Полная версия:

Salonica, City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and Jews

SALONICA

CITY OF GHOSTS

Christians, Muslims and Jews 1430–1950

MARK MAZOWER

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This edition published by Harper Perennial 2005

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2004

Copyright © Mark Mazower 2004

Mark Mazower asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007120222

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2016 ISBN: 9780007383665

Version: 2016-08-24

Dedication

To Marwa

Contents

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

LIST OF MAPS

INTRODUCTION

PART ONE: The Rose of Sultan Murad

1 Conquest, 1430

2 Mosques and Hamams

3 The Arrival of the Sefardim

4 Messiahs, Martyrs and Miracles

5 Janissaries and Other Plagues

6 Commerce and the Greeks

7 Pashas, Beys and Money-lenders

8 Religion in the Age of Reform

PART TWO: In the Shadow of Europe

9 Travellers and the European Imagination

10 The Possibilities of a Past

11 In the Frankish Style

12 The Macedonia Question, 1878–1908

13 The Young Turk Revolution

PART THREE: Making the City Greek

14 The Return of St Dimitrios

15 The First World War

16 The Great Fire

17 The Muslim Exodus

18 City of Refugees

19 Workers and the State

20 Dressing for the Tango

21 Greeks and Jews

22 Genocide

23 Aftermath

CONCLUSION: The Memory of the Dad

GLOSSARY

INDEX

NOTES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

PRAISE

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

List of Maps

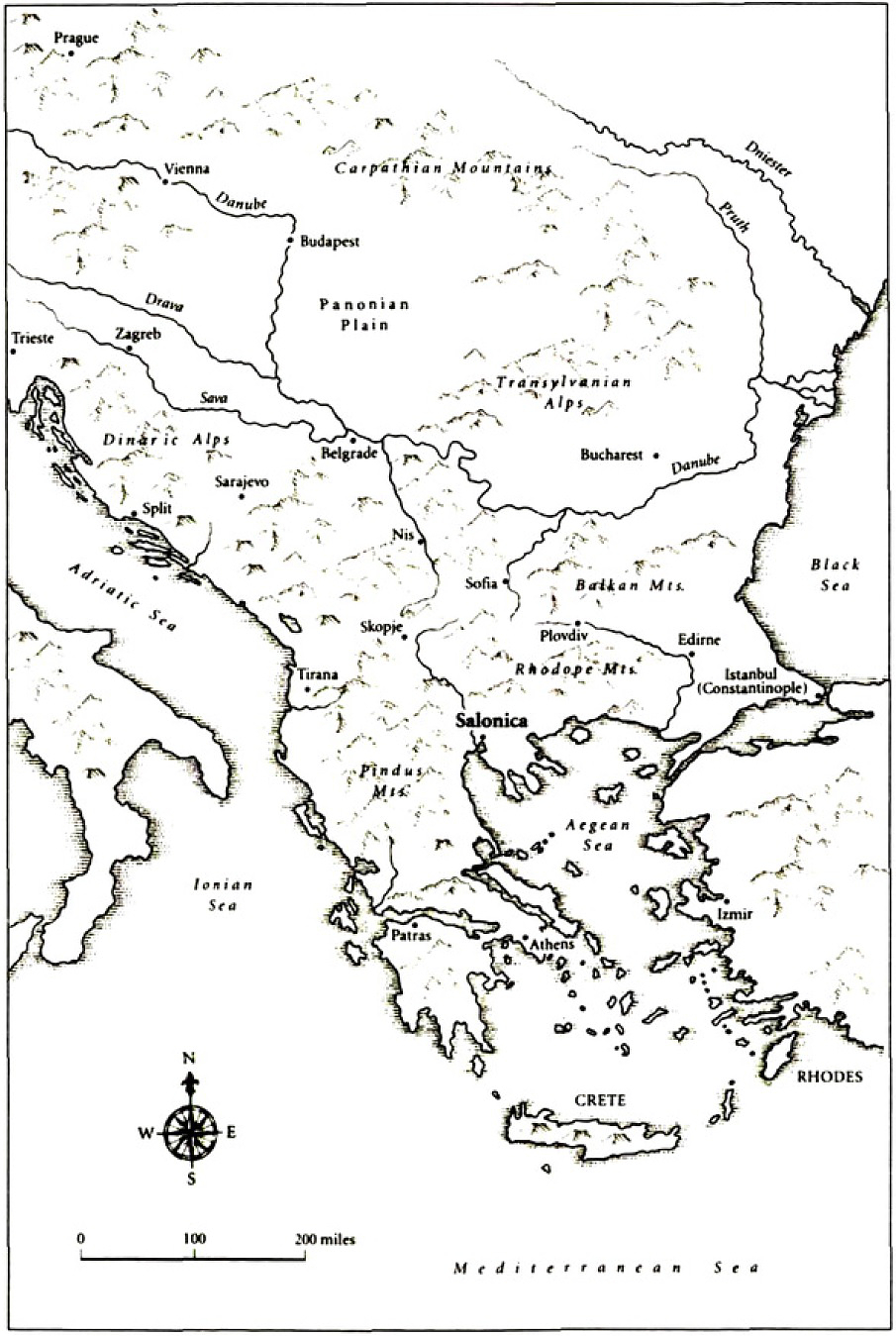

The topography of the Balkans.

Inside the Ottoman city.

The first map of the Ottoman city, 1882, showing the new sea frontage.

The late Ottoman city and its surroundings, c.1910.

Area destroyed by the 1917 fire.

After the fire: the 1918 Plan.

The Balkans after 1918.

The 1929 Municipal City Plan.

Introduction

Beware of saying to them that sometimes cities follow one another on the same site and under the same name, born and dying without knowing one another, without communicating among themselves. At times even the names of the inhabitants remain the same, and their voices’ accent, and also the features of the faces; but the gods who live beneath names and above places have gone off without a word and outsiders have settled in their place.

ITALO CALVINO, Invisible Cities1

THE FIRST TIME I visited Salonica, one summer more than twenty years ago, I stepped off the Athens train, shouldered my rucksack, and left the station in search of the town. Down a petrol-choked road, I passed a string of seedy hotels, and arrived at a busy crossroads: beyond lay the city centre. The unremitting heat, and the din of the traffic reminded me of what I had left several hours away in Athens but despite this I knew I had been transported into another world. A mere hour or so to the north