Полная версия:

The Times Great Irish Lives: Obituaries of Ireland’s Finest

COPYRIGHT

Published by Times Books

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

Westerhill Road

Bishopbriggs

Glasgow G64 2QT

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Ebook First Edition 2016

© Times Newspapers Ltd 2016

www.thetimes.co.uk

Ebook Edition © September 2016

ISBN: 9780008222574, version 2016-10-13

The Times is a registered trademark of Times Newspapers Ltd

All rights reserved under International Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

The contents of this publication are believed correct. Nevertheless the publisher can accept no responsibility for errors or omissions, changes in the detail given or for any expense or loss thereby caused.

HarperCollins does not warrant that any website mentioned in this title will be provided uninterrupted, that any website will be error free, that defects will be corrected, or that the website or the server that makes it available are free of viruses or bugs. For full terms and conditions please refer to the site terms provided on the website.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

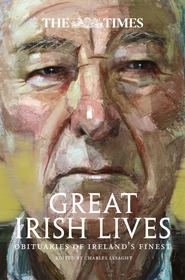

Cover Image:

“From Everywhere and Nowhere (Seamus Heaney)”

Colin Davidson b. 1968 © Colin Davidson. 2013 Collection Ulster Museum

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Henry Grattan

Daniel O’Connell

Maria Edgeworth

Tom Moore

Father Mathew

William Dargan

Earl of Rosse

Cardinal Cullen

Charles Stewart Parnell

Sir John Pope Hennessy

Mrs Cecil Alexander

Oscar Wilde

Lord Morris of Spiddal

Archbishop Croke

Michael Davitt

The O’Conor Don

Sir W. H. Russell

John Millington Synge

Sir Luke O’Connor

John Redmond

Cardinal Gibbons

Michael Collins

Erskine Childers

Thomas Crean V. C.

Lord Pirrie

Lord MacDonnell

Kevin O’Higgins

Countess Markievicz

John Devoy

John Woulfe Flanagan

T. P. O’Connor

Sir Horace Plunkett

Lady Gregory

George Moore

Edward Carson

William Butler Yeats

Sir John Lavery

James Joyce

Sarah Purser

John McCormack

Douglas Hyde

Edith Somerville

John Dulanty

Evie Hone

William Francis Casey

Margaret Burke Sheridan

Archbishop Gregg

Sean O’Casey

Jimmy O’Dea

William T. Cosgrave

Frank O’Connor

Lady Hanson

Sean Lemass

Lord Brookeborough

George O’Brien

Kate O’Brien

Eamon de Valera

John A. Costello

Brian Faulkner

Professor Frances Moran

Micheál Mac Liammóir

Professor F. S. L. Lyons

Anita Leslie

Frederick H. Boland

Siobhan McKenna

Eamonn Andrews

Sean MacBride

Samuel Beckett

Cardinal O Fiaich

Ernest Walton

Molly Keane

Michael O’Hehir

Dermot Morgan

Jack Lynch

Rev. F. X. Martin

Sister Genevieve O’Farrell

Maureen Potter

Mary Holland

Joe Cahill

Bob Tisdall

George Best

John McGahern

Charles Haughey

Sam Stephenson

David Ervine

Tommy Makem

Conor Cruise O’Brien

Vincent O’Brien

Alex “Hurricane” Higgins

Dr Garret FitzGerald

Declan Costello

The Knight of Glin

Mary Raftery

Aengus Fanning

Louis Le Brocquy

Maire MacSwiney Brugha

Maeve Binchy

Seamus Heaney

Albert Reynolds

The Rev. Ian Paisley

Jack Kyle

Brian Friel

Maureen O’Hara

Sir Terry Wogan

Searchable Terms

Footnotes

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

Charles Lysaght

WHEN DR JOHNSON proclaimed the Irish an honest race because they seldom spoke well of one another, he should have made it clear that it was the reputations of the living that he had in mind. In Ireland, speaking of the dead in the aftermath of their demise, the adage nihil nisi bonum applies not only among friends and acquaintances but in the media. Readers of Irish newspapers, national and especially local, are treated to accounts of the unprecedented gloom that settled over the district where the deceased lived, the largest and most representative gathering at a funeral within living memory, accompanied by eulogies reciting how the dear departed thought only of others and never of themselves, were never known to say an unkind word about anybody, were devoted to their family, were exemplary in their piety and charity and were universally loved and respected. Such undiscriminating eulogies lack credibility and do their subjects no favours.

