Полная версия:

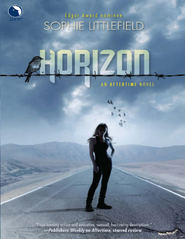

Horizon

Of living things there were none

But they carried on

Cass Dollar has survived the worst Aftertime has to offer: civilization’s meltdown, humans turned mindless cannibals, men visiting and revisiting evil upon one another.

If Cass can overcome the worst of what’s inside her—after all, she was once a Beater herself, until she mysteriously healed—then their journey may finally end. And a new horizon will be born.

Praise for Sophie Littlefield

“Littlefield turns what could be just another zombie apocalypse into a thoughtful and entertaining exploration of many themes.… Littlefield has a gift for pacing, her adroit and detailed world-building going down easy amid page-turning action and evocative, sensual, harrowing descriptions that bring every paragraph of this thriller to life.”

—Publishers Weekly on Aftertime (starred review)

“Driven by a tough, smart heroine with a dark past… Littlefield’s compelling writing will keep readers turning pages late into the night to find out what happens next. Outstanding!”

—RT Book Reviews, on Aftertime (Top Pick, Seal of Excellence)

“Sophie Littlefield shows considerable skills for delving into the depths of her characters and complex plotting as she disarms the reader.”

—South Florida Sun-Sentinel

“I’m geeking out of my mind after reading Aftertime because I felt almost the same way reading it as I do watching The Walking Dead: captivated.”

—All Things Urban Fantasy

“A new generation of post-apocalyptic fiction: a unique journey into a horrifying world of zombies, zealots and avarice that examines the strength of one woman, the joy of acceptance and the power of love. A must read.”

—JT Ellison, author of A Deeper Darkness

”Grab a Littlefield pronto.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Littlefield excels at keeping the momentum going and she knows how to inject a huge beating heart into any story, even one in which humanity is barely alive.”

—Pop Culture Nerd

“Rebirth not only matches Aftertime’s thematic punch, it just may have surpassed it!.…Littlefield’s Aftertime trilogy is top-notch post-apocalyptic fiction. It’s an innovative take on the zombie mythos. It’s a heartrending love story….If Aftertime was [Stephen] King’s The Stand in a bra and panties then Rebirth is McCarthy’s The Road in a dress and sensible heels.”

—Paul Goat Allen, BarnesandNoble.com

“A book about what it means to love and be human disguised as a story about a zombie-riddled dystopia.”

—RT Book Reviews on Rebirth

“From H.G. Wells to Max Brooks to Cormac McCarthy, the End Times have always belonged to the boys. Sophie Littlefield gives an explosive voice to the other half of the planet’s population…a whole new kind of fierce.”

—Laura Benedict, author of Isabella Moon

“You will have a very good day, indeed, when you enter the wonderful world of Sophie Littlefield’s fiction.”

—Mystery Lovers Bookshop

Horizon

Sophie Littlefield

In honor of all beginnings

failed and fresh

hopeless and hopeful

And for M:

safe in His arms

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1

ALL THOSE SHADES of red—candy-apple and cinnamon and carnelian and rust and vermilion and dozens more—people arriving for the party stopped and stared at the paper hearts twirling lazily overhead on their strings. No one had seen anything like it since Before. No one expected to see anything like it again Aftertime.

Except, maybe, for Cass, who dreamed lush banks of scarlet gaillardia, Mister Lincoln roses heavy on glossy-leafed branches, delicate swaying spires of firecracker penstemon. Cass Dollar hoarded hope with characteristic parsimony when she was awake, but since coming to New Eden her dreams were audacious, greedy, lusting for color and scent and life.

Even here, in this stretch of what had once been Central California valley farmland—rarely touched by frost, the sun warming one’s face in March and burning in April—even here it was possible to long for spring in February. In her winter garden, homely rows of black-twig seedlings and lumpy rhizomes protruded from the dirt. There was little that was lovely save the pale green throats of kaysev sprouts dotting the fields beyond, skimming the entire southern end of the island with verdant life beyond the few dormant acres in which Cass toiled. At the end of each day she had dirt under her nails, pebbles in her shoes, the sweet-rot smell of compost clinging to her skin and nothing to show for it yet in the fields.

