скачать книгу бесплатно

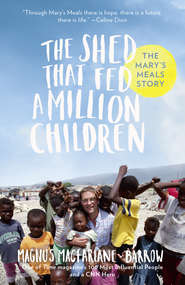

The Shed That Fed a Million Children: The Mary’s Meals Story

Magnus MacFarlane-Barrow

Speaking Volumes Christian Book of the Year 2016Mary’s Meals is born from acts of love. If you put all those many acts of sacrifice together it creates a beautiful thing.Mary’s Meals tells the inspirational and compelling story of how a cripplingly shy Salmon farmer from Argyll, Scotland, became the international CEO of a global charity that now feeds over 800,000 children a day.In 1992, Magnus MacFarlane-Barrow was enjoying a pint with his brother when he got an idea that would change his life – and radically change the lives of others. After watching a news bulletin about war-torn Bosnia, the two brothers agreed to take a week’s hiatus from work to help.What neither of them expected is that what began as a one-time road trip in a beaten-up Landrover rapidly grew to become Magnus’s life’s work – leading him to leave his job, sell his house and direct all his efforts to feeding thousands of the world’s poorest children.Magnus retells how a series of miraculous circumstances and an overwhelming display of love from those around him led to the creation of Mary’s Meals; an organisation that could hold the key to eradicating child hunger altogether. This humble, heart-warming yet powerful story has never been more relevant in our society of plenty and privilege. It will open your eyes to the extraordinary impact that one person can make.

(#u7f0fd686-32b1-581d-b684-60892ef9031c)

Copyright (#u7f0fd686-32b1-581d-b684-60892ef9031c)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2015

Copyright © Magnus MacFarlane-Barrow 2015

Magnus MacFarlane-Barrow asserts the moral right

to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008127640

Ebook Edition © May 2015 ISBN: 9780008132712

Version: 2015-12-15

Dedication (#u7f0fd686-32b1-581d-b684-60892ef9031c)

This book is for Julie, without whom there would

have been nothing at all to write about.

Thank you for loving me.

Contents

Cover (#uae19ff05-a1e1-5651-ab15-0473a9465eea)

Title Page (#ulink_df4a8748-d1ac-5342-9639-b66710c96841)

Copyright (#ulink_034ff840-7b27-50da-b30b-32313065de45)

Dedication (#ulink_afb3c532-e894-5366-a251-5d3f63a1317f)

Prologue (#ulink_c03c16c8-4602-5565-bbda-9f916ba876df)

1 Driving Lessons in a War Zone (#ulink_73f349e2-2b0d-5f6f-9fa5-bc05027ff94b)

2 A Woman Clothed with the Sun (#ulink_cb378054-baa3-5509-a794-97eae942e563)

3 Little Acts of Love (#ulink_18141b07-ed5c-5f72-ae92-f63c3676ff4d)

4 Suffer Little Children (#ulink_f3b0e7f3-bbeb-543b-a864-ffe4fc637def)

5 Into Africa (#litres_trial_promo)

6 A Famine Land (#litres_trial_promo)

7 One Cup of Porridge (#litres_trial_promo)

8 A Bumpy Road to Peace (#litres_trial_promo)

9 In Tinsel Town (#litres_trial_promo)

10 Reaching the Outcastes (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Friends in High Places (#litres_trial_promo)

12 Friends in Low Places (#litres_trial_promo)

13 Generation Hope (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Picture Section (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Thank you … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#u7f0fd686-32b1-581d-b684-60892ef9031c)

I am writing this in my father’s shed. An east wind is blowing from behind Ben Lui, whose snow-powdered flanks I can see through the window above my desk. Some of the cold air buffeting and moaning around my corrugated-iron shelter has found a way in. There is a draught gnawing my feet. I can hear someone using a power saw in the distance, perhaps my brother-in-law at the firewood, and every so often a tractor chugs down the track towards the farm.

We don’t know exactly when the shed was built. It was certainly here a long time before we arrived in 1977. It is clearly marked on a map, dated 1913, hanging in an old wood-panelled corridor of Craig Lodge (my favourite part of the house when it was our family home), meaning it has been standing here for over a hundred years. That the shed is quite clearly leaning to one side today is therefore easily forgiven and it is understandable, perhaps, that I can now hear something clanking in the wind on the roof above me.

Initially, after we arrived, it served as Dad’s garage and workshop. It was the perfect size for parking the old Land Rover, in which I would one day learn to drive. Later, he converted it into a playroom, surprising us one Christmas by opening its door to reveal a magnificent pool table. My brothers and I spent many hours enjoying that gift, while at the back of the shed, right outside my window, was our football pitch. Seumas, Fergus and I played for hours there every day, shooting at home-made wooden goals, our pounding feet creating a muddy, grassless strip. In the winter months, when the darkness arrived frustratingly early, we would sometimes turn on the lights of the shed and all the neighbouring outbuildings, in a desperate attempt to create enough illumination for at least a few extra minutes of play. Later, in our rather wild teenage years, friends would join us in the pool shed. Sometimes beer would be smuggled in. Once, when my parents were away, it was the catastrophic scene of the experimental sampling of my home-made cider. I had brewed this secretly, using apples from trees in the little orchard above where my own house stands today. I have never been able to drink cider since.

