Полная версия:

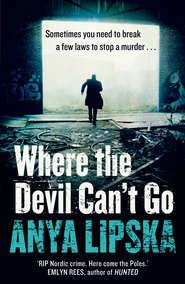

Where the Devil Can’t Go

WHERE THE

DEVIL CAN’T GO

ANYA LIPSKA

Copyright

The Friday Project

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by The Friday Project in 2013

Copyright © Anya Lipska 2013

Anya Lipska asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007504589

Ebook Edition © February 2013 ISBN: 9780007504596

Version: 2015-02-18

For Tomasz

Our homeland is on the verge of collapse … The atmosphere of conflicts, misunderstanding, hatred causes moral degradation, surpasses the limits of toleration. Strikes , the readiness to strike, actions of protest have become a norm of life.

Citizens! … I declare, that today the Military Council of National Salvation has been formed. In accordance with the Constitution, the State Council has imposed martial law all over the country.

General Jaruzelski, Communist Leader of Poland, speaking on December 13, 1981

The winter is yours, but the summer will be ours.

Solidarnosc graffiti during martial law,

Poland, 1981–83

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Praise

About the Publisher

Prologue

If I can just crawl to the bottom step, I might be able to reach the stair rail, pull myself up with my good arm. My legs are useless – the fall must have broken something in my back.

I knew the risk. I knew when I told the boy who I was that he might kill me, but I had to do it – how else could I bring up the matter of our mutual friend? At first, he didn’t believe me, didn’t remember my face. I had to raise my voice then, remind him what had happened to him – incredible that he should need reminding!

That did the trick. Something in his eyes changed.

I told him I regretted his sacrifice, tried to explain what a dangerous time it had been for the country – if we had lost our nerve, well, there would have been tanks on the streets again – and not our own ones this time.

He didn’t see it that way. So I ended up in a puddle of my own piss on the cellar floor.

It was worth it. The boy read the document. He wants revenge – I saw it in his eyes – and that means I’ll get mine.

If I can just make it to the bottom step.

One

Janusz slammed the younger man so hard against the flat’s freshly painted plasterboard that he heard the fixings pop, and twisted the neck of the guy’s sweatshirt around his throat.

‘Honest to God, Janusz!’ Another shove. ‘Sorry. Panie Kiszka. The contractor didn’t pay me yet, but in two days I’m getting a thousand, I swear on the wounds of Christ.’

As Janusz paused for breath, his free hand propped against the wall, he caught his reflection in the triple-glazed window next to Slawek’s shoulder. It showed a big man in early middle age, wide-shouldered and lean, and with a strong jaw, yes – but with the unmistakable beginnings of a stoop, and a scatter of grey in the thick dark hair. Naprawde, he was getting too old for this kind of thing.

Straightening his spine with caution, but keeping a grip on Slawek’s collar, he scanned the room, a newly fitted ‘luxury’ studio apartment in a tower block overlooking the moonscape of the Olympic construction site. Floor to ceiling windows framed the black skeleton of the half-built main stadium, which sat like a giant teacup, ringed by attending cranes, seventeen floors below. When the block was finished, the view would put an extra forty, maybe fifty thousand, on the fat price tag.

Unbelievable. From what he’d seen of Stratford – and he saw far too much of it for his liking, now so many Poles were working around the Olympic site – the place was a dump. After the Luftwaffe had flattened it, along with most of the East End, the town planners had decided to recreate the town centre as a poured concrete shopping mall on a giant three-lane roundabout. It reminded him of the stuff the Communists had crapped out all over Poland in the fifties and sixties.

Slawek was two weeks late with payment and as full of bullshit as ever. The power hammer Janusz had supplied over a month ago, still labelled ‘Property of the Department of Transport’ stood propped against the cream-coloured bulk of an American-style Smeg. Janusz knew that the fancy fridge – along with the rest of the gleaming kitchen appliances – was missing the manufacturer’s serial number, because he had removed it himself with an angle grinder before delivery.

‘The quicker I finish this job, the quicker I get paid – and you get paid,’ said the young man, taking advantage of the pause in hostilities.

