скачать книгу бесплатно

Normally, the Empress would have been able to simply move astern, but a freighter, the Steel Navigator, was moored close behind her. Now she would need tugs to pull her out sideways, but these had been destroyed or crippled in the initial tremors. Furthermore, a ship moored to the east had lost her cable and drifted across the harbour, smashing into the Empress amidships.

First Captain Robinson ordered all available crew – and passengers – to turn the ship’s hoses on the decks and extinguish the embers that were drifting from the burning docks.

He then had ropes and ladders cast over the side to let the survivors trapped on the crumbling dock climb aboard. Next he tried a risky manoeuvre, engaging the Empress’s engines to shove the Steel Navigator enough to allow them to manoeuvre away from the flaming docks.

With metal grinding on metal the Empress managed to shift the freighter, inch by agonizing inch. But just as she was slowly pulling away her port propeller fouled in the Steel Navigator’s anchor cable.

She had edged about 18 m (60 ft) away from the flames; it probably wasn’t going to be enough. Sparks and embers continued to rain down on the deck. Then, fortunately, the wind turned and eased. The ship was safe – for the moment.

Now the captain turned to helping other people. He had the ship’s lifeboats lowered and formed rescue teams of crew and volunteer passengers. They then set out to shore, working through the night to ferry survivors to the ship.

The burning waters

By Sunday morning the Empress was a haven for 2,000 people, but now they faced another danger. A huge slick of burning oil was moving across the harbour towards the ship. The fouled propeller meant the Empress was still unable to steer. Captain Robinson asked the captain of a tanker, the Iris, to help. This vessel managed to tow the bow of the Empress round, allowing her to move slightly out of port to a safer anchorage.

The rescue teams kept working despite the blazing sea.

Staying behind

On 4 September, three days after the earthquake, the Empress’s fouled propeller was freed by a diver from the Japanese battleship Yamashiro, which had arrived at the harbour. The propeller was undamaged and the Empress was now free to leave.

Damage caused by the Great Kantō earthquake in Tōkyō.

But Captain Robinson decided that she should stay to help with the relief work.

For the next week the Empress of Australia re-entered the devastated harbour every morning and sent her boats ashore.

The lifeboats continued the trips, returning full of refugees, who were then either transferred from the ship to other vessels or taken to Kōbe. The ship’s crew and most of the passengers donated their personal belongings to help the survivors.

Sailing into history

Finally, on 12 September 1923, the Empress of Australia departed Yokohama. The heroism of her captain, crew and passengers was not forgotten. Captain Robinson received many awards, including the CBE and the Lloyds Silver Medal.

A group of passengers and refugees commissioned a bronze memorial tablet, which they presented to the ship in recognition of the relief efforts. When the Empress was scrapped in 1952, this tablet was handed on to Captain Robinson, then aged 82, in a special ceremony in Vancouver.

The Long Walk Home

Old rabbit-proof fence remains along Hamersley Drive, Fitzgerald River National Park, Western Australia.

The rabbit-proof fence

Rabbits are not indigenous to Australia. In 1859 an English settler in Victoria, southeast Australia released two dozen into the wild. ‘The introduction of a few rabbits could do little harm and might provide a touch of home, in addition to a spot of hunting.’ But Austin seemed to have forgotten what rabbits are good at and they were soon spreading across the continent like a plague.

Between 1901 and 1907, the government constructed one of the most ambitious wildlife containment schemes the world has ever seen. The plan was simple: cordon off the entire western side of Australia so that the rabbits couldn’t get into it. Three rabbit-proof fences crossed the country. They were one metre (3 ft) high and supported by wooden poles. No.1 Rabbit-Proof Fence ran for 1,833 km (1,139 miles) clear across the continent from Wallal Downs to Jerdacuttup. The total length of all three fences was 3,256 km (2,023 miles).

Bold though this act of segregation was, it was doomed to failure. Rabbits had already crossed west of the barrier and it was near-impossible to maintain such a structure in the harsh conditions of the Western Australian deserts, despite regular patrols by inspectors with bicycles, cars and even camels.

The stolen generation

The fence also acts as a metaphor for another act of segregation imposed on the country by the government of the time.