It has been a signal service rendered by The Times to provide accounts of deceased Irish persons that aspire to more realism and more balance in their assessments while bringing out the exceptional achievements and positive qualities that make the deceased worthy of notice in a newspaper outside their own country. In the absence of a comprehensive dictionary of Irish biography they have sometimes been the best accounts of a person’s life, at least for a period, and, as such, a valuable reference for historians.

It has been helpful to this process that many of these obituaries are prepared in advance and so allow for checking facts and for reflection unaffected by the immediate surge of sympathy surrounding a death.

It is conducive to frankness that obituaries are published anonymously and that the identity of the authors will not be disclosed by the paper in their lifetime, so keeping faith with the nineteenth century description of The Times as ‘the most obstinately anonymous newspaper in the World’. It may add to the authority of a piece that it seems to represent the views of a great newspaper rather than an individual author. It probably puts some pressure on the individual authors to reflect a general view of a person rather than to indulge a personal experience or assessment.

Obituaries (especially major ones) may first be prepared when their subjects are relatively young and so need revision many times before publication. Apart from new facts, what is interesting about a person’s life can change quite rapidly. In the nature of things, the subject sometimes outlives the original author and what emerges on the final day is a composite work.

Historically, Irish obituaries in The Times reflected somewhat the troubled relationship that the paper had with Ireland from the days of Daniel O’Connell up to the creation of the independent Irish state. The difficulties in the relationship might even be traced back further to the incident when Irishman Barry O’Meara, who had been removed by the British Government from his role as physician to the captive Napoleon on St Helena, horse-whipped William Walter, mistaking him for his brother John who was one of the proprietors and the responsible editor of the paper. O’Meara had been affronted because The Times had dismissed as a lie a statement in his memoirs that he had been told by the deposed Emperor that The Times was in the pay of the exiled Bourbons. It ended up in court with O’Meara getting away with a fulsome apology.

The Times, under the editorship of Thomas Barnes (1817–41) supported O’Connell’s campaign for Catholic Emancipation. But their relationship with O’Connell went sour not long after he entered parliament in 1830 when he accused the paper of misreporting him. As he espoused the repeal of the Union and brought the ‘Romish clergy’ into politics, they denounced him as an unredeemed and unredeemable scoundrel and declared ‘war to the political extinction of one of us.’ One of the first assignments of the celebrated Irish-born reporter William Howard Russell was to report on O’Connell’s monster meetings in 1843 and on his subsequent trial and conviction in Dublin – it took over 24 hours to get the news of the verdict to London.

After O’Connell’s conviction had been set aside on appeal by the House of Lords, The Times returned to the fray, setting up what they called a commission in the form of a journalist sent to report on O’Connell’s treatment of his own tenants in Kerry. They were found to be living in poverty without a pane of glass in any of their windows. Russell was sent to Ireland again and, despite being on friendly terms with O’Connell, confirmed that this was indeed the case. O’Connell, for his part, denounced The Times as ‘a vile journal’ which had falsely, foully and wickedly calumniated him every day and on every subject. Against this background it is not surprising that his obituary in 1847 is critical and reflects a hostile political viewpoint. But its recognition of the positive qualities of what it called an ‘extraordinary man’ shows admirable balance. It claimed to have shown a forebearance of which O’Connell himself was incapable and to have treated indulgently the memory of a man who in a long lifetime seldom spared a fallen adversary.

The confrontation between nationalist Ireland and The Times reached its apotheosis in the late 1880s when The Times published a series of articles entitled ‘Parnellism and Crime’ that were, in fact, largely written by a young Irish Catholic barrister and journalist, educated under Jowett at Balliol, called John Woulfe Flanagan – although anonymously as was still customary for all articles. Parnell was accused of having been complicit with terrorism and the organized intimidation of the Land War. The allegations were subsequently supported by letters said to have been written by Parnell that were proved before a judicial commission to have been forged by one Richard Pigott. The unmasking of Pigott before the commission by Sir Charles Russell, a former Irish solicitor who was then the leader of the English Bar, was an historic set-piece much recalled in the annals of the law as well as politics. Less remembered is that the commission, on the strength of evidence given by the Fenian informer Henri Le Caron, upheld the substance of most of the charges made in the articles. The events cast a long shadow, well beyond the obituary published on Parnell’s death written by The Times’ leader writer E. D. J. Wilson where this was pointed out. An account of the episode in a volume of the History of The Times covering the years 1884 to 1912, published in 1947, led to corrigenda in an appendix in the next volume credited to Parnell’s surviving colleague and biographer Captain Henry Harrison MC. Attention was drawn to the role of Captain William O’Shea, the first husband of Mrs Parnell, as a witness before the commission and an admission made that the paper’s association with O’Shea proved by Captain Harrison ‘is not creditable’ and should not have been ignored in the History of The Times.

