Полная версия:

HMS Ulysses

HMS Ulysses

Alistair Maclean

Dedication

To Gisela

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Collins 1955

Copyright © Devoran Trustees Ltd 1955

Alistair MacLean asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780006135128

Ebook Edition © NOVEMBER 2009 ISBN: 9780007289318

Version: 2018-07-05

Epigraph

Come, my friends,

‘Tis not too late to seek a newer world. Push off, and sitting well in order smite The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths Of all the western stars, until I die. It may be that the gulfs will wash us down: It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles, And see the great Achilles, whom we knew. Though much is taken, much abides; and though We are not now that strength which in old days Moved earth and heaven; that which we are, we are; One equal temper of heroic hearts, Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

ALFRED LORD TENNYSON

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

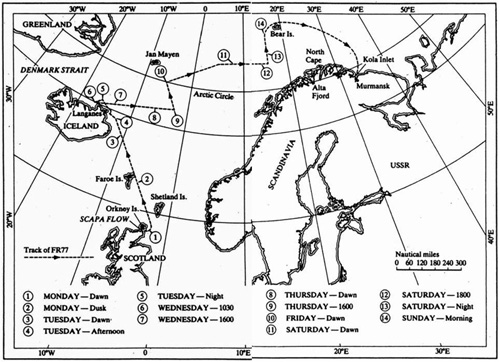

Maps

One Prelude: Sunday Afternoon

Two Monday Morning

Three Monday Afternoon

Four Monday Night

Five Tuesday

Six Tuesday Night

Seven Wednesday Night

Eight Thursday Night

Nine Friday Morning

Ten Friday Afternoon

Eleven Friday Evening

Twelve Saturday

Thirteen Saturday Afternoon

Fourteen Saturday Evening I

Fifteen Saturday Evening II

Sixteen Saturday Night

Seventeen Sunday Morning

Eighteen Epilogue

Keep Reading

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Other Books By

About the Publisher

Maps

ONE Prelude: Sunday Afternoon

Slowly, deliberately, Starr crushed out the butt of his cigarette. The gesture, Captain Vallery thought, held a curious air of decision and finality. He knew what was coming next, and, just for a moment, the sharp bitterness of defeat cut through that dull ache that never left his forehead nowadays. But it was only for a moment—he was too tired really, far too tired to care.

‘I’m sorry, gentlemen, genuinely sorry.’ Starr smiled thinly. ‘Not for the orders, I assure you—the Admiralty decision, I am personally convinced, is the only correct and justifiable one in the circumstances. But I do regret your—ah—inability to see our point of view.’

He paused, proffered his platinum cigarette case to the four men sitting with him round the table in the Rear-Admiral’s day cabin. At the four mute headshakes the smile flickered again. He selected a cigarette, slid the case back into the breast pocket of his double-breasted grey suit. Then he sat back in his chair, the smile quite gone. It was not difficult to visualize, beneath that pin-stripe sleeve, the more accustomed broad band and golden stripes of Vice-Admiral Vincent Starr, Assistant Director of Naval Operations.

‘When I flew north from London this morning,’ he continued evenly, ‘I was annoyed. I was very annoyed. I am—well, I am a fairly busy man. The First Sea Lord, I thought, was wasting my time as well as his own. When I return, I must apologize. Sir Humphrey was right. He usually is…’

His voice trailed off to a murmur, and the flintwheel of his lighter rasped through the strained silence. He leaned forward on the table and went on softly.

‘Let us be perfectly frank, gentlemen. I expected—I surely had a right to expect—every support and full co-operation from you in settling this unpleasant business with all speed. Unpleasant business?’ He smiled wryly. ‘Mincing words won’t help. Mutiny, gentlemen, is the generally accepted term for it—a capital offence, I need hardly remind you. And yet what do I find?’ His glance travelled slowly round the table.

‘Commissioned officers in His Majesty’s Navy, including a Flag-Officer, sympathising with—if not actually condoning—a lower-deck mutiny!’

He’s overstating it, Vallery thought dully. He’s provoking us. The words, the tone, were a question, a challenge inviting reply.

There was no reply. The four men seemed apathetic, indifferent. Four men, each an individual, each secure in his own personality—yet, at that moment, so strangely alike, their faces heavy and still and deeply lined, their eyes so quiet, so tired, so very old.