Cass was not the only one who was tired of winter. In fact, the social committee’s first idea had been a cabin-fever dance, until someone suggested the more upbeat Valentine’s Day theme. There was romance to be found in New Eden, for some—different than Before, of course. Some kinds of human attraction thrived in an atmosphere of strife and danger. Others waned. Cass couldn’t be bothered to care.

It wasn’t the first time she’d ignored the social committee’s call for volunteers, though it wasn’t like she was swamped with work. The pruning was done. She’d sprayed the citrus with dormant oil she’d hand-pressed from kaysev beans, and she covered the thorny branches whenever nighttime temperatures dipped. A second round of lettuces and cabbages and parsnips were planted. Beyond weeding and the eternal blueleaf patrol, there would be little else to do until warmer weather launched the growing season into full swing. So Cass would have had plenty of time to join the other women in turning the public building into a party room, fashioning decorations from bits gathered from all around the islands. She’d declined to help as they set aside ingredients for special dishes and tested out cocktails made with kaysev alcohol, its gingery taste overpowering anything else they tried to mix it with. The committee had even talked the raiding parties into bringing home scrap wood for the past two weeks, enough for a bonfire to burn until the wee hours.

Cass watched them as she walked home across the narrow bamboo bridge from Garden Island, stretching her tired limbs and working the kinks out of her neck, sore from the backbreaking work of checking the kaysev for blueleaf every afternoon. The sun was still high enough to offer some warmth, so they’d thrown open the skylights and French doors to let it in on their party. Once, the building had been the weekend getaway of some tech baron with lowbrow taste, a man who preferred booze cruises and wakeboarding to wine tasting in Napa. Most of the residents of the banks along the farm channels opted for trailers and prefab buildings and listing shacks, so the house stood out for both its size and the quality of its construction. Well before Cass had arrived in New Eden, all the non-load-bearing walls had been removed, opening it up; there were foosball and pool tables, bar stools, leather furniture, a community center of sorts. A clubhouse surrounded by the little town that had sprung up on three contiguous islands wedged in the center of a waterway that had been nameless and unremarkable Before.

It was supposed to be called Pison River now, after one of the four lost rivers that carried water away from Eden in the Bible. But the Methodist minister who had named the river had died in a cirrhotic coma after coughing up black clotted blood. He had the disease long before coming to New Eden, but everyone had taken to calling it the Poison River instead.

Cass slipped just inside, curious about the party preparations despite herself. There was Collette Portescue, with her signature apron and a colorful scarf in her hair. Collette was inexhaustibly cheery, a born organizer, a Sacramento socialite who’d found her true calling only after she lost everything.

“Cass! Cass, there you are.” The woman’s cultivated voice called to her now, unmistakable in the high registers over the murmurs of the other volunteers and a handful of early guests. Even though she’d agreed to this, Cass’s gut tightened as Collette put a drink cup down and rushed toward her on—Cass’s eyes widened with astonishment—teetering red satin high heels. Beneath the wrinkled linen of her embroidered apron, Collette wore a tight red jersey dress. Cass glanced around at the others; some of them had made an effort, with hair washed and tied back, even an occasional slash of lipstick or jingling silver bracelet—but February was still February and most people wore layers to stay warm, none of it new and none of it truly clean. It was a testament to Collette’s fierce commitment to New Eden’s social life that she stood before Cass with her arms bare and her hair in home-job pin curls.

Her smile was as splendid as ever—that kind of dental work probably came with an apocalypse-proof guarantee—and her kindness was genuine, only kindness felt like a blade to Cass’s heart and forced her to turn away, pretending to cough.

