Полная версия:

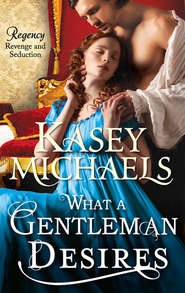

What a Gentleman Desires

Wicked intrigue unfolds in USA TODAY bestselling author Kasey Michaels’s series about the Redgraves—four siblings celebrated for their legacy of scandal and seduction…

Plagued by the scandal that once destroyed his father and now threatens his family, Valentine Redgrave dreams of dark justice. Brother to the Earl of Saltwood, with secret ties to the Crown, he won’t rest until he infiltrates and annihilates England’s most notorious hellfire club. To cross its elite members is to court destruction, yet he’s never craved a challenge more. Until he encounters enigmatic governess Daisy Marchant, who behind a plain-Jane guise harbors a private agenda and appeals to his every weakness…and desire.

Valentine’s hunt for revenge is Daisy’s key to finding her sister, who may be lost in the clutches of a deadly Society. But his seductive charm unlocks passion that can undo them both. Now, the only way to escape death and rescue their families is to trust each other in love and loyalty…even as they tread deeper into danger.

Praise for USA TODAY bestselling author

KASEY MICHAELS

“Kasey Michaels aims for the heart and never misses.”

—New York Times bestselling author Nora Roberts

“A multilayered tale.… Here is a novel that holds attention because of the intricate story, engaging characters and wonderful writing.”

—RT Book Reviews on What an Earl Wants,

4½ stars, Top Pick

“Michaels’ beloved Regency romances are witty and smart, and the second volume in her Redgrave series is no different. The lively banter, intriguing plot, fascinating twists and turns…sheer delight.”

—RT Book Reviews on What a Lady Needs, 4½ stars

“The historical elements…imbue the novel with powerful realism that will keep readers coming back.”

—Publishers Weekly on A Midsummer Night’s Sin

“A poignant and highly satisfying read…filled with simmering sensuality, subtle touches of repartee, a hero out for revenge and a heroine ripe for adventure. You’ll enjoy the ride.”

—RT Book Reviews on How to Tame a Lady

“Michaels’ new Regency miniseries is a joy.… You will laugh and even shed a tear over this touching romance.”

—RT Book Reviews on How to Tempt a Duke

“Michaels has done it again…. Witty dialogue peppers a plot full of delectable details exposing the foibles and follies of the age.”

—Publishers Weekly on The Butler Did It (starred review)

What a Gentleman Desires

Kasey Michaels

Dear Reader,

As you may know by now, many of my favorite Regency Era heroes are fops. Well, not really fops, but as is said nowadays: “But he plays one on TV.”

Valentine Redgrave, youngest brother of the Earl of Saltwood (What an Earl Wants), enacts just such a part in London society for his Regency “audience.” Boon companion, nary a serious bone in his well set-up body, Val is loved by all if admired by none, as he is, after all, only a younger son, currently without prospects; outwardly dangerous as a dandelion.

But not without wit, or else he couldn’t so quietly and successfully serve the Crown…and now, the Redgrave family in particular. Because there is trouble afoot, and the Redgraves are in it up to Valentine’s exquisitely tied cravat.

Did I mention Val has a weakness for ladies in distress? Oh, yes. His sister Kate (What a Lady Needs) vows his penchant for playing knight in shining armor will land him in deep trouble someday.

So to prove Kate’s point, I couldn’t resist plunking down Miss Daisy Marchant, governess-on-a-mission, in his path…and in his way.

Or in other words: here comes trouble!

Let’s go have some fun, and romance, and danger as these two mismatched creatures—much to their mutual surprise—stumble their way into love. And please visit me online on Facebook or at my website, www.kaseymichaels.com, to catch up on all my news.

Kasey Michaels

To Ruth Ryan Langan and the memory of her sweet Tom-babe—theirs was a love story for the ages.

Being a man would be an unbearable job—

if it weren’t for women.

—O. A. Battista

Contents

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Epilogue

PROLOGUE

ENGLISHPIGS. FRENCHDOGS.