lay Tito’s Yugoslavia and the checkpoints at Gevgeli or Florina; to the east were the Rhodope forests barring the way to Bulgaria, the forgotten Muslim towns and villages of Thrace, and the border with Turkey. From the moment I crossed the hectic confusion of Vardar Square – ‘Piccadilly Circus’ for British soldiers in the First World War – ignoring the signposts that urged me out of the city in the direction of the Iron Curtain, I sensed the presence of a different Greece, less in thrall to an ancient past, more intimately linked to neighbouring peoples, languages and cultures.

The crowded alleys of the market offered shade as I pushed past carts piled high with figs, nuts, bootleg Fifth Avenue shirts and pirated cassettes. Tsitsanis’s bouzouki strained the vendors’ tinny speakers, but it was no competition for the clarino and drum with which gypsy boys were deafening diners in the packed ouzeris of the Modiano food market. Round the tables of Myrovolos Smyrni [Sweet-smelling Smyrna], its very name an evocation of the glories and disasters of Hellenism’s Anatolian past, tsipouro and mezedes were smoothing the passage from work to siesta. There were fewer back-packers in evidence here than in the tourist dives around the Acropolis, more housewives, porters and farmers on their weekly trip into town. Did I really see a dancing bear performing for onlookers in the meat market? I certainly did not miss the flower-stalls clustered around the Louloudadika hamam (known also according to the guidebooks as the Market Baths, the Women’s Baths, or the Yahudi Hamam, The Bath of the Jews), the decrepit spice warehouses on Odos Egyptou [Egypt Street], the dealers still installed in the old fifteenth-century multi-domed bezesten. This vigorous commercialism put even Athens to shame: here was a city which had remained much closer to the values of the bazaar and the souk than anything to be seen further south.

The topography of the Balkans.

Athens itself had eliminated the traces of its Ottoman past without much difficulty. For centuries it had been little more than an overgrown village so that after winning independence in 1830 Greece’s rulers found there not only the rich cultural capital invested in its ancient remains by Western philhellenism, but all the attractions of something close to a blank slate so far as the intervening epochs were concerned. Salonica’s Ottoman past, on the other hand, was a matter of living memory, for the Greek army had arrived only in 1912 and those grandmothers chatting quietly in the yards outside their homes had probably been born subjects of Sultan Abdul Hamid. The still magnificent eight-mile circuit of ancient walls embraced a densely thriving human settlement whose urban character had never been in question, a city whose history reached forward from classical antiquity uninterruptedly through the intervening centuries to our own times.