The white settlers of Australia had many different attitudes to the Aboriginal population. To some they were simply an inferior race. Others believed they could be assimilated into white society and have their heritage ‘bred out’ of them. Some were tolerant and understanding and of course there were many mixed-race children. It was the most divisive issue in that period of Australian history.

From 1920 to 1930 more than 100,000 mixed-race Aboriginal children were taken from their families.

Children were relocated to be educated for a useful life as a farmhand or domestic servant. The government built harsh remand homes where Dickensian conditions were the norm. The children, many as young as three, shared prison-like dormitories with barred windows. Thin blankets gave little protection against the chill nights and the food was basic. These grim educational centres, or ‘native settlements’, were often many hundreds of miles from the place the children called home. Any children caught escaping would have their heads shaved, be beaten with a strap and sent for a spell in solitary confinement.

The food in the workhouse-like ‘native settlements’ was no better than gruel. The children had few clothes and no shoes.

Molly Craig, 14, her half-sister Daisy Kadibil, 11 and their cousin Gracie Fields, 8, arrived at the Moore River Settlement north of Perth in August 1931. They had been taken from their family in Jiggalong nearly 1,600 km (1,000 miles) away and they immediately decided to return home no matter what the consequences. Their plan was simple: they would follow the rabbit-proof fence.

Walking home

The girls only had two simple dresses and two pairs of calico bloomers each. Their feet were shoeless. The only food they had was a little bread. Nevertheless, on only their second day in the settlement they hid in the dormitory and then, when no one was looking, they simply walked out into the bush. It held far fewer terrors for them than the settlement.

The girls route following the rabbit-proof fence.

The fence itself was several days’ walk away. Once they reached it they would then have several more weeks of trekking through dusty scrubland before they reached Jiggalong.

But the girls were confident that they could live off the land. Their biggest fear was getting caught by the inevitable search parties; all previous escapees had been found by Aboriginal trackers. To outfox them they would have to hide well and move fast: Molly set them a goal of covering 32 km (20 miles) a day.

‘We followed that fence, that rabbit-proof fence, all the way home from the settlement to Jiggalong. Long way, alright. We stayed in the bush hiding there for a long time.’

They made good progress at first. They hid in a rabbit warren and managed to catch, cook and eat a couple of the creatures. The weather was wet, giving them water and removing their footprints. They met two Aboriginals who gave them food and matches.

Often, when they came upon a farmhouse they simply walked up to the door and asked for help. Despite the news of their escape being widely publicised, none of the white farmers turned them in. Some gave them food and warmer clothes.

The police were on their trail, now genuinely concerned for the girls’ welfare as well as eager to return them to Moore River.

But by the third week in September the strain of life in the bush was beginning to show. Gracie, the youngest, was exhausted and the other two often had to carry her. Her legs had been slashed by thorny underbrush and become infected. After hearing from an Aboriginal woman they met that her mother had moved to nearby Wiluna, she crept aboard a train to travel there.

Molly and Daisy kept walking towards Jiggalong. They could now move faster without their younger cousin to support, but it was still brutally hard going. The rains had gone, as summer crept up on them. Every day it got hotter yet every day they were determined to cover more ground to get home quicker.

At last, in early October, the two dusty, bedraggled girls walked into Jiggalong. They had trekked for more than 1,600 km (1,000 miles) through some of the most unforgiving terrain on Earth. They were still wanted by the authorities.

But now they were home.

The story wasn’t over

The families of both girls swiftly moved house to stop the authorities taking their girls again. But, perhaps aware of what a powerful tale the girls had to tell, the government called off the chase a few weeks later.

However, although the girls’ escape is a triumphant display of endurance and indomitable human spirit, their journey didn’t bring total happiness. They were still in a land where the law discriminated against them.

Gracie’s mother wasn’t in Wiluna and she was sent back to Moore River. She became a domestic servant and died in 1983.

Molly also became a domestic servant, marrying and having two daughters. But in 1940, after she was taken to Perth with appendicitis, she was sent back to Moore River by a direct government order. Amazingly, she once again walked out of the settlement and trekked back to Jiggalong. Unfortunately, she could only take one of her daughters with her; her 3-year-old girl, Doris remained in the settlement where she was brought up. Doris later wrote the book Rabbit-Proof Fence about her mother’s first journey, which was made into a film in 2002.

