Полная версия:

Not that Kinda Girl

Lisa Maxwell

Not that Kinda Girl

A Story of Secrets, Longing and Laughter

Dedication

For Paul and Beau

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction: Down at the Duke

1 Meet the Family

2 Early Days at the Elephant

3 Italia Conti Girls

4 My Secret Shame

5 First Love

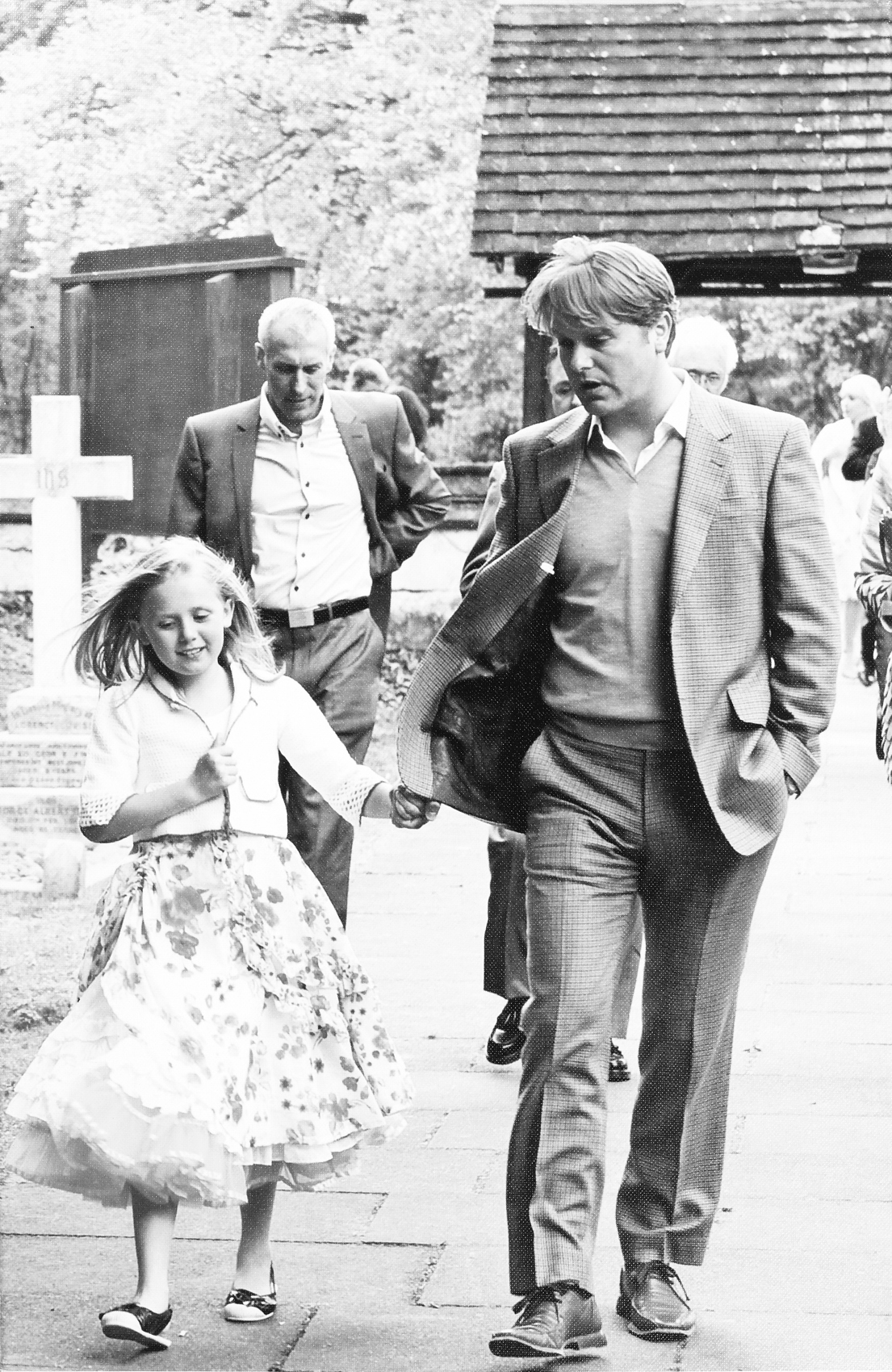

Photographic Insert I

6 Moving On

7 Down to the Wire

8 The Lisa Maxwell Show

9 Life in LA

10 Meltdown

11 Coming Home

12 Falling in Love

13 Beautiful Beau

Photographic Insert II

14 Being DI Sam Nixon

15 Running on Empty

16 As One Door Opens …

17 Father Unknown

18 Finally Me

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

Down at the Duke

As I walked towards the Duke of Sutherland in Walworth I could hear Nan’s voice belting out one of her favourite songs:

‘I’d like to be good …

And I know that I should …

I’m just not that kind of a girl …’

Just hearing her voice gave me a warm feeling. I’d always loved these words, because they’re funny and so familiar to me, from my earliest memories. As I pushed the heavy pub door open she was still at the piano, her left hand vamping a rhythm without moving across the keyboard, her right picking out the tune. She reached the last two lines:

‘Old Tommy Tucker …

Everyone knows he’s a dirty old … fella!’

The pub erupted in cheers and laughter, even though everyone there had heard the song before. I made my way through the fuggy, crowded bar, inhaling cigarette smoke and beer fumes, to the upholstered bench seat where Nan always sat with Grandad and their friends. She was basking in the applause and free drinks being sent across to their table.

‘Oh my Gawd, look who’s ’ere! Hide your wallet, Jim,’ she said when she spotted me.

‘I’m saying no, clear off out of here!’ Grandad would always say before I even had time to speak.

They were both laughing, and so were their friends.

I’d launch into my speech: ‘Guess what? I’ve seen these shoes in Grants in the Walworth Road, and they’ve only got one pair in my size. They were so nice, they said they’d put them by for me …’

As I wriggled myself in between them on the bench seat, I’d look at Nan.

