade or so in his life as a coded insight into a profoundly traumatic time. So many tiny details about that âincredibly shy and withdrawn childâ12 â including a fear of authority that grew so great as to make young Frank appear âconscientious to the point of stupidityâ; an early need to go off on long solitary walks âjust to be alone in my own private, dream worldâ; the unshakeable conviction that he was âugly and useless to man and beastâ; and the longing for a place âin which shyness and nerves did not appear to exist â â seem to fit the familiar picture of someone struggling through the private hell that accompanied such abuse.13

It also appears telling, from this perspective, that towards the end of this period14 Frank suddenly acquired a serious stammer. It first started to be noticeable, he would recall, whenever he was âfrightened or under stress, and in an unfamiliar environmentâ: âIâd gabble and garble. Always a very fast talker, Iâd repeat words and run them together when this terror came upon me.â15

Failing health would gradually diminish any real physical threat posed by Frank Snr. Invalided out of the Army at the start of the 1930s following the discovery of a hole in one of his lungs,16 he struggled on, increasingly frail and emphysemic, as a clerk at the Royal Arsenal munitions factories until his death, in 1935, at the age of forty-eight. Memories of past threats, on the other hand, would prove impossible for his son to expunge. The real damage had already been done.

When, in 1969, a young journalist had the temerity to quiz Howerd on his feelings about his late father, he merely responded with a slightly too edgy, and therapy-friendly, attempt at a casual putdown: Frank Snr, he muttered, âwas all right. He was away a lot. Look, I didnât let you in here to ask me Freudian questions.â17 Seven years later, however, there was a far more obvious display of disdain in his autobiography, which all but edited out the father from the story of the sonâs life. In stark contrast to its lovingly lavish treatment of Edith, not one picture of him was included, and no description was provided: aside from the acknowledgement (apropos of nothing in particular) that Frank Snr was âessentially a practical manâ,18 the only recognition of his fatherâs existence was to underline his absence: âMost people have a mother and father,â Howerd observed, before adding, more with a sigh of relief than any hint of regret: âI seemed to have only a mother.â19