Полная версия:

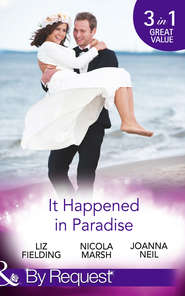

It Happened In Paradise: Wedded in a Whirlwind / Deserted Island, Dreamy Ex! / His Bride in Paradise

It Happened in Paradise

Wedded in a Whirlwind

Liz Fielding

Deserted Island, Dreamy Ex

Nicola Marsh

His Bride in Paradise

Joanna Neil

www.millsandboon.co.uk

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Wedded in a Whirlwind

Excerpt

About the Author

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Deserted Island, Dreamy Ex

Praise for Nicola Marsh

About Nicola Marsh

Dedication

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

EPILOGUE

His Bride in Paradise

Dear Reader

Praise for Joanna Neil:

About the Author

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

Copyright

‘Let me go!’ she demanded. ‘I don’t need you to get me out of here.’ And she continued to kick and writhe until she connected solidly with his shin.

It was enough. The girl was slender, but she had a kick like a mule, and he rolled over, pinning her to the ground.

‘Be still,’ he warned, abandoning reassurance, making it an order. He’d have to let go to slap her, and while the temptation was almost overwhelming—he was still feeling that kick—he chose the only other alternative left open to him and kissed her.

It was brutal, but effective, cutting off the stream of invective, cutting off her breath, and, taken by surprise, she went rigid beneath him. And then, just as swiftly, she was clinging to him, her mouth hot and eager as she pressed against him, desperate for the warmth of a human body. For comfort in the darkness. A no-holds-barred kiss. Pure, honest, raw need that tapped into something deep inside him.

As suddenly as it had begun it was over. Miranda slumped back against the cracked and now sloping floor of the temple.

‘Don’t! Don’t ever do that again!’

‘I could just as easily have slapped you,’ he said.

In truth they were both breathing rather more heavily, and her verbal rejection was certainly not being followed up by her body. Or his. Being this close to a woman who was no more than curves that fitted his body like a glove, soft skin, a scent in the darkness, was doing something to his head.

LIZ FIELDING was born with itchy feet. She made it to Zambia before her twenty-first birthday and, gathering her own special hero and a couple of children on the way, lived in Botswana, Kenya and Bahrain— with pauses for sightseeing pretty much everywhere in between. She finally came to a full stop in a tiny Welsh village cradled by misty hills, and these days mostly leaves her pen to do the travelling. When she’s not sorting out the lives and loves of her characters, she potters in the garden, reads her favourite authors and spends a lot of time wondering ‘What if…?’ For news of upcoming books—and to sign up for her occasional newsletter—visit Liz’s website at www.lizfielding.com.

CHAPTER ONE

MIRANDA GRENVILLE stood through the double baptism, holding each baby in turn as she made the promises, heard the vicar name names…

Minette Daisy…

Jude Michael…

Stood with each glowing mother—first her sister-in-law, Belle, and then Belle’s sister, Daisy—smiling as everyone took photographs. Even took some herself.

It was, without doubt, the most joyous occasion and her smile never faltered despite the turmoil of feelings that, inside, were tearing her apart.

Keeping her emotions hidden had been a hard-learned lesson, far more difficult than anything that came out of books; books were easy. But when, finally, the pain had become so great that hiding it had become essential for survival she had found the strength from somewhere.

It hadn’t always been like that.

There had been a time when she had let everything show, let her emotional need hang out for all the world to see. It had been a slow and painful lesson—one she’d learned from watching Ivo, her brother. She’d thought he was immune, but the power of a love that was beyond her comprehension, the joy of fatherhood, had shattered the ice cage that once held her brother a fellow prisoner in emotional stasis. Now she was isolated, bound and shackled by the one secret she had never shared with a living soul—not even with Ivo.

And so she smiled for him on this joyous day. Not that he was fooled. He knew her too well for that. Recognised her smile for the brittle thing that it was, sensing a fragility beneath the controlled veneer.

To see his puzzled watchfulness, his anxiety for her, clouding his eyes on what should have been the happiest of days made her feel like the spectre at the feast. She had to get away before he sought her out and asked the question she could see in his eyes.

Is there something I can do?

The answer was—had to be—no. He had already done more than enough. He’d been there with the tough as well as the tender love. He had been her lifeline, keeping her afloat, even when she’d come close to dragging him under with her.

He had a new life now and it was time to cut the ties, set him free of all that chained him to a painful past. She had to convince him that she didn’t need him any more, so she smiled until her face ached, toasted the babies, snapped pictures on her cellphone, tasted a crumb of each christening cake.

She was on the point of breaking when her sister-in-law announced that Minette needing feeding and she seized her chance.