Roasted beefs! Frog eaters!

Sworn enemies. Temporary truces.

The histories of England and France can be plotted out on a time line of wars between the two countries: a legacy of insults, envy and, paradoxically, smatterings of admiration.

But, mostly, the populace of the two countries heartily disliked each other, which did not keep them from occasionally using each other for their own gain.

English gold and wool for French brandy and silks, for instance; the boat traffic across the Straits of Dover was never ending, both in times of peace and when the two countries were at war. In peacetime this was called trade; in times of war the term was smuggling. This dance of advance and retreat, peace and conflict, had gone on so long many seemed to believe the pattern was some sort of natural order, and merely accepted the ever-changing status quo.

It was left to more inventive minds to see the larger picture, and seek a more permanent solution to this near-constant conflict. One, as it would naturally follow for some of those clever minds, which included immense personal gain.

Charles Redgrave, Sixteenth Earl of Saltwood, was just such a man. He understood enough of history, of the vulnerabilities and peculiar appetites of men, of the way the world works, to believe the unpopular French king would assist him in his dream of being named at least nominal ruler of Great Britain. He felt himself qualified for this role thanks to a thimbleful of possibly illegitimate royal Stuart blood flowing in his veins, his immense wealth and the ruthless pursuit of enough land in Kent to proclaim it his own kingdom if necessary.

When a man like Charles Redgrave dreamed, he did not dream small dreams.

In return for this assistance, Charles believed, all he had to do was assassinate the bumbling George III (and probably the Archbishop of Canterbury, as well), and hand over a large part of the English treasury to Louis XV. Louis would be popular again, and Charles happy beyond his wildest dreams and ambitions. And, at last, there would be a permanent (and mutually profitable) peace between the two nations, all thanks to Charles IV of the House of Stuart.

Really. Even if most people would agree the Earl of Saltwood had more than a few slates off his roof. Either that, or the man was so thoroughly insane he was, in fact, dangerously brilliant.

To give the earl some credit, somewhere in this idea was perhaps a kernel of a chance for possible success, although it should be pointed out that rarely is it a particularly splendid notion to begin any Grand Plan with the words: “Off with his head!”

In any event, both men were called to their final rewards before things could get out of hand, one still hated, the other unfulfilled.

Decades later, Barry Redgrave, Seventeenth Earl of Saltwood, learning of his father’s ambitions—and of his unique and titillating modus operandi—also set his sights and hopes on France, and Louis XVI, who was proving to be even more unpopular than his papa. Barry’s plan was to convince England (by fair means or foul; hopefully foul, actually, because that was much more delicious) to intercede on Louis’s behalf.

He pointed out that revolution in France could just as easily become revolution in England. Louis and his queen, the lovely Marie Antoinette of “let them eat cake” infamy, would be so grateful, and in return support Barry’s coup d’état...again, a plan ending with a Saltwood on the English throne.

But just as the Bastille fell, Barry was lying dead on the dueling field, shot in the back, purportedly by his unfaithful Spanish wife. Not that much later, the embattled Louis lost his head, literally.

Both earls had employed a rather strange route to their hoped-for success, that of gathering together secret groups of wealthy, politically and socially powerful men, in point of fact forming a corrupt and sexually deviant hellfire club known only as the Society. Whether through ambition, sexual appetite or even discreet blackmail, the Society moved beyond its original devil’s dozen thirteen members, all of whom quickly went to ground when Charles died, and most certainly repeated their ratlike scurry for the exits after the scandal of Barry Redgrave.

After nearly a half century of on-again, off-again existence as a haven for seditionists and easily-led sexually promiscuous devil worshippers, the Society was as dead as Charles and Barry.

The world could heave a collective sigh of relief, even if it never knew it perhaps should have been holding its breath.

The Saltwoods buried the history of the last two ambitious and possibly mad earls under the deepest carpet at Redgrave Manor and moved on, Barry and Maribel’s four children eventually reaching adulthood and going into Society (no, not that Society!). The scandal of Barry’s murder and their mother’s involvement, along with never quite quelled whispers of the possibility of some deliciously naughty hellfire club, moved on with them.

