Полная версия:

Raptor: A Journey Through Birds

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thestate.co.uk

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2016

Copyright © James Macdonald Lockhart 2016

James Macdonald Lockhart asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

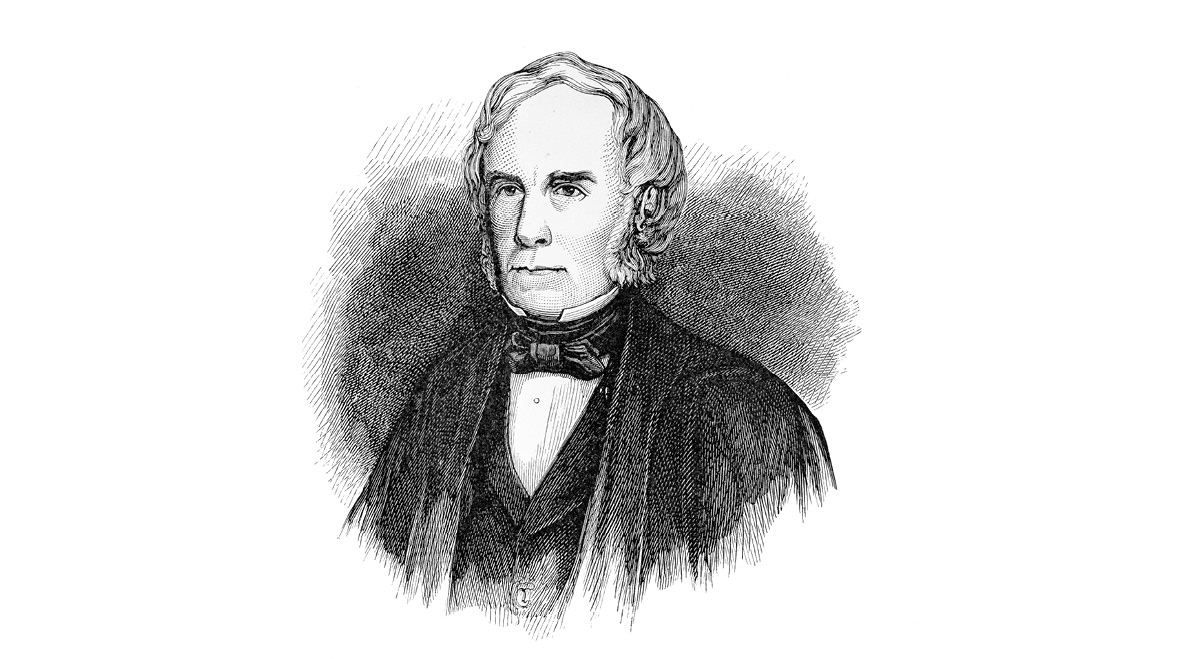

Internal illustrations taken from A History of British Birds Vol. III by William MacGillivray (William S. Orr and Co., 1852). Illustration of William MacGillivray © The Natural History Museum/Alamy Stock Photo.

Cover illustrations © Mary Evans/Natural History Museum

Cover design by Jo Walker

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007459896

Ebook Edition © February 2016 ISBN: 9780007459889

Version: 2017-01-30

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

I Hen Harrier

II Merlin

III Golden Eagle

IV Osprey

V Sea Eagle

VI Goshawk

VII Kestrel

VIII Montagu’s Harrier

IX Peregrine Falcon

X Red Kite

XI Marsh Harrier

XII Honey Buzzard

XIII Hobby

XIV Buzzard

XV Sparrowhawk

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

Epigraph

By the term Raptores may be designated an order of birds, the predatory habits of which have obtained for them a renown exceeding that of any other tribe …

WILLIAM MACGILLIVRAY,

A History of British Birds, Volume III

I

Hen Harrier

Orkney

It begins where the road ends beside a farm. Empty sacking, silage breath, the car parked amongst oily puddles. The fields are bright after rain. Inside one puddle, a white plastic feed sack, crumpled, like a drowned moon. Then feet up on the car’s rear bumper, boots loosened and threaded, backpacks tightened. Wanting to rain: a sheen of rain, like the thought of rain, has settled on the car and made it gleam. When I bend to tie my boots I notice tiny beads of water quivering like mercury on the waxed leather. Eric is with me, who knows this valley intimately, who knows where the kestrel has its nest above the burn and where the short-eared owls hide their young amongst the heather. We leave the farm and start to walk along the track towards the swell of the moor.