‘You are not convinced, gentlemen?’ he went on softly. ‘You find my choice of words a trifle—ah—disagreeable?’ He leaned back. ‘Hm…“mutiny”.’ He savoured the word slowly, compressed his lips, looked round the table again. ‘No, it doesn’t sound too good, does it, gentlemen? You would call it something else again, perhaps?’ He shook his head, bent forward, smoothed out a signal sheet below his fingers.

‘“Returned from strike on Lofotens,”’ he read out: ‘“1545—boom passed: 1610—finished with engines: 1630—provisions, stores lighters alongside, mixed seaman-stoker party detailed unload lubricating drums: 1650—reported to Captain stokers refused to obey CPO Hartley, then successively Chief Stoker Hendry, Lieutenant (E.) Grierson and Commander (E.): ringleaders apparently Stokers Riley and Petersen: 1705—refused to obey Captain: 1715—Master at Arms and Regulating PO assaulted in performance of duties.”’He looked up. ‘What duties? Trying to arrest the ringleaders?’

Vallery nodded silently.

‘“1715—seaman branch stopped work, apparently in sympathy: no violence offered: 1725—broadcast by Captain, warned of consequences: ordered to return to work: order disobeyed: 1730 —signal to C-in-C Duke of Cumberland, for assistance.”’

Starr lifted his head again, looked coldly across at Vallery.

‘Why, incidentally, the signal to the Admiral? Surely your own marines—’

‘My orders,’ Tyndall interrupted bluntly. ‘Turn our own marines against men they’ve sailed with for two and half years? Out of the question! There’s no matelot—boot-neck antipathy on this ship, Admiral Starr: they’ve been through far too much together…Anyway,’ he added dryly, ‘it’s wholly possible that the marines would have refused. And don’t forget that if we had used our own men, and they had quelled this—ah—mutiny, the Ulysses would have been finished as a fighting ship.’

Starr looked at him steadily, dropped his eyes to the signal again.

‘“1830—Marine boarding party from Cumberland: no resistance offered to boarding: attempted to arrest, six, eight suspected ringleaders: strong resistance by stokers and seamen, heavy fighting poop-deck, stokers’ mess-deck and engineers’ flat till 1900: no firearms used, but 2 dead, 6 seriously injured, 35-40 minor casualties.”’ Starr finished reading, crumpled the paper in an almost savage gesture. ‘You know, gentlemen, I believe you have a point after all.’ The voice was heavy with irony. ‘“Mutiny” is hardly the term. Fifty dead and injured: “pitched battle” would be much nearer the mark.’

The words, the tone, the lashing bite of the voice provoked no reaction whatsoever. The four men still sat motionless, expressionless, unheeding in a vast indifference.

Admiral Starr’s face hardened.

‘I’m afraid you have things just a little out of focus, gentlemen. You’ve been up here a long time and isolation distorts perspective. Must I remind senior officers that, in wartime, individual feelings, trials and sufferings are of no moment at all? The Navy, the country—they come first, last and all the time.’ He pounded the table softly, the gesture insistent in its restrained urgency. ‘Good God, gentlemen,’ he ground out, ‘the future of the world is at stake—and you, with your selfish, your inexcusable absorption in your own petty affairs, have the colossal effrontery to endanger it!’

Commander Turner smiled sardonically to himself. A pretty speech, Vincent boy, very pretty indeed—although perhaps a touch reminiscent of Victorian melodrama: the clenched teeth act was definitely overdone. Pity he didn’t stand for Parliament—he’d be a terrific asset to any Government Front Bench. Suppose the old boy’s really too honest for that, he thought in vague surprise.

‘The ringleaders will be caught and punished—heavily punished.’ The voice was harsh now, with a biting edge to it. ‘Meantime the 14th Aircraft Carrier Squadron will rendezvous at Denmark Strait as arranged, at 1030 Wednesday instead of Tuesday—we radioed Halifax and held up the sailing. You will proceed to sea at 0600 tomorrow.’ He looked across at Rear-Admiral Tyndall. ‘You will please advise all ships under your command at once, Admiral.’

