Полная версия:

The Thorn of Lion City: A Memoir

LUCY LUM

The Thorn of Lion City

A MEMOIR

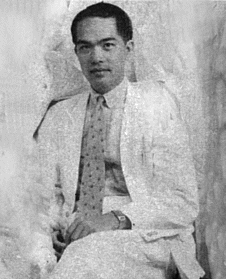

In memory of my father, Lum Poh-mun

Contents

Title Page Dedication Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter Thirteen Chapter Fourteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Sixteen Chapter Seventeen Chapter Eighteen Chapter Nineteen Chapter Twenty Chapter Twenty-One Chapter Twenty-Two Chapter Twenty-Three Chapter Twenty-Four Chapter Twenty-Five Chapter Twenty-Six Acknowledgements About the Author Copyright About the Publisher

One

‘Look at the red-haired devil’s air-raid shelter,’ Popo said, pointing to our neighbour’s garden. ‘How clever he is. So different from your father. It is like a house, their shelter, with camp beds and chairs, a wireless and lights. And so pretty outside, with tapioca, sugar cane and all those flowers.’

For weeks my grandmother Popo had told us that we were not to worry: the Japanese would never capture Singapore because the British would turn back the invaders. ‘Life will go on as normal,’ she said. But there were soldiers on every street, in the shops and the cinema. Every rickshaw had a soldier inside it. There were air-raid drills, and people dug in their gardens, building makeshift bomb shelters. You could tell how big a family was from the size of the mound of soil in the garden. Some of the shelters were like little foxholes, covered with wooden planks, branches and earth, but in our street the red-haired devil’s shelter was the biggest and best, and we were jealous. He was the English officer in charge of the police station where Father worked. His wife and children had been evacuated to England and he told Father that if the bombs came we could hide in his shelter with him and be safe.

Father said we did not need a hole under the earth to hide in. Instead he put the heavy teak table in the middle of the bedroom, then piled blankets and three kapok mattresses on top. He put more mattresses round the sides. He said these would stop the flying shrapnel and the ceiling crashing down on us. ‘If the bombs come, you won’t need to run outside to our neighbour’s garden. You can jump from your beds and curl up under the table. You must have fresh water and biscuits at the ready in your satchels,’ he said. ‘There will be no time to waste.’ When he talked to us about the bombs he was careful not to catch Popo’s or Mother’s eye. He was frightened of them. They did not like him telling them what to do.

My brothers, my sisters and I looked forward to the air-raid drills. We thought they were games. We five would grab our satchels, as Father had told us, race to the bedroom and dive under the table. It was dark and snug in there and we would play for hours. Sometimes Father would tell us stories about the island his family came from, Hainan, and we would listen and munch our biscuits.

I was seven, and no one explained anything to me. I was frightened of Popo too. Father told me that we should call her Waipo, Outside Grandmother, because she was our mother’s mother, not his. But if we called her Waipo she beat her chest and told us she would kill herself. ‘This old bag of bones has lived too long,’ she would say. ‘Even my grandchildren do not love me.’

One day I was brave: I asked Popo who the invaders were and why they wanted to attack Singapore. She went to a cupboard, pushed aside the piles of paper and the tiny red purses in which she kept the dried umbilical cords of her children and grandchildren, and pulled out a great map of the world. It was yellow with age and almost falling to pieces, but she spread it on the table in front of her.

‘Listen,’ she said, lowering herself into her favourite armchair. ‘My mother told me this story when I was a child. The mulberry tree is covered with rich and delicious leaves, which the silkworm likes. This is China,’ she said, pointing to a huge pink country on the map. ‘It is a country of plenty, like the mulberry tree with its leaves, but it is plagued by starving Japanese silkworms from across the sea.’ She rapped her knuckles on the islands of Japan, which crawled across the blue sea towards China. ‘The silkworms have hardly any food and their greedy eyes are fixed on China where there is plenty. That is why they attack. To devour us.’