‘You’d better speak to your grandad,’ she’d say, so I’d turn puppy-dog eyes on him.

‘Please, Grandad – they’re really nice,’ I’d tell him.

‘I bet they are,’ he’d say.

‘Please, Grandad, I won’t ask for anything else ever again!’

Huge guffaws from everyone round the table.

‘How much are they?’ he’d ask, already putting a hand in his pocket.

‘Only £14.99.’

‘Here’s fifteen nicker – clear off, that’s yer lot!’

I would skip out of the pub with the whole group smiling and watching me and, I imagine, thinking, ‘Aw, how could you resist her?’ Even though I was 16 I was tiny, slim and, because of my stage-school training, confident. I knew Nan and Grandad were proud of their little Lise whenever I went into the pub, they loved me – and I also knew, from an early age, that when Grandad had a few drinks inside him I could get anything out of him.

Nan, Grandad and Mum adored me. I lived with all three of them and I was the centre of their universes. I never went without anything; they spoiled me rotten. As far as Mum was concerned, nobody could ever point a finger at me and say I lacked anything. Except one big thing she was unable to give me: a father.

On my birth certificate there are two stark words, words branded on my soul: ‘Father Unknown’.

Today, with more than half of all babies born to unmarried couples according to the Office of National Statistics, the stigma of being illegitimate has pretty much gone. It’s a word you never hear now, and a good thing, too: it means illegal, beyond the law. That’s a terrible stamp to put on a child. I was born outside the law, and back then in the 1960s only 5 per cent of all babies did not have married parents.

My birth was something friends and family whispered about, hoping I wasn’t listening. A child born ‘out of wedlock’ was something to be ashamed of, the subject of gossip and innuendo: a stain on a family. This was something I was aware of from the very beginning. I always felt the love I was given was tainted with embarrassment and shame, a shame that has coloured my life in so many ways; it has affected my relationships, my work, everything. It’s a shadow that stretched long and deep and out of which I have only recently emerged into the sunshine.

