скачать книгу бесплатно

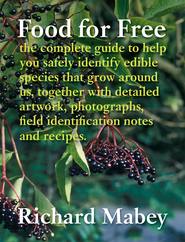

Food for Free

Richard Mabey

The classic foraging guide to over 200 types of food that can be gathered and picked in the wild, Food for Free returns in its 40th year as a sumptuous, beautifully illustrated and fully updated anniversary edition.Originally published in 1972, Richard Mabey’s classic foraging guide has never been out of print since. Food for Free is a complete guide to help you safely identify edible species that grow around us, together with detailed artwork, field identification notes and recipes.In this stunning 40th anniversary edition, Richard Mabey’s fully-revised text is accompanied by photographs, new recipes and a wealth of practical information on identifying, collecting, cooking and preparing, history and folklore. Informatively written, beautifully illustrated and produced in a new, larger format, Food for Free will inspire us to be more self-sufficient and make use of the natural resources around us to enhance our lives.

© Justus de Cuveland/Imagebroker/FLPA

© Siepmann/Imagebroker/FLPA

Preface to the new edition

In 2010, René Redzepi’s Copenhagen restaurant Noma, whose reputation rests on its innovative use of an extraordinary range of wild ingredients, was judged to be the best eatery in the world in an annual poll of food professionals. It was a milestone in the foraging renaissance, but also a sign of the times. It would be hard to find a serious restaurant these days that doesn’t feature wild food on its menu. Marsh samphire, chanterelles, wild garlic, dandelion leaves, elderberries, have all become routine ingredients. And increasingly wildings are marshalled into the exotic presentations of the new cuisine. Snails on moss. Haws conjured into ketchup. Cep cappuccino. Sea-buckthorn-berry gel. A whole infrastructure of professional pickers has evolved to service the fashion, and portfolios of television series to popularize it. Wild food has gone mainstream.

How times have changed. When the first edition of Food for Free was published in 1972, foraging was still regarded as mildly eccentric. To the extent that it was a new (or revived) tradition, it seemed part of the counter-culture, not the food business. It was a natural outgrowth of the idealism of the 60s, and its roots were firmly anchored in the burgeoning interests in ecology and food quality. I have a snapshot of myself taken around the time the book was published. I’m sitting cross-legged on the lawn in a kaftan, looking rather smug, and cradling an immense puffball on my lap. What the picture reminds me of, forty years on, is that foraging for wild food then didn’t feel much like an exploration of some ancient rural heritage (though of course it was). It felt political, cheeky, hedge-wise, a poke in the eye for domesticity as much as domestication. It was only later that I began to appreciate that it might also be a way – on all kinds of social and cultural and psychological levels – of ‘reconnecting with the wild’.

But if you were to look at it sceptically, the growing popularity of wild food could seem like a shift in the opposite direction, not so much connecting ourselves with the wild, as domesticating the feral. The seriously intellectual Oxford Food Symposium devoted its annual conference to wild food in 2004. There were learned papers on foraging customs in south-west France and on ‘Wild food in the Talmud’, and a tasting of ‘The feral oils of Australia’. Here in the UK local authorities lay on guided forays in their country parks. New Forest fungi are on sale in supermarkets. The seeds of wild vegetables such as alexanders are available commercially, so you can germinate the wilderness in a window box. The fashionable rise of wild foods is perfectly expressed by the changing fortunes of marsh samphire. In the 60s it was an arcane seashore delicacy, a ‘poor man’s asparagus’. In 1981 it was served at Charles and Diana’s wedding breakfast, gathered fresh from the Crown’s own marshes at Sandringham. In the new millennium it’s become a garnish for restaurant fish, and a favourite seaside holiday souvenir, sold by the bag to those who don’t want to get their own legs mud-plastered, and as a bar-top snack, lightly vinegar-ed and set in bowls next to the crisps and peanuts. Out in the market-place the spirit of the hunter-gatherer seems to be waning.

© Paul Hobson/FLPA

© ImageBroker/Imagebroker/FLPA

But out in the countryside it is alive and well, and this strange duality – of atavistic foraging coexisting with comfortable eating-out – forces the question why? Why should 21st century diners, with most of the taste sensations on the planet effortlessly available to them on a plate, occasionally choose to browse about like Palaeolithics? What are we after? We’re opting for the most part for inconvenience food, for bramble-scrabbling, mud-larking, tree-climbing. For the painful business of peeling horse-radish and de-husking chestnuts., and the dutiful munching – for historic interest, of course – of the frankly rank ground elder, just because it was bought here as a pot-herb two thousand years ago. It seems a far cry from the duty once spelt out by that Edward Hyams, doyen of plant domestication, ‘to leave the fruits of the earth finer than he found them’.