Popo told me of the long history of fighting between China and Japan, about how the Japanese invaded French Indochina, about things I didn’t understand then – economic sanctions and oil embargoes, Japan wanting more oil and planning to steal it from Borneo, only four hundred miles to the east, but Singapore was in the way. And she told me of a British man called Raffles, who came in 1819 and wasn’t frightened of the swamps and marshes. He had taken control of the narrow strait between Malaya and Java, and borrowed Singapore from the Sultan of Johor. She told me of how the British had come to Malacca and Penang, Labuan and, most of all, to Singapore, and how the Chinese had come too, from Fukien, Swatow and Kwantung, where she and her husband Kung-kung had been born. She told me all of this, and then she spat, ‘The filthy Japanese! They have killed many Chinese and we will always be their enemies.’

We lived in British government quarters and our house in Paterson Road was across the street from where Father worked. The house was divided into flats. We had the ground floor and a Malay police inspector lived upstairs with his family. The red-haired devil said they, too, could come into his air-raid shelter if the bombs fell. Our house was square and had wide verandas shaded with bamboo blinds. Inside we had three bedrooms, a sitting room and another room for the servants. In the garden there were hibiscus, papaya, banana, cherry and jackfruit trees, and an oriental henna with leaves shaped like little lances; the Malay women in the kampung at the back of our house came to us to ask for the henna leaves and I would watch them stain their palms and fingers for weddings and other ceremonies.

The Malay cemetery, with its lines of numbered round headstones, was next door. It was for Muslims so there were no plants or flowers. From my bedroom window I could see the Chinese cemetery on a hillock across the road, the graves terraced with marble and mosaic. Popo had told me that the richer the family, the more elaborate their ancestor’s resting-place; sometimes we played hide and seek among the graves, and when I hid, I would remember the dead all around me and not want to play any more.

A huge durian tree stood at the bottom of the Chinese cemetery; it was the tallest tree I had ever seen, fifty or sixty feet tall, perhaps more. No one dared climb it to pick the fruits, but waited for them to fall to the ground. In season, the abundance of spiny-shelled durians, hanging high in the tree, made people stare. Then the tree’s owner would hire two guards to stop anyone helping themselves to the fruit. Sometimes the guards left the tree, and when strong winds brought down the durians, the boys from the kampung ran to pick them up. We loved the sweet custardy pulp, and I asked Popo if I could search the ground beneath the tree before the guards arrived in the morning. But she told me, ‘We cannot eat fruit from that tree because it is different. The fei-shui from all those dead people feed and sustain it and we don’t eat the fei-shui of dead people.’

The Malay children upstairs wouldn’t play with us in the garden. When they came to visit, they would not eat or drink. When they cooked for us we ate their tasty food, and we couldn’t understand why they wouldn’t eat ours. Father told me about the Prophet Muhammad, and how Muslims could not eat blood or pork, or food that had been offered in prayers. Whenever Popo and my mother went to Chinatown, they would bring back meat and hang it on a bamboo pole in the garden to dry; in the heat, the fat would melt off the bacon and the pork sausages and drip to the ground. Father said the Malay children would not play in our garden because the soil had in it the fat of pigs.

Popo was always talking about the spirits of the dead and the demons who lived in the world below. If we were ill, or there was an accident in the house, she would say it was because one of us had upset the gods. She prayed hardest when she hadn’t won at mah-jongg for a long time. She would rush to the temple to find out if the gods were angry with her, and pray as hard as she could, then shower them with shong yau, oil for the lamp, and burn gold joss paper with the ends tucked in, like tiny ingots. But sometimes she thought her bad luck had been brought about by the spirits from the Chinese cemetery across the road, who came out after dusk to roam free in the upper world. ‘They are dangerous and unforgiving,’ said Popo, ‘not like the gods. The spirits are invisible, but they hear and feel us. When the gates of the world below open, they come out from the earth. Don’t pee or spit outside,’ she would warn us, ‘but if you must, remember to say first, “Forgive me.”’