Yes, I have always been bright and bubbly, funny, up for a laugh and a party, but the parties, the drinks and the laughter, everything was a way to keep on moving, to make sure I never stood still long enough to look deep inside myself. Finally, in the last few years, I have come off that merry-go-round and found a quiet, happy place in life where I can face up to myself and my story. I’ve come to terms with my birth; I know who I am. It’s been a long and at times difficult journey, but writing this book has also helped me find myself and lay to rest the ghosts that have haunted me.

CHAPTER 1

Meet the Family

I was only three years old, too small to see over the balcony outside our second-storey council flat at the Elephant and Castle, but there was a metal grille set into the brickwork that gave me a view of the estate below. While Nan tried to drag me back indoors, I was clinging to the bars, screaming and kicking hysterically. Below, I could see my mum getting into a minicab with a man in the back.

‘Your mother’s entitled to go out …’ Nan was saying as she struggled to contain my hysteria.

‘She’s with a man, she’s with a man!’ I was yelling.

‘Just get in the car, Val. She’ll be all right,’ Nan shouted to Mum as she finally prised me away and dragged me back inside.

Mum seemed to be in some sort of danger: the thought of her with a strange man was disturbing – I felt she couldn’t protect herself. And I hated her for leaving me to be with a man. This is my earliest memory. I can’t say exactly how I knew it was wrong; at that age you simply sense it from the way the grown-ups are trying to hide it. Mum didn’t say goodbye – she slipped out, secretively – and when I asked where she was, Nan and Grandad had exchanged sideways glances. So I panicked: I wanted her to come back. In some childish, unrealised way I wanted to save her from the terrible things about to happen to her.

Even then, too young to understand it properly, I had taken on board so much of the shame of being born out of wedlock and all the judgement that went with it that I felt my mum should be whiter than white and live like a nun. I had no idea how or why, but I knew a man had been involved in my arrival and this was something to be ashamed of, that it had been wrong. How did I develop such dark thoughts from such an early age, such fully formed moral opinions about her life? It was as though they seeped into me without anyone ever sitting me down and really spelling it all out. I don’t remember Nan and Grandad ever saying bad things about her, they were kinder than that, but the disapproval and half-heard gossip about my own mysterious ‘Father Unknown’ became part of me by osmosis.

I had picked up, probably from the whisperings of the grownups, that Mum had ruined her life by going with a man, and so I was terrified whenever I saw her with one. Men spelt trouble: disaster, shame, something dirty. So any attempt she had at a private life was thwarted, partly by the stigma of being an unmarried mother, but also – I’m ashamed to admit – by me, and from an early age I was determined to sabotage any chances she might have.

Mum never talked about it properly to me: the usual way of dealing with things in our family was to try and ignore them. She never said it was OK for her to have a boyfriend and she was entitled to some happiness and a loving relationship. All she ever said was that no one wanted her because of me. Imagine having that on your shoulders all your life. For her part, she felt she had to compensate, to make sure I missed out on nothing because I didn’t have a dad. I ruled the roost. From the day I was born I controlled her life. Obviously any baby and small child must be the first priority, but Mum lost herself completely the day I was born.

The Rockingham Estate at the Elephant and Castle was where I grew up, living with Mum, Nan and Grandad at 15 Stephenson House. The estate is a collection of red-brick, four-storey blocks of flats built in the 1950s, with scrubby, worn grass in between. To get to our flat we had to go up two flights of stairs and then walk along the balcony in front. We were round the corner of the building, the last stretch of balcony, so quite private.

It was a comfortable home and a good place to grow up. Nowadays estates like this are rough, with gangs and the associated drugs and violence, but when I was little the only ‘gang’ was the knot of kids I played with – endless games of ‘Penny Up’, ‘Cannon’ or ‘Run Outs’. We ebbed and flowed around the area between the flats, hiding and chasing each other all day through the school holidays until our mothers stood out on balconies calling us in for tea, which was what the evening meal was called (‘dinner’ was served at midday). Next to the estate was the strangely named Jail Park (I think it got its name because it was beside the Inner London Sessions court) and this, too, was a safe playground.