Later, after we had left home and Craig Lodge had become a Catholic retreat centre, the shed, for a few years, became a little ‘rosary factory’, where members of a resident youth community made prayer beads of various styles and colours. Then, in 1992, I asked Dad if I could borrow this shed, as well as the one next door, to store donations of aid that were arriving in response to a little appeal we were making for the refugees in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Of course he didn’t hesitate in saying yes. Indeed, he and Mum were doing most of the work involved in collecting and preparing the aid. Even if he had known then that he would never get either of his sheds back I believe he still would have agreed, mainly because he is a man more generous than any other I have met, but also because it would have given him an excuse to build some new sheds. Fortunately, this is something Dad loves to do. He is, in fact, a serial shed-builder.

Eventually, after serving for some years as a storage space for parcels of clothes, food, toiletries and medical equipment, the shed became our office, first for me as the sole employee of the charity, before I was joined by my sister Ruth and eventually a team of five. At this stage it was so cramped that some, without desks, worked with laptops on their knees. And so at this point Dad’s adjoining shed was demolished and he along with George, a very gifted friend of ours, constructed an amazing purpose-built timber office with their own hands. It is a thing of beauty and extremely practical too. But when the time came to move into the bright new office, I chose to stay here, in the old shed. This was a good decision. To some it may seem odd, perhaps even stupid, to retain the HQ of a global organization in this lopsided and tired-looking shed, in a very remote part of Scotland. But being here helps remind me how and why we began this work. Besides, I know some people, living in poverty, who would be deeply grateful to have a house as large and secure as this for their family to live in.

Indeed, among the collection of photographs and notes stuck to the wall above my desk is one of a family who lived in a house as small and more sparsely furnished than this. My meeting with them in 2002 during a terrible famine in Malawi, ten years after we had driven that first little collection of aid to Bosnia-Herzegovina, changed my life – and thousands of others – forever.

In the picture six young children are sitting beside their dying mother. She is lying on a straw mat. I remember it being unpleasantly hot inside their mud-brick house. My shirt was drenched and even though I stooped, my head rubbed their low ceiling. I felt awkward; like an oversized intruder in their tiny home at the most intimate of family moments. But they had welcomed me in warmly and so I squatted down beside them to talk. My eyes, with the help of some light that was seeping in through a small glassless window, had adjusted to the deep gloom inside the tiny space and I could see that Emma, wrapped in an old grey blanket, was wringing her hands continuously as she spoke to us.

‘There is nothing left now except to pray that someone looks after my children when I am gone,’ she had whispered, and, softly, she began to tell me about the reason for her torment.

Her husband had died a year previously, killed by AIDS, the same disease that was now about to steal her from her children. All of the adults she knew in the village were already caring for orphaned children in addition to their own. She did not know who would be willing to look after hers, she explained. Her physical pain was excruciating too. The neighbour who was looking after Emma, and who translated our conversation, was a trained ‘home-based carer’ and was doing her heroic best to ease Emma’s suffering, but she was unable to offer even a simple painkiller, never mind drugs to treat HIV/AIDS. Not that those drugs would have helped much anyway, because for them to be effective a patient needs to be eating a healthy, nutritious diet. Emma and her children had not had enough food to eat for a long time. Their hut was surrounded by parched fields in which their maize had not grown properly that year. The tummy of Chinsinsi, the youngest child on the mat, was noticeably distended from his malnutrition.

I had begun to speak to Edward, the oldest of the children. He sat straight-backed, as if wanting to appear taller than he actually was. His black T-shirt was several sizes too big for him, but unlike the filthy torn rags adorning the waists of his siblings it looked clean. He told me he was fourteen years old and explained that he spent most of his time helping his mother in their fields or in the house. Maybe I was just desperately grasping for a chink through which something brighter might steal into our depressing conversation, when I asked him what his hopes and ambitions were. I was certainly not looking for an answer that would change my life and the lives of hundreds of thousands of others.

‘I would like to have enough food to eat and I would like to be able to go to school one day,’ he replied solemnly, after a moment’s thought.

When our conversation had finished, and the children followed us out into the scorching Malawian sunlight, those simple words, spoken like a teenager’s daring dream, had already become inscribed in my heart. A cry, a scandal, a confirmation of an idea that had already begun to form, a call to action that could not be ignored; his words would become many things for me. The horrible family tragedy unfolding in that dark hut had synthesized a multitude of sufferings and intractable problems with which I had become closely acquainted during the previous ten years. And his words authenticated an inspiration recently shared with me; they were the spark that ignited the already smouldering notion that became Mary’s Meals.

On the shed wall behind me, a poster, headed boldly, proclaims our vision statement:

That every child receives one daily meal in their place of education, and that all those who have more than they need share with those who lack even the most basic things.

