скачать книгу бесплатно

A Foreign Field

Ben Macintyre

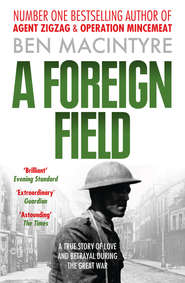

This edition does not include illustrations.A wartime romance, survival saga and murder mystery set in rural France during the First World War. From the Number 1 bestselling author of ‘Agent ZigZag’ and ‘Operation Mincemeat’.Four young British soldiers find themselves trapped behind enemy lines at the height of the fighting on the Western Front in August 1914. Unable to get back to their units, they shelter in the tiny French village of Villeret, where they are fed, clothed and protected by the villagers, including the local matriarch Madame Dessenne, the baker and his wife.The self-styled leader of the band of fugitives, Private Robert Digby, falls in love with the 20-year-old daughter of one of his protectors, and in November 1915 she gives birth to a baby girl. The child is just six months old when someone betrays the men to the Germans. They are captured, tried as spies and summarily condemned to death.Using the testimonies of the daughter, the villagers, detailed town hall records and, most movingly, the soldiers’ last letters, Ben Macintyre reconstructs an extraordinary story of love, duplicity and shame – ultimately seeking to discover through decades of village rumour the answer to the question, ‘Who betrayed Private Digby and his men?’ In this new updated edition the mystery is finally solved.This edition does not include illustrations.

A FOREIGN FIELD

A True Story of Love and Betrayal in the Great War

BEN MACINTYRE

In memory of Angus Macintyre

Table of Contents

Title Page (#ub03dcaba-ea2a-576c-a990-cdf8a7445957)

Note on Sources (#uade8e12d-8af2-514e-b256-385bde4a86bc)

Prologue (#u1bc5c891-f5dc-50cc-be34-ecf621a6ebc9)

Chapter One - The Angels of Mons (#u10a42462-6543-5ca5-b82c-c733f3c7cfa4)

Chapter Two - Villeret, 1914 (#ue38bd6d2-17c1-5895-b526-60e2078ea8d5)

Chapter Three - Born to the Smell of Gunpowder (#u56ddc4ed-fe91-5a8d-9196-7e6a2834274d)

Chapter Four - Fugitives (#u37bf4519-6220-5be2-867d-be97c4de93dd)

Chapter Five - Behind the Trenches (#u418300bd-c2e6-5ea9-84f7-34475e0c28b5)

Chapter Six - Battle Lines (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven - Rendezvous (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight - Aren’t Those Things Flowers? (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine - Sparks of Life (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten - The Englishman’s Daughter (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven - Brave British Soldier (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve - Remember Me (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen - The Somme (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen - The Wasteland (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen - Villeret, 1930 (#litres_trial_promo)

EPILOGUE - Villert, 1999 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Select Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Note on Sources (#ulink_2cbadc95-a474-51b2-b014-bf0b9cdf04d3)

This is a true story. It is based on official documents, letters, diaries, newspaper articles and contemporary writings by the participants. It would have been impossible to tell without the admirable, and peculiarly French, habit of bureaucratic history-hoarding, which prompted local officials to amass quantities of first-hand evidence from ordinary people, describing their experiences in the region behind the lines between 1914 and 1918. This information, collected immediately after the war, was carefully stored in municipal, departmental and academic archives and then almost entirely forgotten.

The story has also emerged from hundreds of hours of conversation with scores of people who were directly touched by the events described, or who learned of them from their parents, grandparents and neighbours. Their accounts are inevitably partial, in every sense, but also surprisingly consistent. Recollections of a remote time can never be perfectly accurate, but they were offered with simple honesty and I have tried to record them faithfully. What follows, then, is partly an excavation from a distant war, but also a collective memoir of a community, an attempt to reconstruct a forgotten fragment of the past through reminiscence and oral history.