But the inconvenience, the raw uncensored tastes, the necessity of getting physical with the landscape, may be the whole point. The gratifying discomfort of hunting down food the hard way seems genuinely to infuse its savour – even when someone else has done the gathering. As Henry David Thoreau wrote in Wild Fruit (1859): ‘The bitter-sweet of a white-oak acorn which you nibble in a bleak November walk over the tawny earth is more to me than a slice of imported pine-apple’. Another American forager called this elusive quality ‘gatheredness’.

To judge from the hundreds of letters I’ve been sent over the years, readers understand this. The intimacy with nature that foraging involves isn’t seen as pretend primitivism or some misty-eyed nostalgia for the simple life. Rather, it has encouraged a growing awareness of how food fits into the whole living scheme of things, and a curiosity and inventiveness that are every bit as sharp as those of our ancestors. Readers were writing about wild raspberry vinegar long before it became a fashionable ingredient of nouvelle cuisine; about the secret sites and local names of the little wild damsons that grow on the Essex borders; about childhood feasts of seaweed ‘boiled in burn water and laid on dog roses to dry’. Foreign cuisines, in which wild plants have always been important ingredients, have been brought to bear on our native wildings, and there have been experiments with fruit liqueurs that go way beyond sloe gin: service berries in malt whiskey, cloudberries in aquavit, gin with extra juniper berries.

Some of this innovativeness is even permeating the commercial food trade. A Glasgow brewery uses Argyllshire heather tops to flavour a popular ale sold as ‘leann fraoch’. Nettle leaves wrap Cornish ‘Harg’ cheese and sloe gins are available in the supermarkets. But it’s the new breed of adventurous chefs who are pushing at the boundaries of wild food use and bringing new ingredients into the repertoire, plants (or bits of plants) that may have never been deliberately eaten before: sea-aster (now cultivated commercially), bush vetch, flower pollens (with egg), spruce shoots, hogweed seeds (surprisingly like caradamom).

There has, of course, been a backlash. Some landowners and conservationists are worried that the sheer volume of foraging – especially where it is done professionally for the restaurant trade – may be damaging the populations of wild species: Marsh samphire, for instance, a major wild crop along the north Norfolk coast, but also an important stabiliser of bare mud on unstable shorelines. This is usually yanked straight out of the ground by foragers, root and all, so that the plant (an annual dependent on seeding) is destroyed. But whether samphire gathering, an ancient tradition in this region, happens on a sufficient scale to cause real damage and is therefore in need of controlling is debatable.

It’s mushrooming that raises the most serious worries. In a few areas, the widespread picking of fungi, including quite scarce species like cauliflower fungus, has become intense, and amplified by commercial foraging teams. In favoured spots, such as the New Forest and Burnham Beeches, there are now bye-laws prohibiting picking altogether, though this is a contentious matter, since the picked mushroom is merely a fruiting body, not the fungus ‘plant’ itself.

For myself, I’m not overly worried about the conservation impact of foraging. Almost all orthodox wild foods – leaves, nuts, fruits, even mushrooms – are a renewable resource, and are shed naturally by plants. And the impact of picking on wild vegetation is negligible when you compare it with the destructive effects of modern agriculture. But foraging has other, more subtle, side effects. It competes with the food gathering of wild birds and mammals. In some places it can make a visible impression on the local landscape, and spoil the enjoyment of walkers and naturalists. What we need more than legislation, I believe, is a foraging etiquette, to regulate our gathering enthusiasms in keeping with the needs of other organisms in the ecosystem (non-foraging humans included).

Paradoxically, it may be the restaurants that are doing most to develop this. The new wild food recipes use minute quantities of their ingredients. The ways in which they are cooked – frosted, blanched, quick-pickled, for instance – are designed to bring out the intensity of flavour, that ‘bitter sweet’ of the gathered wilding that Thoreau rhapsodised over. And chefs like René Redzepi are conjuring whole miniature ecosystems in their dishes. One of Noma’s set-pieces is ‘Blueberries surrounded by their natural environment’, an extraordinary evocation of an autumn heathland, with balls of spruce and bilberry ice-creams nestling in a cooled salad of wood sorrel and heather tops. It might be overstating things to call dishes like this works of art. But they have the same intentions as art, to encourage us to experience and think about the astonishing variety and texture of the wild, not to satisfy our hunger. And so they are able to employ the smallest quantities of their foraged ingredients.