With every passing week, in the years since my encounter with Edward, that vision has grown ever brighter and the belief it can be realized proclaimed more confidently. We have seen repeatedly that the provision of a daily school meal really can transform the lives of the poorest children by meeting their immediate need for food, while also enabling them to enter the classroom and gain the education that can be their escape from poverty. And the number of those daily meals served by local volunteers to hungry impoverished children in schools around the world has grown in an extraordinary manner. Today, over a million children eat Mary’s Meals each school day.

I am very fond of my shed. It provides me the quiet space I often crave, while having just enough room for four or five visitors to sit with me round a table, have a cup of tea and talk. And my confinement to this office also gives my co-workers the space they most certainly need from me, an incurably untidy man. It is also the obvious place in which to write this book. The picture of Edward and his family is just one of many things stuck to my wall that illustrate landmarks on our journey: a Bosnian man playing with a dog outside his destroyed house; children laughing in a dusty African playground; a blind Liberian man with a home-made white stick and the most beautiful smile; another group of children from Dalmally – my own among them – painting the outside of the shed; a young Julie driving our truck just after I first met her; a middle-aged Julie and I meeting Pope Francis; a recent picture of me and Hollywood star Gerard Butler laughing as we carry buckets of water on our heads; a passport-sized picture of Attila, one of the first of our children in Romania to die; a card on which is written Thank You from Texas, surrounded by lots of sweet, handwritten notes from school pupils there; a postcard from Medjugorje; a simple, wooden cross made in Liberia; and a photograph of Father Tom pretending to punch someone in Haiti. Above the window, under the rusty casing of a strip light, hangs a little crucifix. Some large maps adorn the other walls – the world, India, Malawi, the New York subway and several others.

A scatter of letters and notebooks lie around my laptop. There is a polite note from the president of Malawi (where we now feed over 25 per cent of the primary-school population), thanking me for our recent meeting and for our work. Another is from someone in Haiti, pleading with us to start Mary’s Meals in some schools there with desperate need. And another anonymous one, which made me cry when I first read it:

Dear Mary’s Meals

Enclosed is a $55 check to help feed another child. This comes from a man who is in a nursing home, is wheelchair bound, right-side paralysed and unable to speak. He is financially supported by Medicare and Medicaid. The $55 represents his entire savings account. He pulled it out from two different hiding places when he heard about Mary’s Meals. I am certain it will be put to good use.

God Bless you.

I never planned to get involved in this kind of work, and certainly never set out to found an organization. I am a rather unlikely and poorly qualified person to lead such a mission. Mainly, it has unfolded despite me, through a whole series of unexpected happenings and comings-together of people, and gentle invitations responded to by all sorts of people with extraordinary love and faithfulness. The meeting with Edward, while crucial in focusing us on the work we now do, was only one more in a chain of events that had already spanned twenty years by the time he spoke those words to me. And that chain had begun to form when I was only fifteen years old, in an obscure village amid the mountains of Yugoslavia, where I had encountered another loving mother concerned about her children.

1

Driving Lessons in a War Zone (#u7f0fd686-32b1-581d-b684-60892ef9031c)

Be humble for you are made of dung. Be noble, for you are made of stars.

SERBIAN SAYING

We knew that the men who launched death from the top of the mountains overlooking the city normally slept off their hangovers in the mornings. For this reason we set off early, confident that we could get in and out of Mostar before the heavy weapons resumed their relentless task of tearing the homes, churches, mosques, vehicles and people of the city apart. Squeezed into the passenger seats beside me, for this last leg of our four-day drive from Scotland, were Father Eddie, a short, plump, middle-aged priest, and Julie, a tall, beautiful young nurse. Over the last few days the three of us had become good friends. Two nights ago, parked beside a filling station in Slovenia, we had talked long into the night. Father Eddie surprised and disturbed us a little by explaining that before leaving Scotland he’d had a feeling he might never return home and so had given away most of his worldly possessions to his parishioners. Later, Julie told us how, a few months earlier, she had awoken in the middle of the night feeling strongly that God was asking her to give up her job to help the people in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Her story moved me because of her deep faith and because it had some similarities to my own. I felt a little ashamed that when she had first phoned me to ask for a lift to Bosnia-Herzegovina I had not been at all enthusiastic about the idea. By now I was very glad she had managed to change my mind.