‘Belle, I have to go,’ she said, following her into the nursery.

‘So soon?’ Belle took her hand, not to detain her, but in a gesture that was utterly natural to her, full of warmth, a kindness she knew she didn’t deserve. She had bitterly resented the glamorous Belle Davenport’s intrusion into her brother’s life. She’d hated her for being the kind of woman who drew people to her, hated her because Ivo couldn’t live without her, and she’d gone out of her way to make her feel like an outsider in her own home. Drive her away.

Stupid.

She, of all people, should have known that, once given, Ivo’s love was unshakeable.

‘I’ve got a plane to catch,’ she said, moving away. She didn’t want or need kindness. Didn’t deserve it. ‘It’s been a hectic few months researching the documentary on adoption and I thought I’d take the opportunity to grab some time for myself before we start filming.’

While Belle and Daisy were taking maternity leave from the television production company the three of them ran as a team.

‘What bliss,’ Belle said. ‘Anywhere interesting?’

‘Somewhere without a telephone,’ she replied. The caustic edge to her voice had become as natural as breathing. Actually it wasn’t such a bad idea. Then, as Minette searched hungrily for her mother’s breast and began to suckle, the sharp, woman-of-the-world act buckled and she had to look away. ‘Tell Ivo for me, will you?’ she asked through a throat that was thickening dangerously. ‘And Daisy.’

‘You’re not going to say goodbye?’

‘It’s better if I just slip away.’ She managed a shrug. ‘You know what Ivo’s like.’ He’d see right through her. ‘He’ll want to know where I’m going. Make me promise to keep in touch.’

A promise she couldn’t keep.

She needed to get away completely. Give him space to enjoy his new family. Escape from an excess of consideration, warmth, kindness and go somewhere where no one knew her. Where she could stop smiling, be angry, be herself…

About to say something, her sister-in-law changed her mind, instead squeezing her hand. ‘Thank you, Manda.’

‘What for? I promise you’re going to regret inviting me to be Minette’s godmother. I plan to set both my godchildren a thoroughly bad example.’

Belle shook her head, not taking her in the least bit seriously. ‘Not just for being Minette’s godmother, but for being so brilliant with Daisy, giving her a job, a purpose when she most needed it.’

‘I wouldn’t have kept her on if she hadn’t proved her worth,’ she lied.

She’d taken on Belle’s damaged little sister for her brother’s sake, her attempt to atone a little for the hurt she’d caused him, make amends, but in truth she understood Daisy in ways that Belle never could. She’d been in the same dark places, knew what worked and what didn’t, had known how to be tough when Belle had been emotionally racked.

‘Just warn Daisy from me that if she has any idea of becoming a stay-at-home mother she’d better think again,’ she said, sidestepping the soft-centred mush. ‘I’ve spent too much time training her in my little ways to let her off the hook.’

‘And thank you for not making a fuss when Ivo sold the house,’ Belle continued, refusing to be distracted from saying exactly what was on her mind. ‘I know how hard that must have been for you.’

Hard…

The Belgravia mansion that had been in her family for generations—a backdrop for the financial and political dinners, receptions, she’d arranged for her brother—had been her whole life when she didn’t have a life and she’d lavished all she had in the way of love on its care.

Belle, who’d hated the house from the minute she’d stepped over the threshold, hadn’t the faintest idea how hard it had been to let it go, but still, with a throat that ached and a heart like lead, Manda held her smile.

‘It would be a bit big for one.’ Then, ‘I’ve got to go.’

‘Manda…’

‘Now,’ she said, turning away and heading for the door before Belle did something stupid, like hug her. Before the tears stinging her eyelids spilled over and the ice cool image, the touch-me-not façade she’d built so carefully over the last few years cracked and she made a total fool of herself.

Nick Jago slid on to a stool and the barman, a leathery Australian whose yacht had been wrecked off the coast of Cordillera ten years earlier and had never found the energy to move on, poured him a small cup of thick black coffee and pushed it across the counter.

‘It’s a while since you were in town,’ he said.

‘I just came in to pick up my mail. There isn’t much else to tempt me into what passes for civilisation around here.’

‘Maybe not, but stuck out there by yourself you tend to miss the news.’ He produced a month-old copy of an English newspaper from beneath the counter. ‘I hung on to this for you.’

Jago glanced at the headlines of a tabloid that had the nerve to call itself a newspaper. Another politician caught with his pants down. Another family torn apart.

‘No, thanks, Rob,’ he said. ‘I’m not that desperate for something to read.’

‘Not that,’ he replied dismissively. ‘Inside. There’s a picture that I think’ll interest you.’

‘And you can keep your page three girls. Fliss will be back soon and I’d rather wait for the real thing.’

