скачать книгу бесплатно

Yotkhee

Andre Martin

This book is just amazing! It’s captivating and full of adventures. Myths and legends, tales and songs will help as to study English, so to enrich the vocabulary and master the language.

Yotkhee

Andre Martin

Illustrator Julia Khruscheva

Translator and Teacher of English at Nizhny Novgorod State Linguistic University Olga Lukmanova

Proofreader Cynthia Tucker

Translator, teacher of English, School #1, Nadym, YaNAO, Russia Andrei Martinov

© Andre Martin, 2021

ISBN 978-5-0053-3856-3

Created with Ridero smart publishing system

A Tale within a Tale

Part I.

Yotkhee

Foreword

All peoples of Earth have their own myths and legends, their own fascinating cultures, customs, and traditions. In Russia alone (which is the largest country in the world) there are more than 195 peoples or ethnic groups, each with its own language.

Studying all these cultures and languages is always incredibly exciting. It’s like you find yourself in a totally different world or on another planet – because, of course, each ethnic group has its own music, songs, clothes, and ways of life that are different from yours.

In this tale-within-a-tale, the author has tried to show at least some of the most fascinating things about just one of Russia’s many wonderful peoples, hoping that his curious young readers would get excited about their planet’s many nations and ethnic groups, each with its own history, culture, literature, and language, and would become involved in learning more and more about all of this.

To see how very different things could be, take a look at the alphabet of the good people you’re going to read about. It even looks different, doesn’t it? It is very close to the Russian alphabet (which is called Cyrillic), but it’s different even from that, because it has letters for some sounds that do not exist in Russian or in other languages.

Besides, each culture has something that we all can admire and might even want to imitate or adopt. Which is probably the best way to learn anyway.

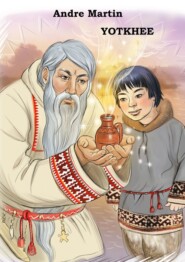

Colorful illustrations, made by the artist according to the author’s careful instructions, will help the readers to get a better visual picture and a clearer understanding of what he was trying to tell them.

Happy reading to you all!

«Keep up, Khadko,[1 - Khadko – a male name.] we have to get back to the camp before sundown!» called the father to his six-year-old son. He pulled their small flat-bottomed ngano[2 - Ngano (Nenets) – a flat-bottom boat.] out of the water, tied it to the stake driven into the bank, and began to carefully stack the fish they’d caught onto the khan[3 - Khan (Nen.) – a sledge.] – a large take of muksun,[4 - Muksun (Nen.) – a type of whitefish.] broad-nosed whitefish, and white salmon: the best that rivers and lakes of this Upper End of the World can yield to reindeer herders. He then sat down on the left side of the khan and grabbed the reins and the khorei,[5 - Khorei – a long pole for guiding a team of reindeer.] ready to go.

The boy was still on the bank, expertly skipping stones across the water. He didn’t want to leave and go back to the camp. It didn’t often happen that Dad took him fishing or hunting: he was still too young. The day was quiet, with no wind at all, and the orange-colored autumn sun was bright in the vast blue sky.

«You’ll make the spirit of the water angry,» his father called out, when he saw what the boy was doing. «You mustn’t throw anything into the river!»

«I mustn’t?» responded Khadko, more in surprise than wanting to know more, and dropped the remaining stones onto the ground.

«Come on, son, let’s go,» his father called again. «Ah, dinner will be great tonight,» he added with a satisfied smile when they finally got going. «Muksun is all large and fat this year.»

Khadko sat on the right side of the sledge, holding on tight to the edges, watching his father’s skillful movements. He was an observant child. The sledge was flying over the tundra, and the handsome, powerful reindeer, like huge fairytale birds, were carrying little Khadko back home, to the camp.

«Vydu’tana[6 - Vydu’tana (Nen.) – the chief shaman of the highest rank and of the Upper World, according to Nenets beliefs.] is here!» suddenly cried his father, half-rising for a moment when they darted out from behind another tall hill and could finally see their camp with its three teepees. He turned around to the boy, calling loudly again, «Vydu’tana is here, Khadko!»

The boy half-rose on the sledge too, peering into the distance and trying to make out the man his father was talking about.

«How does Dad know that someone has come?» he wondered. «We’re still so far away. I can’t see anyone!»

His father looked at him again, grinned, and artfully guiding the sledge, added in a loud voice:

«You can’t miss the large reindeer and the beautiful sledge of the tadebya![7 - Tadebya (Nen.) – a shaman.] Look at how the fur and the hides shine in the sun!»

And indeed, the gorgeous white and gold sledge would be hard to miss even at a distance. It was hand-carved, hand-painted, covered with snow-white deer hides, and pulled by a massive, strongly-built nyaravei[8 - Nyaravei (Nen.) – a white stag.] with huge white branching antlers, his sleek gilt harness glittering in the bright autumn sun.