Prologue (#ulink_5dd17a4a-068e-5551-9403-c60798e1de88)

The glutinous mud of Picardy caked on my shoe-soles like mortar, and damp seeped into my socks as the rain spilled from an ashen sky. In a patch of cow-trodden pasture beside the little town of Le Câtelet we stared out from beneath a canopy of umbrellas at a pitted chalk rampart, the ivystrangled remnant of a vast medieval castle, to which a small plaque had been nailed: ‘Ici ont été fusillés quatre soldats Britanniques.’ Four British soldiers were executed by firing squad on this spot. The band from the local mental institution played ‘God Save the Queen’, excruciatingly, and then someone clicked on a boom box and out crackled a reedy tape-recording of French schoolchildren reciting Wilfred Owen’s ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’.

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

An honour guard of three old men, dressed in ragged replica First World War uniforms – one English, one Scottish, one French – clutched their toy rifles and looked stern, as the drizzle dripped off their moustaches. A pair of passing cattle stopped on their way to milking and stared at us.

The day before, I had received a call from the local schoolmaster at The Times’s offices in Paris: ‘It would mean a great deal to the village to have a representative of your newspaper present when we unveil the plaque,’ he said. I had hesitated, fumbling for the polite French excuse, but the voice was pressing. ‘You must come, you will find it interesting.’

Reluctantly I set off from Paris, driving up the Autoroute du Nord past signposts – Amiens, Albert, Arras – recalling the First World War, the war to end all wars, and the very worst war, until the one that came after. Following the teacher’s precise directions, I turned off towards Saint-Quentin, across the line of the Western Front, over the River Somme, through land that had once been no-man’s and headed east along a bullet-straight Roman road into the battlefields of the war’s grand finale. No place on earth has been so indelibly brutalised by conflict. The war is still gouged into the landscape, its path traced by the ugly brick houses and uniform churches thrown together with cheap cement and Chinese labour in 1919. It is written in the shape of unexploded shells unearthed with every fresh ploughing and tossed on to the roadside, and in the cemeteries, battalions of dead marching across the fields of northern France in perfect regimental order.

Early for my meeting with the schoolteacher, I stopped beside the British graveyard at Vadancourt and wandered among the neat Commonwealth War Graves headstones with their stock, understated laments for the multitudinous dead: some known, some unknown, and the briskly facile ‘Known Unto God’, one of the many official formulations for engraved grief worked up by Rudyard Kipling. The cemetery is a small one, just a few hundred headstones, a fraction of the 720,000 British soldiers slain, who in turn made up barely one tenth of the carnage of that barbaric war, fought by highly civilised nations for no clear ideological reason.

The schoolteacher, solemn of manner and strongly redolent of lunchtime garlic, was waiting for me by the Croix d’Or restaurant in Le Câtelet, where a group of about thirty people huddled under the eaves, like damp pigeons. I was introduced as ‘Monsieur, le rédacteur du Times,’ an exaggeration of my position that made me suspect he had forgotten my name. My general greeting to the assembled was met with unsmiling curiosity, and again I wondered why I had come to a ceremony for four entirely obscure soldiers, a tiny droplet in the wave of war blood, Known Unto Nobody.

The asylum band, set up in the field behind the restaurant, now broke into a hearty, rhythm-defying rendition of something French and appropriately martial. The three amateur soldiers came to attention, of sorts, as two cars pulled up. Out of the first emerged the mayor of Le Câtelet, the préfet of the region, and his wife; from the second an elderly white-haired woman was extracted, placed in a wheelchair, and trundled across the field to the rampart wall.

After a round of formal French handshaking, the ceremony began. The previous year I had reported on the eightieth anniversary of the Battle of the Somme, a huge, poppy-packed performance with big bands and bigwigs to celebrate the very few, very old survivors. The Le Câtelet ceremony felt somehow more apt: ill-fitting uniforms on civilians, children reciting English words they did not understand, a handful of people remembering to remember in the pouring rain. I began to feel moved, in spite of myself. The préfet launched into a lofty speech about valour, honour and death. ‘See the holes in the wall?’ the teacher whispered with a gust of garlic in my ear. ‘Those are from the execution.’ As the oration rumbled on I surveyed the crowd, few under the age of seventy and some plainly as old as the event we were here to remember. Lined, peasant faces, listened hard to the official version of what the war had meant.

