Полная версия:

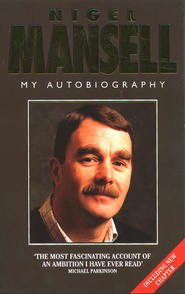

Mansell: My Autobiography

COPYRIGHT

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in paperback in 1996

Published in hardback in 1995 by CollinsWillow

Copyright © Nigel Mansell 1996

Nigel Mansell accepts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780002187039

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2016 ISBN: 9780008193362

Version: 2016-05-18

DEDICATION

To Rosanne, Chloe, Leo and Greg

for giving me the love, understanding and support

which is so necessary to achieve so much.

Without you, none of this would have been possible.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preface

Why race?

PART ONE: THE SECRET OF SUCCESS

1. My philosophy of racing

2. The best of rivals

3. The peopleâs champion

4. Family values

PART TWO: THE GREASY POLE

5. Learning the basics

6. The hungry years

7. Rosanne

8. The big break

9. Colin Chapman

10. Taking the rough with the smooth

11. The wilderness years

12. âIâm sorry, I was quite wrong about youâ

PART THREE: WINNING

13. Making it count

14. Keeping a sense of perspective

15. Bad luck comes in threes

16. Honda

17. Forza Ferrari!

18. The impossible win

19. Problems with Prost

20. Building up for the big one

21. For all the right reasons

22. World Champion at last!

23. Driven out

24. Saying goodbye to Formula 1

25. The American adventure

26. The concrete wall club gets a new member

27. âYouâre completely mad, but very quick for an old manâ

28. The stand down from McLaren

29. Fresh Perspectives

Faces in the paddock

My top ten races

Career highlights

Glossary

Index

About the Author

About the Publisher

This is a story about beating the odds through sheer determination and self-belief. It is a story about starting with nothing, taking risks and defeating the best racing drivers in the world to rewrite the record books of this most dangerous and glamorous sport.

It is about overcoming the dejection of being injured, having no money and no immediate prospects for the future. And it is about the sheer exhilaration of standing on top of the world and knowing that whatever happens next, no-one can take away from you what you have just achieved.

Nigel Mansell

Woodbury Park, Devon

NIGELâS THANKS

To the late, great Colin Chapman and his wife Hazel for giving me the first opportunity, and to Enzo Ferrari for giving me the most historic drive in motor racing and two years of wonderful memories. To Ginny and Frank Williams and to Patrick Head for the twenty-eight Grand Prix wins and the World Championship in 1992; for six years and four races it was an awful lot of fun. To Paul Newman and Carl Haas for the 1993 IndyCar World Series; and to Honda, Renault and Ford for giving me the power to win â¦

Without all these people and without the manufacturers and associated sponsors, none of the racing achievements in this book would have been possible. Rosanne and I and our family would like to thank you all for your support. A very big thank you.

PREFACE

Nigel Mansellâs life is a wonderful example of the triumph of the human spirit over adversity. He has overcome enormous hurdles throughout his career thanks to an indomitable will, total self-belief and a burning desire to succeed.

All top Grand Prix drivers are heroes, you just have to stand by the side of the track during a race weekend to see that. But Nigel stands out from the crowd for his commitment, his determination and his natural showmanship. His force of will is apparent in everything he does. I once played against him in a soccer match for journalists, photographers and drivers on the eve of the Spanish Grand Prix in 1991, a week after the pit stop fiasco in Portugal, where Nigelâs hopes of beating the great Ayrton Senna to the World Championship had followed his errant rear wheel down the pit lane.

Most of the players were there for fun, either a bit long in the tooth or too fond of their beer to be fully competitive, but Nigel played as if his life depended on it, crashing into every tackle and chasing every ball. His day ended in a twisted ankle, which swelled up like a grapefruit. He won the race that weekend of course. His injury was not play-acting, but a perfect illustration of how accident-prone the man is.

The chronicling of Nigel Mansellâs career has always been uneven. A mismatch of personalities between him and many of my colleagues in the world of journalism has led him in for some heavy criticism, some of it justified, some of it no more than blind insults. I have always been sceptical about the criticism that Nigel has come in for and fascinated to know what really makes him tick. It struck me that, although a huge public feels it can identify with him, there are very few people in the sport who actually understand what he is all about.

Nigel and I spent over 16 months devising, developing and refining this book in order to make it the definitive text on his life and racing career. In these pages Nigel explains for the first time what lies behind his philosophy of life and his psychological approach to the sport he loves. A great deal of archive research was undertaken and over 30 hours of interviews carried out with people close to Nigel. Time after time fascinating revelations from them prompted equally fascinating reflections from Nigel. We have included some of the more revealing comments, where appropriate, as notes at the end of each chapter.