“Oh, precious, you haven’t got that bug that’s going around, have you?” There was a faint note of the South in Collette’s voice, a hint of the Miss Georgia crown she’d worn four decades ago. The early eighties would have been the perfect era for her—big hair, big parties, big spending. Austerity never seemed like a greater affront than it did where Collette was concerned.

“No, ma’am, just—dust, maybe.”

Collette nodded. “Tildy and Karen have been up on ladders all afternoon, probably knocked some loose. I should have had them take rags up there with them! But, honey, come with me now, let me show you what I need....”

Collette dragged her through the milling little crowd of Edenites who held drinks in plastic cups and chatted over the sounds of Luddy Barkava and his friends warming up in the corner. On long tables at the back wall of the public building, where the wealthy entrepreneur had once installed a pair of four-thousand-dollar dishwashers, were the makings of the centerpieces, such as they were: four mismatched vases and bowls and piles of plants that Cass had cut from the winter-blooming garden near the island’s shore. There were coral fronds of grevillea, creamy pink-tinged helleborus already dropping petals, tight clusters of tiny skimmia berries. Cass sighed. These were the only flowering plants she’d been able to grow this winter. The helleborus seed had been raided from a garden shed; the others plants were returners, species that had disappeared during the biological attacks and the Siege, and only now were starting to show up again.

These plants were never meant for floral arrangements; they were merely the hardiest, the sturdiest, the first to come back Aftertime, fodder for birds and insects, early drafts in the earth’s bid for return. They were not especially lovely, and it would take skill to make them appear so.

And Cass was no florist.

She touched a cluster of glossy oval skimmia leaves. “I don’t know—”

“Trust me, anything you do will be an improvement. June found you some stuff. Ribbon and…I don’t know, it’s all right there. Gotta run. You’ll do a marvelous job!”

Collette was off to organize the volunteer bartenders, to untangle paper hearts whose strings had gotten twisted, to admonish Luddy and his little band to play only cheerful songs. Luddy had been in a thrashcore band of local renown on the San Francisco scene; now he spent his days building elaborate skateboard ramps along the island’s only paved stretch of road. It was a testament to Collette’s charisma that in her wake the band started in on a jittery minor-key version of “Wonderful Tonight.”

And Cass got to her task, as well, starting with the berry stalks in the center of the vases and bowls and filling in with the more delicate flowers and leaves. She was winding lengths of wired organza ribbon through the stems—where June found such a luxury, Cass had no idea, but you never knew what the raiders would bring back from the mainland—when she sensed him behind her and she closed her eyes and let it come, the fading of the other sounds in the room, the heating of the air between them.

“Collette put you to work, too, huh?” His voice, low and gravelly, traced its familiar liquid path along her nerves. He was standing too close. But Dor was always too close. Cass pushed a hand through her hair, grown in the past few months well past her shoulders and released, for the occasion, from her usual ponytail, before turning to face him.

His expression was faintly mocking. In the sunset glow diffusing through the tall windows of the public building, his face was tawny and sun-browned from his work outside, just like her own. The scar that bisected one eyebrow had faded considerably since she first met Dor six months earlier, but a new one puckered a crease along his skull that disappeared into his silver-flecked black hair. Cass had been there when the bullet barely missed killing him. Here in New Eden, under the ministrations of Zihna and Sun-hi, it had taken him only a few days to recover enough to insist on leaving his sickbed.

Of course, he had other reasons to want to leave the little hospital, reasons neither of them forgot for even a day.

Watching her watching him, Dor leaned even closer, inclining his head so that his too-long hair fell across the top scar, obscuring it. Cass doubted he was even aware of this habit, which had nothing to do with vanity. Like so many men Aftertime, Dor didn’t like to talk about himself, about who he had been and where he came from. Though insisting its way to the surface, the scar was in the past.

She was in the past, as well, for that matter.

Except neither of them could quite seem to remember that.