Suddenly I had the sensation of being watched myself. The old woman in the wheelchair, placed alongside the préfet, had also stopped listening and was staring at me. Disconcerted, I forced a smile, and tried to feign absorption in the speech, but when I sneaked a sideways glance I found her eyes were still fixed on me. Finally the préfet wound down and the village priest offered a hasty orison, again in English: ‘Our Father who art in Heaven …’ The rain stopped, the band struck up, and the military trio shouldered their plastic and marched briskly off down the street towards the town hall, where a vin d’honneur was on offer.

As the crowd drifted away, I looked around for the old woman, and then realised she was beside me, looking up. Before I could volunteer my name she spoke, in a high, faint voice and a thick Picardy accent that I could barely understand. ‘You are the Englishman,’ she said. It was not a question. The eyes that had caught my attention were now exploring my face. They were the most intensely blue eyes I had ever seen. Unnerved again, I offered a banal observation about the improvement in the weather, but she barely allowed me to finish before piping up once more.

‘Our village, Villeret,’ she gestured vaguely to the west with a mottled white hand, ‘was over there, near the front line, on the German side. When the British were retreating, in Quatorze, some soldiers were left behind and could not get back to their army across the trenches. They came to us for protection. We bandaged their wounds, fed them and we hid them from the Germans. We concealed them in our village.’

Her voice was rhythmical, as if reciting a story rehearsed by heart and scored in memory. ‘There were seven of them, brave British soldiers, and my family and the other villagers, we kept them safe. Then, one day, the Germans came to their hiding place.’ The voice trailed away, and for the first time I became aware that another person was listening: I turned to find an elderly man standing behind my shoulder, an expression of undisguised alarm on his face. She pressed on, her eyes now turned to the plaque.

‘Three of the British soldiers managed to escape from Villeret, and returned to England. Four did not. We were betrayed. The Germans captured them. They shot them against that wall, and we buried them beside the church.’ She turned back to me and smiled gravely. ‘That was in 1916. I was six months old.’

She continued, as if the events she spoke of were the moments of yesterday. ‘Those seven British soldiers were our soldiers.’ She paused again, and then murmured, the faintest whisper: ‘One of them was my father.’

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_3389bd69-c6eb-5dac-ab84-5a517c8749db)

The Angels of Mons (#ulink_3389bd69-c6eb-5dac-ab84-5a517c8749db)

On a balmy evening at the end of August in the year 1914, four young soldiers of the British army – two English and two Irish – crouched in terror under a hedgerow near the Somme River in northern France, painfully adjusting to the realisation that they were profoundly and hopelessly lost, adrift in a briefly tranquil no-man’s land somewhere between their retreating comrades and the rapidly advancing German army, the largest concentration of armed men the world had ever seen.

Privates Digby, Thorpe, Donohoe and Martin were shards from an explosion, primed for years, expected by many, desired by some and detonated just six weeks earlier when a young Bosnian Serb named Gavrilo Princip pulled a revolver in a Sarajevo backstreet and mortally wounded Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the imperial throne of Austria-Hungary. The lamps were going out all over Europe, but in the small town of Villeret, deep in the Picardy countryside, the lamps were just being lit, watched, from under a hedge, by four pairs of hungry British eyes.

The four Tommies, of whom the oldest was only thirty-six, had barely a clue as to their whereabouts, but knew well enough that they were not supposed to be there. According to official military strategy, the men should have been at least one hundred miles north, in Belgium, winning a swift and decisive victory against the Hun. But then the war was not going according to plan: neither the Schlieffen Plan, dreamt up by a dead German aristocrat, to encircle France rapidly from the north; nor France’s Plan XVII, which called for the gallant French soldiery to attack the enemy with such élan that the Germans would immediately lose heart; nor the British plan, to defend Belgian neutrality, support the French, reinforce the might of the British Empire and then go home.