‘You sure about that?’

He shrugged. He was sure of nothing but death, taxes, and that her goodbye had been accompanied by a hot, lingering kiss that had been better than any promise. But Rob clearly knew something he didn’t.

‘Why do I have the feeling you’re about to disillusion me?’

‘I hate to be the bearer of bad news, mate,’ Rob replied, ‘but I have to tell you that your Fliss might have other things on her mind.’ He opened the paper at a double page spread. ‘“Sex, Slavery and Sacrifice… Exclusive excerpts from the sensational diaries of beautiful archaeologist Fliss Grant…”’, he read out loud.

Jago, his cup halfway to his mouth, slowly returned it to its saucer.

Archaeologist?

She’d been a postgrad student when she’d turned up at his dig. A volunteer, working for food and experience. There were a hundred more like her—well, maybe not exactly like her—but he wouldn’t have paid her, no matter how hot her kisses.

Rob, under the mistaken impression that he wanted to hear more, continued.

‘“Discover the secrets of Cordillera’s long lost Temple of Fire. Win a holiday on this exotic island paradise and see for yourself the ancient sacrificial stone—”’

‘What?’

Jago grabbed the paper.

One look at the photograph of the sexy blonde, one look at her khaki shirt, held together only by a knot beneath generous breasts and exposing a lot more flesh than the average archaeological assistant would sensibly display on a hard day at a dig, was enough.

Not that Fliss Grant was average in any way.

He hadn’t heard from her since she’d left the island at the end of the digging season when the rains had set in, but then he hadn’t expected to. There was no mobile phone signal up in the hills.

He hadn’t been bothered—honesty compelled him to admit that conversation had never been the attraction—and he’d had plenty of other things to keep him occupied.

As for the Cordilleran postal service—well, even if she had been moved to write, it was something of a hit-or-miss affair. It was why, when she’d offered to deliver copies of disks containing his diaries and photographs to his publisher, he’d handed them over without a second thought.

He stared at the photograph.

The very brief shorts, a slick sheen of sweat, the wet-look lips and provocative pose had been used to set the tone for diaries written ‘… by this dauntless female “Indiana Jones” who braved spiders, scorpions and deadly snakes to uncover the secrets of the island’s mysterious past…’

There was a photograph of a large hairy spider to ram the message home.

‘I knew the temples were there…’—She knew!—‘…and I was determined to prove it. Now you can read for yourself what I had to endure to discover the terrible truth behind the sacrificial stone…’

‘Give me strength,’ he muttered as he attempted to get his head around what he was seeing. And then, when he did, something painful squeezed at his chest and his mouth dried. She hadn’t simply taken the chance to make a heap of money using his diaries, his work.

He could have understood the temptation and, wrapped in her hot thighs, he might even have forgiven her. But there was another smaller photograph of Fliss and Felipe Dominez, Cordillera’s playboy Minister of Tourism, snapped as they’d left one of London’s fashionable nightclubs. She was wearing a dress that left little to the imagination and they were exchanging the kind of intimate look shared only by two people who knew one another very well.

So the only question left unanswered was when had Dominez and Fliss met?

Had it been by chance on one of her little excursions into town for supplies? Had Dominez sought her out and made her an offer she couldn’t possibly refuse?

Or had he been set up from the very start?

It wasn’t that unusual for postgraduate archaeology students to turn up out of the blue, having paid their own way to the site. They needed field experience to boost their CVs and he needed all the help he could get. The fact that Fliss Grant had a mouth, a body, as hot as sin that she’d been willing and eager to share with him had just made having her around that much more pleasurable.

No, he decided. This hadn’t been chance. The speed with which she’d achieved publication suggested that it was the culmination of a well thought out and efficiently executed plan.

Fliss Grant, it seemed, had ‘endured’ and ‘endured’ in order to get her hands on his diaries, his notes, his photographs and why would he be surprised by that? Women, as he was well aware, would endure anything to get what they wanted.

Not that she’d actually used any direct quotes, but then why would she bother? This publishing venture had nothing to do with dry scholarship.

He had no doubt that some hack, paid by Dominez, had ghosted this fairy tale from the bones of his excavation diaries, just as someone had been paid to make sketches from his photographs, producing an impression of the temple complex peopled with priests and sacrificial figures that had more in common with a fifties Hollywood epic than reality.

Not that he’d been credited in any way.

From this account, anyone would think Fliss had excavated the temple single-handed, enough to warn anyone with an atom of common sense that this was all hokum. But then this was straight out of the ‘God was an astronaut’ school of archaeology.

As he scanned the prurient accounts of priestly rites, he knew he should be grateful that his name had been omitted from this tabloid version of the temple’s history with its sexed-up versions of the images carved into the stone walls. The ‘naked virgins’, ‘bloody sacrifice’ scenarios, the sexual innuendo, were not something he’d want his name attached to.