Tyndall—universally known throughout the Fleet as Farmer Giles—said nothing. His ruddy features, usually so cheerful and crinkling, were set and grim: his gaze, heavy-lidded and troubled, rested on Captain Vallery and he wondered just what kind of private hell that kindly and sensitive man was suffering right then. But Vallery’s face, haggard with fatigue, told him nothing: that lean and withdrawn asceticism was the complete foil. Tyndall swore bitterly to himself.

‘I don’t really think there’s more to say, gentlemen,’ Starr went on smoothly. ‘I won’t pretend you’re in for an easy trip—you know yourselves what happened to the last three major convoys—PQ 17, FR 71 and 74. I’m afraid we haven’t yet found the answer to acoustic torpedoes and glider bombs. Further, our intelligence in Bremen and Kiel—and this is substantiated by recent experience in the Atlantic—report that the latest U-boat policy is to get the escorts first…Maybe the weather will save you.’

You vindictive old devil, Tyndall thought dispassionately. Go on, damn you—enjoy yourself.

‘At the risk of seeming rather Victorian and melodramatic’—impatiently Starr waited for Turner to stifle his sudden fit of coughing—‘we may say that the Ulysses is being given the opportunity of—ah—redeeming herself.’ He pushed back his chair. ‘After that, gentlemen, the Med. But first—FR 77 to Murmansk, come hell or high water!’ His voice broke on the last word and lifted into stridency, the anger burring through the thin veneer of suavity. ‘The Ulysses must be made to realize that the Navy will never tolerate disobedience of orders, dereliction of duty, organized revolt and sedition!’

‘Rubbish!’

Starr jerked back in his chair, knuckles whitening on the arm-rest. His glance whipped round and settled on Surgeon-Commander Brooks, on the unusually vivid blue eyes so strangely hostile now under that magnificent silver mane.

Tyndall, too, saw the angry eyes. He saw, also, the deepening colour in Brooks’s face, and moaned softly to himself. He knew the signs too well—old Socrates was about to blow his Irish top. Tyndall made to speak, then slumped back at a sharp gesture from Starr.

‘What did you say, Commander?’ The Admiral’s voice was very soft and quite toneless.

‘Rubbish,’ repeated Brooks distinctly. ‘Rubbish. That’s what I said. “Let’s be perfectly frank,” you say. Well, sir, I’m being frank. “Dereliction of duty, organized revolt and sedition” my foot! But I suppose you have to call it something, preferably something well within your own field of experience. But God only knows by what strange association and slight-of-hand mental transfer, you equate yesterday’s trouble aboard the Ulysses with the only clearly-cut code of behaviour thoroughly familiar to yourself.’ Brooks paused for a second: in the silence they heard the thin, high wail of a bosun’s pipe—a passing ship, perhaps. ‘Tell me, Admiral Starr,’ he went on quietly, ‘are we to drive out the devils of madness by whipping—a quaint old medieval custom—or maybe, sir, by drowning—remember the Gadarene swine? Or perhaps a month or two in cells, you think, is the best cure for tuberculosis?’

‘What in heaven’s name are you talking about, Brooks?’ Starr demanded angrily. ‘Gadarene swine, tuberculosis—what are you getting at, man? Go on—explain.’ He drummed his fingers impatiently on the table, eyebrows arched high into his furrowed brow. ‘I hope, Brooks,’ he went on silkily, ‘that you can justify this—ah—insolence of yours.’

‘I’m quite sure that Commander Brooks intended no insolence, sir.’ It was Captain Vallery speaking for the first time. ‘He’s only expressing—’

‘Please, Captain Vallery,’ Starr interrupted. ‘I am quite capable of judging these things for myself, I think.’ His smile was very tight. ‘Well, go on, Brooks.’

Commander Brooks looked at him soberly, speculatively.

‘Justify myself?’ He smiled wearily. ‘No, sir, I don’t think I can.’ The slight inflection of tone, the implications, were not lost on Starr, and he flushed slightly. ‘But I’ll try to explain,’ continued Brooks. ‘It may do some good.’

He sat in silence for a few seconds, elbow on the table, his hand running through the heavy silver hair—a favourite mannerism of his. Then he looked up abruptly.