Janusz had spent enough of his youth on building sites to see past the superficial gloss to the flat’s shoddy finish. He’d have got a bollocking for the slapdash plastering, and for using non-galvanised screws in the cooker hood, which would rust solid at the first blast of kitchen steam. All the same, it did look almost finished. He sighed. As much as he needed the cash, he had to admit Slawek had a point.

He thumped him once more, half-heartedly, against the wall. ‘Slawek, you are a pointless fucking hand-job.’ But Slawek caught the change of tone, and sure enough, the big man suddenly dropped him with a gesture of disgust.

‘One more week – and you screw me around next time, they’ll have to pull that jackhammer out of your arse.’

‘Tak, tak. I really appreciate it, panie Kiszka.’ Slawek practically skipped as he followed Janusz to the door. ‘Maybe I can do some small job for you, to say thanks?’

That brought an explosion of laughter from Janusz. ‘I wouldn’t let you build me a cat flap!’ he said over his shoulder. Slawek’s renovation of a three-storey Georgian townhouse in Notting Hill was infamous in the Polish community: he’d knocked down a supporting wall and created W11’s first Georgian bungalow. The local council – not to mention the client, an unhappy Russian billionaire – was still looking for him. Slawek’s face crumpled in protest.

‘One mistake doesn’t make me a bad builder,’ he shouted down the corridor after Janusz as the lift doors closed behind him.

Three floors down, a laughing group of young men piled in, carrying tools and paint kettles. Janusz saw that they all wore number one crew cuts – the ultra-short cut that had once been the badge of a recently completed stint in the military. Many young Poles apparently still favoured it, even though compulsory national service had been abandoned a year or more back.

On seeing the older man, they quieted and bobbed their heads: ‘Dzien dobry, panu,’ using the respectful form of address. Good lads, thought Janusz. But within seconds, their chatter, the closeness of their bodies, and the press of the lift wall at his back started to stir the old feeling of dread in the pit of his stomach. His breathing grew shallow and the vaporous tang of solvent seemed to suck the air from his lungs.

As the lift plunged, the tallest one met his eye, grinned, and with an unpleasant jolt, Janusz saw his younger self reflected back at him, the unfinished features and gangly limbs, the absurd optimism. Then, without warning, another image, pin-sharp and even less welcome: Iza’s face, freckled, laughing as she clattered down the stairs of the university. He squeezed his eyes shut, willing away the other memories.

The helmeted ranks of ZOMO advancing through blizzarding snow, the obscene thump thump of lead-filled truncheons striking human flesh.

His breathing ragged now, Janusz hit the button for the next floor and pushed past the startled boys to the door, muttering some excuse. He took the remaining five flights down to the lobby at a run. Out in the street, he sucked in life-saving lungfuls of the chilly spring air.

Kurwa mac! Was he constantly to be reminded of the past by this deluge of young Poles?

‘Bloody foreigners,’ he said out loud, startling an old lady waiting at the bus stop. Suppressing a grin, he murmured an apology and headed to the café across the street.

Janusz inhaled the savoury aromas emanating from the café’s kitchen as he studied the menu, chalked up on a blackboard.

‘Dla pana?’ asked the fair-haired, plump-cheeked girl behind the counter, pen and pad poised.

‘Your bigos. Is it homemade or out of a tin?’ he asked. She made as if to cuff the side of his head. He ducked, grinning, and took his glass of lemon tea – the real thing, not some powdered rubbish – to the only empty table, beside a window made opaque by the café’s steamy fug.

The Polska Kuchnia, or Polish Kitchen, was a good half mile from the commotion of the Olympic site, but the place was packed with groups of construction workers in cement-stained work clothes filling up on the solid, comforting food of home: pierogi, golabki, flaki. These were the men turning the architects’ blueprints into reality: the stadium, the velodrome, the athletes’ village, as well as the high-rise apartment blocks shooting up around the edge of the five-hundred-acre site.