As we drove through a harsh Bosnian landscape of jagged rocks and thorn bushes, we prayed a rosary together and then chatted a bit nervously as I concentrated on the twisting narrow road. Soon we began to pass the remains of people’s homes. Some were reduced to piles of rubble, while those still standing had become burnt-out bullet-marked carcasses. We drove on in silence. The road began to snake downhill and Mostar appeared below us, sprawling along the Neretva, the famous river which has often been described as a dividing line between the cultures of East and West and which today was the frontline between Serbian forces and the Croat and Muslim territory through which we were driving. The minarets of mosques were visible down in the old Ottoman quarter, and for a moment I thought of my first visit to this town many years before when we had browsed little street stalls beside the river and watched young men prove their bravery by leaping from the famous Stari Most Bridge into the rushing green torrents below. On the descent into the city we were stopped at a checkpoint manned by HVO (Bosnian Croat Army) soldiers. A thin man with a machine gun on his shoulder and cigarette in his mouth walked to my open window and stared at us sullenly, his brandy breath drifting into our cab. Unsmiling, he held out his hand, and we gave him our passports and the customs papers for the medical equipment in the back of the truck. The delivery of this equipment was the reason for our journey and now, about a kilometre away, on the slopes of the city below us, we could see Mostar’s general hospital, our final destination. It was easily recognizable and we stared at the modern, shiny high-rise building, which towered above the surrounding houses. Even at that distance we could see that a shell had ripped a massive ragged hole in its side. The soldier waved us on and we drove carefully through streets of twisted metal, shards of glass, piles of rubble, burnt-out cars, chewed-up tarmac and hate-filled graffiti. We entered the hospital grounds. Outside the hospital several refrigerated trucks were parked with their engines running; makeshift morgues for a city that had long run out of space for its dead. Under the front-door canopy, three hospital staff in white overalls recognized our arrival and waved. My anxiety eased and a feeling of elation took hold of me. I was beginning to congratulate myself silently on a job well done, and found myself wondering if Julie was impressed, when I suddenly realized, a little too late, that the welcoming party’s waves were turning to urgent stop signals and their smiles to cringes. My heart hammered hard as I jammed on the brakes and heard a crunching noise above my head. In front of us, our welcome committee now doubled up in laughter and it was then I realized what had happened. Their hospital had just taken another direct hit; this time by a small, battered truck from Scotland, whose amateur driver had misjudged the height of the canopy overhanging the entrance and instead of parking under it had driven straight into it! A quick inspection revealed that I had torn a hole out of the top corner of the truck’s box, while the damage done to the hospital’s canopy was hardly significant compared to the punishment the rest of the building had been taking. The greatest, most lasting damage done was to my own ego.

We unloaded the equipment quickly and drank a hasty cup of coffee with two young male doctors. They suggested we get out of town before the shelling started and that we follow them to a safer venue for a chat. Near Medjugorje, where we were to stay the night, they stopped outside a roadside hotel that had been raked by gunfire and damaged by shells.

Over a coffee the doctors explained to us that, because of the extensive damage caused to their hospital by the shell strike, only the ground floor was now in operation. The building was becoming impossibly overcrowded and they were lacking even the most basic of medical supplies. They were particularly delighted with the external fixators we had brought them as they were treating so many patients with smashed limbs, and they urged us to deliver them more supplies. We explained to them that Julie had travelled with me because she was a nurse and was willing to give up her job in Scotland to work as a volunteer here. They replied that they had enough nurses but not enough medical equipment. They suggested that perhaps Julie join me in my efforts to collect surplus medical equipment in Scotland because by now they had realized that as well as not being able to drive a truck particularly well, I also didn’t know the first thing about medical supplies, so someone who did would have to get involved if I was to be of much further help to them. I was surprised by how delighted I felt at the prospect of Julie working with me, but just mumbled that we could mull it over. Julie said something similar and I decided I had better not get my hopes up. From medical matters the conversation drifted inevitably to the war situation. The doctors described how the ‘Chetniks’ on the mountains were now targeting not only the hospital, but ambulances too. Several had been destroyed while trying to carry patients to the hospital. By now they had swapped their Turkish coffees for Slivovitz (a local plum brandy) and they began to express how they felt about the war. They were filled with hatred towards their enemies the ‘Chetniks’ and it became a disturbing conversation. The two doctors, who had been talking to us for hours about what they needed to heal badly injured people, began to describe the terrible things they would do to any Chetnik soldier they could get their hands on. Clutching lists of urgently needed medical items, we took our leave, promising we would return with more supplies as soon as possible.

This was the fifth trip I had made to Bosnia-Herzegovina in quick succession, and on each previous one I had been accompanied by a different family member or friend. Each had been a precipitous learning curve for a twenty-five-year-old fish farmer who had not ever aspired to be a long-distance truck driver. I discovered a whole world with its own culture, inhabited by long-distance drivers, one which was not always welcoming or easy to understand. Language itself was a problem. There were new technical terms to learn such as the ‘tachograph’ (the device which records the driver’s hours and speed at the wheel) or ‘spedition’ (the agents who prepare necessary customs papers at border crossings). This was made all the harder by our lack of European languages and our Scottish accents. On one of my early trips my co-driver was Robert Cassidy, a good friend from Glasgow, whose accent therefore was stronger than my own one from Argyll. We were driving a 7.5 tonne truck full of donated Scottish potatoes to Zagreb. It was midwinter and bitterly cold. We slept in the back of the truck at night between the pallets of potatoes, and we woke one morning near the Austrian–Slovenian border to find that our large bottles of drinking water had frozen solid, while a sign at the petrol station told us it was six degrees below freezing. One of the new technical terms we were about to learn on this trip was ‘plomb’. This refers to the small seal made of lead, which the customs officials place on the back of a truck when you enter their country, so that when you exit you can prove you transited their territory without opening the trailer and depositing goods. But we didn’t know yet what this term meant and with growing irritation a customs inspector barked a one-word question through his glass window at us. ‘Plomb?’ He wanted to know if our truck was sealed. After answering this repeated question with a blank stare several times, Robert finally answered in his finest Glaswegian accent. ‘Nae plums, just tatties. Loads of tatties.’ This time it was the turn of the customs officer to answer with a bemused stare. He didn’t even know what language to reply to us in.