Mum has an old black-and-white photo of the Coronation party held on the estate in 1953. All the mums and teenagers stand in the background while 50 kids sit at a great long table, stuffing themselves with jelly and ice cream. It seems like a different era, an age when neighbours looked out for each other and everyone helped out, but it was only 10 years before I was born and the estate was still a friendly, caring place to grow up. At least, that’s how it seemed to me.

Because it was a council estate all the front doors were painted the same colour: red. To this day whenever I move into a new house the first thing I do is change the colour of the front door just because I can. The only bit that scared me was the stairwell: the stairs were made of concrete with sparkly bits in it – for some reason, you only see this in council flats of that age. Yellow tiles ran halfway up the walls. There was no graffiti and it didn’t smell like a public urinal but it was dark and grubby and made me nervous. I don’t know what I thought would happen but I used to run up those stairs as fast as I could, often shouting, ‘Come on, Billy, there’s a good Alsatian!’ to my protector, an imaginary dog.

Our flat had three bedrooms, a living room, kitchen and bathroom. When I was really small my Uncle Alan lived there too. But let’s go back to the very beginning. How did I come to be living with Nan and Grandad and sharing a room with Mum?

Let’s start with Nan and Grandad. They were such an important part of my life. A typical working-class couple, they were strong characters. Grandad drove a road sweeper for the council, which was a bit embarrassing because he parked this big yellow-and-black vehicle near our flats – I think he even went down the pub in it. He also did planting for the council in Battersea Park. He liked his work, and we had window boxes at home. Grandad won an award for the best window boxes on the estate – I’ve a feeling we were perhaps the only people there who had them.

Grandad’s shoes were always immaculate and he stored them in a little cabinet with all his kit for cleaning them. In cold weather he wore a flat cap. He had a tiny moustache, a bit like a Hitler moustache, like a bit of black tape stuck under his nose. For years I never had a clue what colour his hair was because it was Brylcreemed down. It was only when he was old that I could tell it was grey underneath. He rolled his own cigarettes with Golden Virginia tobacco, but Nan never smoked. Mum still has his toolbox with the nails and screws sorted and stored in old tobacco tins.

Nan and Grandad met when they were young, childhood sweethearts. He was the only man she’d ever been with. Her family was very poor, but his were a bit better off because his mother was a moneylender. In the old photos I’ve seen they look quite smart and Nan’s family seem really ragged in comparison. Grandad (Jim Maxwell) was a cheeky lad: his nickname was ‘Bagwash’ because there was a laundry round where he lived called ‘Maxwell Bagwash’. He saw this young girl (Rose) eating chips and said, ‘Give us a chip, Ginge’ – he called her ‘Ginge’ because there’s a bit of ginger colouring in her family, and as Nan grew older and greyer she always had her hair tinted a reddish colour. Alan was born ginger, and there were lots of jokes about how he must be the milkman’s, but it’s in the family. When they got married Grandad’s family felt he could have done better for himself, but he and Nan were together for the rest of their lives.

They both worked hard – Grandad was still working when he died at 76. Nan was always doing jobs and usually more than one: cleaning, working at the bookies. Their social life revolved around the pub. Nan was musical, and it’s fair to say she had a showing-off gene (in case you’re wondering where I get it from). She taught herself to play the piano by ear, never had a lesson, and would belt out songs like ‘Tommy Tucker’ and ‘Slap a Bit of Treacle on Your Pudding, Mary Ann’. She loved it, and that’s why she insisted Mum should look after me at weekends – nothing, not even me whom she idolised, could get in the way of their time down the pub. Nan loved having an audience in the palm of her hand. Everyone in the pub knew each other, knew all about their kids, there was a great sense of community.

I can still sing all her good old London songs. Nan was singing until she was in her eighties and perfected the same throaty wobble in her voice on a big note that Vera Lynn had. In April 2003, when I was the subject of This Is Your Life, she had Michael Aspel eating out of her hand and insisted on singing, finally getting her break on national television. As she got older and her voice wasn’t so strong, she would hold the mike too close (which gave a fuzzy edge to the sound), but my memories are of her belting the words out.

