Полная версия:

A Year With Aslan: Words of Wisdom and Reflection from the Chronicles of Narnia

A YEAR WITH

ASLAN

Words of Wisdom and Reflection from

The Chronicles of Narnia

C. S. LEWIS

Edited by Julia L. Roller

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Preface

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Preface

Some books are fun to read. Rarer are those volumes that still delight us upon rereading. And then there are those rarefied species of books, those that we read, read again, and again, and keep reading. In fact, a part of us never really leaves the story. They become part of the geography of our souls, the landmarks by which we map and measure our lives. At least that has been my experience with C. S. Lewis’s Narnia books. Unlike most, I missed them completely when I was the right age to begin and only discovered them in college. And so my cycle of reading began. Especially helpful was the cover I was given by having two daughters who pleaded with me each night to read the books to them. “Well, if you insist.” Still, forever after, unbidden, and at all the right moments in my life, I saw Eustace struggle with his dragon skin, Digory debating obedience to Aslan versus saving his mother, Lucy chastising herself for sticking with the group even after she saw Aslan, Edmund facing his shame after his rescue from the White Witch, or Tirian and Jewel racing up Aslan’s mountain laughing while the dwarves think they are still in a dark hut.

We have created this volume for all those similarly haunted. Each day for a whole year brings an episode from anywhere in the seven volumes of the chronicles, an isolated story or scene that provides both delight and nourishment, an opportunity to reflect and deepen our experience of this landscape of wonder (with questions at the bottom of each selection for those who appreciate a nudge in a particular direction). I grew up in a tradition that encouraged a daily practice of reading and reflection as a spiritual workout, and we often heard admonishments for why we had to will it earnestly and overcome our natural resistance to this vital practice. (In other words, it was presented as the spiritual equivalent of “eat your vegetables.”) Yet this led me to the unexpected query, But what if I enjoyed it? Follow that line of thought and you will arrive at the very logic and purpose of this book.

We need to pause and thank Julia Roller, who selected the readings and drafted the questions; Cynthia DiTiberio, the editor at HarperOne who captained the project as well as Drinian guided the Dawn Treader; and, finally, to the C. S. Lewis Company, who graciously allowed us to play in this field. And now, for everyone else, “Farther up and farther in!”

– Michael G. Maudlin

JANUARY

JANUARY 1

The Creation of Narnia

FAR AWAY, and down near the horizon, the sky began to turn grey. A light wind, very fresh, began to stir. The sky, in that one place, grew slowly and steadily paler. You could see shapes of hills standing up dark against it. All the time the Voice went on singing. . . .

The eastern sky changed from white to pink and from pink to gold. The Voice rose and rose, till all the air was shaking with it. And just as it swelled to the mightiest and most glorious sound it had yet produced, the sun arose.

Digory had never seen such a sun. The suns above the ruins of Charn had looked older than ours: this looked younger. You could imagine that it laughed for joy as it came up. And as its beams shot across the land the travellers could see for the first time what sort of place they were in. It was a valley through which a broad, swift river wound its way, flowing eastward towards the sun. Southward there were mountains, northward there were lower hills. But it was a valley of mere earth, rock and water; there was not a tree, not a bush, not a blade of grass to be seen. The earth was of many colours; they were fresh and hot and vivid. They made you feel excited; until you saw the Singer himself, and then you forgot everything else.

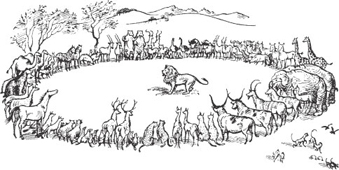

It was a Lion. Huge, shaggy, and bright, it stood facing the risen sun. Its mouth was wide open in song and it was about three hundred yards away.

– The Magician’s Nephew

What do you think it is like for Digory, Polly, and the others to stumble upon such a scene? Have you ever stumbled upon a scene of such wonder that it was hard to fathom? How did you react?

JANUARY 2

Their Own Secret Country

THE STORY BEGINS on an afternoon when Edmund and Lucy were stealing a few precious minutes alone together. And of course they were talking about Narnia, which was the name of their own private and secret country. Most of us, I suppose, have a secret country but for most of us it is only an imaginary country. Edmund and Lucy were luckier than other people in that respect. Their secret country was real. They had already visited it twice; not in a game or a dream but in reality. They had got there of course by Magic, which is the only way of getting to Narnia. And a promise, or very nearly a promise, had been made them in Narnia itself that they would some day get back. You may imagine that they talked about it a good deal, when they got the chance.

– The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

What does having a place that you dream about, whether real or imagined, do for you? Have you been able to retain that sense of imagination and dreams in your adulthood?