In his main address to the commission Sir Charles Russell had admitted the terrorism associated with the Land League but claimed that the root cause of it was English oppression and that the fomentor of discord between the two peoples through several generations had been The Times. Sir Henry James, who appeared for The Times, answered by citing a long list of critical occasions in Irish history when the paper had supported the Irish popular cause often at the risk of alienating dominant opinion in England. It had helped to secure Catholic emancipation; it had argued for the endowment of the Roman Catholic seminary at Maynooth and the disestablishment of the Irish Church; it had taken a leading part in the relief of distress during the Irish famine and advocated the extension of the Irish franchise; it had highlighted evictions and supported legislation giving greater protection to tenants.

Because of its opposition to nationalist aspirations The Times was berated in nationalist Ireland as the enemy of all things Irish. In fact, this was not so. The unionism of The Times was an inclusive unionism and did not spill over into a general antipathy to the Irish or even the Catholic Irish. Tom Moore, the poet, had been a regular and valued contributor. Edmund O’Donovan, the son of the great Gaelic scholar John O’Donovan and old Clongownian Frank Power were two Times journalists who perished with General Gordon reporting the Egyptian campaign of the 1880s.

In the obituaries columns, as elsewhere, the Irish of all backgrounds got a good show. Just occasionally there was some stereotyping, although it was not unfriendly. In 1891, remarking that in his qualities and talents as in his defects Sir John Pope Hennessy was a typical Irishman, his obituary depicted him as ‘quick of wit, ready in repartee, a fluent speaker, and an able debater but the enthusiasm and emotion which lent force and fire to his speeches led him into the adoption of extreme and impracticable views.’ A few years later the obituary of the colourful Irish judge Lord Morris of Spiddal contained the observation that ‘though an Irishman he was not given to verbosity.’ Of Michael Davitt, the Land Leaguer, it was remarked that ‘he was an Irishman of a somewhat unusual type dark and dour.’ A more extensive indulgence in stereotyping is to be found in the obituary of Charles Villiers Stanford, the composer (not included in this collection), who was, it was stated, ‘though an Irishman of the English occupation, every inch an Irishman; the quick acquisitive mind, the readiness of tongue, the appreciation of a good story and the power of telling it well, the ability to charm, and the love of a fight were qualities which endeared him to his friends but never left him in want of an enemy.’ It must be said that this kind of thing was relatively rare, whether because many Irish obituaries were written by fellow Irishmen or because of a fastidiousness among those responsible in the paper itself.

The pattern of supporting beneficial reforms for the Irish majority, while defending the Union and the maintenance of law and order, remained the policy of The Times into the twentieth century. It was predictable that the paper should support the executions of the leaders of the 1916 rebellion and of Roger Casement, who was not even accorded an obituary, which could have recorded the achievements that had led to his being knighted. The treatment of Casement was a formidable challenge to the impartiality of a number of British institutions.

Whatever about the reaction to the 1916 rebellion, The Times tended to reflect the general acceptance even among unionists in the wake of the temporarily suspended Home Rule Act of 1914 that there would have to be some form of self-government for Ireland after the War. Significantly, after the peace in 1918 and the replacement of Geoffrey Dawson as editor by Wickham Steed, The Times originated the scheme that eventually found expression in the Government of Ireland Act, 1920 with its home rule parliaments for Northern Ireland and what was called Southern Ireland. Prior to that, the Ulster unionist demand was to remain fully integrated in the United Kingdom and they were slow to see the opportunities the Government of Ireland Act was to offer for establishing a protestant state for a protestant people. The latter history of the Act as the charter for that state has tended to obscure the fact that it explicitly envisaged a future date of Irish union and created overarching institutions such as a Council of Ireland and an All-Ireland Court of Appeal out of which it was hoped that this union would grow. It was the rejection of it by nationalist leaders now bent on achieving a totally independent republic that deprived the Act of its unifying possibilities.

The rejection of the Government of Ireland Act by the Sinn Fein leadership and the ongoing assassinations of policemen led the Government to allow free rein to their security forces, the Black and Tans and the Auxiliary cadets. The Times joined in a crescendo of criticism of their disgraceful behaviour and was also highly critical of the hardline reaction of the Lloyd George government to the 74-day hunger strike to death in November 1920 of Terence MacSwiney, the Lord Mayor of Cork. Editorials argued for a settlement along the lines of that eventually agreed in December 1921 granting dominion status to Southern Ireland.