Barely a fortnight earlier, the British Expeditionary Force, or BEF (this was a war that appreciated a clipped acronym), had begun crossing the Channel in troopships. They were met with beer and flowers in the August sun. Some of the soldiers were surprised, even a little disappointed, to discover they were not going to fight the French again. They swapped cap badges for kisses and then happily headed east and north towards Belgium to teach the Kaiser a lesson: 30,000 jangling horses and 80,000 men clad splendidly in khaki and self-confidence. The poet Rupert Brooke thanked God,

Who has matched us with His hour,

And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping,

With hand made sure, clear eye and sharpened

power …

To the east, the first of the 200,000 Frenchmen whose élan would be extinguished forever in a single summer month, lay rotting into the soil of Alsace and Lorraine. The German behemoth hurtled down through Belgium, sweeping aside the impregnable fortifications of Liège and Namur, to the great industrial plains where the unsuspecting British army was busily arranging itself into neat battalions. ‘The evening was still and wonderfully peaceful,’ recalled one British officer, scouting in advance of the main body of troops. ‘A dog was barking at some sheep. A girl was singing as she walked down the lane.’ He watched the darkness settle gently over the land. ‘Then, without a moment’s warning, with a suddenness that made us start and strain our eyes to see what our minds could not realise, we saw the whole horizon burst into flames. To the north, outlined against the sky, countless fires were burning … A chill of horror came over us.’

At Mons, above the Belgian border, on 23 August, the British were suddenly faced by a field-grey wave of three-quarters of a million Germans, crashing down from the north. At first the outnumbered British fought with calm efficiency, then determination, then desperation. For some, the fear was worse than the blood-letting. Retreating inside France, the British turned and fought again at Le Câteau three days later, leaving more dead on the battlefield than Wellington had lost at Waterloo. The retreat resumed. Sure hands now trembled, clear eyes clouded; the depleted army scrambled south in a desperate withdrawal that would last two weeks and take them to the edge of Paris.

An old Frenchwoman stood on her cottage doorstep and watched the ragged British soldiery stumbling through her village. As the mounted officer passed, she spat a livid stream of sarcasm at him: ‘You make a mistake,’ she hissed. (The young Captain would never forget the sting of it.) ‘The enemy is behind you. Are you not riding in the wrong direction?’

For 200 miles the German army pursued, looting, burning and wielding the weapons of summary massacre and collective retribution, for this was the policy of Schrecklichkeit – organised terror designed to inflict such horrific repression on the civilian population that it would never dare to resist. Hostages were shot and bayoneted, priests were executed, homes and towns were destroyed. At Louvain, in a signal act of desecration, the great library of more than 200,000 books was put to the torch. Some German soldiers were appalled at their own might. Ernst Rosenhainer, an educated and sensitive young infantry officer, was torn between exultation and repulsion as he watched civilians fleeing from their homes: ‘It was heart-rending to hear a woman beg a high-ranking officer, “Monsieur, protégez-nous!”,’ he wrote.

The local people watched in disbelief as refugees, Belgian and then French, streamed through the villages of the Somme and the Aisne, a ‘broken torrent of dusty misery’, dragging over-laden donkey and dog carts and recounting lurid tales of German brutality. Behind followed the BEF: horse-drawn ambulances with mangled wounded and long lines of exhausted and hungry soldiers, ‘an unthought-of confusion of men, guns, horses and wagons. All dead-beat, many wounded, all foot sore.’ At their backs, plumes of smoke marked the steady German advance in a spectacular frenzy of arson. An English officer turned around from a small incline to see ‘the whole valley and plain burning for miles’.