Khadko’s father got up on the sledge and was now driving his team of strong, swift and obedient padvy[9 - Padvy (Nen.) – piebald reindeer.] standing up. He had to yell to make himself heard over the loud swishing of the air, but his voice sounded happy:

«You know, son, Vydu’tana only visits those who are kind and hard-working.»

The boy knitted his eyebrows slightly and looked pensive. He had once overheard old men talking about a wise teacher who lived on the top of a high mountain in the north of the Urals and sometimes rode around the tundra, stopping at people’s camps to tell children and grown-ups his wonderful stories.

As swift as a khalei[10 - Khalei (Nen.) – an arctic seagull.] diving for its catch, the sledge pulled up to the first tepee at the edge of the camp, made a sharp turn, and stopped almost instantly. Khadko quickly jumped off and ran over the mossy ground straight to the campfire already circled by children. No wonder! The great wise teacher had come to visit them!

Near the camp’s main tepee, a tall, sturdily-built man was talking to the reindeer herders. He was wearing a clean, white malitsa[11 - Malitsa (Nen.) – an outer hooded garment for winter made of buckskin.] which in the sunshine seemed to shimmer with all the colors of the rainbow. His long white beard was neatly tucked under a multicolored belt with gleaming bear and wolf fangs hanging from it. There was also a large, slightly curved knife with a horn handle, in a richly decorated sheath inlaid with small gemstones that gleamed and glowed in the evening sun. The guest’s malitsa and kisy[12 - Kisy (Nen.) – tall winter boots widely popular among the peoples of the Upper North (the Nenets, the Khanty, and the Mansi). They are made of hides taken off deer legs (called «kamus’) and have thick multiple-layer soles.] were covered with intricate, beautifully embroidered patterns, sparkling with even more gemstones of various shapes and sizes. The laces on the white kisy boots were woven out of several multicolored straps of leather, adorned on the ends with small wooden figurines of some unknown creatures.

In the Far North, days were already beginning to grow shorter. Summer was coming to its end, though winter was still a long way away. Ngherm[13 - Ngherm (Nen.) – a god of the Northern lands.] hadn’t yet unleashed his biting frosts and piercing icy winds on the camps, and it wasn’t yet time for Yamal Iri[14 - Yamal Iri (Nen.) – Grandfather Frost (Ded Moroz).] to get started on his journey.

In honor of their great guest, the herders made a huge bonfire and, after a festive dinner, everyone gathered around the fire, sitting on the sledges put together in a circle.

«It was a long time ago,» the white-haired old man finally said, starting his story. His chin rested on his right hand, his elbow on his knee. He was stroking his beard with his left hand and staring into the fire as if looking through and beyond the flames into some unknown depths.

«How long ago, Irike?»[15 - Irike (Nen.) – grandfather, grandpa. The Nenets believe it is impolite to address older people by name.] asked Khadko, rosy-cheeked and curious, his hair sticking out in funny tufts.

«A ve-e-ery long time ago, Son,» intoned the wise Vydu’tana gravely, shaking his head with a long sigh. «A very long time ago,» he repeated. «The great-grandfather of my great-grandfather’s great-grandfather used to tell this story,» he added. «Back when I was the same age as you are now,» he said, hiding his smile. The reindeer herders knew that the wise shaman was joking, and exchanged amused glances.

«Wow!» the boy shook his head in wonder. «So, how old are you now, then?» he asked.

The old man sat silent, still stroking his long white beard.

«Well, I was still very small when the wise teacher visited our camp,» said one of the khasava.[16 - Khasava (Nen.) – an adult man.] He was one of the men who helped Khadko’s father to move his herd of reindeer from camp to camp.

«I remember your visit as well,» another herder added from the other side of the bonfire.

The teacher lifted his grave eyes from the bright flames and slowly looked at each of the children who were patiently waiting for his story.

«You all need to know this,» he continued serenely, «so I will tell you all about it. Listen and try to remember everything well, so that you can tell the story to your great-grandchildren.» He was speaking slowly, in a deep, low voice, as if trying to make sure that everyone heard and understood his every word. «This way the good name of our people and their history will live on in the memory of our descendants.»

Suddenly his face lit up with a smile, and he looked at each of the little children in turn. Finally he started again.

«Our people came to this land from far, far away. The place where they came from had been very warm. They had never seen reindeer and didn’t know how to herd them. They had never worn such warm clothes,» the teacher pointed to the colorful, skillfully embroidered malitsas around the campfire. Then, stooping to his beautifully decorated belt, he took off it a small pouch, like a girl’s padko,[17 - Padko (Nen.) – a small embroidered bag for a girl.] made of fur and just as gorgeously adorned. He untied the string, took out a pinch of some dark sparkly powder, and threw it into the fire.