‘When were you last at sea, Admiral Starr?’ he inquired.

‘Last at sea?’ Starr frowned heavily. ‘What the devil has that got to do with you, Brooks—or with the subject under discussion?’ he asked harshly.

‘A very great deal,’ Brooks retorted. ‘Would you please answer my question, Admiral?’

‘I think you know quite well, Brooks,’ Starr replied evenly, ‘that I’ve been at Naval Operations HQ in London since the outbreak of war. What are you implying, sir?’

‘Nothing. Your personal integrity and courage are not open to question. We all know that. I was merely establishing a fact.’ Brooks hitched himself forward in his chair.

‘I’m a naval doctor, Admiral Starr—I’ve been a doctor for over thirty years now.’ He smiled faintly. ‘Maybe I’m not a very good doctor, perhaps I don’t keep quite so abreast of the latest medical developments as I might, but I believe I can claim to know a great deal about human nature—this is no time for modesty—about how the mind works, about the wonderfully intricate interaction of mind and body.

‘“Isolation distorts perspective”—these were your words, Admiral Starr. “Isolation” implies a cutting off, a detachment from the world, and your implication was partly true. But—and this, sir, is the point—there are more worlds than one. The Northern Seas, the Arctic, the black-out route to Russia—these are another world, a world utterly distinct from yours. It is a world, sir, of which you cannot possibly have any conception. In effect, you are completely isolated from our world.’

Starr grunted, whether in anger or derision it was difficult to say, and cleared his throat to speak, but Brooks went on swiftly.

‘Conditions obtain there without either precedent or parallel in the history of war. The Russian Convoys, sir, are something entirely new and quite unique in the experience of mankind.’

He broke off suddenly, and gazed out through the thick glass of the scuttle at the sleet slanting heavily across the grey waters and dun hills of the Scapa anchorage. No one spoke. The Surgeon-Commander was not finished yet: a tired man takes time to marshal his thoughts.

‘Mankind, of course, can and does adapt itself to new conditions.’ Brooks spoke quietly, almost to himself. ‘Biologically and physically, they have had to do so down the ages, in order to survive. But it takes time, gentlemen, a great deal of time. You can’t compress the natural changes of twenty centuries into a couple of years: neither mind nor body can stand it. You can try, of course, and such is the fantastic resilience and toughness of man that he can tolerate it—for extremely short periods. But the limit, the saturation capacity for adaption is soon reached. Push men beyond that limit and anything can happen. I say “anything” advisedly, because we don’t yet know the precise form the crack-up will take—but crack-up there always is. It may be physical, mental, spiritual—I don’t know. But this I do know, Admiral Starr—the crew of the Ulysses has been pushed to the limit—and clear beyond.’

‘Very interesting, Commander.’ Starr’s voice was dry, sceptical. ‘Very interesting indeed—and most instructive. Unfortunately, your theory—and it’s only that, of course—is quite untenable.’

Brooks eyed him steadily.

‘That, sir, is not even a matter of opinion.’

‘Nonsense, man, nonsense!’ Starr’s face was hard in anger. ‘It’s a matter of fact. Your premises are completely false.’ Starr leaned forward, his forefinger punctuating every word. ‘This vast gulf you claim to lie between the convoys to Russia and normal operational work at sea—it just doesn’t exist. Can you point out any one factor or condition present in these Northern waters which is not to be found somewhere else in the world? Can you, Commander Brooks?’

‘No, sir.’ Brooks was quite unruffled. ‘But I can point out a frequently overlooked fact—that differences of degree and association can be much greater and have far more far-reaching effects than differences in kind. Let me explain what I mean.

‘Fear can destroy a man. Let’s admit it—fear is a natural thing. You get it in every theatre of war—but nowhere, I suggest, so intense, so continual as in the Arctic convoys.

‘Suspense, tension can break a man—any man. I’ve seen it happen too often, far, far too often. And when you’re keyed up to snapping point, sometimes for seventeen days on end, when you have constant daily reminders of what may happen to you in the shape of broken, sinking ships and broken, drowning bodies—well, we’re men, not machines. Something has to go—and does. The Admiral will not be unaware that after the last two trips we shipped nineteen officers and men to sanatoria—mental sanatoria?’