After sunset, Popo would lay offerings to the spirits on the ground at the back of our house near the chicken coop, out of sight of the cemeteries. She would burn silver joss paper, lay out flowers and fruit for the Chinese spirits, and a dozen split coconuts for the Muslim spirits. My brother Beng’s job was to stoke the burning joss paper with a metal rod. He liked to pass me the hot end so that I burnt my palm, and screamed in pain. After her prayers Popo would scatter the offerings all over the garden where she said the spirits could find them, but Father worried about our Muslim neighbours. Popo ignored him, and talked of mah-jongg, so he would disappear to swim or lift weights, or to the veranda where he had hung exercise rings from the beams. Time and again he would lift himself on to those rings without removing his glasses; when he swung himself back and forth, they would fall off and smash on the floor beneath him.

One day, my father crawled under the big teak table, where I was eating my biscuits, and told me about his life before he came to Singapore. He had been born in Hainan, he told me, the second largest island in China after Taiwan. I had seen Hainan on the map Popo showed me. His parents had owned a fruit and chestnut farm, which his father worked with hired labourers to help him tend the orchards and fell the chestnut trees for timber. His mother had managed the accounts. Father told me that they found it difficult to make a living from the farm. It would rain and rain, and when the river flooded, the expensive fertilizer would be washed from the soil and they had no money to replace it. Sometimes the fruit crop was diseased and they would have to cut down more chestnut trees to sell. Father told me that chestnut wood made good charcoal, which burnt slowly and gave off an intense heat.

He also told me how, shortly after he was born and his mother was still recovering, it had rained for two weeks. The river had got higher and higher, then overflowed its banks and flooded the farm. His mother had watched the garden furniture float away, then the shed where the farm tools were kept, and the little family of piglets they had reared with the sow. When she saw that sow being swept away in the current, she had got out of bed, taken off her clothes and swum after it. But the pigs and the furniture were too far along on their journey to their new home in the sea with the fish, and she waded back to the house. There, she found she was bleeding, so the doctor came and said she would be unable to have any more children.

My grandfather only knew how to be a farmer, but my grandmother was determined that her son should not follow him and did not let him work on the farm. She wanted him to be a government official, or a school teacher. After a day’s work, no matter how tired she was, she would read the teachings of Confucius to him. She went to great trouble to buy some books in English from friends who had emigrated to Singapore, and kept them for him as a surprise birthday present. Father said that on his birthday he was in his room writing with a brush pen when he heard his mother call him from the hall. ‘Come quick! Come quick!’

When he rushed down to her she was holding out a parcel, and the excitement on her face told him it was a special gift. He took it from her, shook it, squeezed it, and finally tore off the wrapping. The books inside were not new – the covers were worn and the pages thumbed – but he didn’t mind because they were picture books with stories in English. Father told me that when he turned the pages of the first he saw pictures of fierce men, with pistols and cutlasses, dragging a boy with them; the book was Treasure Island. Another, Robinson Crusoe, had pictures of the hero, his dog and a wrecked ship. His favourite was a collection of stories that included ‘Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp’ and ‘Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves’. As he looked at the pictures, he was eager to read the stories and so, with the help of a dictionary, he began to teach himself his first foreign language.

Work never stopped on the farm, even on the wettest days. One day, when it was raining and the river was swelling, Grandfather was chopping down a chestnut tree. It fell on top of him and killed him. That day my grandmother decided she would leave the island for ever: she would emigrate to Singapore, the Lion City, with her little boy so that he would not be a farmer.

Two

Father told me how that chestnut tree had buried his father in the mud and how his mother’s tears had mixed with the rain, and that was why he had come to Singapore in 1919, when he was five. His mother was called Kum Tai, and she was only twenty-nine when the tree fell on her husband. At first Kum Tai was frightened by the hustle and bustle of the city, and as the only work she knew was farming, she bought an orchard of rambutan and mangosteen fruit trees in Nee Soon, north of Singapore, with the money from the sale of her home in Hainan.