I find I’ve drifted this way myself, evolving into a wayside nibbler. I like lucky finds, small wayside gourmet treats. I relish the shock of the new taste, that first bite of an unfamiliar fruit. Sun-dried English prunes, from a damson bush strimmed while it was in fruit. Single wild blackcurrants picked from a boat. Reed-stems, sucked for their sugary sap. Often the catch is apples, wayside wildings sprung from thrown-away cores and bird droppings. They seem to catch everything that’s exhilarating about foraging: a sharpness of taste, and of spirit; an echo of the vast, and mostly lost, genetic diversity of cultivated fruits; a sense of place and season. I’ve found apples that tasted of pears, fizzed like sherbet, smelt of quince, and still dream of discovering the lost Reinette Grise de St. Ogne with its legendary fennel savour. But it’s the finding of them, the intimacy with the trees and the places they grow, a heightened consciousness of what they need to survive, that are just as important. And it’s maybe that growing sense of intimacy amongst the new foragers that will provide the feedback to conserve their resource: ‘if you don’t take care of it you lose it.’ For me, it has generated the rough ethic, or etiquette, of scavenging. For preference I work the margins now, look for windfalls, vegetable road-kills, sudden flushes, leftovers. Or just those small, serendipitous treats off the bush. The 1930s fruit gourmet Edward Bunyan, meandering through his gooseberry patch, described the pleasures of ‘ambulant consumption’: ‘The freedom of the bush should be given to all visitors’. The freedom of the bush: it’s a liberty we should all enjoy, but also treasure.

This 40th anniversary edition includes many new recipes, including some based on ideas from René Redzepi, Sam and Sam Moro, and my old friend and fellow-forager Duncan Mackay. But I have not tinkered with the core of the text, despite its youthful and sometimes naïve idealism. That, after all, is what sparked the book off. If there are moments of, shall we say, tastelessness as a result, then the responsibility is entirely mine.

Richard Mabey, Norfolk 2012

© Nicholas and Sherry Lu Aldridge/FLPA

Introduction

It is easy to forget, as one stands before the modern supermarket shelf, that every single one of the world’s vegetable foods was once a wild plant. What we buy and eat today is still essentially nothing more special than the results of generations of plant-breeding experiments. For most of human history these were directed towards improving size and cropping ability. Some were concerned with flavour and texture – but these are fickle qualities, dependent for their popularity as much on fashion as on any inherent virtue. In later years there have been more ominous moves towards improving colour and shape, and most recently we have seen developments such as genetically modified crop plants and irradiated food, raising worries not only about human health but also about the potentially harmful effects of modern farming methods on the environment.

Indeed, concerns over modern methods of food production have led to something of a backlash, and Michelin-starred chefs are advocating the joys of marsh samphire, a native coastal plant that goes beautifully with another native wild food, fish. For the rest of us likewise: if plant breeding has been directed towards the introduction of bland, inoffensive flavours, and has sacrificed much for the sake of convenience, those old robust tastes, the curly roots and fiddlesome leaves, are still there for the enjoyment of those who care to seek them out.

To some extent, we have become conditioned by the shrink-wrapped, perfectly shaped produce we find in our supermarkets, and we are reluctant to venture into woods, pastures, cliff-tops and marshlands in search of food. But in fact almost every British garden vegetable (greenhouse species excepted) still has a wild ancestor flourishing here. Wild cabbages grow along the south coast, celery along the east. Wild parsnips flourish on waste ground everywhere. Historically these have always been sources of food in times of scarcity, yet each time with less ingenuity and confidence, less native knowledge about what they are and how they can be used. Food for Free is about these plants, and how they once were and can still be used as food. It is a practical book, I hope, though it would be foolish to pretend that there are any pressing economic reasons why we should have a large-scale revival of wild food use. You would need to be a most determined picker to keep yourself alive on wild vegetables, and since they are so easy to cultivate there would be very little point in trying. Nor are wild fruits and vegetables necessarily more healthy and nutritious than cultivated varieties – though some are, and most of them are likely to be comparatively free of herbicides and other agricultural poisons.