Closer the fields look greasy and soft. The track begins to leak away from under us and soon the bog has smothered it completely. We are amongst peat hags and pools of amber water. Marsh orchids glow mauve and pink amongst the dark reed grass. The sky is heavy with geese: greylags, with their snowshoe gait, long thick necks snorkelling the heather. You do not think they could get airborne; they run across the moor beating at the air, nothing like a bird. And with a heave they are up, calling with the rigmarole of it all, stacking themselves in columns of three or four. They fly low over the moor, circling above us as if in a holding pattern. When a column of geese breaks the horizon it looks like a dust devil has spun up from the ground to whirl slowly down the valley towards us.

Late May on a hillside in Orkney; nowhere I would rather be. It is a place running with birds. Curlews with their rippling song and long delicate bills and the young short-eared owls keeking from their hideout in the heather. And all that heft and noise of goose. When the greylags leave, shepherding their young down off the moor, following the burns to the lowland lochs and brackish lagoons, then, surely, undetectably, the moor must inflate a little, breathing out after all that weight of goose has gone.

We find a path that cuts through a bank of deep heather. It leads up onto the moor and the horizon lifts. I can see the hills of Hoy with their wind-raked slopes of scree and the sea below with its waves like the patterns of the scree. This morning the sea is a livery dark, creased with white lines that map the movement of the swell. It looks as if the sea is full of cracks, splinters of ice.

Wherever you turn on Orkney the sea is at your back, linking the islands with its junctions of light. It is not enough that the islands are already so scattered. The sea is always gnawing at them, looking for avenues to open up, fractures in the rock to prise apart. The sea up here has myriad ways to breach the land. It showers the western cliffs with its salty mists and peoples the thin soils with its kin: creeping willow, eyebright, sea thrift, sea plantain, all plants that love the sea’s breath on them.

It is a trickster sea that comes ashore with subterfuge. Orkney children once made imaginary farms with scallop shells for sheep, gaper shells for pigs, as if the sea, like a toymaker, had carved each shell and left it on the shore, waiting for a passing child. And at night selchies dock in the deep geos and patter ashore in their wet skins to slip amongst the dozing kye.

I arrived on Orkney in the dregs of a May gale. Low pressure swelling in from the Atlantic, hurting buildings and trees in their new growth, ransacking birds’ nests. Rushing across Scotland and speeding up over Orkney as if the gale had hit a patch of ice. The hardest thing of all up here, I’d heard, was learning to endure the wind, worse than the long winter darkness. It is a fidgety wind, rarely still, boisterous, folding sheds and hen houses, raking the islands’ lochs into inland seas.

This morning the wind still has a sinewy strength. Lapwings are lifted off the fields like flakes of ash. Eric is telling me about the valley. He is alert to the slightest wren-flick through the heather, seeing the birds before they arrive. When he speaks the wind gashes at his words, gets inside them. The hill is shaking with wind. We pass the kestrel’s nest and Eric points out a clump of rushes on the hillside where a hen harrier is sitting on her eggs. She is invisible on her bed of rush and ling. Her eggs are pale white, polished, stained with the colours of the nest material. If you could see like a hawk you would notice her bright yellow eyes, framed by a white eyebrow on a flat owl-like face. The face made rounder by the thick neck ruff that flickers bronze and almond-white like the ring around a planet.

Then Eric is leaving and I don’t feel I have thanked him enough. I watch him descend the moor, walking quickly along the gleaming track towards the farm and the car like a skiff bobbing amongst the lit puddles. After he has gone there is a sudden rush of rain. But the wind is so strong it seems to hold the rain up, stops it reaching the ground, flinging the shower away, crashing it into the upper slopes of the hill. Only my face and hair are briefly wet; the rest of me stays dry, as if I’d poked my head into a cloud. I have never seen rain behave this way. Months later I came across a list of beautiful old Orkney dialect words for different types of rain and wondered which described the behaviour of that wind-blown shower: driv, rug, murr, muggerafeu, hagger, dagg, rav, hellyiefer … A rug, perhaps, meaning ‘a strong pull’, rain that was being pulled, yanked away by the wind.

I had not thanked Eric nearly enough. For a walk like that will have its legacies, store itself in you like a muscle’s memory. Walking up through layers of birds, Eric explaining the narrative of the moor, where last year’s merlins hid their nest, where cattle had punctuated the dyke and damaged the delicate hillside. Till we reached a fold in the hills, the ‘nesting station’, where the hen harriers had congregated their nests, and we could go no further.