But somehow, at that moment, gratitude of any kind was beyond him. This rubbish would reduce him to a laughing stock within the academic archaeological world and, without a word, he reached for the bottle of local brandy that Rob pushed in his direction.

It was unbelievably hot. No temple, no matter how ancient, was worth this kind of suffering, Manda decided, wiping the back of her arm across her forehead to mop up the sweat.

‘Come along, keep up,’ the guide called, with an imperious gesture. ‘There’s a lot more to see.’

He was evidently new to the job and hadn’t quite got the customer service thing nailed.

Since rebellion in the ranks was apparently unthinkable, he didn’t wait to ensure that he was obeyed but plunged further along the path in the direction of yet more ruins, his charges meekly trailing after him. Well, most of them.

Manda was not meek. Far from it. And she’d already had enough of this particular ancient civilisation to last her a lifetime.

Refusing to move another yard, she sank on to a huge fallen chunk of dressed stone that someone, long ago, had started to chisel into a representation of some beast. He’d evidently given up halfway through his task and if it had been a day like this, he had her sympathy.

She leaned forward, unfastening another button of a limp linen shirt that had not been designed for this kind of sweaty exertion, flapping the two edges to encourage what air there was to circulate and cool her damp skin.

Next time she grabbed the first flight on offer to the Far East, she’d take more notice of where she was going. Cordillera, she’d been assured when she’d called the booking agency, was going to be the next ‘big’ destination. She had caught part of a chat show interview with some impossibly glamorous female archaeologist who’d written a book about how she’d personally—and apparently entirely unaided—uncovered some ancient civilisation on the island, so maybe it was true.

Not really her thing; she’d been more interested in promises of unspoiled palm-fringed coves and white sand. Unspoiled was a euphemism for a lack of amenities, she discovered. They were trying, but the ‘resort’ at which she was staying was, so far, little more than a construction site.

Normally one look would have been enough. She’d have turned right around and caught the next plane out of there, flown on to somewhere where luxury was guaranteed.

But she’d cut and run from feelings she couldn’t handle, had told herself she didn’t care where she was going and, having stuck the equivalent of a metaphorical pin in the map, fate had brought her here.

Maybe this was fate’s idea of a joke but it had fulfilled a major part of her desire to be out of contact and its awfulness had, somehow, seemed exactly right.

But the lack of facilities, and an airport blockbuster that hadn’t lived up to its blurb, had left her bored enough to break the habit of a lifetime and allow herself to be persuaded by a representative from the tourist office, eager to promote the island, that it was something of a privilege to be one of the first outsiders to see the ruins. A real adventure. Something she’d tell all her friends about when she got home.

She hadn’t been totally convinced but at the time anything had seemed better than sitting alone with nothing but her thoughts for company.

Big mistake, she thought, pushing back damp strands of hair that were sticking to her forehead and pulling a face. Unfortunately, thirty miles inland, halfway up the side of a mountain on a route march around the seemingly endless maze of what they had been assured were the ancient temples and palaces, it was too late to change her mind.

Jago had been sitting on the altar stone for what felt like hours still holding the bottle of local brandy that Rob had slid across the bar, muttering, ‘On the house, mate…’

One more season was all he’d needed and then, come the next rains, he’d have returned to London and published his findings in the academic journals. Written a book that would never have made the bestseller list. There was nothing here sensational enough for that. No treasure. No startling revelations.

He wasn’t interested in sensationalism, bestseller lists, anything that would expose him to the glare of celebrity. If he’d wanted them, they could have been his for the asking any time in the last fifteen years.

All he’d wanted was to drop out of sight and lose himself in the work he loved.

He looked down at the bottle in his hand and finally broke the seal.

* * *

For a while Manda remained where she was, perched on her stone, quite content to wait until the rest of her party returned, idly tracing the outline of the half-finished figure with the tip of her finger. It was the head of a bird, she realised, a hawk of some kind, and she glanced up at a sky almost crowded out by the thick canopy of the forest.

When their pitiful little band of tourists—a couple of dozen people who were staying at the same complex, boosted by a group of captive businessmen whose plane had been delayed—had walked up from a clearing where they’d left the bus, she’d noticed a hawk, its wings outstretched and seemingly motionless as it rode the currents of air, quartering the side of the valley in search of prey.

She searched the small patch of sky that was now streaked with pink, but the bird had gone and the forest was wonderfully peaceful. She could no longer hear the tour guide’s sing-song voice pointing out the details they were expected to admire enthusiastically when, in truth, all they’d wanted was to be back at the coast with a very cold drink within easy reach.