Daisy’s story had the happiest outcome. She stayed in the Jiggalong area for the rest of her life, where she became a housekeeper, married and had four daughters.

Survival by Sacrifice

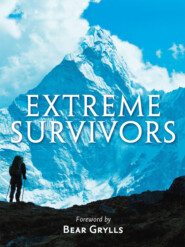

The snow-covered peaks of the Karakoram Range, Pakistan.

The height of ambition

It was no wonder that the young students were bursting with enthusiasm for the climb. Several extraordinary recent mountaineering achievements had fired the imaginations of all men who loved the mountains: Tensing and Hillary had climbed Everest just four years previously and the savage K2 had succumbed the year after. It seemed that no peak was beyond the reach of determined and able men.

But the three lads from Oxford University Mountaineering Club took their enthusiasm one step further. They wanted to be the first men to conquer the virgin spire of Haramosh, a towering 7,400 m (24,270 ft) mountain in the Karakoram range of northern Pakistan.

They would pay dearly for their high ambition. They would also display depths of bravery and self-sacrifice that belied their years.

The team finds a leader

The project was the brainchild of 23-year-old Bernard Jillott, a grammar school boy from Huddersfield. With him were John Emery, a medic who delayed his finals to join the expedition, and Rae Culbert, a 25-year-old forestry graduate from New Zealand.

The students were young, but also wise enough to know that to get a climbing permit they would need an older, more experienced leader. They asked Tony Streather, an army officer who had been on the 1950 Norwegian expedition that made the first ascent of Tirich Mir, the highest peak in the Hindu Kush at 7,690 m (25,223 ft). Initially the expedition’s transport officer, he ended up being part of the four-man team that reached the summit. He had also climbed Kangchenjunga (the world’s third highest mountain) in 1955 and two years later he was in Oxford lecturing on his experiences when the lads from the university mountaineering club collared him.

Streather was recently married and had a very small child, but it wasn’t long since he had left Pakistan and he yearned to return and see his old friends.

‘They got me into a bar, plied me with several whiskies, then asked if I would lead their expedition to Haramosh…. I suppose they caught me at a vulnerable moment and I said, “Yes, fine”.’

The team starts planning

The four didn’t always see eye-to-eye but good climbers are, by necessity, highly driven individuals who dislike compromise. Groups of them are rarely harmonious.

They decamped to the Streathers’ army bungalow in Camberley and set up their expedition headquarters. Preparations went well and by July 1957 the team was in Pakistan.

On 3 August the climbers established their base camp below the towering northern face of the mountain. They then began working their way up a long flanking route to the east.

Although it was still late summer, the weather was turning against them. Heavy snowfall often kept them in their tents for days on end. For several frustrating weeks they made little progress and by early September it was obvious (to Streather at least) that they were not going to conquer Haramosh.

But then the weather broke. The sun shone and the team decided that they could at least climb to a new high point on the mountain. It would make all their efforts worthwhile.

A step too far

On the afternoon of 15 September 1957, the four men crested a ridge at about 6,400 m (21,000 ft) and what they saw nearly tore their hearts out. The view was beautiful: a dazzling bird’s eye vista of the high Karakoram, something that only a tiny percentage of men have ever seen. No one had ever climbed higher on Haramosh. But they could also see that there was a huge, yawning gulf between them and the ultimate summit. Streather knew instantly it was time to turn back.

But Jillott insisted on continuing a little bit further, just to see over the next crest. He was roped to Emery.

Streather waited with Culbert, watching the other pair plough ahead through the crisp snow of the ridge. The north face dropped sheer away for 2,400 m (7,875 ft) on one side of the ridge but the gentle convex slope they were on seemed harmless enough. Then, suddenly, the climbers crumpled and twisted, their arms and legs flailing like marionettes.

For a split second Streather thought that Jillott and Emery were larking about. Then horror seized his heart: the whole side of the mountain was moving, dragging the two men with it. There was an eerie silence as they slid out of sight and then reality came thundering back with a roar as the avalanche cascaded over an ice cliff taking their friends into the abyss.

A spectacular view across the hundreds of mountain peaks in the Karakoram Range, Pakistan.

An avalanche in the Karakoram Range.