At this time some of the bridges on the main Adriatic coastal route that took us towards our routes into central Bosnia-Herzegovina had been destroyed by shells, and so to travel that way involved taking a small ferry to Pag (a long, narrow island running parallel to the coast), driving its length and getting a ferry back on to the mainland further south. On one occasion Ken, my brother-in-law and co-driver on this particular trip, and I joined a queue of hundreds of trucks waiting for a small makeshift ferry, on a road that certainly hadn’t been designed for large vehicles, just as an incredibly ferocious storm blew up. The ferries stopped sailing and, like all the other drivers, we found ourselves trapped in our cabs while a freezing wind blasted our truck, rocking it back and forth so violently it felt like we would be blown over. There was no way to turn a truck on that narrow road and so we all had no option but to wait for the storm to blow over. The only food we had in the cab was a large box of Twix chocolate bars, which we carefully eked out over the next forty-eight hours. A couple of times, to meet the call of nature, we fought with the door to climb outside and found ourselves slipping on a frozen stream of truck drivers’ urine that ran from the top of the hill to the little jetty at the bottom of the winding road. I made a mental note to carry a more varied, nutritious stock of emergency food supplies in future – or at the very least a greater variety of chocolate bars.

I also began to learn, on these early trips, that the donations of aid in the back of our truck were not always the most important things we brought to those in desperate need. My father and I once delivered aid to a little institution for children with special needs near the port of Zadar. At this time the Serb forces were attacking that part of the Croatian coast and we could hear the rumble of shells in the distance as we arrived outside the shabby little building. We found rows of children confined to cots, dressed in ragged pyjamas, and some terrified staff trying to care for them. Not only were they stressed about no longer having even the most basic supplies for the children, but the war was getting closer and they knew that to flee quickly and suddenly with these children would not be possible. As we unloaded our boxes of aid from the back of our truck, the staff’s delight soon evaporated as a shell exploded much closer to the village. And then another. They urged us to unload as quickly as possible and to get back on the road north immediately. As soon as I passed the last box from the back of the truck I said my goodbyes, jumped into the driver’s seat and revved the engine ready to go. A few seconds went by and I became annoyed that Dad hadn’t climbed into the seat beside me. When I looked in my rear-view mirror, I saw him hugging the most distraught nurse and giving her words of comfort and a promise of prayers. Only then did he climb in and we sped off. Thirty years later, when I heard Pope Francis use the term ‘sin of efficiency’ for the first time, I thought immediately of this incident. The Pope was reminding those of us who work with people in poverty, that real charity is not just about material goods or ‘projects’ and their ‘effectiveness’. It should also be about looking people in the eye, spending time with them and recognizing them as brothers or sisters. But even today I am not sure whether Dad’s hug had to take quite that long!

On each of those drives across Europe, as we came closer to our usual destination, Medjugorje, we would invariably see all sorts of other vehicles heading for that same world-renowned place of pilgrimage. Little convoys of small trucks like ours, solitary vans or family cars pulling trailers piled high with clothes, food and medicine, all converged on that little village in the mountains of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Flags, car stickers or home-made signs proclaimed their mission and their homeland, and gave clues to their destination. While we loved the opportunity to return to Medjugorje, given that our lives had been changed there many years earlier, we started to consider whether we should also begin taking our aid to other overlooked places, where less help was arriving but where even greater numbers of refugees were suffering.

One such place was Zagreb, the capital of Croatia, where thousands of desperate people were arriving from areas that were being ‘ethnically cleansed’ by the Serbs. At this stage nearly a third of a newly independent Croatia was under Serbian control, and war raged along all of the front lines of a country fighting desperately for its existence. Refugees and displaced people, Croats and Muslims from both Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, were pouring into the city having lost their homes, their possessions, and often their families. Living in Zagreb was a remarkable man called Dr Marijo Živković. A mutual friend from Glasgow had suggested we meet. He had explained to us that Marijo was doing wonderful work for refugees and poor people, and also mentioned that he was a well-known and outspoken Catholic who had been persecuted by the communist regime for that reason. We arranged to meet him at the office of a Muslim organization called Merhamet with whom we were working to distribute medical aid. We had earlier that day arrived with an anaesthetic machine they had urgently requested and had spent the morning with a passionate young doctor and his Merhamet colleagues, learning more about their work and how we might help further. We were a little nervous about the meeting with Dr Marijo because, tragically, the Croats (mainly Catholic) and Muslims, who had until recently been allies in Bosnia-Herzegovina while fighting their common enemy, the Serbs, were now at war with each other, and a burning hatred was now raging between these two peoples. How stupid and thoughtless had we been to have invited a well-known Catholic Croat to come and meet with us while we were with our Muslim friends? We sensed that our hosts were also a little apprehensive and an awkward silence had taken hold of the hot stuffy room by the time Marijo finally arrived. Tall and broad-shouldered, he burst in cradling a huge pile of frozen chocolate bars.