Brooks was on his feet now, his broad, strong fingers splayed over the polished table surface, his eyes boring into Starr’s.

‘Hunger burns out a man’s vitality, Admiral Starr. It saps his strength, slows his reactions, destroys the will to fight, even the will to survive. You are surprised, Admiral Starr? Hunger, you think—surely that’s impossible in the wellprovided ships of today? But it’s not impossible, Admiral Starr. It’s inevitable. You keep on sending us out when the Russian season’s over, when the nights are barely longer than the days, when twenty hours out of the twenty-four are spent on watch or at action stations, and you expect us to feed well!’ He smashed the flat of his hand on the table. ‘How the hell can we, when the cooks spend nearly all their time in the magazines, serving the turrets, or in damage control parties? Only the baker and butcher are excused—and so we live on corned-beef sandwiches. For weeks on end! Corned-beef sandwiches!’ Surgeon-Commander Brooks almost spat in disgust.

Good old Socrates, thought Turner happily, give him hell. Tyndall, too, was nodding his ponderous approval. Only Vallery was uncomfortable—not because of what Brooks was saying, but because Brooks was saying it. He, Vallery, was the captain: the coals of fire were being heaped on the wrong head.

‘Fear, suspense, hunger.’ Brooks’s voice was very low now. ‘These are the things that break a man, that destroy him as surely as fire or steel or pestilence could. These are the killers.

‘But they are nothing, Admiral Starr, just nothing at all. They are only the henchmen, the outriders, you might call them, of the Three Horsemen of the Apocalypse—cold, lack of sleep, exhaustion.

‘Do you know what it’s like up there, between Jan Mayen and Bear Island on a February night, Admiral Starr? Of course you don’t. Do you know what it’s like when there’s sixty degrees of frost in the Arctic—and it still doesn’t freeze? Do you know what it’s like when the wind, twenty degrees below zero, comes screaming off the Polar and Greenland ice-caps and slices through the thickest clothing like a scalpel? When there’s five hundred tons of ice on the deck, where five minutes’ direct exposure means frostbite, where the bows crash down into a trough and the spray hits you as solid ice, where even a torch battery dies out in the intense cold? Do you, Admiral Starr, do you?’ Brooks flung the words at him, hammered them at him.

‘And do you know what it’s like to go for days on end without sleep, for weeks with only two or three hours out of the twenty-four? Do you know the sensation, Admiral Starr? That fine-drawn feeling with every nerve in your body and cell in your brain stretched taut to breaking point, pushing you over the screaming edge of madness. Do you know it, Admiral Starr? It’s the most exquisite agony in the world, and you’d sell your friends, your family, your hopes of immortality for the blessed privilege of closing your eyes and just letting go.

‘And then there’s the tiredness, Admiral Starr, the desperate weariness that never leaves you. Partly it’s the debilitating effect of the cold, partly lack of sleep, partly the result of incessantly bad weather. You know yourself how exhausting it can be to brace yourself even for a few hours on a rolling, pitching deck: our boys have been doing it for months—gales are routine on the Arctic run. I can show you a dozen, two dozen old men, not one of them a day over twenty.’

Brooks pushed back his chair and paced restlessly across the cabin. Tyndall and Turner glanced at each other, then over at Vallery, who sat with head and shoulders bowed, eyes resting vacantly on his clasped hands on the table. For the moment, Starr might not have existed.

‘It’s a vicious, murderous circle,’ Brooks went on quickly. He was leaning against the bulkhead now, hands deep in his pockets, gazing out sightlessly through the misted scuttle. ‘The less sleep you have, the tireder you are: the more tired you become, the more you feel cold. And so it goes on. And then, all the time, there’s the hunger and the terrific tension. Everything interacts with everything else: each single factor conspires with the others to crush a man, break him physically and mentally, and lay him wide open to disease. Yes, Admiral—disease.’ He smiled into Starr’s face, and there was no laughter in his smile. ‘Pack men together like herring in a barrel, deprive ’em of every last ounce of resistance, batten ’em below decks for days at a time, and what do you get? TB It’s inevitable.’ He shrugged. ‘Sure, I’ve only isolated a few cases so far—but I know that active pulmonary TB is rife in the lower deck.