‘We must allow the enemy no rest,’ declared a German battalion commander. The British rearguard was forced to fight as it fled. Nerves frayed, bellies empty, minds warping from lack of sleep, some retreating soldiers dozed on the march while others began to see ghosts and castles along the way. Flight forged its own legends. The Angels of Mons’ were said to have been seen hovering over the retreat, the shimmering spectres of English bowmen killed at Agincourt five hundred years earlier, now resurrected to protect their fleeing countrymen.

The Times correspondent wrote: Amongst all the straggling units that I have seen, flotsam and jetsam in the fiercest fight in history, I saw fear in no man’s face. It was a retreating and broken army, but it was not an army of hunted men … Our losses are very great. I have seen the broken bits of many regiments.’ The lines stretched and snapped; authority dimmed, the stragglers multiplied, and the treasured distinctions of regiment and division blurred as units fragmented, re-formed, or broke away. Whatever the British reading public might have been told, most soldiers were terrified. When the horses were allowed to rest, their legs folded. Unable to march further, some men threw away their equipment and lay down to die or await the enemy. Officers who would have shot any man who acted thus a day or two earlier, did not now look back. ‘That pained look in the troubled eyes of those who fell by the way will not easily be forgotten by those who saw it. That look imposed by circumstances on spent men seemed to demand all forgiveness from officers and comrades alike, as it conveyed a helpless and dumb farewell to arms.’ The neat martial logic of the army as it had disembarked on the coast of France became hazy in retreat. Most men marched unquestioningly on. Some deserted. Some looted. Some hid. Others died of exhaustion. An officer of the Royal Fusiliers recalled a private from Hackney, ‘a most extraordinarily ugly little man in my company who could not march one bit … On the second day of the Retreat he collapsed at the side of the road and died in my arms. I have no record of his name, but as a feat of endurance and courage I cannot name his equal.’

A general noted sternly that a ‘good many cases of unnecessary straggling and looting have taken place’, and summary court martials were held. Some could not resist the lure of an empty home as a hiding place or a source of plunder, and hunger saw soldiers pulling chocolate rations from the pockets of dead men or chewing raw roots scrabbled from the fields. In Saint-Quentin, two senior British officers looked on their beaten men and agreed with the petrified city mayor that surrender would be preferable to a losing fight and the probable death of countless civilians in the crossfire. It was a most humane decision, for which both officers were immediately cashiered and disgraced.

Later, the Retreat from Mons would be rendered into history as a courageous action that had held up the Germans for long enough to ruin Field Marshal Schlieffen’s plan, ensuring that the advance would finally be stopped on the line of the River Marne. But to those who took part in it, the retreat was a grim shambles, just a few shades short of a rout, ‘a perfect débâcle’. The BEF had been severely wounded. (Most of those who survived the retreat would be hacked up at Ypres a few months later). Of the 80,000 British men who had come to France to partake in a short and decisive victory, 20,000 were either killed, wounded, captured, or found to be missing on the long retreat from Mons.

In the wake of the limping army, like the detritus from some huge and surreal travelling fair, lay packs, greatcoats, limbs, canteens, makeshift graves, horse carcasses and living men. In woods, ditches, homes and haylofts, alone and in small bands, surviving shreds of the khaki army felt the battle roll over them, and then heard it rumble south. The war correspondents of the Daily Mail and The Times observed the drooping tail of the retreat: ‘We saw no organised bodies of troops, but we met and talked to many fugitives in twos and threes, who had lost their units in disorderly retreat and for the most part had no idea where they were.’

The advancing German troops were thorough in flushing out the enemy remnants: Walter Bloem, novelist, drama critic, and a captain in the Brandenburg Grenadiers, recalled how advancing German hussars, rightly suspecting that British soldiers were hiding among the newly cut corn, ‘did not trouble to ransack every stook, but simply found that by galloping in threes or fours through a field shouting, and with lowered lances spiking a stook here and there, anyone hiding in them anywhere in the field surrendered’.