‘Please take some!’ he laughed, approaching each of us in turn, inviting us to help ourselves to the treats on offer, as if he were an old friend of everyone in the room. Eventually, we were able to shake hands and introduce ourselves, and amid much laughter Marijo explained to us, in very good English, the story of the ice cream.

‘You see, a large Italian company wanted to donate all this ice cream – half a million ice creams! They contacted lots of the large aid organizations. Each said it was impossible for them to accept – a crazy, ridiculous idea, to send ice cream in mid-summer to people who had no way of storing it in freezers. Eventually someone told the Italians they should phone me and when they did, of course I said yes! How could you say no to all that ice cream when it could make so many people happy? So before it arrived I phoned lots of people to ask them to be ready to take quantities and give out to all their friends and everyone they meet – to take them to children – to schools. And I am sure they are nutritious too …’ He guffawed as he began to eat another one.

‘So today all over Zagreb people are eating free ice cream!’ He roared with laughter again and slapped the backs of his new Muslim friends, who were by now also in peals of laughter.

This was the first of many lessons I learnt from Dr Marijo over the coming years. He had a wonderful appreciation of the art of giving and receiving gifts. He didn’t like to use the word ‘aid’. He liked to talk about ‘gifts’. And rather than saying no to gifts that were offered, he found ingenious ways to accept. Before the war was over, he had even managed to better the famous ice-cream distribution incident when we asked him if he could accept hundreds of tonnes of potatoes from Scottish farmers. This time he solved the logistics, which seemed impossible to others, simply by unloading them all into a huge pile in a public square in the city centre. He then got on the public radio and invited the people of Zagreb to come and help themselves! The hungry inhabitants of the capital responded quickly and every last potato found a good home within hours.

Dr Marijo, an economist by training, had for many years been involved in promoting Catholic teaching on family issues in the former communist state of Yugoslavia. He began to be invited to give talks in various parts of the world and eventually he and his wife, Darka, were invited by the Pope to become members of the Pontifical Council for the Family. The communist authorities finally lost patience and took away his passport to prevent him from travelling. Undeterred, he instead began to organize international conferences in Zagreb, inviting people from many countries there, until eventually he was given his passport back. Meanwhile he and his family founded an organization called the Family Centre, to provide pregnant women living in poverty with practical help – baby clothing, food, prams, nappies, and so on. The desperate need for basic essential items – and not just those needed by babies – had become huge among the arriving refugees and the general population, and thus the Family Centre now devoted its attention to receiving and distributing goods to all in desperate need. After we had established that the Family Centre was giving aid to all, regardless of their ethnicity or religion (in fact the majority of the aid was being given to Muslims), we began delivering truckloads of Scottish gifts to Marijo’s old railway warehouse. On each visit we got to know Marijo, his wife Darka and their children better, often sleeping one night in their house before beginning our homeward journey. A man with a formidable intellect and a love of speaking publicly, he regaled us constantly with his words of wisdom and philosophy. He was not shy to speak of his various impressive achievements, but often these would be followed by him saying: ‘My greatest achievement in life is to have met and married Darka … my second greatest achievement in life are my five children … my only regret is we did not have more …’ He spoke about family – its beauty and importance – in a profound and sincere way.

Much of the aid we distributed with Marijo was delivered to various makeshift refugee camps, full mainly of women and children. In rows of overcrowded wooden cabins, built originally as accommodation for migrant workers, lived a group of women and children from the town of Kozarac in northern Bosnia-Herzegovina. Despite their trauma, or perhaps because of it, some of them wanted to speak about the horrors they had endured. Before the war, the overwhelming majority of their town was Muslim. For some time that area had been controlled by Serbs and the inhabitants in Kozarac were among the first to experience the evil of ‘ethnic cleansing’. The women told us how they had fled to the forest as the Serbs shelled their town, and when the last few Muslim fighters eventually surrendered, they heard the Serbs announce, through loudspeakers, that those in the trees should surrender and come to the road and that none would be harmed. Crowds of them, waving makeshift white flags, made their way out of the woods and assembled on the road. Shells then began to rain down among them, killing and maiming hundreds. When the shelling stopped, the Serb soldiers lined up the survivors and separated out all the men of fighting age. Many of them, who were identified as being leaders or high-profile members of their community, were shot or had their throats slit by the side of the road. Some of those telling the stories had seen this happen to their husbands, fathers and sons. The rest of the men were taken to newly set-up concentration camps. Huddled in their overcrowded cabins, the women told us their stories in the belief that no one in the outside world knew or understood what was happening. They would insist on sharing some of the food we had brought with us and also asked if it would be OK if they set aside a quarter of the gifts we had brought, to smuggle to refugees they knew of still in hiding in northern Bosnia-Herzegovina, who were even more hungry than them. I came away from those encounters with a mixture of feelings. Each of these horror stories made me feel more outraged and angry at these ‘barbaric Chetniks’. I found it difficult to remain impartial in this war that I had no part in, or to remember that I was only hearing one side of this tragic story. So often, too, I was deeply moved by the kindness and strength of spirit shown by those telling me their stories, and troubled by the question of forgiveness in a way I had never previously been in my life. If I was beginning to build up anger and prejudice against the Serbs who were committing these crimes, how could I, as a Christian, expect those who had actually suffered such evil to forgive? How could that be possible? How would a true peace ever be born here again?

