Полная версия:

Trouble in Paradise: Uncovering the Dark Secrets of Britain’s Most Remote Island

TROUBLE IN

PARADISE

Uncovering the Dark Secrets of Britain’s Most Remote Island

KATHY MARKS

Dedication

For my parents

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Cast of characters

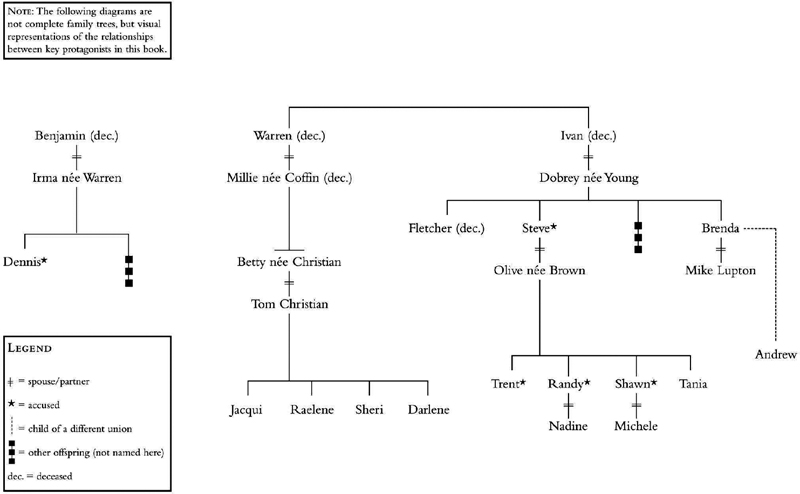

Christian clan

Brown family

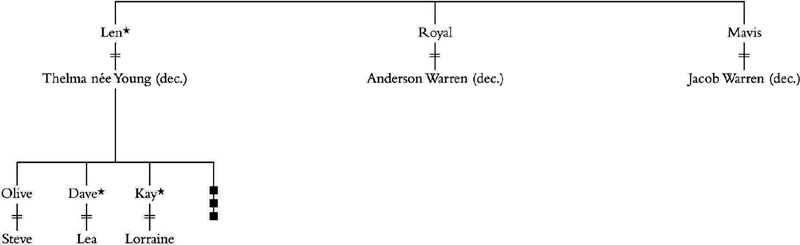

Warren clan

Young family

Prologue

Part 1—On the island

1 A surreal little universe in the middle of nowhere

2 Mutiny, murder and myth-making

3 Opening a right can of worms

4 No amnesty

5 The fiefdom and its leader

6 The propaganda campaign starts

7 Key witnesses evaporate

8 The trials begin

9 Let’s make-believe

10 Judgement day

11 ‘You can’t blame men for being men’

Part 2—Viewing Pitcairn from a distance

12 How the myth was forged

13 Politics, poison and power plays

14 Britain’s ‘ineffective long-range benevolence’

15 ‘I just did my job and minded my own business’

16 Interdependence + silence = collusion

17 Making legal history

18 The final trials

19 Reaping a sad legacy since Bounty times

20 Lord of the Flies?

21 The last throw of the dice

Epilogue—Isobel’s story

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

Cast of characters

Historical figures

Edward Christian (Fletcher’s brother)

Edward Young (mutineer)

Fletcher Christian (mutineer)

Harry Christian (hanged in 1898 for murder of wife and baby)

John Adams (mutineer and community leader)

Maimiti (Fletcher Christian’s Tahitian ‘wife’)

Matthew Quintal (mutineer)

Peter Heywood (mutineer court-martialled then pardoned)

William Bligh (captain of Bounty)

William McCoy (mutineer)

Media

Claire Harvey (The Australian; The Times)

Ewart Barnsley (Television New Zealand)

Kathy Marks (The Independent; New Zealand Herald)

Neil Tweedie (The Daily Telegraph; Press Association)

Sue Ingram (Radio New Zealand)

Zane Willis (TVNZ)

Officials and diplomats

Baroness Patricia Scotland (Former Overseas Territories Minister)

George Fergusson (Governor at time of writing)

Grant Pritchard (former Governor’s Representative)

Harry Maude (British colonial official in 1940s)

Jenny Lock (former Governor’s Representative)

Karen Wolstenholme (former Deputy Governor)

Leon Salt (former Commissioner)

Leslie Jaques (Commissioner at time of writing)

Martin Williams (former Governor)