Kum Tai named my father Poh-mun, but often called him Po-pui, which means precious seed. Father told us that when he came to Singapore he liked the different people in his new country, and their many languages, which he didn’t understand. There were brown-skinned Malay men and women in colourful sarongs, and there were Sikhs from India, who never shaved or cut their hair and wore cloth wrapped round their heads. There were Indian tea-sellers, who carried copper urns heated by charcoal fires on bamboo poles and sold ginger tea or Ceylon tea; some carried rattan baskets full of delicious roti. Father would listen to the different dialects, like nothing he had heard in his village in China, and became determined to understand them. He looked forward to visiting the town’s bookshops, and spent whole afternoons hiding among the shelves, reading and dreaming.

Kum Tai hired workers for the orchard and a servant to cook and clean. The workers spoke different dialects and she became frustrated when she could not communicate with them: when they misunderstood her instructions, they pruned the trees in the wrong way. She did more and more of the work herself, spending long hours in the plantation. At night the sweet smell of rambutan attracted swarms of bats – the locals called them flying foxes – which would tear apart the soft, hairy shells of the ripe fruit and feast on the white flesh inside. In China Kum Tai and her husband had hired fruit-watchers, who had patrolled all night and slept during the day. But in the new country my grandmother, fearful of the cost of hiring extra workers, protected the trees herself. She walked through the orchards with a lantern and a long stick to scare away the bats, and by dawn she would be exhausted. Father would find her asleep in a chair.

‘You are working too hard,’ my father said. ‘Let me do it, Mother. Let me stay up and frighten away the bats. It is only for the fruit season.’

‘Do you know why we left China after your father died?’ she said. ‘You must not be a farmer here. You must read your books and then, some day, you will be someone. It is the only way for you in this new country.’

One day, while she was supervising the plantation workers, Kum Tai fell and broke her ankle. She had to be carried back to the house. A bonesetter was called, but he did not come, and throughout the night my father heard his mother cry out in great pain. He went to her side to hold her hand.

The next morning, Lum Pang, the bonesetter, appeared at the farm. He was just five feet tall, very fat, and Father said his grin stretched from ear to ear. Everyone called him Fat Lum. He held his surgery every morning on the pavement of a busy side-street in Singapore. Fat Lum was so fat that the little stool he sat on disappeared beneath his stomach and thighs so that he seemed to be sitting on the ground. He worked next to the tooth-puller, who had a spittoon and cases of extractors and offered only one service: a toothache meant that a tooth had rotted and must come out. When the tooth-puller was called away, he would leave a set of extractors so that Fat Lum could cover for him.

When Fat Lum saw my grandmother’s ankle, he busied himself grinding roots, leaves and cacti in his granite mortar with the pestle, and softened banana leaves over his charcoal fire. Then he spread the mixture on the leaves, which he gently wrapped round my grandmother’s ankle and tied with fibres from a banana tree-trunk.

Fat Lum was a widower and, like Kum Tai, a native of Hainan Island. He had settled in Singapore many years earlier, and spoke the dialects, English and Malay. Everyone thought he was a very good bonesetter, and while Kum Tai was waiting for her ankle to mend, he came each morning with a fresh mixture of ground herbs and banana leaves. When Fat Lum applied them to her leg, he would help her with the instructions to the plantation workers, in their various dialects, then tell them what needed to be done. For the first time in the few months since she had bought the plantation, everything went smoothly for Kum Tai – especially after Fat Lum had come to work for her, alongside his bonesetting. He asked if she had space for him to live there, rather than travelling from his home in the city. He had no family ties, he said, so there was nothing to stop him. Because my grandmother was a widow, she could not allow him to sleep in the main house: that would have led to gossip and she would have lost the respect of her neighbour. Instead she put him up in one of the outbuildings used for storing fruit.

My father was pleased that Fat Lum was living with them: it would ease his mother’s workload. Fat Lum helped him, too, with the dialects. Father loved to follow Fat Lum round the orchards, listening as he gave orders to the workers. Sometimes they would speak Hylam, their mother tongue, but often Fat Lum would use another dialect – the more my father could learn, the less likely it was that he would be a farmer and end up killed by a chestnut tree, as his father had been.