Sometimes we would drive on east of Zagreb, navigating unsigned tracks (the old motorway had been shelled) to the city of Slavonski Brod. It lay on the banks of the River Sava, which separates Croatia from Bosnia-Herzegovina, and was being shelled and sniped at from across the slow-moving waters. The road bridges lay snapped in half in the river and all the buildings closest to its banks had planks of timber propped up to cover every window and door. After carefully unloading our food to a long line of people, who had been invited to queue at the back of our truck clutching one empty plastic carrier bag each (a self-imposed, practical way to ration their share), we were offered accommodation in a little house on a hill above the town, currently occupied by an elderly couple who were refugees from northern Bosnia-Herzegovina. Our dinner was eaten in awkward silence as all earlier attempts at communication had ended in failure (their English was even worse than our Serbo-Croat). But, afterwards, our host Mladen and I sat outside drinking Slivovitz, and after a few glasses we somehow found we began to understand each other a little. He explained to me that his house lay on the plain that we could see stretching into the distance on the other side of the river. It would now be occupied by Serbs. He had owned a little land and a few plum trees; in fact the Slivovitz we were drinking was made from their fruit. Before they finally fled, having already packed up all the belongings they could carry (including this Slivovitz), he took his axe and chopped down his precious plum trees. Some Serbs might now be living in his house but they wouldn’t be enjoying his plums. He laughed a loud bitter laugh at this point, trying to convince me, and perhaps himself too, that this was a funny story rather than one filled with burning hatred.

I began to dislike the terms ‘refugees’ or ‘displaced people’. Of course these are simply necessary, useful ways accurately to describe people who have fled their homes. But I realized that these terms, until I met the real people categorized that way, and got to know them, had begun to represent inaccurate stereotypes in my mind. In another Zagreb camp, during a conversation with a likeable, sparkly-eyed, articulate middle-aged man, I learnt that he had previously been the CEO of a haulage company with a large fleet of trucks. The fact that at that particular moment in time I was the one who happened to be driving a lorry and giving him aid, even though I had a poorer education, a much smaller experience of life and far less knowledge of how to organize the transportation of goods by truck, most certainly gave me no reason to feel in any way superior to him. Although I found it hard to admit, I had caught myself beginning to feel that way: I the giver; this stranger the receiver. I with power; he with none. I began to realize that this kind of work was a very dangerous one indeed.

Meanwhile, Marijo had found a new way to distribute our gifts of clothing to those in great need. He had come to realize that many found their newfound reliance on aid the greatest suffering of all. In order to respect their dignity, he would take over a hall or large space, and lay out the clothing on long rows of tables. He would then advertise an invitation for people to come and choose whatever they wished ‘so they could give to people they might know in great need’. Thus he found a way for people to come and select the clothing they needed and liked without public humiliation.

And so it went on, truckload after truckload, filled with an ever-growing torrent of donations from Scotland. Julie, to my delight, had indeed decided to continue helping and was now my co-driver on most journeys. As the volume of support increased it became clear to us that a very small truck was not the most cost-effective way to be transporting large quantities of goods over long distances. We needed something larger. To be able to drive the largest trucks we had to sit our Heavy Goods Vehicle driving test and so, during November of 1993, we stayed with Julie’s family in Inverness (who had been among the greatest supporters of our work before I had even met Julie) and began to take the necessary lessons. To my great discomfort, after a couple of lessons together, it became rather obvious that Julie was much better than I was at driving an articulated truck. In fact, after the first ‘lesson’ with Julie at the wheel, the instructor said to her in an incredulous tone, ‘You are kidding me on, aren’t you? You’re not a beginner, you’ve been driving these things before, haven’t you?’ My heart sank a little and I climbed into the driver’s seat for my turn.

‘You might need a little bit more work,’ he stated tactfully at the end of my drive, ‘especially on the roundabouts.’

This was kind of him given the drastic measures at least one car driver had taken to avoid being squashed by my trailer. I had not previously understood all that needs to be considered while driving a 16-metre vehicle that bends when you go round corners. At his kind words, a little knot of fear formed in my stomach and over the next couple of weeks this became something closer to panic. It was not so much thoughts of crushing a fellow roundabout user, or even demolishing a petrol station with one clumsy swish of my enormous tail, which caused me this anxiety. It was, rather, the prospect of having to tell my friends back in Dalmally the news that Julie had passed the test and I hadn’t. This would provide them with ammunition for jokes at my expense for years to come.