I know of other walks, like the one with Eric that morning, where their legacy is precious and defining, walks born out of that experience of guiding or being guided. My great-grandfather, Seton Gordon, in the early summer of 1906, when he was only twenty, walked into the Grampian Mountains with his boyhood hero, the naturalist Richard Kearton. That walk began with Gordon telegramming Kearton with the news he had found a ptarmigan’s nest, one of the few birds, Gordon knew, that Kearton had never photographed. Kearton packed hastily and rushed to catch the next train to Scotland. Early June, travelling north through strata of light; a 600-mile journey from Surrey to Aberdeenshire, where Gordon met Kearton off the train at Ballater. They decide to climb the mountain at night to avoid the heat of the day, setting off in the dusk, the smell of pine and birch all around them. Kearton is lame (he was left permanently lame after a childhood accident) and has to walk slowly, stopping often to rest. They toil up the mountain through the thin June dark, Kearton bent like a hunchback under the huge camera he is carrying (the heaviest Gordon has ever seen). At 1.45 a.m. a redstart’s song spurs them on.

They reach the snowfield beside the ptarmigan’s nest at 6 a.m. The sun is up and bright, the short grass sparkles. Kearton assembles his camera on its tripod and begins, cautiously, to crawl towards the sitting bird. She is a close sitter, Gordon reassures him, and if he stalks her very slowly she should sit tight. The next few moments are so precarious: Kearton exposes a number of plates and after each exposure he edges a little closer towards the ptarmigan. He stops when he is just nine feet away. He can hear his heart thumping in his chest. One last exposure, that’s it! He is close enough to see the bird breathing and the dew pearled across her back.

Seventy years later, the year before he died, Gordon was still able to recall that walk, writing about it in an article for Country Life magazine. The details of that day still fresh and resonant: the brightness of the sun that morning, the dew along the ptarmigan’s back, the cost of the telegram he sent to Kearton (sixpence).

Richard Kearton’s photographs of birds, taken at the end of the nineteenth century (many with his brother, Cherry Kearton), were to my great-grandfather what Gordon’s own photographs of birds are to me, jewels of inspiration. I grew up surrounded by Gordon’s black and white photographs of birds: golden eagles, greenshanks, gannets, dotterels … peering down at me from their teak frames. I liked to take the frames off the wall, wipe the dust from the glass, then turn the pictures over to read the captions Gordon had written on the back of each print:

– Female eagle ‘parasoling’ eaglets. The eaglet is invisible on the other side of the bird.

– The golden eagle brings a heather branch to the eyrie.

Whenever I have moved house the first pictures I hang on the new walls are two small photographs Gordon took, one of a jackdaw pair, black and pewter, the other of a hooded crow in its sleeveless silver waistcoat. Under a cupboard I keep a great cache of Gordon’s photographs in an ancient marble-patterned canvas folder. You have to untie three string bows to open the folder, and every time I do so a fragment of the canvas frays and disintegrates. My young children like to open the folder with me, and the process of going through the photographs with them – identifying the birds and mammals – has become a lovely ritual. The photographs are beautiful. I am still amazed that anyone could get so close to a wild bird as Gordon did, and photograph it in such exquisite detail. In one photograph, taken in 1922, a golden eagle lands on its nest with a grouse in its talons as a cloud of flies spumes out from an old carcass on the eyrie, as if the landing eagle has triggered an explosion. There is a stunning photograph he took of a pair of greenshanks just at the moment the birds change over incubation duties at their nest. One bird steps over the nest, ready to settle, as its mate pulls itself off the clutch of four eggs. The timing of the photograph, to capture the precise moment of the changeover, is extraordinary. The patterning on the eggs matches the patterns down the greenshank’s breast as if one has imprinted – stained – the other.

Along with Richard Kearton and another wildlife photographer, R. B. Lodge (both important influences on Gordon), Gordon was in the vanguard of early bird photography in this country. Cycling around Deeside in the first years of the twentieth century with his half-plate Thornton Pickard Ruby camera with Dallmeyer lens, Gordon took many exceptional photographs of birds and the wider fauna of the region. Upland species were his speciality: snow bunting, curlew, red-throated diver, ptarmigan … Many of these photographs he published in the books he wrote. Twenty-seven books in all, the bulk of them about the wildlife and landscapes of the Highlands and Islands. His books take up a wall of shelving in my house; greens and browns and pale silver spines, embossed with gold lettering: Birds of the Loch and Mountain; The Charm of the Hills; In Search of Northern Birds; Afoot in the Hebrides; Wanderings of a Naturalist; The Cairngorm Hills of Scotland; Amid Snowy Wastes; Highways and Byways in the West Highlands … I love their Edwardian-sounding titles, the earthy colours of their spines, the smell and feel of the books’ thick-cut paper with its ragged, crenulated edges.