“Where’s Valerie?” Cass asked, ignoring his question. She would have expected the woman to be here already, with her embroidery scissors and pins in her mouth, doing last-minute repairs for all the women who’d managed to pull together something special for the party. Most days, she did mending and alterations in her small apartment—just two rooms, the back half of a flat-bottom pleasure boat grounded and rebuilt by the two gay men who shared the front—but for the parties given by the social committee, she came early and sewed on loose buttons and took in seams and tacked up hems. Valerie loved to help, to feel needed. She had a pretty spilled-glass voice and a ready smile.

She was a very nice woman.

Dor grimaced. “She’s not feeling well.”

Again. Cass nodded carefully. Valerie’s stomach pains came and went, the sort of thing one managed Before with medication and special diets, but that one just endured nowadays.

Truly, it would have been so much easier, so much less complicated if she was here right now, in one of her old-fashioned A-line skirts and Pendleton jacket, a velvet headband smoothing back her glossy dark hair. Sammi said Valerie looked like a geek, and Cass supposed it was true, but she was pretty in a fragile way and if she were here she would be with Dor and there would be no danger from the thing that loomed between them.

“I’m sorry,” Cass muttered, meaning it. “What have you been doing all day?”

Dor shrugged in the general direction of the back of the building. “There’s some rotted siding along the back—Earl and Steve brought back some lumber and we’ve been replacing it. Trying to get finished before it rains.”

“Lumber?”

“Figure of speech—they took down an old house along Vaux Road. We’ve been cannibalizing it for parts.”

“You smell like you’ve worked two days straight.”

“I was going to take a shower…before this thing starts.”

“I think it’s already starting.” Luddy’s band, rehearsing their party sets, had segued into “Lola” and the conversation swelled as people finished their first round and went back for refills. Cass wouldn’t be joining them.

“You gonna be here later?”

Cass shrugged, staring into Dor’s eyes. They were a shade of navy blue that could easily be mistaken for brown. When he was angry they turned nearly black. Very occasionally, they were luminous colors of the sea. “I don’t know…I’m tired. Ingrid’s had Ruthie all day. I need to go check on her. I might just turn in early.”

Dor nodded. “Probably best.”

“Yeah. Probably.”

A group of laughing citizens rolled a table covered with pies into the center of the room and a good-natured shout went up from the crowd. Everyone knew they’d been hunting all day yesterday for jackrabbits and voles for meat pies. So the three hawthorn-berry pies were a surprise. Cass knew all about them, though, for she had been the one tending the shrubs hidden on the far end of Garden Island down a path that only she and her blueleaf scouts ever used, or sometimes the kids when they wanted to watch the Beaters.

After an autumn harvest the shrubs had surprised her by reblooming. She could not say why or how that had happened, other than the fact that kaysev did odd things to the earth. When it first appeared, people worried that kaysev would strip the soil of its nutrients in a single growing cycle. The opposite seemed true. There were other cover crops—rye, for one, planted to give overworked soil a break and renew minerals—but Cass had never seen one behave like kaysev.

The hawthorn bushes’ second bloom was scant, and after Cass picked enough for the pies, the small berries were nearly all gone. The few that remained weren’t enough even for pancakes. Cass would give them to Ruthie and Twyla when they were ripe, and they would get the sweet juice all over their faces. A treat, something to enjoy as they waited out the winter.

Winter was tough on children, the cold days and early nightfalls. They had no television. No electronic games. No radios. Not even lamps, except for special occasions. Children got bored and then they got restless.

Cass could sympathize. She got restless, too.

Chapter 2

AN HOUR AFTER sundown Cass was back in the room she shared with Ruthie, one of three cobbled-together boxes that formed a sloping second-floor addition to an old board-sided house. These were not coveted rooms, but Cass was among the most recent to arrive at New Eden and so she took what was offered without complaint.

Besides, even with that she didn’t mind. What the builders of the ramshackle house lacked in skill, they made up for in imagination. The rooms lined a narrow hall that overlooked a spacious living room, the body of the original house, whose roof had been sheared off to accommodate the second floor. There were two tiny rooms at either end of the hall, and Ruthie and Twyla loved to use them for imaginary boats or stores or churches or zoos or schools, and since no one really owned anything, they were free to borrow props from all over the house. Buckets became steering wheels, folded clothes became racks of fancy dresses, dolls became dolphins bobbing on imaginary seas.