Why bother, then? Why not leave wild food utterly to the birds and slugs? My initial pleas are, I’m afraid, almost purely sensual and indulgent: interest, experience, and even, on a small scale, adventure. The history of wild food use is interesting enough in its own right, and those who would never dream of grubbing about on a damp woodland floor for their supper may still find themselves impressed by our ancestors’ resourcefulness. But those who are prepared to venture out will find more substantial rewards. It is the flavours and textures that will surprise the most, I think, and the realisation of to just what extent the cultivation and mass production of food have muted our taste experiences. There is a whole galaxy of powerful and surprising flavours preserved intact in the wild stock that are quite untapped in cultivated foods: tart and smoky berries, aromatic fungi, crisp and succulent shoreline plants. There is much along these lines that could be said in favour of wild foods. Some of them are delicacies, many of them are still abundant, and all of them are free. They require none of the attention demanded by garden plants, and possess the additional attraction of having to be found. I think I would rate this as perhaps the most attractive single feature of wild food use. The satisfactions of cultivation are slow and measured. They are not at all like the excitement of raking through a rich bed of cockles, of suddenly discovering a clump of sweet cicely, of tracking down a bog myrtle by its smell alone. There is something akin to hunting here: the search, the gradually acquired wisdom about seasons and habitats, the satisfaction of having proved you can provide for yourself. What you find may make no more than an intriguing addition to your normal diet, but it was you that found it. And in coastal areas, in a good autumn, it could be a whole three-course meal.

Wild food and necessity

It is not easy to tell how wide a range of plants was eaten before agriculture began. The seeds of any number of species have been found in Neolithic settlements, but these may have already been under a primitive system of cultivation. Plants gathered from the wild would inevitably drop their seed and begin to grow near their pickers’ dwellings; and if, as was likely, the specimens collected were above average in size or yield, so might be their offspring. So a sort of automatic selection would have taken place, with crops of the more fruitful plants growing naturally near habitation.

By the Elizabethan era, the range of wild plants and herbs used and understood by the average cottager was wide and impressive. In many ways it had to be. There was no other source of readily available medicine, or of many fruits and vegetables. Yet even under conditions of necessity, how is one to explain the discovery that as cryptic a part as the styles of the saffron crocus was useful as a spice? The number of wild bits and pieces that must have been put to the test in the kitchen at one time or another is hair-raising. We should be thankful the job has been done for us.

© Mark Sisson/FLPA

Many plants passed into use as food at this time as a by-product of their medicinal use. Blackcurrants, for instance, were certainly used for throat lotions before the recipients realised they were also quite pleasant to eat when you were well. Sheer economy also played a part, as in finding a use for hop tops that had to be thinned out in the spring. But like so much else, these old skills and customs were eroded by industrialisation and the drift to the towns. The process was especially thorough in the case of wild foods because cultivation brought genuine advances in quality and abundance. But if the knowledge of how to use them was fading, the plants themselves continued to thrive. Most of them prospered as they had always done in woods and hedgerows. Those that flourished best in the human habitats bided their time under fields which had been turned over to cultivation, or moved into the new wasteland habitats that were a by-product of urbanisation. Plants which had been introduced as pot-herbs clung on at the edges of gardens, as persistent as weeds as they were once abundant as vegetables.

Then some crisis would strike the conventional food supplies, and people would be thankful for this persistence. On the island fringes of Britain, where the ground is poor and the weather unpredictably hostile, the tough native plants were the only invariably successful crops. The knowledge of how to use these plants as emergency rations was kept right up to the time air transport provided a reliable lifeline to the mainland.

It was the two World Wars, and the disruptions of food supplies that accompanied them, which provided one of the most striking examples of the usefulness of wild foods. All over occupied Europe fungi were gathered from woods, and wild greens from bomb sites. In America, pilots were given instructions on how to live off the wild in case their planes were ditched over land. And in this country, the government encouraged the ‘hedgerow harvest’ (as they called one of their publications) as much as the growing of carrots.

Wild plants are invaluable during times of famine or crisis, precisely because they are wild. They are quickly available, tough, resilient, resistant to disease, adapted to the climate and soil conditions. If they were not, they would have simply failed to survive. They are always there, waiting for their moment, thriving under conditions that our pampered cultivated plants would find intolerable.