The rescue attempt

Streather and Culbert moved quickly. If their friends were still alive they would need supplies. They threw down a rucksack containing warm jackets and food. Agonizingly, it overshot the pair below and tumbled into a crevasse. There were more supplies cached at Camp 4, so Streather and Culbert tramped back to the tents.

Already shattered from their efforts, they had no time to rest; at that height every second counted in the race for survival. They collected vacuum flasks, food, warm clothing and rope and started to reclimb the four hour route to the accident site.

Night fell and still they kept climbing. Luckily the moon was up and the sky was cloudless so when they reached the ridge they were able to continue down into the basin.

By the time they got close to their friends the sun was rising. To their joy they heard Emery and Jillott shouting at them. Then they realized the shouts were a warning: they were about to step over the vast ice cliff that Emery and Jillott had been swept over. The fallen men told them to traverse several hundred feet right, to a point where the cliff’s steep gradient eased.

Streather had to cut steps with his ice axe all the way across the giddy traverse. They were nearly across when one of Culbert’s crampons fell from his boot and disappeared into the void.

By the time they reached Emery and Jillott it was late afternoon. Both men were weakened after a night in the open and Emery had suffered the agony of a dislocated hip when he fell although mercifully this had clicked back into its socket. Streather knew they had to start climbing back out of the basin immediately, even though he and Culbert had now been continuously on the move for thirty hours.

They had climbed 60 m (200 ft) when Culbert’s cramponless foot slipped. He fell from the ice wall and pulled everyone back down into the basin. The men tried again. This time the exhausted Jillott fell asleep in his ropes and again they tumbled back to the bottom.

They tried for a third time but Culbert’s exposed leather sole gave him no grip. Despite valiant efforts he slipped from the sheer ice and swung in space like a pendulum. He was roped to Streather who tried but could not hold his weight. Ripping his partner from his holds, Culbert hurtled back down the same cliff over which Emery and Jillott had tumbled two days earlier.

With savage irony the rescuers had become the victims.

Another night in the arms of death

The sun had set and now it was Emery and Jillott’s turn to climb through the night, returning to the ridge to collect supplies. Meanwhile Streather and Culbert shivered in the darkness of the basin below.

At dawn on 17 August, Emery and Jillot had not returned. Culbert was very weak and frostbite had numbed all feeling in his feet. Streather knew that they had to try for a fourth time to get out of the basin; their colleagues might not have made it.

They would normally have been roped together, but Streather had lost his ice axe and couldn’t have held the younger man if he had fallen. There was no point in both men perishing when one slipped, so they climbed by themselves. Now the full consequences of Culbert’s lost crampon became apparent. He was unable to get the purchase he needed to haul himself up the ice wall. As he tried to follow Streather to the ridge he kept sliding back down. Streather could barely put one foot in front of the other himself; he had no choice but to keep climbing on his own. That climb was the most savage test of endurance he would ever face.

‘I thought I was dead and I didn’t know why I was climbing, but I just knew I had to keep moving.’

Streather eventually reached the ridge and found the rucksack they had left. He was frantic with thirst, but the water bottles were frozen solid. Now all he could do was crawl back to camp.

On the way he was surprised to see a set of tracks diverge from the correct route. Back at the camp he found Emery lying, utterly exhausted, with his cramponned feet sticking out of the tent.

‘Streather asked where Jillott was. Emery said: “He’s gone.” “What do you mean – gone?” “He’s dead. Over the edge.”’

The divergent footprints had been Jillott’s. He had strayed over a precipice and fallen several thousand feet down the south side.

Emery had nearly died himself: he had tumbled into a crevasse and only managed to crawl out that morning, reaching camp a few hours before Streather.

The two who were left

Streather and Emery then talked about going back up for Culbert. But in the cold light of day they knew that was out of the question.

Streather could only get to his feet by levering himself up with ski sticks. Emery was even weaker. Physically they wouldn’t be able to accomplish it and the sad truth was that Culbert was almost certainly already dead after another night in the open.

It was time to face facts: Jillott and Culbert were dead. And unless they got a grip, they would soon be too. Streather got the stove going. Emery, the medic, gave them both penicillin jabs to protect their frostbitten hands and feet from infection.

It took them four more days to get down to base camp. Then they had the heartbreaking job of sending telegrams home to the families of Jillott and Culbert.

Home