Even before one left the packed streets down near the bay and headed into the Upper Town, tiny medieval churches half-hidden below ground marked the transition from classical to Byzantine. It did not take long to discover what treasures they contained – one of the most resplendent collections of early Christian mosaics and frescoes to be found anywhere in the world, rivalling the glories of Ravenna and Istanbul. A Byzantine public bath, hidden for much of its existence under the accumulated top-soil, still functioned high in the Upper Town, near the shady overgrown garden which hid tiny Ayios Nikolaos Orfanos and its fourteenth-century painted narrative of the life of Christ. The Rotonda – a strange cylindrical Roman edifice, whose multiple re-incarnations as church, mosque, museum and art centre encapsulated the city’s endless metamorphoses – contained some of the earliest mural mosaics to be found in the eastern Mediterranean. Next to it stood an elegant pencil-thin minaret, nearly one hundred and twenty feet tall.

Like many visitors before me, I found myself particularly drawn to the Upper Town. There, hidden inside the perimeter of the old walls was a warren of precipitous alleyways sometimes ending abruptly, at others opening onto squares shaded by plane trees and cooled by fountains. One had the sense of entering an older world whose life was conducted according to different rhythms: cars found the going tougher, indeed few of them had yet mastered the cobbled slopes. Pedestrians took the steep gradients at a leisurely pace, pausing frequently for rest: despite the heat, people came to enjoy the panoramic views across the town and over the bay. Down below were the office blocks and multi-storey apartment buildings of the postwar boom. But here there were few signs of wealth. Abutting the old walls were modest whitewashed homes in brick or wood – often no more than a single small room with a privy attached: a pot of geraniums brightened the window-ledge, a rag rug bleached by the sun served as a door mat, clotheslines were stretched from house to house. Their elderly inhabitants were neatly dressed. Later I realized most had probably lived there since the 1920s, drawn from among the tens of thousands of refugees from Asia Minor who had settled in the city after the exchange of populations with Turkey. Their simple homes contrasted with the elegantly dilapidated villas whose overhanging upper floors and high garden walls still lined many streets; the majority, once grand, had been badly neglected: their gabled roofs had caved in, their shuttered bedrooms lay open to public view, and one caught spectacular glimpses of the city below through yawning gaps in their frontage. By the time I first saw them most had been abandoned for decades, for their Muslim owners had left the city when the refugees had arrived. The cypresses, firs and rosebushes in their gardens were overgrown with ivy and creeping vines, their formerly bright colours had faded into pastel shades of yellow, ochre and cream. Here were vestiges of a past that was absent from the urban landscape of southern Greece – Turkish neighbourhoods that had outlived the departure of their inhabitants; fountains with their dedicatory inscriptions intact; a dervish tomb, now shuttered and locked.

With later visits, I came to see that these traces of the Ottoman past offered a clue to Salonica’s central paradox. True, it could point, as Athens could not, to more than two thousand years of continuous urban life. But this history was decisively marked by sharp discontinuities and breaks. The few Ottoman monuments that had endured were a handful compared with what had once existed. The old houses were falling down and within a decade many of them had collapsed or been demolished. Some buildings have been recently restored and visitors can see inside the magnificent fifteenth-century Bey Hamam, the largest Ottoman baths in Greece, or admire the distinguished mansion now used as a local public library in Plateia Romfei. But otherwise the Ottoman city has vanished, exciting little comment except among preservationists and scholars.

Change is, of course, the essence of urban life and no successful city remains a museum to its own past. The expansion of the docks since the Second World War has obliterated the seaside amusement park – the Beshchinar gardens, or Park of the Princes – where the city’s inhabitants refreshed themselves for generations; today it is commemorated only in a nearby ouzeri of the same name. In the deserted sidings of the old station, prewar trams and elderly railway carriages are slowly disintegrating. Even the infamous swampy Bara – once the largest red light district in eastern Europe – survives only in the fond memories of a few ageing locals, in local belles-lettres, and in its streets – still bearing the old names, Afrodite, Bacchus – which now house nothing more exciting than car rental agencies, garages and tyre-repair shops.

But ridding the city of its brothels is one thing and eradicating the visible traces of five centuries of urban history is quite another. What, I wondered, did it do to a city’s consciousness of itself – especially to a city so proud of its past – when substantial sections were at best allowed to crumble away, at worst written out of the record? Had this happened by accident? Could one blame the great fire of 1917 that had destroyed so much of its centre? Or did the forced exchange of populations in 1923 – when more than thirty thousand Muslim refugees departed, and nearly one hundred thousand Orthodox Christians took their place – suddenly turn one city into a new one? Was the sense of urban continuity, in other words, which had so powerfully attracted me to Salonica at the outset, an illusion? Perhaps there was another urban history waiting to be written in which the story of continuity would have to be told rather differently, a tale not only of smooth transitions and adaptations, but also of violent endings and new beginnings.