Significantly, when the leading Irish negotiators of that settlement, Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins, died in the early months of independence the obituaries were uncritical. In the case of Collins there was virtually no reference to his part in the campaign of assassination from 1919 to 1921 that had led to his being demonised in Britain before the settlement. The Times had a special reason for being grateful to him as he had applied his ruthless efficiency to securing the safe return of their special correspondent A. B. Kay, who was kidnapped by the IRA in January 1922.

An important influence on the editorial policy of The Times in these years was Captain Herbert Shaw, a Dubliner who had served in the Irish administration and was one of the secretaries to the Irish Convention of 1917–18 where the moderate elements of unionism and nationalism had tried to broker a settlement. It was Shaw who penned The Times editorial entitled ‘Playing the Game’ on the occasion of the opening of the Northern Ireland Parliament in 1921 by King George V that was influential in pushing the Government towards negotiations with the Sinn Fein leaders. He was the author of a number of notable obituaries on Irish figures of that period, some of which, such as that on William T. Cosgrave, did not appear until well after his own death in 1946. Others were written by Michael MacDonagh, the journalist champion and historian of the Irish Party, and the unionist John Healy, editor of the Irish Times, and Dublin correspondent of The Times from 1894 until 1934.

The creation of an independent state covering most of the island of Ireland did not diminish the coverage of Irish affairs in The Times. The Irish were still regarded as part of the broader British family, albeit that their political leaders seemed to want to loosen their ties with it. Even the neutrality in the Second World War did not alter this, perhaps because the Irish of every tradition were such a presence in the British war effort. Churchill spoke for many in Britain when at the end of the war, having criticised Irish neutrality and paid tribute to ‘the thousands of southern Irishmen who hastened to the battle-front to prove their ancient valour’, he expressed the hope that the two peoples would walk together in mutual comprehension and forgiveness.

However, in the quarter of a century after the Second World War Irish political life, both north and south of the border, ceased to command attention in the British media. Even then, a fair coverage of Irish subjects was maintained in The Times obituaries columns. There may have been a bias towards individuals and institutions that retained to some extent a broader British identity or made an impact in Britain and might be presumed to be of more interest to the readership but it did not preclude coverage of significant figures from other strands of Irish life, especially those from the literary and artistic community. The outbreak of violence in Northern Ireland around 1970 brought Ireland centre stage once more and this has been reflected in an even more comprehensive coverage of Irish subjects in the obituaries columns.

Meanwhile, in the course of the twentieth century, there had been significant developments in the paper in the organisation of obituaries loosening the connection of that part of the paper with those who formulated editorial policy. From 1920 there was a separate obituaries department with its own editor. While obituaries had been prepared in advance since the editorship of John Delane (1841–1877), Colin Watson, who was obituaries editor from 1956 to 1981, embarked on a policy of commissioning advance pieces on a wider variety of living subjects than had been the case previously. Very often, those commissioned to write them were not journalists or even professional writers. In general, they were recruited having regard to their knowledge of the subject rather than with an eye to providing a particular viewpoint. In the case of Irish subjects the authors were generally found in Ireland. So it is that more recent Irish obituaries have often not reflected an English viewpoint, let alone that inside The Times – although the authors, if they were doing their job, have been conscious, when writing, that their readership would be largely English.

Despite this general trend, unexpected deaths of notable figures have, on occasion, still thrown the obituaries department back on its own resources. So, when Brian Faulkner died unexpectedly in 1978, Colin Watson ran up a superb obituary that reflected the paper’s sympathy for Faulkner’s brave effort to lead a cross-community executive. Three years earlier in 1975 the death at an advanced age of Eamon de Valera, which cannot have been unexpected, was marked by a much praised obituary involving substantial insider input by the celebrated leader writer Owen Hickey into a piece prepared originally by the former editor of the Irish Times Alec Newman. Hickey, born in Ireland and, incidentally, a grandson of the novelist Canon Hanney (George Bermingham), was an invaluable source of knowledge and understanding about matters Irish for The Times throughout most of the second half of the twentieth century.

The lack of total identification between the editorial policy of the paper and the obituaries that evolved through the twentieth century was never better illustrated than in the case of Sean MacBride, who died in 1988. He had been commander-in-chief of the IRA in post-independence Ireland before becoming a government minister and finally a human rights activist honoured by being awarded both the Nobel and Lenin peace prizes. An obituary prepared by the present writer that was quite laudatory but not uncritical, was followed a couple of days later by an editorial headed ‘His infamous career’ berating him as a man who was to the end of his days a cosmopolitan high priest of the cult of violence directed at British victims.