But that was all right with the family, who rather enjoyed being referred to as those scandalous Redgraves. The dowager countess, Lady Beatrix (Trixie) Redgrave, fairly reveled in the notoriety, actually. She certainly did nothing to discourage it at any rate, and had bedded more lovers since Charles’s death than many Englishmen had teeth left to chew their roasted beef.

And then one day about a month in the past, the Eighteenth Earl of Saltwood, Gideon Redgrave, was shocked to learn that the Society, the tawdry creation of his sire, his grandsire, intended to be the instrument of their success, was back in the treason business, this new devil’s thirteen conspiring with none other than Napoleon Bonaparte.

The Redgraves looked to each other, but only for a moment, as none of them were the sort to drag out the Society for another airing, and then began the race to identify and stop whoever in blazes was using the methods of the Society for their own gain.

The protection of England was, of course, the Redgrave family’s immediate and main concern. Of course!

But, yes, there were also all those unknown, sordid bits of Redgrave history that needed to be safely kept beneath that deep carpet....

CHAPTER ONE

1810

LORD SPENCER PERCEVAL, serving as both Prime Minister and Chancellor of Great Britain during these troubling times, sank into his favorite tub chair in his private study behind the imposing ebony door of No. 10 Downing Street. He had just moments earlier successfully concluded his most important mission of the day: seeing the last of his dozen children off to bed.

They’d been lined up like proper little soldiers, to bow or curtsy before him, and to smile as he kissed them each square in the middle of their foreheads. His wife had then adjourned to their bedroom, a twinkle in her eye—the same twinkle that had caused him to convince her to elope with him so many years ago, when her father had considered a younger Perceval unsuitable matrimonial material.

A small silver tray was placed before the prime minister. “Your evening refreshment, my lord? And I must commend you. Quite the brood you have there—or is that clutch? No, that would be hens, or ducks, or some such fowl thing. A thousand pardons. Lovely children, all of them. Stellar, really.”

Perceval relaxed the sudden death grip he’d clamped around the arms of the chair. “I should have known immediately it had to be a Redgrave. Although I would have been less surprised was it Saltwood himself. How the devil did you get in here?”

“I’m quite certain the earl sends his regards, or would, if he’d known his rascally brother planned to, as it were, drop in on you tonight. As to the how of it? A valid question from your vantage point, I’m sure,” Valentine Redgrave said, putting down the tray and taking up the facing club chair, quite precisely crossing one well-shaped leg over the other, his long-fingered hands folded in his lap. After all, he was in evening clothes, and it wouldn’t be polite to slouch, comfortable though he was in his surroundings. “But if I told you, I’d be reduced to begging your starchy under-secretary to allow me a private audience, as has been the case these past two weeks. Have you by any chance been ducking me?”

“Absolutely not,” the prime minster declared, although seemingly unable to look Val directly in the eye as he said it. “I’ve been otherwise involved.”

“As have we Redgraves, not that you seem interested in our progress.”

“Our meaning your? Now, why do I doubt that? As it is, Lord Singleton will soon be reporting to me.”

Remembering the nearly giddy communication sent to him from Redgrave Manor by his sister and tucked in with Simon Ravenbill’s official report, Valentine only smiled. “My soon-to-be new brother is otherwise engaged, I’m afraid, and forward his apologies. Behold me, his trusted messenger.”

Ah, now the prime minister was paying attention.

“Egads, you must be kidding. You Redgraves have managed to corrupt the Marquis of Singleton? I wouldn’t have thought that possible.”

“Most anything is within the realm of possibility, my lord, if one simply applies oneself. But it wasn’t all of us. Just the one, the pretty one. I’ll be honored to pass along the delightful news that you wish them happy. But now, if we’ve finished with this amicable yet hardly germane chitchat, shall we get down to cases? We’ve got serious business to discuss.”

“I know that, you insolent puppy, but this is no way to go about it. You mean to tell me Ravenbill’s so besotted he put nothing in writing for me?”