For there was another vanished element of the city’s past which I was also beginning to learn about. On the drive into town from the airport, I had caught intriguing glimpses of substantial nineteenth-century villas hidden behind rusting railings and overgrown weeds amid the rows of postwar suburban apartment blocks. The palatial three-storey pile in its own pine-shaded estate, now the main seat of the Prefecture, turned out to have been originally the home of wealthy nineteenth-century Jewish industrialists, the Allatinis; this was where Sultan Abdul Hamid had been kept when he was deposed by the Young Turks and exiled to the city in 1909. Along the same road was the Villa Bianca, an opulently outsize Swiss chalet, home of the wealthy Diaz-Fernandes family. On the drive into town, one passed a dozen or more of these shrines to the eclectic taste of its fin-de-siècle elite – Turkish army officers, Greek and Bulgarian merchants, and Jewish industrialists.

Turks and Bulgarians figured prominently in the histories of Greece I had read, usually as ancestral enemies, but the Jews were in general remarkable only for their absence, enjoying little more than a bit-part in the central and all-important story of modern Greece’s emergence onto the international stage. In Salonica, however, it would be scarcely an exaggeration to say that they had dominated the life of the city for many centuries. As late as 1912 they were the largest ethnic group and the docks stood silent on the Jewish Sabbath. Jews were wealthy businessmen; but many more were porters and casual labourers, tailors, wandering street vendors, beggars, fishermen and tobacco-workers. Today the only traces of their predominance that survive are some names – Kapon, Perahia, Benmayor, Modiano – on faded shopfronts, Hebrew-lettered tombstones piled up in churchyards, an old people’s home and the community offices. There is a cemetery, but it is a postwar one, buried in the city’s western suburbs.

Here as elsewhere it was the Nazis who brought centuries of Jewish life to an abrupt end. When Kurt Waldheim, the Austrian politician who had served in the city as an army officer, was accused of being involved in the deportations, I came back to Salonica to talk to survivors of Auschwitz, resistance fighters, the lucky ones who had gone underground or managed to flee abroad. A softly-spoken lawyer stood with me on the balcony of his office and we looked down onto the rows of parked cars in Plateia Eleftherias [Freedom Square] where he had been rounded up with the other Jewish men of the city for forced labour. Two elderly men, not Jewish, whom I bumped into on Markos Botsaris Street, told me about the day the Jews had been led away in 1943: they were ten at the time, they said, and afterwards, they broke into their homes with their friends and found food still warm on the table. A forty-year-old woman who happened to sit next to me on the plane back to London had grown up after the war in the quarter immediately above the old Jewish cemetery: she remembered playing in the wreckage of the graves as a child, with her friends, looking for buried treasure, shortly before the authorities built the university campus over the site. Everyone, it seemed, had their story to tell, even though at that time what had happened to the city’s Jews was not something much discussed in scholarly circles.

A little later, in Athens, I came across several dusty unopened sacks of documents at the Central Board of Jewish Communities. When I examined them, I found a mass of disordered papers – catalogues, memoranda, applications and letters. They turned out to be the archives of the wartime Service for the Disposal of Israelite Property, set up by the Germans in those few weeks in 1943 when more than forty-five thousand Jews – one fifth of the city’s entire population – were consigned to Auschwitz. These files showed how the deportations had affected Salonica itself by triggering off a scramble for property and possessions that incriminated many wartime officials. I started to think about deportations in general, and the Holocaust in particular, not so much in terms of victims and perpetrators, but rather as chapters in the life of cities. The Jews were killed, almost all of them: but the city that had been their home grew and prospered.

The accusation that Waldheim had been involved in the Final Solution – unfounded, as it turned out – reflected the extent to which the Holocaust was dominating thinking about the Second World War. Sometimes it seemed from the way people talked and wrote as though nothing else of any significance had happened in those years. In Greece, for example, two other areas of criminal activity – the mass shootings of civilians in anti-partisan retaliations, and the execution of British soldiers – were far more pertinent to Waldheim’s war record. There were good reasons to deplore this state of cultural obsession. It quickly made the historian subject to the law of diminishing returns. It also turned history into a form of voyeurism and allowed outsiders to sit in easy judgement. I sometimes felt that I myself had become complicit in this – scavenging the city for clues to destruction, ignoring the living for the dead.