All at once, a tall pillar of blue and green flames shot high into the air. Startled, the herders shrank back from the fire, covering their faces and blinking at the dazzling light. However, the strange fire didn’t seem to burn them: it only lit everything around even brighter. The colorful blazes danced over the people’s heads like a river rolling and whirling in a strong wind.

Both the grown-ups and the children gasped with amazement. The herders’ eyes grew wide with wonder, and little Khadko’s mouth fell open. The tops of the flames reached high into the starry night sky, setting it on fire with a radiance almost too marvelous to behold. The light spilled wider and wider, blossoming into new colors and hues as it grew larger.

In a few moments, the flames gradually settled down, grew a little smaller, and suddenly turned into a stunning living picture, so real you could almost touch it. It showed them the wonderful place the teacher was talking about.

«Can we go there now?» asked Khadko eagerly.

Vydu’tana looked at the boy with a kind smile and answered:

«It would take more than a lifetime to go there and come back again.»

«What if we take the reindeer, Irike?» Khadko persisted.

«Even with the reindeer it would take a long, long time. Listen to my story, and then you will see how it is, alright?»

The tufted-haired boy nodded and, resting his head on his fists, prepared to listen.

«In that faraway place there are mountains, tall and beautiful, with their peaks piercing the clouds. On their slopes there are big leafy trees with strong, massive branches. Many different animals haunt the mountain paths, and many happy streams of living water run down between the rocks and boulders. In the valleys there are lakes with clear blue water, large and small. Butterflies flit from one lovely flower to another, and bees keep buzzing, going about their work gathering sweet and fragrant honey. The bright sun keeps that land warm and fruitful.»

«Why did we have to leave it, then?» Khadko blurted out.

Vydu’tana stopped, and Khadko’s father, who was sitting next to his son, whispered in his ear quietly:

«You shouldn’t interrupt when someone is talking, especially someone older. It’s bad manners.»

«I am sorry, Irike,» the boy whispered to the teacher at once, just as quietly. «It’s just that I’ve never heard such interesting tales before.»

«And it’s just the beginning,» the old man said mildly. «You will wonder at many more things before I am done talking.»

Khadko fidgeted a little on his sledge, trying to find a more comfortable seat, and finally settled down.

«We lived in that land for a long time and very happily. Winters there weren’t as cold as here, and they were short, although just as snowy.»

Yotkhee[18 - Yotkhee – «The Keeper of Wisdom,» vydu’tana’s other name. The Nenets do not call each other by real names, it is prohibited.] kept speaking, and the enormous deep screen which hovered, cloud-like, over the listeners’ heads, kept changing its multicolored pictures. The herders heard the chirping of unfamiliar-looking birds, the rustling of leaves, the babbling of streams, the cries of various animals, and the rushing of the warm wind in the tall grass – everything amazingly bright and beautiful.

«At first our families were small and close-knit. There was enough land for everyone. There was enough food for everyone. We enjoyed life, gladly welcomed every new day and every new guest who came to visit. We went to visit others as well. We exchanged gifts. We helped to heal the sick and to take care of children. We never cultivated the land or planted anything specially: everything we needed simply grew around our huts which we made out of young trees, weaving broad palm leaves around them to make walls for protection from winds and rains.»

As wise old Yotkhee continued with his story, sweet music started coming from the bright vision over his listeners’ heads: in the picture a small boy of seven or so was playing a soft tune on his reed pipe. He was standing on the low bank of a small blue river, and behind him there was a thick green forest where many paths were winding their different ways around the trees, big and small. Next to the boy the herders saw a little girl of about six, with a puppy in her lap. A doe with her fawn came out from behind the thick bushes on the opposite bank and stopped at the water, lifting its front left leg slightly and perking up its ears to listen to the song. Several noble-looking swans delicately glided onto the water, gently spreading their wings and bowing their long necks graciously as if to greet the young musician.

«This is me,» said the teacher, nodding his white head at the boy. «I got the reed pipe from my grandfather, our old shaman. He could see the future.»

Here the old man furtively brushed away a tear and kept looking at the picture intently until it disappeared, giving way to something else.

«Aw!» the herders gasped in admiration, some covering their mouths with their hands as their eyes grew bigger and bigger.

«Then you must be really old, Irike!» little Khadko couldn’t contain himself. «You have lived so many winters and summers that I couldn’t even count them on my fingers!»

The wise old man smiled and said:

«I will teach you how to live a long and healthy life – and how to stay strong even in your old age. But for now, just keep listening to my story.»

The herders couldn’t take their eyes off the beautiful pictures, which slowly kept changing one into another to the accompaniment of the sweet, restful music.

«With every year our families grew larger and larger, as did the families of our neighbors, so we had to think of what to do next: now there were more of us while the land and its plants stayed the same.»