Nan was of average height (there’s nobody else in our family who is small like me) and the only make-up she ever wore was lipstick, which to be perfectly honest was never expertly applied. Let’s just say her lipstick thought her lips were bigger than they were. At home she wore a pink nylon overall, the sort of thing only Nans had.

So that’s Nan and Grandad, and now it’s Mum’s turn. Obviously I wasn’t around when all this happened, but eventually, years after my childhood, I heard it from her. It was not easy for Mum to tell her story, or to live it either: life on the estate may have been safer and friendlier in those days, but people were also a lot more judgemental and it was tough for a single mother. Her story has been shrouded in shame and half-truths for most of my life. In fact, it’s only in the past few years that I’ve managed to piece it all together.

My mum Val is the second eldest of Nan and Grandad’s four children: Shirley was four years older and after Mum came Jim and Alan. As a small child Shirley had TB, and at 18 months she went into hospital and only left when she was six. When she came home she thought Nan and Grandad were a nurse and a doctor; it was ages before she called them ‘Mum’ and ‘Dad’ again, and they were overjoyed when she did. This was at a time when families could only visit children in hospital for a couple of hours every day so it must have been very hard on them all. Val always felt Shirley was the favourite, and perhaps she was because of what she’d been through. Anyway, she was the one who could do no wrong and I think in a way both she and Mum fell into their roles: Shirley did everything right, while Val was the rebellious, cheeky one.

All Nan’s children attended the Joseph Lancaster school, which I went to later, which felt nice for me because I liked that feeling of continuity, of being part of the family, one of Nan’s children. Afterwards, they all attended the same grammar school: Walworth Central. Despite being the only member of her family to pass the 11-Plus, Mum left school at 15 and worked in office jobs. She was doing the wages at Arthur Miller & Co just off the Bermondsey Road (a firm which made donkey jackets) when she became pregnant with me at the age of 22. By then Auntie Shirley was married – she married early, her first serious boyfriend – and Uncle Jim was working in the Channel Islands, so only Mum and Alan were living at home.

Mum was very glamorous-looking – 5’8”. I’ve got a picture of her sitting like a model with her big peroxide-white hair back-combed up and wearing her winklepickers and a tight little cardigan. She looks so powerful, so in control of her life. Yet she didn’t handle anything difficult that happened to her in the way you’d imagine the woman in the photo would. It was the early sixties and in some ways women were beginning to take charge of their lives, but the moment they became pregnant it was right back to the fifties, the days when nice girls didn’t part their legs until they were married and any girl who got pregnant was ‘no better than she ought to be’.

Everyone who knew Mum when she was young says she was extremely attractive, great fun, very into how she looked and having boyfriends. Even now, when I say those things, I feel I have to add, ‘but not in a tarty way’. I think I just imbibed the general feeling in the household that my mother was a bad girl who liked boys a bit too much and ended up getting pregnant like girls who sleep around. That was the way of thinking of Nan and Grandad’s generation, the judgemental view I grew up with.

Mum used to go out with a friend, Norma, who worked as a receptionist at the same firm. One evening on the way home from work, Mum (who was 20 at the time) bought ‘Let’s Twist Again’ by Chubby Checker. After playing it back at the flat, she wanted to go out and have fun, so she rang Norma – I’ve a lot to thank Chubby Checker for! They went to a pub in Lambeth Walk and a couple of guys came in, one of them wearing what my mum described as a ‘Frank Sinatra’ hat.

‘He’s gorgeous, he reminds me of Paul Newman,’ Mum told Norma as soon as she clapped eyes on John Murphy. Luckily, Norma fancied the other one. Mum liked the self-assured look of John – she always went for the cocky ones. After the ritual chatting-up, Mum and Norma agreed to go on to a drinking club in the Strand. Being close to Fleet Street, it was a place mostly used by printers (John worked ‘in the print’ for a firm of typesetters in Shoe Lane). As Mum was to learn much later, he was married, but his job gave him great cover for their affair because everyone knew printers worked shifts so on the nights he wasn’t able to see her he had a perfect excuse.