Some modern agriculturalists are beginning to look seriously at the special qualities of wild food plants. Conventional agriculture works by taking an end food product as given, and modifying plants and conditions of growth to produce it as efficiently as possible. In regions that are vastly different from the plant’s natural environment, its survival is always precarious, and often at damaging expense to the soil and the natural environment. The alternative approach is to study the plants that grow naturally and luxuriantly in the area, and see what possible food products can be obtained from them. This should become an especially fruitful line of research in developing countries with poor soils.

Plant use and conservation

These last few instances are examples of conditions in which wild food use was anything but a frivolous pastime. I sincerely hope that this book will never be needed as a manual for that sort of situation. But is there really nothing more to gathering wild foods than the fun of the hunt, and the promise of some exotic new flavours? I think there is. Getting to know these plants and the uses that have been made of them is to begin to understand a whole section of our social history. The plants are a museum in themselves, hangovers from times when palates were less fastidious, living records of famines and changing fashions and even whole peoples. To know their history is to understand how intricately food is bound up with the whole pattern of our social lives. It is easy to forget this by the supermarket shelf, where the food is instantly and effortlessly available, and soil and labour seem part of another existence. We take our food for granted as we do our air and water, and all three are threatened as a result.

Yet familiarity with the ways of just a few of the plants in this book gives an insight at first hand into the complex and delicate relationships which plants have with their environment: their dependence on birds to carry their seeds, on animals to crop the grass that shuts out their light, on wind and sunshine and the balance of chemicals in the soil, and ultimately on our own good grace as to whether they survive at all. It is on the products, wild or cultivated, of this intricate network of forces that our food resources depend.

I know there may be some people who will object to this book on the grounds that it may encourage further depletions of our dwindling wildlife. I believe that the exact opposite is true. One of the major problems in conservation today is not how to keep people insulated from nature but how to help them engage more closely with it, so that they can appreciate its value and vulnerability, and the way its needs can be reconciled with those of humans. One of the most complex and intimate relationships which most of us can have with the natural environment is to eat it. I hope I am not overstating my case when I say that to follow this relationship through personally, from the search to the cooking pot, is a more practical lesson than most in the economics of the natural world. Far from encouraging rural vandalism, it helps deepen respect for the interdependence of all living things. At the very least it will provide a strong motive for looking after particular species and maybe individual ecosystems.

And maybe foraging can contribute even more, in today’s ecologically threatened world. If plants like wilding apples could contribute to the restoration of lost cultivated varieties, maybe, conversely, the restoration of cultivated land to wild, forageable land could build up new natural ecosystems. The possibility of the revival of a gentle communal use of such places would add foraging to the increasing range of community food initiatives, from organic food boxes to city farms.

Omissions

This book covers the majority of wild plant food products which can be obtained in the British Isles. But there are some categories which I have deliberately omitted.

• There is nothing on grasses and cereals. This is intended to be a practical book, and no one is going to spend their time hand-gathering enough wild seeds to make flour.

• I have touched briefly on the traditional herbal uses of many plants where this is relevant or interesting. But I have included no plants purely on the grounds of their presumed therapeutic value. This is a book about food, not medicine.

• This is also a book about wild plant foods, which is the simple reason (apart from personal qualms) why there is nothing about fish and wildfowl.

• But I have included shellfish because, from a picker’s perspective, they are more like plants than animals. They stay more or less in one place, and are gathered, not caught.

Layout of the book

The text is divided into sections covering (1) edible plants (trees and herbaceous plants), (2) fungi, lichens and one fern, (3) seaweeds, (4) shellfish. Within each category, species are arranged in systematic order.

Some picking rules

I have given more detailed notes on gathering techniques in the introductions to the individual sections (particularly fungi, seaweeds and shellfish). But there are some general rules which apply to all wild food. Following these rules will help to guarantee the quality of what you are picking, and the health of the plant, fungus or shellfish population that is providing it.

Although we have tried to make both text and illustrations as helpful as possible in identifying the different plant products described in this book, they should not be regarded as a substitute for a comprehensive field guide. They will help you decide what to gather, but until you are experienced it is wise to double-check everything (particularly fungi) in a book devoted solely to identification. Conversely, never rely on illustrations alone as a guide to edibility. Some of the plants illustrated here need the special preparation described in the text before they are palatable.

But although it is obviously crucial to know what you are picking, don’t become obsessed about the possible dangers of poisoning. This is a natural worry when you are trying wild foods for the first time, but happily a groundless one. As you will see from the text there are relatively few common poisonous plants and fungi in Britain compared with the total number of plant species.