Matthew Forbes (former Deputy Governor)

Richard Fell (former Governor)

Police and legal personnel

Adrian Cook QC (defence)

Allan Roberts (defence)

Charles Blackie (Chief Justice)

Charles Cato (defence)

Christine Gordon (prosecution)

Christopher Harder (former barrister)

Dennis McGookin (Kent Police)

Fletcher Pilditch (prosecution)

Gail Cox (Kent Police)

Graham Ford (court registrar)

Grant Illingworth QC (defence)

Gray Cameron (magistrate)

Jane Lovell-Smith (judge)

Karen Vaughan (New Zealand Police)

Kieran Raftery (prosecution)

Lord Hoffman (Privy Council)

Max Davidson (Kent Police)

Paul Dacre (defence)

Peter George (Kent Police)

Robert Vinson (Kent Police)

Russell Johnson (judge)

Simon Moore (prosecution)

Simon Mount (prosecution)

Vinny Reid (British Military Police)

Teachers and Church figures

Albert and Jane Moverley (teachers)

Albert Reeves (teacher; charged with indecent assault and rape)

Allen Cox (teacher)

Barrie Baronian (teacher)

Hannah Carnihan (teacher’s daughter)

Lyle Burgoyne (lay pastor and nurse)

Neville Tosen (pastor)

Pippa Foley (teacher)

Ray Coombe (pastor)

Rick Ferret (pastor)

Roy Sanders (teacher)

Sheils Carnihan (teacher)

Tony Washington (teacher)

Victims (pseudonyms)

Belinda

Carla

Caroline

Catherine

Charlotte

Elizabeth

Fiona

Gillian

Isobel

Janet

Jeanie

Jennifer

Judith

Karen

Linda

Marion

Susan

Suzie

Various

Bill and Catherine Haigh (communications expert and his wife)

Caroline Alexander (historian)

Dea Birkett (author of Serpent in Paradise)

Herb Ford (California-based director of Pitcairn Islands Study Center)

Maurice Allward (friend of Pitcairn Island)

Maurice Bligh (descendant of William Bligh)

Nigel Jolly (skipper of the Braveheart)

Ricky Quinn (step-grandson of Terry Young)

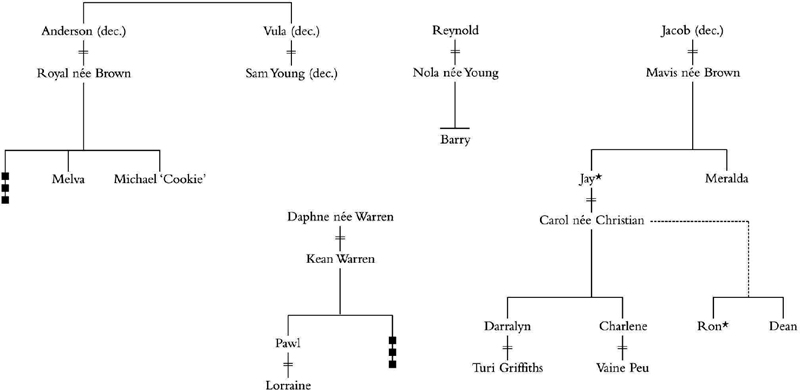

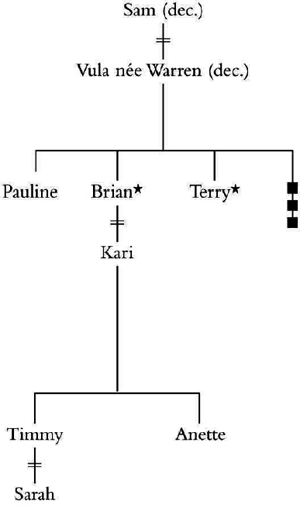

Christian clan

Brown family

Warren clan

Young family

Prologue

Pitcairn Island, a British outpost floating in a remote corner of the South Pacific, was until recently considered a tropical paradise. Seldom visited, it is a place of extreme isolation, with no airstrip and limited sea access. The rocky outcrop is inhabited by about 50 people, most of them descended from Fletcher Christian and his fellow Bounty mutineers.

The sailors fled to the island to evade British law, but for the next two centuries Pitcairn was, to all appearances, trouble-free—stabilised by religion, with negligible crime, and largely capable of running its own affairs. Just before the dawn of the new millennium, that perception was turned on its head.