Fat Lum did more and more for Kum Tai and soon he was setting hardly any bones. When he had to respond to an emergency, he would make up for lost time on the farm at the weekend, repairing the house and the outbuildings. Father would gobble his dinner each evening, then rush out to find Fat Lum so that they could sit together on the bench by the duckpond and talk. They would stay there until it was dark when the mosquitoes drove them inside.

One day Fat Lum went to the city and came back, in the middle of dinner, with a stack of books under his arm. Father’s eyes lit up. ‘Uncle Lum, are these English books for me?’ he asked. When Fat Lum nodded, Father stretched out his arms, then remembered his manners and looked at his mother: he did not know whether he should accept the gift. Kum Tai saw the joy in his eyes and knew how much he wanted the books. But she was proud: she did not want it known that she accepted gifts from her workers. On the other hand, she did not want to upset Fat Lum. She insisted on paying for the books, and said that next time all three of them would travel to the city to buy books so that Father would learn not to be a farmer. As they were in the middle of their meal, she asked Fat Lum if he would like to join them. She expected him to say no, because he was an employee, but he said, ‘Yes,’ with a smile, and lowered his huge body into a fragile rattan chair, which groaned under his weight.

Father had never seen so many English books. ‘Thank you, Uncle Lum,’ he said, as he leafed through them. ‘Can I read with you every day?’

‘Of course you can, my son,’ said Fat Lum, ‘and you must come to me if you do not understand something.’

Kum Tai noticed that Fat Lum had called him ‘my son’, and was happy that the pair got on so well together.

After that, Fat Lum and my father would sit by the duckpond each evening with the books, and if it began to rain they would shelter in the outbuilding among the crates of ripe rambutan and scarlet, green-stemmed mangosteen. Kum Tai began to worry that her son was spending too much time away from her so, instead of sending meals to the bonesetter in the outbuilding, she began to invite him to dinner so that she could keep an eye on them both. Father would bolt his food and wait for Fat Lum to finish. Then they would sit and read together under the light of the oil lamp until Kum Tai said it was time for bed. Sometimes Father would be asleep already with a book in his hand, and Fat Lum would carry him to bed. Then he would return to Kum Tai and they would chat late into the night.

Kum Tai was alone in a strange country and was grateful for the bonesetter’s attention. She thought him a good and honourable man, and feelings for him stirred in her heart. One evening, after dinner, he asked her to marry him. Father was awake in his bed in the next room and waited anxiously for her reply. He knew how difficult it had been for her, alone on the plantation, and since the arrival of the bonesetter her life had been easier. He wanted her to marry again and to sit by the duckpond with Uncle Lum.

Kum Tai and Fat Lum were married at the Chinese Consulate, then had a wedding dinner at a restaurant. The next day Fat Lum told Father that ‘Lum’ meant forest, like their plantation, and that it would be best if Father changed his name to Lum. Kum Tai agreed that they should all bear the same name, so when Father went to register at the Anglo-Chinese Primary School it was under the surname ‘Lum’.

He excelled at school. ‘Study hard,’ Kum Tai would remind him, ‘and get a government job. You must mix with city people, not farmers.’ Father told me that he spent his holidays with friends, hiking, camping and swimming in Penang, and that he always worked hard for his exams. ‘One day we will sell the plantation and move to the city,’ his mother told him. ‘But everything depends on you passing your exams and finding a good job.’

Fat Lum took over the running of the plantation and dealt with all the paperwork. Kum Tai was glad that all she had to do was sign the letters. She did not stop guarding the orchards though, and when the trees were fruiting she would walk about with her long stick and a lantern, frightening off the bats. In the mornings she was so tired that Fat Lum could get hardly any sense out of her. ‘Why not shoot those flying foxes?’ he asked. ‘Buy a gun. A few bangs here and there and they will fly away.’

Father told me that at first after Kum Tai bought her rifle things were easier. She only needed to fire a few shots and the bats would be gone for the night. Sometimes she would kill some and take them home to make bat soup. She added medicinal herbs to strengthen Father’s weak bladder so that he did not have to rush out in the middle of his lessons.