“Not knowing friend from foe, would you have done anything so potentially dangerous? No, of course you wouldn’t,” Val rejoined smoothly, as there wasn’t a Redgrave born who didn’t know how to speak the truth in order to avoid lying through his teeth. Their sister, Lady Katherine, had rather elevated clever evasion of the truth to an art form, actually. “It’s all those sweet children, isn’t it? They’ve turned your mind domestic tonight, when you should be attending to business. Quite understandable, really. Very well, I’ll recap.”

“You do that. And then I’ll have you clapped in irons for daring to accost me in my home. We’re agreed?”

“That seems only reasonable,” Val said, getting to his feet. He looked quite presentable, sitting. But standing? Ah. Few were more impressive than a tall, dark-haired Redgrave, standing, be it Gideon, Earl of Saltwood, or any of his trio of younger siblings, including Kate! The English in them seemed to recede then, and the Spanish side of them came out to play, to remind all of their mother’s fiery blood singing through their veins. Their mother, who had so disgraced the family as to shoot their father in the back in order to save her French lover on the dueling field. One couldn’t be faulted if one imagined a pistol in Valentine’s hand; after all, it was in the blood.

And then, in the space of ten even, silently counted heartbeats, Valentine bowed, as if to acknowledge the prime minister’s power over a lowly creature such as himself. “I can but humbly submit to your command. Only do be so kind as to make certain the irons are clean. This is a new jacket, you understand.”

“Bah,” said the prime minister, clearly immune to both Valentine’s physical presence and his nonsense. “Sit down, Redgrave. I’m not to be taken in like some raw schoolboy. You’re as cooperative as a room full of cats. What have you and our unexpected Romeo discovered?”

“Not me. Oh, no, not me, just as you so cleverly surmised. I’m afraid I was busy elsewhere, on a mission having much more to do with the simpler pleasures in life.”

“A woman. Perhaps several—an entire clutch of fair females. Your reputation precedes you, carefully constructed as it is, to cover your occasional work for some high-ranking government idiot who actually trusts you. But friend to that someone or not, a dank cell awaits you if you don’t soon drop this charade and come to the point.”

Ah. Spencer Perceval wasn’t stupid, and he knew about Val’s occasional service, even if he didn’t know the man or the department. Hell’s bells, he probably didn’t know the department even existed. Such was the amount of secrecy these days, what with spies everywhere from the low to the high, working for either political belief or pay, it didn’t much matter. But a too-interested Perceval was a dangerous Perceval, and to be avoided at all costs.

“A thousand apologies, I’m sure, but I find myself totally at sea. Me, working? I hardly think so. That was the answer you expected, wasn’t it?” When the prime minister smiled at last, Val neatly split his coattails and seated himself once more, this time leaning his forearms on his strong thighs and clasping his hands together between his knees, his posture all business. “All right, then, now that we’re through dancing about, fruitlessly hoping for ripe plums of information to drop out of each other’s mouths, let’s get to it. Thankfully, I do have some progress to report.”

“Spencer, darling, I thought you’d be— Oh. I didn’t realize...”

Valentine rose immediately and took his handsome, ingratiating self across the width of the intimate room, to bow over the lady’s nervously offered hand. “How very good to see you again, dear lady. I vow, it has been an age. Too long...yes, yes, indeed. Wherever has this brute been hiding you?”

“The... That is, our two youngest were ill with the measles, and I didn’t wish to— Mr. Redgrave, you can release my hand now, for I’ve been married to this good gentleman long enough to know not to quiz you on why you’re here. However, Spencer, if I might see you for a moment?”

Perceval was already beside her, and glaring at Valentine. “I’ll return directly. In the meantime, Redgrave, sit yourself down again—and for God’s sake, don’t touch anything.”

Valentine managed to look crestfallen, abashed and wickedly amused, all at one and the same time. It was also an art, this ability of his to play many roles at once for his audience, and if his brilliance didn’t impress the crusty prime minister, it still worked wonders with his lady wife, who scolded, “Spencer, that was rude.”

“Yet, alas, dear lady, a verbal spanking well deserved,” Val said, bowing once more.