And indeed it has, for in the end Julie did pass her test with flying colours and I failed (yes, my trailer had strayed into another lane while negotiating a roundabout). My excuse that I was starting with a disadvantage, having passed my original driving test in an old Land Rover, in our neighbouring village of Inveraray – a village entirely bereft of roundabouts – did not wash with any of them. To my enormous relief I passed at the second attempt, and before long we had bought a huge 44-tonne articulated truck. Julie had a habit of naming all our trucks and for some reason, which I never understood, she called this one ‘Mary’, the most unlikely name I could imagine for this gigantic beast. We were delighted to discover just how much aid we could fit inside this truck, all the more so when we were suddenly immersed in a bigger wave of donations from the public than ever before.

For several months we had been closely following the disturbing events unfolding in Srebrenica. Another Muslim town in a Serbian-controlled area of Bosnia-Herzegovina, it was now surrounded by enemy forces and hugely overcrowded. Like several other towns in similar situations it had been declared a ‘safe haven’ by the UN, who promised they would ensure the safety of all those who sought refuge there. By July 1995, over 30,000 Muslims were crowded into what had previously been a tiny town in a small steep-sided valley. Each building was full of people and thousands slept outside. As the months wore on many began to die of starvation, while even more were killed by the shells being fired from the mountains above the town. Finally, while we and many in the world watched in disbelief and horror, the Serb soldiers invaded the town. The 400 Dutch UN soldiers surrendered without firing a shot. The Serbs then proceeded to select all the Muslim men of fighting age, took them to an abandoned factory and murdered over 8,000 of them in two days. Most of the women (after many had been raped) and children were left to flee through the forests. The majority of them made their way to Tuzla, the nearest large town, where a makeshift camp of tents was hastily erected at an old airfield. All of this unfolded before the eyes of the world. We were kept up to date by regular bulletins. In addition to the anger I felt at the Serbs, I now experienced a burning rage at the UN and our own government, who had simply let this pre-planned atrocity happen in a place they had the audacity to call a ‘safe haven’. I felt ashamed.

Immediately after this event donations poured in faster than ever, both from an outraged public and food companies who offered us pallets of flour, sugar, canned foods and much more. And so, with an enormous, precious cargo, we set off in our new articulated lorry, determined to get this aid to the women and children recently arrived in Tuzla – not a straightforward task given the only way to reach that town would be to cross central Bosnia-Herzegovina where the war was still raging in a complicated way. We knew our large truck was not designed for the mountain tracks that we would need to navigate and so we agreed to collaborate with another UK charity, which was using small trucks to deliver aid within Bosnia-Herzegovina.

We met them in the Croatian town of Split and, in an industrial complex, we decanted our load into their five trucks, under a searing sun. After a much-needed dip in the Adriatic we headed north, Julie and I now co-driving the smaller trucks with our new colleagues. By the second day of driving we had left behind the tarmac for safer dirt tracks in the forest. These felt familiar to me as they were similar to roads in Scotland on which I had learnt to drive as a teenager. And the surrounding landscape was familiar, too, although the mountains were a bit taller and more dramatic than those in Argyll. But I soon began to realize that these trucks, unlike the Land Rovers and pickups I was used to, were not four-wheel-drive vehicles and were clearly not designed for this terrain. The roads became rougher and steeper. Wheels began to spin and I started to worry. And my growing concern was not just caused by the unsuitable vehicles we had found ourselves in, but by a realization that among the new team we were now part of some appeared more interested in thrill-seeking than the safe delivery of aid. Just north of the city of Mostar we had seen and heard shells exploding in the distance. I was horrified to hear one of our co-drivers suggest we take a route closer to where the smoke was still rising so we ‘could see what was going on’. It appeared to me as if some of them wanted to play at being soldiers. When we stopped at UN bases to gain advice on the safest routes to proceed on, some of our co-drivers persuaded the soldiers to lend them their machine guns so they could pose for photographs.

I began to understand for the first time why the larger aid agencies often saw some smaller charities’ efforts as amateurish and dangerous. As we all settled down for the night to sleep outside, beside our row of parked trucks, Julie and I quietly discussed our misgivings about working with these people, but we realized that right now, having reached a part of central Bosnia-Herzegovina that neither of us knew, we had no real option but to go on with them towards Tuzla. And besides, we needed to tell all the donors back home that we had seen their donations arrive safely. I climbed into my sleeping bag in a bad mood. Our co-workers had not even brought decent supplies for us to eat, and going to bed hungry never failed to make me self-piteous. During the night, we awoke to find a pack of wild dogs running over us. It was the weirdest sensation. They scampered over our sleeping bags, apparently disinterested in us, and disappeared into the pitch-black. I wondered what had happened to their owners and what they were running from or to.