In December 1999 several Pitcairn girls claimed that they had been sexually assaulted by a visiting New Zealander. By chance, a British policewoman was on the island, and one of the girls confided that she had also been raped by two local men in the past. An investigation into those allegations developed into a major inquiry that saw British detectives criss-cross the globe, interviewing dozens of Pitcairn women. Their conclusion was that nearly every girl growing up on the island in the last 40 years had been abused, and nearly every man had been an offender.

I first read about the investigation—codenamed, quite coincidentally, Operation Unique—in 2000, when snippets surfaced in the British and New Zealand media. At that time I was a relative newcomer to Sydney, where I am based as Asia – Pacific Correspondent for The Independent. The story had immediate appeal, combining Pitcairn’s mutinous history with a glimpse of life darkly played out on a far-flung island—an island that also happened to be a British colony, one of the final vestiges of Empire.

What struck me, even at that early stage, was that sexual abuse seemed to have been part of the fabric of life on Pitcairn. I tried to visualise what childhood must have been like for the victims, living there with no means of escape from their alleged assailants.

At the same time, certain Pitcairners—including women on the island—were loudly denying that children had ever been mistreated. They claimed that Pitcairn was a laid-back Polynesian society where girls matured early and were willing sexual partners. Britain, they claimed, was trying to cripple the community and force it to close, thus ridding itself of a costly burden. Who was telling the truth, I wondered: the women describing their experiences of abuse, or those portraying the affair as a British conspiracy?

For Britain, the case raised embarrassing questions about its supervision of the colony, now known as an Overseas Territory. Confronted with such serious allegations, however, the government had no choice but to act robustly. Judges and lawyers were appointed, and in 2003, after a series of legal and logistical hurdles had been surmounted, 13 men were charged with 96 offences dating back to the 1960s.

The plan was to conduct two sets of trials: the first on Pitcairn, the second in New Zealand. Preparations got under way on the island, where the accused men helped to build their own prison. The locals wanted the press excluded; as a compromise, and to prevent the place from being swamped, Britain decided to accredit just six journalists. Media organisations around the world were invited to make a pitch.

On holiday in Japan at the time, I submitted a rather hurried application, pointing out my long-standing interest in the story. I also mentioned that I would be able to file for The Independent’s sister paper, the New Zealand Herald. Shortly afterwards, I was informed that I had been chosen as a member of the media pool.

In 2004 I spent six weeks on the island, reporting on one of the most bizarre court cases imaginable. Outside court, I bumped into the main protagonists every day, which was inevitable, since I was living in the middle of their tiny community. Some of those encounters were civil; others were less so, but I was able to observe at close quarters how Pitcairn functioned: the gossip, the feuding, the claustrophobic intimacy—and the power dynamics that had allowed the abuse to flourish.

The legal saga did not end with the verdicts and sentences handed down on the island by visiting judges. It continued until late 2007, with further trials held in Auckland and the offenders appealing to every court up to the Privy Council in London. As I followed these twists and turns in both hemispheres, my mind buzzed with unanswered questions.

Why was it that many outsiders persisted in defending men who were guilty of a crime that was normally reviled: paedophilia? Why did they continue to mythologise Pitcairn, although it had failed, in such a dramatic way, to live up to its Utopian image? How far back, I asked myself, did the sexual abuse stretch—to the time of the mutineers? Why had parents not denounced the perpetrators and kept their children safe? Had anyone outside the island realised what was going on?

There were bigger questions, too. What did Pitcairn tell us about human nature and life in small, remote communities? Is this how all of us would behave if left to ourselves, with no one looking over our shoulder?

Is Pitcairn a cautionary tale—a real-life version of Lord of the Flies, that chilling story of a group of schoolboys who descend into savagery on an imaginary island?

Are there more Pitcairns out there?

CHAPTER 1 A surreal little universe in the middle of nowhere

Balancing on the deck of the Braveheart, I glanced down at the longboat rolling alongside us in the vigorous swell. Between the two vessels lay churning ocean, and a gap that narrowed and yawned alarmingly. ‘Jump,’ urged a voice behind me. Heart pounding, I leapt. A pair of muscular arms caught me and propelled me onto a wooden bench.

It was September 2004, and for the next six weeks, along with other journalists, I would be living on a lump of volcanic rock in the middle of the South Pacific. Our group had been travelling for eight days and was still some way off, separated by seas whipping themselves into furious peaks. But we could see our destination ahead of us: Pitcairn Island, the legendary home of Fletcher Christian and the Bounty mutineers.