He waited until the pair had adjourned to the hallway before helping himself to the wine he’d first offered the prime minister and re-taking his seat as ordered, planning to use this unexpected interlude to align his thoughts. There were things Perceval knew, things he could never know and things he needed to be told. It was all a matter of carefully—keeping to the fowl theme of the evening thus far—lining up his ducks in their proper rows.

Valentine began with a mental listing of things the prime minister knew: The Redgraves had “stumbled over,” as Gideon had so obliquely put it, the existence of a group within the government plotting to assist Bonaparte and help overthrow the Crown. As proof of his words, Gideon had handed over evidence supposedly found near Redgrave Manor that supplies meant for the king’s troops massing on the Peninsula were about to be diverted elsewhere. Gideon also had given the man two names: Archie Upton and Lord Charles Mailer, both employed by the government. Upton was dead now, Mailer was being watched. Perceval was also gifted with an entire bag of moonshine about both men being part of a “secret society” possibly operating in the area, and the prime minister had assigned Simon Ravenbill to go to the estate to investigate.

Perceval knew there was more to it than that, must be wondering about the depth of the Redgrave involvement, but had prudently not asked. Yet.

Then there was what the prime minister could not be privy to: this particular secret society could be traced back to the time of Valentine’s father and grandfather. A hellfire club with a carefully concealed history of attempted treason mixed in among the seemly mandatory satanic rites and naughty sexual antics so in vogue with such groups of powerful and ambitious men. Men who believed themselves both entitled to such pleasures and immune to discovery and scandal (until they were proven wrong, on both counts). The Redgraves wanted to help, not be thrown into prison as likely suspects!

Then there was the news Simon and Kate had sent to him, which had to be told: information, gold coin, spies and quite a bit of opium made the crossing between the beach at Redgrave Manor and France...or at least it had done until Simon and a band of unnamed local smugglers had put a stop to this traffic a scant two weeks ago.

Unfortunately, the prime minister would also have to be told the Redgraves had learned nothing more about the identities of the current members. No names, no other locations had been found. The Society had definitely used the estate, its caves and handy beach, but they hadn’t left their mark there.

There was one name, that much was true: one Society member who had acted as leader of the smugglers. But as the captured man had chosen suicide over confession, his body quietly disposed of at sea, Valentine had decided Perceval didn’t need to know of that small failure, or of Simon’s dire warning: “A leader who can convince others to kill themselves in order to protect him is a deadly dangerous man surrounded by worshipful fanatics. Be alert at all times, strike first and, for God’s sake, don’t bother attempting to capture any of them alive. If you hesitate, you’ll die, and Kate will be exceedingly out of humor with you.”

An unlovely thought all-around, Valentine believed, excluding the leavening remark about his sister, and advice he’d committed to memory. Perceval would scoff at such dramatics, being the coolheaded logical Englishman to his core, but the fiery Spanish blood in Val’s veins believed nothing impossible when it came to his fellow man.

As to the Redgraves themselves, their own family history? Ah, much had been learned there thanks to Val’s brother Gideon, their sister, Kate, and Simon Ravenbill, and even the dowager countess, who’d had the misfortune to witness the first two incarnations of the Society.

But none of that more sordid history would ever be shared with the prime minister. It was certainly true that, because of that family history, the Redgraves were better armed to defeat the Society...but they were also more vulnerable to having that salacious history made public knowledge. That would never do!

And so, with the Crown’s help—and, truthfully, preferably without it—the Redgraves would put a stop to the Society, for reasons both patriotic and personal.

Gideon had done his part, uncovering the existence of the Society in the first place, and Kate and Simon had put an end to the smuggling. Now, with their brother Maximillien on the Continent, tracking clues on that end, it was up to Valentine to take up the trail that, once followed, could destroy the Society forever, protect the Crown from the greedy Bonaparte, and tuck the scandalous Redgrave history away once and for all.

One, two, three. As simple as that. Three paths, three goals. Except they also were three giant steps, none of them easily taken, and with deadly pitfalls strewn along the way to trap the unwary.