JANUARY 3

Into the Wardrobe

AND SHORTLY AFTER THAT they looked into a room that was quite empty except for one big wardrobe; the sort that has a looking-glass in the door. There was nothing else in the room at all except a dead blue-bottle on the window-sill.

“Nothing there!” said Peter, and they all trooped out again – all except Lucy. She stayed behind because she thought it would be worth while trying the door of the wardrobe, even though she felt almost sure that it would be locked. To her surprise it opened quite easily, and two moth-balls dropped out.

Looking into the inside, she saw several coats hanging up – mostly long fur coats. There was nothing Lucy liked so much as the smell and feel of fur. She immediately stepped into the wardrobe and got in among the coats and rubbed her face against them, leaving the door open, of course, because she knew that it is very foolish to shut oneself into any wardrobe. Soon she went further in and found that there was a second row of coats hanging up behind the first one. It was almost quite dark in there and she kept her arms stretched out in front of her so as not to bump her face into the back of the wardrobe. She took a step further in – then two or three steps – always expecting to feel woodwork against the tips of her fingers. But she could not feel it.

“This must be a simply enormous wardrobe!” thought Lucy, going still further in and pushing the soft folds of the coats aside to make room for her. Then she noticed that there was something crunching under her feet. “I wonder is that more moth-balls?” she thought, stooping down to feel it with her hand. But instead of feeling the hard, smooth wood of the floor of the wardrobe, she felt something soft and powdery and extremely cold. “This is very queer,” she said, and went on a step or two further.

Next moment she found that what was rubbing against her face and hands was no longer soft fur but something hard and rough and even prickly. “Why, it is just like branches of trees!” exclaimed Lucy. And then she saw that there was a light ahead of her; not a few inches away where the back of the wardrobe ought to have been, but a long way off. Something cold and soft was falling on her. A moment later she found that she was standing in the middle of a wood at night-time with snow under her feet and snowflakes falling through the air.

Lucy felt a little frightened, but she felt very inquisitive and excited as well. She looked back over her shoulder and there, between the dark tree-trunks, she could still see the open doorway of the wardrobe and even catch a glimpse of the empty room from which she had set out. (She had, of course, left the door open, for she knew that it is a very silly thing to shut oneself into a wardrobe.) It seemed to be still daylight there. “I can always get back if anything goes wrong,” thought Lucy. She began to walk forward, crunch-crunch over the snow and through the wood towards the other light.

– The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

What does it tell us about Lucy that she continues alone into the wardrobe even after finding something so unexpected there? Do you have this kind of curiosity? If so, how has it affected your life? If not, what would it mean for your life?

JANUARY 4

A Sense of Wonder

“THEY SAY ASLAN is on the move – perhaps has already landed.” And now a very curious thing happened. None of the children knew who Aslan was any more than you do; but the moment the Beaver had spoken these words everyone felt quite different. Perhaps it has sometimes happened to you in a dream that someone says something which you don’t understand but in the dream it feels as if it had some enormous meaning – either a terrifying one which turns the whole dream into a nightmare or else a lovely meaning too lovely to put into words, which makes the dream so beautiful that you remember it all your life and are always wishing you could get into that dream again. It was like that now. At the name of Aslan each one of the children felt something jump in its inside. Edmund felt a sensation of mysterious horror. Peter felt suddenly brave and adventurous. Susan felt as if some delicious smell or some delightful strain of music had just floated by her. And Lucy got the feeling you have when you wake up in the morning and realize that it is the beginning of the holidays or the beginning of summer.

– The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

When was the last time you felt the sense of anticipation and wonder that the four children feel upon hearing Aslan’s name?

JANUARY 5

Who Is Aslan?

“OH, YES! Tell us about Aslan!” said several voices at once; for once again that strange feeling – like the first signs of spring, like good news, had come over them.

“Who is Aslan?” asked Susan.

“Aslan?” said Mr Beaver. “Why, don’t you know? He’s the King. He’s the Lord of the whole wood, but not often here, you understand. Never in my time or my father’s time. But the word has reached us that he has come back. He is in Narnia at this moment. He’ll settle the White Queen all right. It is he, not you, that will save Mr Tumnus.”

“She won’t turn him into stone too?” said Edmund.

“Lord love you, Son of Adam, what a simple thing to say!” answered Mr Beaver with a great laugh. “Turn him into stone? If she can stand on her two feet and look him in the face it’ll be the most she can do and more than I expect of her. No, no. He’ll put all to rights as it says in an old rhyme in these parts:

Wrong will be right, when Aslan comes in sight,

At the sound of his roar, sorrows will be no more,

When he bares his teeth, winter meets its death,

And when he shakes his mane, we shall have

spring again.

– The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

What might the children be picturing from Mr Beaver’s description of Aslan? What would your reaction be if someone you knew told you there was someone in the world right now who will right all your wrongs?