Sifting through all the evidence, I believe that the starting point for understanding Nigel Mansell lies in two comments made by Williamsâ director Patrick Head and Formula 1 promoter Bernie Ecclestone, when interviewed for this book. Bernie, who knows and understands Nigel better than most in the Formula 1 pit lane, said that he is âa very simple, complex personâ while Patrick described Nigel as ânot a driver who takes well to not-winningâ. The veracity of these two statements is there for all to see in Nigelâs own words in this book.

He is a great champion who has not been fully appreciated in his own time and perhaps it will only be in history, provided it is objectively written, that the full achievement of Nigel Mansell will come to be recognised.

I am greatly indebted to Nigelâs many friends and colleagues who gave me information and insights and who pointed me towards the right areas to probe.

I would like to thank Murray Walker, Bernie Ecclestone, Gerald Donaldson, David Price, John Thornburn, Chris Hampshire, Sue Membery, Grant Bovey, Sally Blower, Anthony Marsh, Creighton Brown, Patrick Mackie, Mike Blanchet, Nigel Stroud, Frank Williams, Patrick Head, David Brown, Cesare Fiorio, Carl Haas, Paul Newman, Peter Gibbons, Bill Yeager, Derek Daly, Gerhard Berger, Keke Rosberg and Niki Lauda.

Special thanks to Peter Collins, Peter Windsor and Jim McGee for devoting a lot of time and help with my research, and to Rosanne Mansell for the stories, help with the editing and copious cups of tea. I am also greatly indebted to my father, Bill, and Sheridan Thynne for laboriously studying the draft manuscripts and making helpful suggestions.

Thanks also to the folks at CollinsWillow: Michael, Rachel and Monica and especially to Tom Whiting for an excellent piece of editing; Alberta Testanero at Soho Reprographic in New York; Bruce Jones at Autosport magazine for use of the archive; Andrew Benson for archive material and Rosalind Richards and the Springhead Trust; Ann Bradshaw, Paul Kelly and Andrew Marriott for their support; Pip for keeping me sane; and to my parents Bill and Mary and my sister Sue.

Most of all, I would like to thank Nigel for giving me the opportunity to write this book with him and for opening the door and allowing me in.

James Allen

Holland Park, London

WHY RACE?

My interest in speed came from my mother. She loved to drive fast. In the days before speed limits were introduced on British roads, she would frequently drive us at well over one hundred miles an hour without batting an eyelid. She was a very skilful driver, not at all reckless, although I do recall one time, when I was quite young, she lost control of her car on some snow. She was going too fast and caught a rut, which sent the car spinning down the middle of the road. Although it was a potentially dangerous situation I was not at all scared. I took in what was happening to the car, felt the way it lost grip on the slippery surface and watched my mother fighting the wheel to try to regain control. I was always very close to my mother and I loved riding with her in the car. I was hooked by her passion for speed.

Racing has been my life for almost as long as I can remember. I told myself at a young age that I was going to be a professional racing driver and win the World Championship and nothing ever made me deviate from that belief. There must have been millions of people over the years who thought that they would be Grand Prix drivers and win the World Championship, fewer who even made it into Formula 1 and made people believe that they might do it and fewer still who actually pulled it off.

A lot of things went wrong in the early stages of my career. I quit my job, sold my house and lived off my wife Rosanneâs wages in order to devote myself to racing; but this is a cruel sport with a voracious appetite for money and in 1978, possibly the most disastrous year of my life, Rosanne and I were left destitute, having blown five years worth of savings on a handful of Formula 3 races.

Not having any backing, I often had to make do with old, uncompetitive machinery. I had some massive accidents and was even given the last rites once by a priest whom I told, not unreasonably, to sod off. But we never gave in.

Along the way Rosanne and I were helped by a few people who believed in us and tripped up by many more who didnât. But I came through to win 31 Grands Prix, the Formula 1 World Championship and the PPG IndyCar World Series and scooped up a few records which might not be beaten for many years. For one magical week in September 1993, after I won the IndyCar series, I held both the Formula 1 and IndyCar titles at the same time.

Looking back now, it amazes me how we won through. I didnât have a great deal going for me, beyond the love and support of my wife and the certainty that I had the natural ability necessary to win and the determination not to lose sight of my goal. I did many crazy things that I wouldnât dream of doing now, because I felt so strongly that I was going to be the World Champion.

I have no doubt that without Rosanne I would not be where I am today. She has given me strength when Iâve been down, love when Iâve been desolate and she has shared in all of my successes. She has also given me three lovely children. None of this would have been possible without her.