To put the dangers of wild foods into perspective it is worth considering the trials attendant on eating the cultivated foods we stuff into our mouths without question. Forgetting for a moment the perennial problems of additives and insecticide residues, and the new worries about irradiated and genetically modified food, how many people know that, in excess, cabbage can cause goitre and onions induce anaemia? That as little as one whole nutmeg can bring on days of hallucinations? Almost any food substance can occasionally bring on an allergic reaction in a susceptible subject, and oysters and strawberries, as well as nuts of all types, have particularly infamous reputations in this respect. But all these effects are rare. The point is that they are part of the hazards of eating itself, rather than of a particular category of food.

Here are some basic rules to ensure your safety when gathering and using wild foods:

• Make sure you correctly identify the plant, fungus or seaweed you are gathering.

• Do not gather any sort of produce from areas that may have been sprayed with insecticide or weedkiller.

• Avoid, too, the verges of heavily used roads, where the plant may have been contaminated by car exhausts. There are plenty of environments that are likely to be comparatively free of all types of contamination: commons, woods, the hedges along footpaths, etc. Even in a small garden you are likely to be able to find something like twenty of the species described in this book.

© David Hosking/FLPA

• Wherever possible use a flat open basket to gather your produce, to avoid squashing. If you are caught without a basket, and do not mind being folksy, pin together some dock or burdock leaves with thorns.

• When you have got the crop home, wash it well and sort out any old or decayed parts.

• To be doubly sure, it is as well to try fairly small portions of new foods the first time you eat them, just to ensure that you are not sensitive to them.

Having considered your own survival, consider the plant’s:

• Never strip a plant of leaves, berries, or whatever part you are picking. Take small quantities from each specimen, so that its appearance and health are not affected. It helps to use a knife or scissors (except with fungi (#litres_trial_promo)).

• Never take the flowers or seeds of annual plants; they rely on them for survival.

• Do not take more than you need for your own needs.

• Be careful not to damage other vegetation or surrounding habitat when gathering wild food.

• Adhere at all times to the Code of Conduct for the conservation and enjoyment of wild plants, published by the Botanical Society of the British Isles (www.bsbi.org.uk/Code.htm).

What the law says

The law concerning foraging is comparatively straightforward, at least on the surface.

• You are allowed to gather and take away the four Fs – foliage, flowers, fruit, fungi – of clearly WILD plants, e.g. blackberries and elderflowers, even on private land, though other laws regarding trespass and criminal damage may restrict you. You are not entitled to harvest anything from CULTIVATED crop-plants, e.g orchard trees or field-peas.

• But under the Wildlife and Countryside Act and the Theft Act you may not SELL wild produce gathered in this way.

• Nor may you UPROOT any wild plant without the permission of the owner of the land on which it is growing.

• A few very RARE plants (none of those mentioned in this book) are protected by law from any kind of picking.

• On various areas of land otherwise open to the public – certain forests, commons, parks, and the new Open Access areas declared under the Countryside and Rights of Way Act, 2000 (CROW) – there are BY-LAWS prohibiting any kind of picking. These are usually spelt out on notice boards.

But there are cases which don’t fall into these clear extremes, about which the law is hazy. For example, nuts from a walnut tree overhanging a pavement are clearly the owner’s whilst they are on the tree. But how about those that have fallen onto the public right of way? And how, on a road embankment, can a planted apple-tree be distinguished from a self-sown wilding? In all such matters, and others where the law is ambiguous, use your common sense, and don’t be perpetually looking over your shoulder.

Edible plants

Roots

Roots are probably the least practical of all wild vegetables. Firstly, few species form thick, fleshy roots in the wild, and the coarse, wiry roots of – for instance – horse-radish and wild parsnip are really only suitable for flavouring. Second, under the Wildlife and Countryside Act it is illegal to dig up wild plants by the root, except on your own land, or with the permission of the landowner.

The few species that are subsequently recommended as roots are all very common and likely to crop up as garden weeds. Where palatable roots of a practical size and texture can be found, however, they are quite versatile, and may be used in the preparation of broths (herb-bennet), vegetable dishes (large-flowered evening-primrose), salads (oxeye daisy), or even drinks (chicory, dandelion).