JANUARY 6

The Door to Narnia

“IF ONLY THE DOOR WAS OPEN AGAIN!” said Scrubb as they went on, and Jill nodded. For at the top of the shrubbery was a high stone wall and in that wall a door by which you could get out on to open moor. This door was nearly always locked. But there had been times when people had found it open; or perhaps there had been only one time. But you may imagine how the memory of even one time kept people hoping, and trying the door; for if it should happen to be unlocked it would be a splendid way of getting outside the school grounds without being seen.

Jill and Eustace, now both very hot and very grubby from going along bent almost double under the laurels, panted up to the wall. And there was the door, shut as usual.

“It’s sure to be no good,” said Eustace with his hand on the handle; and then, “O-o-oh. By Gum!!” For the handle turned and the door opened.

A moment before, both of them had meant to get through that doorway in double quick time, if by any chance the door was not locked. But when the door actually opened, they both stood stock still. For what they saw was quite different from what they had expected.

They had expected to see the grey, heathery slope of the moor going up and up to join the dull autumn sky. Instead, a blaze of sunshine met them. It poured through the doorway as the light of a June day pours into a garage when you open the door. It made the drops of water on the grass glitter like beads and showed up the dirtiness of Jill’s tear-stained face. And the sunlight was coming from what certainly did look like a different world – what they could see of it. They saw smooth turf, smoother and brighter than Jill had ever seen before, and blue sky, and, darting to and fro, things so bright that they might have been jewels or huge butterflies.

Although she had been longing for something like this, Jill felt frightened. She looked at Scrubb’s face and saw that he was frightened too.

“Come on, Pole,” he said in a breathless voice.

“Can we get back? Is it safe?” asked Jill.

At that moment a voice shouted from behind, a mean, spiteful little voice. “Now then, Pole,” it squeaked. “Everyone knows you’re there. Down you come.” It was the voice of Edith Jackle, not one of Them herself but one of their hangers-on and tale-bearers.

“Quick!” said Scrubb. “Here. Hold hands. We mustn’t get separated.” And before she quite knew what was happening, he had grabbed her hand and pulled her through the door, out of the school grounds, out of England, out of our whole world into That Place.

– The Silver Chair

Why do you think that upon seeing something amazing she has always longed for, Jill feels frightened and hesitates? Have you ever felt like Jill, drawn towards something that seems wonderful but afraid at the same time? Would you be angry with Eustace, or relieved that he took charge of the situation?

JANUARY 7

Trust

“ARE YOU NOT THIRSTY?” said the Lion.

“I’m dying of thirst,” said Jill.

“Then drink,” said the Lion.

“May I – could I – would you mind going away while I do?” said Jill.

The Lion answered this only by a look and a very low growl. And as Jill gazed at its motionless bulk, she realized that she might as well have asked the whole mountain to move aside for her convenience.

The delicious rippling noise of the stream was driving her nearly frantic.

“Will you promise not to – do anything to me, if I do come?” said Jill.

“I make no promise,” said the Lion.

Jill was so thirsty now that, without noticing it, she had come a step nearer.

“Do you eat girls?” she said.

“I have swallowed up girls and boys, women and men, kings and emperors, cities and realms,” said the Lion. It didn’t say this as if it were boasting, nor as if it were sorry, nor as if it were angry. It just said it.

“I daren’t come and drink,” said Jill.

“Then you will die of thirst,” said the Lion.

“Oh dear!” said Jill, coming another step nearer. “I suppose I must go and look for another stream then.”

“There is no other stream,” said the Lion.

It never occurred to Jill to disbelieve the Lion – no one who had seen his stern face could do that – and her mind suddenly made itself up. It was the worst thing she had ever had to do, but she went forward to the stream, knelt down, and began scooping up water in her hand. It was the coldest, most refreshing water she had ever tasted. You didn’t need to drink much of it, for it quenched your thirst at once.

– The Silver Chair

Why won’t Aslan put Jill’s fears to rest?

JANUARY 8

Too Beautiful to Believe

“I CANNOT SET MYSELF to any work or sport today, Jewel,” said the King. “I can think of nothing but this wonderful news. Think you we shall hear more of it today?”

“They are the most wonderful tidings ever heard in our days or our fathers’ or our grandfathers’ days, Sire,” said Jewel, “if they are true.”

“How can they choose but be true?” said the King. “It is more than a week ago that the first birds came flying over us saying, Aslan is here, Aslan has come to Narnia again. And after that it was the squirrels. They had not seen him, but they said it was certain he was in the woods. Then came the Stag. He said he had seen him with his own eyes, a great way off, by moonlight, in Lantern Waste. Then came that dark Man with the beard, the merchant from Calormen. The Calormenes care nothing for Aslan as we do; but the man spoke of it as a thing beyond doubt. And there was the Badger last night; he too had seen Aslan.”