Over the years there have been many critics. Hopefully they have been silenced. Even if they havenât found it in their hearts to admit that they were wrong when they said I would never make it, perhaps now they know it deep down.

I have always been competitive. I think that it is something you are born with. At around the age of seven I realised that I could take people on, whether it was at cards, Monopoly or competitive sports and win. At the time, it wasnât that I wanted to excel, I just wanted myself, or whatever team I was on, to win. I have always risen to a challenge, whether it be to win a bet with a golfing partner or to come through from behind to win a race. I thrive on the excitement of accepting a challenge; understanding exactly what is expected of me, focusing my mind on my objective, and then just going for it. I have won many Grands Prix like this and quite a few golf bets too.

As a child at school I played all the usual sports, like cricket, soccer and athletics and I always enjoyed competing against teams from other schools. But then another, more thrilling, pursuit began to clamour for my attention.

My introduction to motor sport came from my father. He was involved in the local kart racing scene and when he took me along for the first time at the age of nine, a whole new world of possibilities opened up. It was fast and exhilarating, it required bravery tempered by intelligence, aggression harnessed by strategy. Where before I had enjoyed the speeds my mother took me to as a passenger, now I could be in control. It was just me and the kart against the competition.

To a child, the karts looked like real racing machines. The noise and the smell made a heady cocktail and when you pushed down the accelerator, the vibrations of the engine through the plastic seat made your back tingle and your teeth chatter. It was magical. It became my world. I wanted to know everything about the machines, how they worked and more important how to make them go faster. I wanted to test their limits, to see how far I could push them through a corner before they would slide. I wanted to find new techniques for balancing the brakes and the throttle to gain more speed into corners. I wanted to drive every day, to take on other children in their machines and fight my way past them. I wanted to win.

At first I drove on a dirt track around a local allotment, then I went onto proper kart tracks. The racing bug bit deep. I won hundreds of races and many championships, and as I got more and more embroiled in the international karting scene in the late sixties and early seventies I realised that this sport would be my life. Where before I had imagined choosing a career as a fireman or astronaut, as every young boy did in those days, or becoming an engineer like my father, now I had an almost crystal clear vision of what lay ahead. My competitiveness, determination and aggression had found a focus.

I also used to love going to watch motor races. The first Grand Prix I went to was in 1962 at Aintree when Jim Clark won for Lotus by a staggering 49 seconds ahead of John Surtees in a Lola. I saw Clark race several times before his tragic death in 1968 and I used to particularly enjoy his finesse at the wheel of the Lotus Cortina Saloon cars. He had a beautifully smooth style and was certainly the fastest driver of his time. I can also remember rooting for Jackie Stewart when he was flying the flag for Britain. We went to Silverstone for the 1973 British GP, when the race had to be stopped after one lap because of a pile up on the start line. Iâll never forget watching Jackie in his Tyrrell as he went down the pit straight in the lead and then straight on at Copse Corner. I thought: âThatâs not very goodâ but it turned out that his throttle had stuck open.

Throughout the sixties and seventies as I tried to hoist myself up the greasy pole and move into their world, I followed the fortunes of the Grand Prix drivers. My favourites were James Hunt and Jody Scheckter, while I particularly liked watching Patrick Depailler and Ronnie Peterson, who were both very gutsy, aggressive drivers with a lot of style.

I never saw him race but I had a lot of respect for the legendary fifties star Juan-Manuel Fangio. To win the World Championship five times is a remarkable achievement. I have read about him and met him several times and I only wish I could have seen him race. Iâm told it was a stirring sight.

As I turned from child to adolescent and into adulthood I absorbed myself totally in motor racing, becoming totally wrapped up both in my own karting career and in the wider field of the sport. I am very much aware of the history of Grand Prix racing and I think that nowadays it is a lot more competitive than it was in the days of Fangio or Clark, although Iâm sure that the people competing in those days would dismiss that idea.

People like to compare drivers from different eras and discuss who was the greatest of all time, but the cars were so different that it makes it impossible to say who was the best; you just have to respect the records that each driver set and the history that they made. What I think you can say is that anyone who is capable of winning a World Championship in one sport could probably have done it in another discipline if they had put their minds to it, because they all have something special in them which gives them the will to win.

I had that will to win and I knew all along that, given half a chance, I could make it to the top. Against the wishes of my father, I switched from karts to single-seater racing cars in 1976 and thus began the almost impossible seventeen year journey which took me to the Formula 1 World Championship in 1992 and the IndyCar World Series in 1993. Along the way I suffered more knocks than a boxer, more rejections than an encyclopedia salesman.