One of Fletcher’s heirs was slouched in the back of the longboat: Randy Christian, black-bearded and massively built. Limbs that looked like gigantic steel girders sprouted from his black shorts and singlet.

When you first clap eyes on a person charged with serious crimes, they are generally seated in the dock of a court, flanked by prison guards. Randy was skippering the boat that was conveying us to shore so we could report on his trial for five rapes and seven indecent assaults. Next to him stood Jay Warren, another big man, with a dark moustache and Polynesian features. Jay, too, would soon be facing justice, for allegedly molesting a 12-year-old girl.

Looking back, it was a fitting introduction to the surreal little universe in which we were about to be immersed: a place where the sexual abuse of children is shrugged off, and not even a legal drama generating international headlines can disrupt the rhythms of daily existence. Randy and Jay, expert at picking their way through Pitcairn’s spiked collar of rocks, were in charge of the longboats, and the locals saw no irony in them coming out to fetch us. As for us, we had blithely placed our lives in the hands of men who surely did not wish us well.

Pitcairn is a crumb of land, roughly 2 miles square, and probably the most inaccessible spot on Earth. Before leaving my home in Sydney, I had found it on the map, with some difficulty: a pinprick in a vast expanse of blue, 3300 miles from New Zealand and 3600 miles from Chile. In an era when you can fly from Australia to London in a day, the journey to Pitcairn is a powerful reminder of the size of the planet. The island is one of the few places in the world without an airstrip. Too remote to be reached by helicopter, it does not even have a scheduled shipping service. Most visitors charter a yacht out of Tahiti, or hitch a lift on a trans-Pacific container ship, which takes more than a week to get there from Auckland or Panama.

As the island does not have a safe harbour, ships must heave to a mile or so offshore, where the community-owned longboats collect passengers and goods. If the seas are rough, which they often are, the captain may decide to press on without stopping. Then it can be months before another vessel passes.

Travelling in an official British party, I had taken a slightly different route, flying from Auckland to Tahiti, then waiting three days for the once-weekly connection to Mangareva, a beautiful island in the outermost reaches of French Polynesia and the nearest inhabited land to Pitcairn. The four-hour flight was broken by a refuelling stop in Hao, the atoll where the French agents who blew up the Greenpeace flagship Rainbow Warrior were briefly imprisoned. A few days later, in Mangareva’s tiny, threadbare port of Rikitea, our party boarded the Braveheart, a 110-foot former scientific research vessel, for the final leg of our odyssey: a 30-hour ocean voyage. As well as the six-person media pool, there were two British diplomats, two English police officers, and an Australian Seventh-day Adventist pastor and his wife.

Some 300 miles of open sea lie between Mangareva and Pitcairn; having been warned that the passage could be extremely choppy, I was armed with seasickness tablets, including ‘Paihia bombs’, a New Zealand remedy. What I was not prepared for was quite how lonely it would feel in that distant corner of the world’s largest ocean. We saw no other ships, just flying fish, and seabirds skimming the waves, and fields of whitecaps stretching to infinity in every direction. Only an occasional dusting of coral atolls relieved the sensation of dizzying emptiness.

On our second day, at about midday, a grey smudge appeared on the horizon: Pitcairn. The sight of it made my flesh tingle. It was quiet on deck. For the next five hours we watched as the island’s distinctive silhouette emerged and the smudge turned into a solid chunk of rock.

This was exactly what Fletcher Christian would have seen from the Bounty as he combed the South Pacific for a bolthole from the British Navy in 1790. Pitcairn proved to be ideal, and the sailors settled on the island with their Polynesian ‘wives’ and companions. Two centuries later, their descendants lived on there—just 47 of them, mostly related and sharing four surnames. And now the heirs of the famous mutineers were famous for quite different reasons.

Thirteen men had been charged as a result of a police investigation into child sexual abuse, and seven of them lived on Pitcairn, where they accounted for nearly half the adult males. Those men had insisted on their right to be tried at home; however, the last major court case on the island had been in 1898, when Harry Christian was convicted of murdering his wife and child. The island had no legal infrastructure, only a local court that had not been used for years, even for minor offences. On top of that, it had little accommodation and very few amenities.

All the key players—including judges, lawyers and court officials—were having to be shipped in, along with supplies to feed them for six weeks. British officials had chartered the Braveheart to carry everyone, together with their luggage, and a dozen crates of legal documents and evidence. With the trials due to start in four days, my group was on the boat’s final run.