“Indeed, Sire,” answered Jewel, “I believe it all. If I seem not to, it is only that my joy is too great to let my belief settle itself. It is almost too beautiful to believe.”

“Yes,” said the King with a great sigh, almost a shiver, of delight. “It is beyond all that I ever hoped for in all my life.”

– The Last Battle

What does Jewel mean by saying that his joy is too great to let his belief settle itself? Has any news ever struck you this way? What, deep down, have you hoped for all your life?

JANUARY 9

The Call

ASLAN THREW UP HIS SHAGGY HEAD, opened his mouth, and uttered a long, single note; not very loud, but full of power. Polly’s heart jumped in her body when she heard it. She felt sure that it was a call, and that anyone who heard that call would want to obey it and (what’s more) would be able to obey it, however many worlds and ages lay between. And so, though she was filled with wonder, she was not really astonished or shocked when all of a sudden a young woman, with a kind, honest face stepped out of nowhere and stood beside her. Polly knew at once that it was the Cabby’s wife, fetched out of our world not by any tiresome magic rings, but quickly, simply and sweetly as a bird flies to its nest. The young woman had apparently been in the middle of a washing day, for she wore an apron, her sleeves were rolled up to the elbows and there were soapsuds on her hands. If she had had time to put on her good clothes (her best hat had imitation cherries on it) she would have looked dreadful; as it was, she looked rather nice.

Of course she thought she was dreaming. That was why she didn’t rush across to her husband and ask him what on earth had happened to them both. But when she looked at the Lion she didn’t feel quite so sure it was a dream, yet for some reason she did not appear to be very frightened. Then she dropped a little half curtsey, as some country girls still knew how to do in those days. After that, she went and put her hand in the Cabby’s and stood there looking round her a little shyly.

– The Magician’s Nephew

Why do you think Aslan chose a Cabby and his wife as the first king and queen of Narnia? She doesn’t know what she’s been called to do, yet she seems to trust that all is as it should be. Though this situation is extreme, have you ever found yourself in an unexpected place but where, deep down, you knew you were supposed to be?

JANUARY 10

Picking Sides

THEY WERE ALL STILL WONDERING what to do next, when Lucy said, “Look! There’s a robin, with such a red breast. It’s the first bird I’ve seen here. I say! – I wonder can birds talk in Narnia? It almost looks as if it wanted to say something to us.” Then she turned to the Robin and said, “Please, can you tell us where Tumnus the Faun has been taken to?” As she said this she took a step towards the bird. It at once flew away but only as far as to the next tree. There it perched and looked at them very hard as if it understood all they had been saying. Almost without noticing that they had done so, the four children went a step or two nearer to it. At this the Robin flew away again to the next tree and once more looked at them very hard. . . .

“Do you know,” said Lucy, “I really believe he means us to follow him.”

“I’ve an idea he does,” said Susan. “What do you think, Peter?”

“Well, we might as well try it,” answered Peter. . . . They had been travelling in this way for about half an hour . . . when Edmund said to Peter, “if you’re not still too high and mighty to talk to me, I’ve something to say which you’d better listen to. . . . [H]ave you realized what we’re doing? . . . We’re following a guide we know nothing about. How do we know which side that bird is on? Why shouldn’t it be leading us into a trap?”

“That’s a nasty idea. Still – a robin, you know. They’re good birds in all the stories I’ve ever read. I’m sure a robin wouldn’t be on the wrong side.”

“If it comes to that, which is the right side? How do we know that the Fauns are in the right and the Queen (yes, I know we’ve been told she’s a witch) is in the wrong? We don’t really know anything about either.”

“The Faun saved Lucy.”

“He said he did. But how do we know?”

– The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

If you were Peter, how would you determine which is the right side? When have you been unsure whether someone was trustworthy or not? How did you decide?

JANUARY 11

The Source of Wisdom

AFTER THIS, Caspian and his tutor had many more secret conversations on the top of the Great Tower, and at each conversation Caspian learned more about Old Narnia, so that thinking and dreaming about the old days, and longing that they might come back, filled nearly all his spare hours. But of course he had not many hours to spare, for now his education was beginning in earnest. He learned sword-fighting and riding, swimming and diving, how to shoot with the bow and play on the recorder and the theorbo, how to hunt the stag and cut him up when he was dead, besides Cosmography, Rhetoric, Heraldry, Versification, and of course History, with a little Law, Physic, Alchemy, and Astronomy. Of Magic he learned only the theory, for Doctor Cornelius said the practical part was not proper study for princes. “And I myself,” he added, “am only a very imperfect magician and can do only the smallest experiments.” Of Navigation (“Which is a noble and heroical art,” said the Doctor) he was taught nothing, because King Miraz disapproved of ships and the sea.