Some of the more resourceful residue contrived to fight, wriggle or wrench their way out. A band of Irishmen made it to Boulogne, and at one point stragglers headed west in such numbers that German intelligence was briefly confused into believing that the British army was making for the coastal ports. Bernard Montgomery and a small group of men from various regiments marched for three days between the marauding advance guard of German cavalry and the main infantry body. Montgomery finally outflanked the advance, linked up with the rest of the army, and went on to become Field-Marshal Montgomery of Alamein.

The BEF was a regular army, an army of professionals very different from Kitchener’s volunteer force that would follow. Here were the ‘Old Contemptibles’, recruits from the industrial slums of the north, illiterate farm boys, some ‘scallywags and minor adventurers’, men who were escaping trouble and a few who were looking for it. But unlike the conscript armies of Europe, they were experienced and well-trained: some had fought in the Boer War, and most were ‘adept in musketry, night operations and habits of concealment, matters about which the other belligerents had scarcely troubled’. For many who found themselves lost in what was now enemy territory, concealment was the first instinct. When the army finally caught its breath, about-faced and fought its way north again, sceptical commanders were not always easily persuaded that the men who emerged from barns and bushes were genuine stragglers rather than deserters. ‘It was the coward’s chance,’ thought one war correspondent. ‘Was it any wonder that some of these young men who had laughed on the way to Waterloo station, and held their heads high in the admiring gaze of London crowds, sure of their own heroism, slunk now into the backyards of French farmhouses, hid behind hedges when men in khaki passed, and told wild, incoherent tales when cornered at last by some cold-eyed officer in some town of France to which they had blundered?’

Those who never reappeared were duly recorded in the regimental files. A few months later, once the full-blown trench war of stasis was underway, their families received a letter, no different from the hundreds of thousands to follow, communicating the news, with official sadness, that a husband, son or brother was missing. Yet there were some who were neither dead nor captive.

At dawn on 26 August 1914, Robert Digby, Private No. 9368, and his comrades in the Hampshire Regiment trained their rifles across the clover and beet fields north of the small town of Haucourt, and waited for the enemy. The offensive of Le Câteau had begun. As the day brightened the sound of shelling grew steadily louder. In the darkness of the night before battle, an officer had read aloud passages from Sir Walter Scott’s poem ‘Marmion’, a thumping epic full of appropriate granite-hewn sentiment.

Where shall the traitor rest,

He, the deceiver,

Who could win maiden’s breast,

Ruin, and leave her?

In the lost battle,

Borne down by the flying,

Where mingles war’s rattle

With groans of the dying.

And when the mountain sound I heard

Which bids us be for storm prepar’d

The distant rustling of his wings,

As up his force the tempest brings.

At nine in the morning, the attack finally began, and the officers of the Hampshire Regiment had ‘the pleasure of seeing Germans coming forward in large masses’. Under cover, a handful of Gennans crept up to the Hampshires’ position and shouted ‘Retreat!’, in English. It all still seemed to be a public school game. British snipers tried to pick off the machine-gun crews and officers, distinguishable by their swords. Heavy fire was exchanged and then, inexplicably, the guns on both sides fell quiet. ‘The stillness was remarkable; even the birds were silent, as if overawed.’ Just as suddenly, the battle resumed with deafening violence. Grey troops rushed across the clover, and it was ‘as if every gun and rifle in the German army had opened fire’. Too late, the order was given for the Hampshires to withdraw. Seizing rifle and pack, Private Digby joined the throng fleeing down narrow lanes. As dusk gathered, the chaos spread. ‘We marvellously escaped annihilation,’ Private Frank Pattenden wrote in his diary. ‘It was nearly wholesale rout and slaughter.’ Lurching south, the regiment began to dissolve, mixing with other fragments of the disintegrating rump of the British army. At nightfall, a small contingent of 300 Hampshires briefly held on in the village of Ligny, but then fell back once more, leaving behind dozens of injured men in a temporary dressing station. The walking wounded made their way into the woods, and the remainder waited in the darkness.