Mum and Norma were bowled over by these two blokes, but Mum admits they were much keener than the men so they took to hanging around in the drinking club in the hope of seeing them. Sometimes John would ring Mum at work and she’d walk around on Cloud Nine for the rest of the day. She’d really fallen for him. She admits she always knew she was more into the relationship than he was, but that’s young love for you. And she’s often told me she was bang in love with him. She used to say, ‘You always kid yourself that they will get keener, don’t you?’ John would sometimes come to the flat and go to the pub, so Nan and Grandad met him too, but he never fully played the role of Mum’s boyfriend – he always had a mate with him.

It was an erratic affair: Mum could go weeks without seeing him, but she was always desperate for him to call, and whenever he did she would drop everything. She was mad keen and that’s why she says she slept with him: desperate to hang on to him, she was trying to take the relationship to another, more committed level. Some nights he would come round to Nan and Grandad’s at about 2 a.m. after he’d finished work and Mum would let him in. He’d stay for a few hours and creep out later. Two years into the relationship, however, Mum found she was pregnant and John Murphy was about to become ‘Father Unknown’.

I think she didn’t believe it could happen to her: she admits she was in denial. When she missed her first period she thought it must be because she had a cold, and the next time it had to be an upset stomach. When she faced up to it she started jumping down whole flights of stairs, drinking neat gin and taking hot baths, but I was determined to make my entrance – Mum says I was a ‘clinger’. You couldn’t have abortions in those days (they were illegal) and besides, she wouldn’t have known where to start.

At first the only person she told was her friend Norma. When she was sure, she told John Murphy, and that’s when he dropped the bombshell in her hour of need: ‘I can’t do anything, I’m married,’ he confessed. Mum says it never occurred to her that he might be married. She admits she should have questioned him more and should have known because he wouldn’t commit, but she never did: she just wanted him.

Mum was devastated, but told no one else, and because she was tall and slim she managed to conceal her bump for a long time. Eventually, when she was about six months pregnant, she broke down in floods of tears at work and confessed to one of the directors. He asked why she was so upset and she said, ‘Because I am not married.’

In that moment of utter despair he gave her the support she so badly needed. ‘A baby is a joyous event,’ he told her. ‘You have to embrace it.’ The owner of the company told Mum that they would do anything they could to help, so it’s unfair to say everyone was judgemental, but in reality no one could do much to help her.

For Mum, the biggest problem was that she had not told her parents. A daughter ‘in trouble’ was such a shameful thing and she was terrified of Grandad’s reaction. He was old school: he’d sit in his chair and call for Nan to pour him a cup of tea, even if the teapot was in front of him and even though Nan went out to work and probably needed a sit down, too. Some things were women’s work.

Somehow, Mum heard about a mother and baby home in Streatham and she got herself booked in there. But she didn’t like it when she went to see the people in charge: she sensed their disapproval and they made her feel there was a lot of shame involved in going there – which, of course, in those days there was. This is not the place to go into the conditions of homes for unmarried girls, but I don’t think many who went there in the fifties and sixties would describe them as happy, caring places. Mum was at her wit’s end and had no idea what else to do: she was supposed to move into the home six weeks before the birth, give the baby (me) up for adoption as soon as it was born and then stay for six weeks afterwards. She packed her bag and even wrote some letters, which she was going to send to Uncle Jim in Jersey for him to post one back to Nan and Grandad each week as if she was working out there.

‘I don’t think I ever said the word “adopted”, even to myself,’ she later told me. ‘I was in denial about what would happen to my baby. I didn’t think about it.’ I can hardly imagine how scared and alone she must have felt as she made these elaborate plans. In the end, it was clearly too much: Mum couldn’t keep it a secret from Nan any more and confessed she was pregnant. Nan was upset at the news but even more concerned about the idea of Mum going into the home and having to give the baby away. She told her not to go and said they would face Grandad together.