Green vegetables

The main problem with wild leaf vegetables is their size. Not many wild plants have the big, floppy leaves for which cultivated greens have been bred, and as a result picking enough for a serving can be a long and irksome task. For this reason the optimum picking time for most leaf vegetables is probably their middle-age, when the flowers are out and the plant is easy to recognise, and the leaves have reached maximum size without beginning to wither.

Green vegetables can be roughly divided into three types: salads, cooked greens, and stems. For general recipes see dandelion for salads, sea beet or fat-hen (#litres_trial_promo) for greens, and alexanders for stems.

All green vegetables can also be made into soup (see sorrel), blended into green sauces, or made into a pottage or ‘mess of greens’ by cooking a number of species together.

Herbs

A herb is generally defined as a leafy plant used not as a food in its own right but as a flavouring for other foods, and most herbs tend to be milder in the wild state than under domestication; being valued principally for their flavouring qualities, it is these which domestication has attempted to intensify, not delicacy, size, succulence or any of the other qualities that are sought after in staple vegetables. You will find, consequently, that with wild herbs you will need to double up the quantities you normally use of the cultivated variety.

The best time to pick a herb, especially for the purposes of drying, is just as it is coming into flower. This is the stage at which the plant’s nutrients and aromatic oils are still mainly concentrated in the leaves, yet it will have a few blossoms to assist with the identification. Gather your herbs in dry weather and preferably early in the morning before they have been exposed to too much sun. Wet herbs will tend to develop mildew during drying, and specimens picked after long exposure to strong sunshine will inevitably have lost some of their natural oils by evaporation.

Cut whole stalks of the herb with a knife or scissors to avoid damaging the parent plant. If you are going to use the herbs fresh, strip the leaves and flowers off the stalks as soon as you get them home. If you are going to dry them, leave the stalks intact as you have picked them. To maintain their colour and flavour they must be dried as quickly as possible but without too intense a heat. They therefore need a combination of gentle warmth and good ventilation. A kitchen or well-ventilated airing cupboard is ideal. The stalks can be hung up in loose bunches, or spread thinly on a sheet of paper and placed on the rack above the stove. Ideally, they should also be covered by muslin, to keep out flies and insects and, in the case of hanging bundles, to catch any leaves that start to crumble and fall as they dry. All herbs can be used to flavour vinegar, olive oil or drinks, as with thyme in aquavit.

Spices

Spices are the aromatic seeds of flowering plants. There are also a few roots (most notably horse-radish) that are generally regarded as spices.

Most plants which have aromatic leaves also have aromatic seeds, and can be usefully employed as flavourings. But a warning: do not expect the flavour of the two parts to be identical. They are often subtly different in ways that make it inadvisable simply to substitute seeds for leaves.

Seeds should always be allowed to dry on the plant. After flowering, annuals start to concentrate their food supplies into the seeds so that they have enough to survive through germination. This also, of course, increases the flavour and size of the seeds. When they are dry and ready to drop off the plant, their food content and flavour should be at a maximum.

Flowers

Gathering wild flowers for no other reason than their diverting flavours would at least be antisocial, and in the case of the rarest species it is illegal under the Wildlife and Countryside Act. Some of the flowers mentioned in this book are rare and should not be picked these days because of declining populations, though many of them have been anciently popular ingredients of salads, and are included for their historical interest.

The only species I advocate picking from are those where removing flowers in small quantities is unlikely to have much visual or biological effect. They are all common and hardy plants. They are all perennials and do not rely on seeding for continued survival. They are mostly bushes or shrubs in which each individual produces an abundant number of blossoms.

Most of the recipes in the book require no more than a handful or two of blossoms, but if you like the sound of any of them it may be best to grow the plants in your garden and pick the flowers there. Many species, such as cowslip and primrose, are commercially available as seed.

Fruits

A number of the fruits I have included are cultivated and used commercially as well as growing in the wild. Where this is the case I have not given much space to the more common kitchen uses, which can be found in any cookery book. I have concentrated instead on how to find and gather the wild varieties, and on the more unusual traditional recipes.

Almost all fruit, of course, can be used to make jellies and jams. Rather than repeat the relevant directions under each fruit, it is useful to go into some detail here. The notes below apply to all species.

Another process which can be applied to most of the harder-skinned fruits is drying. Choose slightly unripe fruit, wash well, and dry with a cloth. Then strew it out on a metal tray and place in a very low oven (50°C, 120°F). The fruit is dry when it yields no juice when squeezed between the fingers, but is not so far gone that it rattles. This usually takes between 4 and 6 hours.