Above all, unremitting focus upon the events of the Second World War threatened to turn a remarkable chapter in Jewish, European and Ottoman history into nothing more than a prelude to genocide, overshadowing the many centuries when Jews had lived in relative peace, and both their problems and their prospects had been of a different kind. In Molho’s bookshop, one of the few downtown reminders of earlier times, I found Joseph Nehama’s magisterial Histoire des de Salonique, and began to see what an extraordinary story it had been. The arrival of the Iberian Jews after their expulsion from Spain, Salonica’s emergence as a renowned centre of rabbinical learning, the disruption caused by the most famous False Messiah of the seventeenth century, Sabbetai Zevi, and the persistent faith of his followers who followed him even after his conversion to Islam, formed part of a fascinating and little-known history unparalleled in Europe. Enjoying the favour of the sultans, the Jews, as the Ottoman traveller Evliya Celebi noted, called the city ‘our Salonica’ – a place where, in addition to Turkish, Greek and Bulgarian, most of the inhabitants ‘know the Jewish tongue because day and night they are in contact with, and conduct business with Jews.’

Yet as I supplemented my knowledge of the Greek metropolis with books and articles on its Jewish past, and tried to reconcile what I knew of the home of Saint Dimitrios – ‘the Orthodox city’ – with the Sefardic ‘Mother of Israel’, it seemed to me that these two histories – the Greek and the Jewish – did not so much complement one another as pass each other by. I had noticed how seldom standard Greek accounts of the city referred to the Jews. An official tome from 1962 which had been published to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of its capture from the Turks, contained almost no mention of them at all; the subject had been regarded as taboo by the politicians masterminding the celebrations. This reticence reflected what the author Elias Petropoulos excoriated as ‘the ideology of the barbarian neo-Greek bourgeoisie’, for whom the city ‘has always been Greek’. But at the same time, most Jewish scholars were just as exclusive as their Greek counterparts: their imagined city was as empty of Christians as the other was of Jews.2

As for the Muslims, who had ruled Salonica from 1430 to 1912, they were more or less absent from both. Centuries of European antipathy to the Ottomans had left their mark. Their presence on the wrong side of the Dardanelles had for so long been seen as an accident, misfortune or tragedy that in an act of belated historical wishful thinking they had been expunged from the record of European history. Turkish scholars and writers, and professional Ottomanists had not done much to rectify things. It suited everyone, it seemed, to ignore the fact that there had once existed in this corner of Europe an Ottoman and an Islamic city atop the Greek and Jewish ones.

The strange thing is that memoirs often describe the place very differently from more scholarly or official accounts and depict a society of almost kaleidoscopic interaction. Leon Sciaky’s evocative Farewell to Salonica, the autobiography of a Jewish boy growing up under Abdul Hamid, begins with the sound of the muezzin’s cry at dusk. Albanian householders protected their Bulgarian grocer from the fury of the Ottoman gendarmerie, while well-to-do Muslim parents employed Christian wet-nurses for their children and Greek gardeners for their fruit trees. Outside the Yalman family home the well was used by ‘the Turks, Greeks, Bulgarians, Jews, Serbs, Vlachs, and Albanians of the neighbourhood.’ And in Nikos Kokantzis’s moving novella Gioconda, a Greek teenage boy falls in love with the Jewish girl next door in the midst of the Nazi occupation; at the moment of deportation, her parents trust him with their most precious belongings.3

Have scholars, then, simply been blinkered by nationalism and the narrowed sympathies of ethnic politics? Perhaps, but if so the fault is not theirs alone. The basic problem – common to historians and their public alike – has been the attribution of sharply opposing, even contradictory, meanings to the same key events. They have seen history as a zero-sum game, in which opportunities for some came through the sufferings of others, and one group’s loss was another’s gain: 1430 – when the Byzantine city fell to Sultan Murad II – was a catastrophe for the Christians but a triumph for the Turks. Nearly five centuries later, the Greek victory in 1912 reversed the equation. The Jews, having settled in the city at the invitation of the Ottoman sultans, identified their interests with those of the empire, something the Greeks found hard to forgive.

It follows that the real challenge is not merely to tell the story of this remarkable city as one of cultural and religious co-existence – in the early twenty-first century such long-forgotten stories are eagerly awaited and sought out – but to see the experiences of Christians, Jews and Muslims within the terms of a single encompassing historical narrative. National histories generally have clearly defined heroes and villains, but what would a history look like where these roles were blurred and confused? Can one shape an account of the city’s past which manages to reconcile the continuities in its shape and fabric with the radical discontinuities – the deportations, evictions, forced resettlements and genocide – which it has also experienced? Nearly a century ago, a local historian attempted this: at a time when Salonica’s ultimate fate was uncertain, the city struck him as a ‘museum of idioms, of disparate cultures and religions’. Since then what he called its ‘hybrid spirit’ has been severely battered by two world wars and everything they brought with them. I think it is worth trying again.4