After dropping anchor, we waited for the longboat, the only vessel which—unless conditions are exceptionally calm—can execute the tricky landing at Bounty Bay. The loaf-shaped island stretched out before us, silent and aloof, its shores hammered by the relentless waves. Bounty Bay, a small, rock-strewn cove, was a mere chink in an armour of tall cliffs that enclosed Pitcairn almost completely. The island was surprisingly green, with thick vegetation and ochre-red rock exposed by gashes in the escarpments.

The Braveheart hovered. Ten minutes passed. Then another ten. We chatted and joked, affecting a nonchalance that none of us felt. We scanned the scene ahead. The smile on the face of Matthew Forbes, the British diplomat with day-to-day responsibility for the territory, looked strained. Surely the islanders wouldn’t refuse to bring the boat out?

I knew that many of the locals were deeply resentful about the trials, and the consequent influx of strangers to the island. The Pitcairners were protective of their privacy and turned down most requests to visit; if the British diplomats and police officers on the Braveheart were undesirable guests, the media representatives were perhaps even less welcome. Touchy about the way they had been depicted by writers and film-makers, the islanders had more or less banned journalists since the publication in 1997 of a travel memoir, Serpent in Paradise, a closely observed study of Pitcairn life, which they detested, along with its English author, Dea Birkett.

I had been given a flavour of what lay in store for us after emailing Mike ‘Cookie’ Warren, one of the more outspoken islanders, while we were en route. I asked Cookie how the community felt about the impending trials, and expressed the hope that we journalists would be able to present a balanced picture. Cookie replied, ‘Let me begin by asking you why you are coming here when you don’t have permission from the islanders? Let me suggest that you are no different to any other reporter and journalist I know. That is, most are out to print what sells and to make money. I couldn’t care less whether what you report is balanced or not. We have already been humiliated and the presence of the press pool will only serve to reinforce that fact further.’

He added, ‘A family in trouble best deals with its troubles and problems privately and discreetly. How would you like it if your family disputes were aired on television for the whole world to see? Would you call this justice?’

The stand-off, if that was what it was, ended abruptly. A boat materialised in the distance, slicing through the waves at a hectic pace, and a few minutes later drew up beside us with a flourish. A fearsome-looking figure was planted on the prow: hulking and shaven-headed, with a bandana, a shark’s tooth necklace and several dozen earrings and studs. It looked like a pirate; it was, in fact, Pawl Warren, whom we would come to know as one of the nicest men on the island.

Randy and Jay, the two defendants, watched impassively as others helped us aboard, stowing our baggage beneath a tarpaulin. There was an awkward silence as we sat down. What does one say in that situation? ‘Hello Jay, hello Randy, hope your trial goes well’? Among the boat’s other occupants I recognised Tom Christian, tall and rangy, in a battered Panama hat: he had been Pitcairn’s radio operator for decades.

The longboat bounced off across the breakers. No one spoke to us; most of the islanders kept their gazes firmly averted. I felt ill at ease, and I sensed that my colleagues—all seasoned operators, some with experience in war zones—did too. Soon we were approaching Bounty Bay, where we shot in through a narrow entrance after veering sharp left to dodge some nasty-looking rocks.

Our reception party was modest and consisted mainly of outsiders. A handful of Pitcairners, including Tom Christian’s wife, Betty, were waiting on the concrete jetty; one or two others stood at the far end, well away from the boat, and they left after photographing our arrival. We clambered ashore and milled around uncertainly, amid the bustle of greetings and boxes being unloaded. Jay and Randy, still at work, winched the longboat up a slipway and into the boatshed, which was crowned by a big sign stating ‘Welcome to Pitcairn Island’. Another sign pointed to the ‘last resting place of H.M.S Bounty’—the spot where the skeleton of the ship, which the mutineers scuttled and burnt, lies submerged in shallow water. Long-beaked frigate birds flapped overhead, swooping down to seize fish guts from the outstretched hand of an islander who was cleaning her catch.

Snatches of the locals’ curiously cadenced language drifted over to us. Pitkern reflects their mixed roots, combining the sailors’ 18th-century English with some Tahitian words. Others around us were speaking English, but with the characteristic drawl of England’s West Country. The origins of that accent are something of a mystery.

A couple of us briefly interviewed Tom, who declared, ‘I can’t wait to get this whole mess behind us.’