Of all the birds that Gordon photographed and studied, the golden eagle was the one he came to know the best. Eagles were his abiding love, his expertise. He published two monographs on them: Days with the Golden Eagle in 1927 and The Golden Eagle: King of Birds in 1955. Both these studies, particularly the latter, went on to influence and inspire a subsequent generation of naturalists and raptor ornithologists. I often come across warm references to Gordon’s golden eagle studies in the forewords and acknowledgements of contemporary works of ornithology. His two golden eagle books were also a huge influence on me. I read them many times when I was a teenager. They set this book gestating.

And then there’s my own version of Gordon’s walk with Kearton. A family holiday on the Isle of Lewis. I am fourteen or fifteen. In the photos from that week we are sitting on the island’s vast, empty beaches, our hair washed out at right angles by the wind. Family picnics: brushing the sand off sandwiches, a lime-green thermos of tomato soup. In the background, sand dunes, a squall inside the marram grass, a blur of gannet flying west.

One day out walking on the moors I discovered something momentous. I had been following a river into the hills and as I came up over the watershed I noticed a small loch lying in a shallow dent of the moor. Wherever there is a depression in the land on Lewis, water gathers. It patterns the island intricately, beautifully. From the air much of the land looks tenuous, as if it is breaking apart, a network of walkways floating on black water. The loch I came across – a lochan – a small pool of peat-dark water, like a sunspot against the purple moor. In its centre, rowing round and round, beating the lochan’s bounds, a red-throated diver with its chick. I was mesmerised. They are beautiful, rare birds that I had read about but never seen. I sat down in a bank of heather above the loch and watched the bird’s sleek outline, the faint blush of her throat. Always the sense in her streamlined shape that, sitting on the water, she was not quite in her element, that once she dived, like an otter, the water would transform her. But I had to get back – needed to get back – and tell someone. I raced over the moor and gasped out my discovery to nodding, distracted faces.

Except for Mum. She was interested. She wanted to hear more about what I had found, got me to show her in a bird book what the diver looked like, listened when I explained how its eerie, otherworldly call was supposed to forewarn of rain. And the next morning it rained but Mum and I walked across the moor to the lochan where I had found the divers. And so I became a guide, leading my mother up the river and over the rise in the moor, and in doing so felt something Gordon must have felt guiding Richard Kearton up the flank of the mountain through the night. Me walking far too fast in my exhilaration, almost running over the peat bog, Mum calling me to slow down. Reaching the lochan: the two of us sitting down in the heather, catching our breath. Mum asking if she could borrow my binoculars.

Where Eric left me became my home for the next two days. I walked up the valley in the early morning, looking for the print my weight had made in the heather the day before; not recognisably my shape, more like a shallow quaich scooped out of the heather as if snow had slept there and in the morning left and left behind its thaw-stain on the ground. The heather held me almost buoyant in its thickness. I settled down in it like a hare crouched in its form, felt the wind running over my back.

Rummaging through Orkney’s deceased dialects I borrowed a handful of words besides those I had found to describe the different kinds of rain. Loaned words to help me navigate the land. I liked the ways, like a detailed map, they attended to the specifics, to the margins of the landscape around me. Cowe: a stalk of heather, which the wind swept like a windscreen wiper across my view of the moor; burra: hard grass found in moory soil; gayro: the sward on a hillside where the heather has been exterminated by water. And this word – a lovely gift – which described perfectly my form in the heather, beul: a place to lie down or rest.

To reach my beul on the moor I had to pass through different zones of birds. Each species seemed to occupy its own layer of the valley as if it adhered to an underlying geology of the place. Oystercatchers over a layer of marl, curlews spread across a bed of sandstone. All of these territories seeping, blurring into each other along fault lines in the moor. For a long time I struggled to get a hold of the birds. There was so much movement amongst them, so many birds to keep track of. I began to draw Venn diagrams of the birds’ locations and their movements across the moor till the pages of my notebook were filled with overlapping water rings. Gradually I came to see this small patch of moorland as the meeting point of several territories. There were four species of raptor alone breeding in the heather around me – kestrel, hen harrier, merlin and short-eared owl – and these birds’ interaction with each other, and with the large population of breeding wader birds, the curlews in particular, held me captivated over the two days I was there.