Here Yotkhee paused and looked down at the fire as if remembering something that was important or moved his spirit. In a few moments, he continued:

«One day our old and wise shaman gathered together the council of elders and announced…»

The picture changed again and now showed people sitting inside a large teepee. All of them were elderly, with long white beards, but one clearly stood out. Dressed as a shaman, he was holding a tambourine and a drum stick and was addressing the rest of them in a grave tone:

«A great misfortune is coming our way,» he said. «Behind our Big Stones[19 - Big Stones (Nen.) – mountains. Ngarka Peh (Nen.) – a large rock. This is what the Nenets used to call mountains.] there are other tribes who have also grown too numerous for their old place. They want to find and settle on new lands, and they will come here too. But this place is already too small, even for us. Their coming will sow discord and strife. Some people will want to kill others. Many will die. But as Num the Wise[20 - Num – the Great Creator, the high god of the Nenets people.] has told us, we must not kill, for it is a great sin. However this is not even the worst that awaits us.»

At that moment everyone who wasn’t already looking at the old shaman lifted their eyes and stared at him in bewilderment. They knew well that he could see the future. The shaman continued.

«The Great Water is coming. The Master of the Eternal Birch-Tree with seven trunks[21 - According to Nenets legends, the Master of the sacred seven-trunk birch-tree, Khebidya Kho Erv, lives in the hollow of that tree. Once in every several thousand years, he comes out from the hollow, lifts up the birch-tree, and big waters come from under its roots, covering the land. With this water Khebidya Kho Erv washes away all sickness from the earth.] will lift its roots, and from under it there will rush out a big great flood which will wash away all the sickness from our land. Many families will perish in that flood. The Great Water will remain for seven suns and seven moons. Then, gradually, it will go away, and life will be restored again.»

«You know that even the Great Creator cannot stop the Master of the Birch-Tree. I am too old for long journeys and would like to stay here. But thankfully, our good gods have provided my family with an heir to whom I can pass all my knowledge and skills. He will take you to the new land where the Great Water cannot reach you. The journey will be very long and very hard, but there, in the new land, you will all be safe.»

Having said all this, the shaman raised his right arm bent at the elbow with his palm open towards the others. It meant, «I have spoken.»

The elders were silent, lowering their eyes and staring into the center of the circle. They were clearly shaken and saddened by the old shaman’s words.

In a few seconds, a gray-haired man on the opposite side of the tepee raised his hand, asking for permission to speak. Everyone nodded slightly, letting him know they were ready to hear what he had to say.

«Those are grievously sad words we heard from you today, O Great and Wise Healer,» the old man said. «We are ready to do your will and to save our people. We will make the long journey you’ve told us about. But tell us, who is this heir of yours? Who will lead us into the new land?»

Everyone looked at the wise shaman, and he spoke in a placid and confident voice:

«I speak of our young Yotkhee. The good spirits have given him so much strength and power that he will be able to do all that is needed. He will become a great healer. He also knows how to see the future and will give you good counsel. His spirit is strong, and his courage is great. He is an old soul, earnest beyond his years, and his memory never loses anything.»

A hum of approval ran through the elders’ circle, and they nodded in agreement. They knew well that the boy Yotkhee, vydu’tana’s grandson, indeed had wonderful powers: even at seven years of age he could heal the sick and give wise counsel, and sometimes he came up with really good ideas. Animals seemed to understand and obey him, often without words. The boy was kind and diligent, which meant that the good spirits would never leave him in trouble. And if he led the people, they would definitely be able to overcome all obstacles, handle all difficulties, and reach the new land where they would be able to live in peace and harmony with nature again.

The old shaman raised his open palm again and added:

«While we’re still here, I will teach little Yotkhee everything I know. I will teach him to speak to the gods. I will teach him how to live a long life without sickness, how to grow old and to remain strong at the same time.»

«Come here, Yotkhee, my son,» the old shaman called out to the boy the next morning, just as his grandson came out of the teepee yawning and stretching. The old man was already sitting cross-legged near the little fire he had made at dawn. He had been waiting for the son of his oldest son to wake up and climb out of the teepee so that he could catch the power of the first rays of heaven’s Great Light.

«Last night the Council of Elders decided that we must depart on a great journey,» the old shaman said. The boy was sitting next to him and listening with his whole being, his eyes looking straight into the shaman’s eyes.

«Great troubles are coming. To save our people, we must lead them towards the Land of the Dead. Our way will be long: a whole generation may be born, grow up, and depart to the Other World before you reach your destination.»

As the shaman was speaking, he kept looking into Yotkhee’s eyes, trying to discern whether there was any fear or doubt there and thus see if he should even continue. But the boy’s face showed nothing of what the old man was anxious about. When the shaman paused, the boy understood that it was a signal for him to respond.

«That’s what I thought too, O Wise Healer. The other day I had a beautiful dream, and in the dream the good spirits were calling us away to some distant place.»