Twyla, who was older than Ruthie—nearly five—remembered some of these things from Before. But to Ruthie they were entirely make-believe.

Ruthie was telling Cass about a book that Ingrid had read them that evening. Fridays were Ingrid’s turn to watch the four youngest children—the girls plus her two sons, age one and three—and she stuck to the most educational books from New Eden’s lending library, biographies and how-things-work and math books. She also made flash cards with pictures of things long gone, like birthday cakes and puppies and helium balloons and ice skates. Cass and Suzanne secretly called Ingrid “Sarge”—at least, they had before Suzanne mostly quit speaking to her—but Cass felt a hollow pang whenever she saw Ingrid bent earnestly over the little ones, pouring herself into lessons they were too young to understand.

Cass had once felt that passion. When Ruthie had been missing, Cass’s hunger for her daughter was stronger than her own pulse, a primal longing. Now she’d had Ruthie back for half a year, but sometimes Cass felt like she was losing the thread that bound the two of them together.

So she listened and she listened harder.

“The fork goes on this side,” Ruthie said in a voice that was little more than a whisper, patting the mattress on the floor. She was a quiet child; she never yelled, never shouted with joy or rage. “The knife and spoon go here. You can put the plate in the middle. That’s where it goes.”

Cass murmured encouragingly, folding back the sheets and blankets as she listened. These lessons were pointless, but what else could she do? For some, the old rituals brought a kind of solace. Ingrid was such a person.

The room was illuminated by a stub of candle melted to a plate, and when Ruthie was tucked in she blew the candle out, as was customary. Candlelight was to be conserved, to be used only when necessary.

“Can I help set the table tomorrow?” Ruthie asked, yawning. Tomorrow Suzanne would watch the kids so the other two could work, the three of them rotating every three days. Despite their troubles, Suzanne and Cass had an unspoken agreement never to let their discord affect the children.

Cass calculated what needed doing tomorrow—Earl had promised to come to Garden Island in the afternoon and look at some erosion that was threatening the area Cass had tilled for lettuce along the southern bank—but she could knock off after that, come by and get Ruthie. They could help with dinner, eat early and still have time to visit the hospital.

It had been a long time—too long—three weeks, a month? She hadn’t meant to let it happen, but it had gotten harder and harder to go there.

But yes, she had promised herself she would be better.

They could get there in time to help Sun-hi with the last few chores of the day. And Ruthie actually enjoyed the visits—she was too little to be afraid.

“Yes, Babygirl,” Cass said, trying to keep her tone light. “And then you can wash all the dishes. And dry them and put them away. How does that sound?”

“Will you help me?” Ruthie asked doubtfully, sleep overtaking her voice. So serious, Ruthie never seemed to know when Cass was teasing her.

“Of course I’ll help you,” Cass whispered, laying her head down on the mattress next to Ruthie’s, her knees on the carpet. She felt Ruthie’s breath on her cheek. Before long it became regular with sleep.

Cass kissed her softly and crawled over to the corner of the room where she kept their few special things in a cabinet that had once held electronics, part of a “media center” in a time when media still roamed the earth and electric byways. She ran her hand over the books, the toys and jars of lotion, the wooden flute and the little glass bowl of earrings, and only then did she take down the antique wooden box that had held a board game a hundred years ago. She’d traded a potted lime-tree seedling for the box, which a woman had carried with her all the way from Petaluma in her backpack. On its surface, in flaking paint, was the image of a dancing bear balancing an umbrella on its snout. No one knew what the box meant to the woman, or why she’d carried it all those miles, because not long after arriving in New Eden, she cut her foot on a piece of broken bottle in the muddy shores, and died three weeks later when the infection reached her heart.