In our sport it is often said that truth is stranger than fiction. The most unbelievable things can happen in motor racing, especially Formula 1, and in my case they frequently did. I can laugh now at my childhood vision of a racing driverâs life, it seems hopelessly naive in comparison to the reality.

We began writing my autobiography at possibly the worst time I can remember for trying to explain why I am a racing driver. My rival in many thrilling Grands Prix and a driver whose ability I respected enormously, Ayrton Senna, had just been killed in the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix. It was a crushing blow. The last driver to have perished in a Grand Prix car was my old team-mate Elio de Angelis in 1986, another death which hit me hard. I had seen many drivers get killed during my career, but for some of the younger ones it came as quite a shock to realise how close to death they could come on the track.

It had been twelve years since anyone had died during an actual Grand Prix. There have been huge advances made in safety since those days which certainly helped me to survive some horrific accidents, but when Senna and Roland Ratzenberger were both killed in the same weekend the whole sport was left reeling. There had been many terrible accidents in the preceding twelve years, but the drivers had got away mostly unharmed. Racing had been lucky many times, now its luck had run out.

Every time I thought about it, shivers ran down my spine. It was difficult to comprehend that Ayrton was dead; that he would never be seen again in a racing car. Ayrton was always so committed. Like me, he explored the limits and we had some thrilling no-holds barred battles where both of us drove at ten tenths the whole way. A mistake by either driver in any of those situations would have given the race to the other. It was pure competition.

He won half of his Grands Prix victories by beating me into second place and I won half of mine by beating him. We are in the Guinness Book of Records for sharing the closest finish in Grand Prix racing, at the 1986 Spanish Grand Prix, where he just pipped me by 0.014s as we crossed the finish line; a distance of just 93 centimetres after nearly 200 miles of racing. Some of the battles we had are part of the folklore of racing.

At Hungary in 1989, for example, I seized the opportunity, as we approached a back marker, to slingshot past him and grab a memorable victory. But perhaps the most enduring image of our rivalry was the duel down the long pit straight in the 1991 Spanish Grand Prix. His McLaren-Honda against my Williams-Renault; both of us flat-out on a wet track at over 180mph, with only the width of a cigarette-paper separating us, both totally committed to winning, neither prepared to give an inch. Like me, Ayrton wanted to win and was not a driver who took well to coming second.

Naturally everybody wanted to know what I thought about Ayrtonâs death and whether it would make me retire. I had achieved a great deal, I didnât need the money, I was a forty-year-old married man with three children, why continue to take the risk? The press had a field day, some writing that I was considering retirement, others saying that I was negotiating a return to Formula 1 for some unheard-of sum of money. I have never had such a hard time justifying what I do for a living as I did in the weeks following Ayrtonâs death. Every day I even questioned myself why I was doing it.

It didnât help that this period coincided with preparations for my second Indianapolis 500; a race which I remembered painfully from the year before, when I nearly won despite a severe back injury caused by hitting a wall at 180mph in Phoenix the previous month.

Every journalist and television reporter I spoke to during this period wanted me to articulate my fears about racing and my thoughts on Ayrtonâs death. They were just doing their job, of course, and it was my responsibility as a professional sportsman to talk to them, but it became thoroughly demotivating. If it were not for the fact that I am totally single-minded when it comes to racing, the barrage of questions about death could so easily have taken the edge off my competitive desire.

My passion for racing, undiminished by over thirty years of experience, was the only thing that made me put my helmet on, get into my car and drive flat out.

I am a great believer in fate, something else I inherited from my mother, and this has helped me to come to terms with some of the most difficult times in my life. If things had worked out differently and I had stayed at Williams for another couple of seasons after I won the 1992 World Championship, I would have had a great chance to win again in 1993 ⦠but then the tragedy that befell Ayrton at Imola could have happened to me.

There are three or four drivers in the world who could have been in that particular car that day, but it wasnât Prost, it wasnât Damon Hill and it wasnât me. It was Ayrton. Probably through no fault of his own, one of the greatest racing drivers of all time is dead and it could quite easily have been me. So when people ask me whether I have any regrets I tell them, âYou cannot control destiny and in our business there are occasional stark reminders of that.â As a racing driver you must believe in fate. You wouldnât get back into another car if you didnât.

Over the years I have hurt myself quite badly in racing cars and this will have prompted many a sane person to wonder why I race. Naturally pain is the farthest thing from your mind when you are in a racing car. You have to blank it out completely and focus on the job in hand. This is a quality only the very top racing drivers have. You must be able to forget an injury. Your mind must push your body beyond the pain barrier. I have often found that adrenalin is the best painkiller of all. In a hard race, even if you arenât carrying an injury, your mind pushes your body beyond the point of physical exhaustion to achieve the desired result, which is winning.