The Hampshires tramped on through the night across fields, snatching two hours’ sleep beneath a hedgerow. In the morning they stumbled into the village of Villers-Outréaux, where a German battery awaited them, having leap-frogged the retreating British in the dark. It opened up when the Hampshires were a hundred yards away. A force of fifty men under Colonel Jackson was left to provide cover, and fought dismounted German cavalry and cyclists with rifle and bayonet as the main body of troops scrambled away. Jackson was shot in the legs and carried into the home of the local curé, where he was captured a few hours later. Private Pattenden, struggling south on bleeding feet, noted the gaps in the ranks and the many missing men: ‘I am too full for words or speech and feel paralysed as this affair is now turning into a horrible slaughter … my God it is heart breaking … we have no good officers left, our NCOs are useless as women, our nerves are all shattered and we don’t know what the end will be. Death is on every side.’ The tall figure of Private Robert Digby was last seen by his comrades clutching a bloodied arm in the temporary dressing station in Ligny. A German bullet had passed through his left forearm, narrowly missing the bone, a debilitating ‘Blighty wound’ – the sort of injury that was survivable but deemed serious enough to warrant a passage home – that men would later long for in the trenches.

When Robert Digby re-emerged from the surgeon’s tent, his arm hastily bandaged and held in a rough sling, he was no longer part of a moving mass of men, but alone. ‘I lost my army,’ he would later observe ruefully. He had also lost his Lee Enfield rifle, his bayonet, 120 rounds of ammunition, his peaked cap, his knapsack, and his bearings.

Captain Williams, the surgeon of the Hampshire Regiment, was tending the wounded when the Germans stormed into Ligny. But by then Digby had taken solitary flight. A final, brief and unemotional entry in British military records concludes his official contribution to the Great War: ‘Private Robert Digby, Wounded: 26th August, 1914.’

The previous day, William Thorpe, a tubby and genial soldier of the King’s Own Lancaster Regiment, had been sitting down to breakfast in the corn stubble above Haucourt when his war started. Thorpe and the other men were tired, having marched for three days to meet the advancing German forces, but their spirits were high. ‘The weather was perfect,’ noted one of Willie’s officers, and even the spectacle of Belgian refugees fleeing south, as ‘dense as the crowd from a race meeting but absolutely silent’, had not much dampened the mood as the King’s Own marched from the railhead. The soldiers whooped at a reconnaissance plane flying overhead, which came under ragged fire from somewhere in the rear, although Captain Higgins declared the aircraft to be British.

Lieutenant Colonel Dykes had led the column of twenty-six officers and 974 other ranks past a tiny church north of Haucourt, down a gentle slope to a stream, and then up a steep hill to a plateau on the extreme right of the British line, before he gave the order to rest. ‘A full 7 to 10 minutes was spent admonishing the troops when it was found that some had piled their weapons out of alignment.’ The time might have been better spent looking at the horizon. An hour earlier the troops had been ‘greatly reassured’, although amazed, by the sight of a French cavalry unit, clad in their remarkable plumes, breastplates, and helmets: handsome and conspicuous imperial anachronisms. Since the French advance guard was supposed to be out ahead of the British troops, an officer declared that the enemy ‘could not possibly worry us for at least three hours’. This was, therefore, an excellent moment to eat breakfast.

As they waited for the mess cart to arrive, the officers observed another group of uniformed horsemen some 500 yards away, which paused to watch the relaxing troops before trotting away. One of the younger officers quietly suggested that the cavalrymen might not be French, and was sharply told ‘not to talk nonsense’. The men were lounging and talking in groups in the quiet cornfield; the sun was growing warm when the mess cart finally rumbled up. On top of the wagon perched the regimental mascot, a small white fox terrier, clad in a patriotic Union Jack coat, that had been adopted before leaving Southampton. ‘New life came to the men’, who leapt to their feet, mess tins at the ready.