Trespassing, ghosting through all these territories like blown fragments of white silk, were the short-eared owls. The focus of their territory was a shifting area that moved around the location of the young owls as they dispersed through the deep heather. Sometimes I passed close by the owlets, hidden from me, calling loudly to their parents for food. Their high-pitched keek drilled through me as if I was passing through a scanner. Then the adult birds appeared beside me. They arrived suddenly, quietly, like shapes congealed out of mist. They flew very close, hovering just above my head. Pale white underwings marked with black crease lines as if in places the wings were beginning to thaw. Their faces a deep snow-cloud grey. Black eye-bands, like masks, which set their bright yellow eyes deep in their cupped faces. Always, as the owls hung above me, a sense of being watched and of their gaze penetrating through me. Beautiful in their buoyancy. Wing-tippers, possessed of twisting grace, flickering low over the moor like giant ghost moths.

I never expected to see so much so soon on this journey. I had set off fully expecting to be frustrated, to not find many of the birds I was looking for. But Orkney gave me so much time with its birds of prey, spoilt me utterly in that respect, so that every stage along my journey since has harked back to the time I spent on the islands.

There was an old charm used on Orkney which was supposed to heal deep cuts to the skin. To initiate the cure you had to send the name of the wounded person to the local enchanter or witch-doctor (the Old Norse term was vǫlva, meaning a wand carrier). The vǫlva would then add some new words to the patient’s name, as if they were sprinkling ingredients into a recipe. This word-concoction was then chanted repeatedly until, through some telepathic alchemy, the wound was healed. The charm worked even though the vǫlva performing it might be several miles away from their patient. After I left Orkney – and was many hundreds of miles away from the islands – I often wanted to send word back to the place, hoping the islands could perform their charm on me once more and help me find the birds I was searching for, just as they had gifted them to me while I was there.

How does a hen harrier live? It swims over the land as a storm petrel hugs the surface of the sea. It flies so low that sometimes it seems to be stirring the grass, its long legs trailing through the heather like a keel. A slow, tacking flight: float then flap. Then a twisting pirouette and it has swung onto a different tack, following another seam through the moor as if it is tracking a scent. It is like watching a disembodied spirit searching for its host, like a spirit twisting and drifting in the breeze. The harrier rides the swell of the moor, clinging to the contours for cover, creeping up on its prey and surprising it with a sudden burst of speed. The moment before it swoops, the harrier stalls, adjusts its angle a fraction – kestrel-like – then drops suddenly to the ground, talons reaching, seizing through the deep grass.

Up on the moor a cold wind has found me, poking me for signs of life. It sets me shivering in my bed in the heather. A male hen harrier is taking his time, twirling a thread over the hill. He is the colour of smoke and lavender, glaucous. He has not killed. The female is up from her nest agitating him, calling repeatedly, pushing him away from the nest site, chivvying him to go and hunt. The male slips away down the valley towards the sea. Later in the morning, when he returns, flapping heavily up towards the moor, he seems brighter, sea-gleamed, as if the sea has dressed him in its brightness.

I stay with the female harrier expecting her to quickly settle on the nest. Instead, what happens next is startling, unexpected, one of those remarkable encounters that Orkney shared with me. She began to gain height, drawing herself up to just above the horizon. Then a pause as she floated there as if in a new-found buoyancy, as if on the apex of a thermal. Perhaps the thermal had a vacuum like a lift shaft running through its centre. Whatever it was, a route through the air opened up to her like a narrow channel – a lead – opening through pack ice. For she saw it, drew her wing tips back behind her, and plunged down through the opening in a beautiful corkscrew dive. At the last moment, before she crashed into the heather, swooping up again, rising above the moor, clearing the horizon, then leaning and tipping over into another dive. She was dancing! A mesmerising sky-dance, repeated over and over again, making a pattern in the air like the peaks and troughs of a frantic graph. I paused from watching her only to wipe the condensation from the lenses of my binoculars. Then I immediately fixed back on to her display. Was she signalling to the male, or simply flexing her flight muscles after a long stint on the nest? For twenty minutes she scored the air, and held me there.