The young couple who ran the place had tried to make it more homely than the standard East End greasy spoon: there were checked tablecloths, brightly coloured bread baskets, even a crocus in a jam jar at every table. If it weren’t for the growl of passing lorries, thought Janusz, you could almost pretend you were in a little restaurant somewhere in the Tatra Mountains.

Just as the girl set down his hunter’s stew – and it looked like a good one, with slivers of duck, as well as the usual pork and kielbasa, poking through the sauerkraut – the street door crashed open and Oskar arrived.

Short, balding and barrel-chested, Oskar scoured the café with a belligerent stare, and found his target – a group of young guys in a corner laughing and joking over the remains of their meal. Planting his legs apart, he let fly with a volley of Polish.

‘What in the name of the Virgin are you still doing here, you sisterfuckers?’ he boomed. ‘What did I tell you yesterday? If you are late back again I’ll have the contractor on the blower cutting my balls off.’

The lads scrambled to their feet, a couple of them falling over their chair legs in their haste to get to the door, amid a barrage of laughter from the café’s other occupants, who’d stopped eating to enjoy the show. But Oskar was merciless.

‘Don’t try to hide your ugly mush from me, Karol, you cocksucker. Maybe your mummy did name you after the fucking Pope, God rest his soul,’ he made the sign of the cross without pausing for breath, ‘but I still haven’t forgotten that granite worktop you wrote off and I’m gonna fuck you up the dupa on payday.’

As the last of them scurried out, heads down, Oskar subsided, satisfied. Then, seeing Janusz, his face split in a grin. ‘Czesc, Janek!’

Janusz stood to greet his friend and, without thinking, put out his hand. Oskar roared with laughter and, ignoring it, embraced his mate in a full bear hug, kissing him on alternate cheeks three times. Janusz cleared his throat: between Poles the effusive greeting was no big deal, but after two decades in England, it made him squirm.

Oskar put a hand on one hip and mimicked an effete handshake as he sat down. ‘You’ve been in England too long, mate. Soon you’ll be wanting to fuck with men!’ He chuckled delightedly at his joke.

Janusz smiled wearily. He loved Oskar like a wayward kid brother – a friendship that dated back to their first day of military service in 1980 – but he could be a pain in the ass. He could picture it still. A rainy day behind the barbed wire of Camp 117 in the Kashubian Lakeland, and the line of new conscripts, heads newly shorn and uniforms at least two sizes too big, looking more like bedraggled baby birds than soldiers. Even now the memory prompted a flare of anger. At seventeen, he and Oskar – all those young men – should have been full of hope. Instead, all they’d had to look forward to was endless months training for the threat of invasion by Western imperialist forces – and then what? Martial law, curfews and rationing … the dreary realpolitik of the socialist dream.

Oskar waved a pudgy hand at the table where his dawdling workers had sat. ‘Seriously though,’ he said, ‘these kids don’t know how easy their life is these days. Do they have any idea what site work was like here in the eighties? Twelve-hour shifts, no “health and safety”. Never mind an hour off for lunch, we didn’t even get a fucking tea break.’

Janusz grunted his agreement. ‘And if you wanted goggles or ear defenders, you had to buy them yourself,’ he said, tearing apart a piece of bread.

Oskar used his sleeve to wipe a porthole in the condensation of the window and peered out at the traffic. ‘Remember that chuj,’ he mused, ‘The Paddy foreman on the M25 job – the guy who treated us like dogs?’

‘The one whose thermos you pissed in?’ asked Janusz, raising an eyebrow.

‘Yeah, that’s the one,’ said Oskar, a beatific grin spreading across his chubby face.

‘Fuck your mother,’ he said, peering at Janusz’s plate. ‘What is that shit you’re eating?’ – then, to the girl who had just arrived to take his order – ‘The bigos for me, too, darling. It looks delicious.’

After she had left, Janusz finished his last mouthful and pushed the plate away. ‘Too much paprika, perhaps, and the duck was a little overcooked, but not bad,’ he said with a judicious nod. He pulled out his box of cigars, then, remembering the crazy no smoking laws, reached for a toothpick instead.

‘Listen Oskar, I still want the booze, but I’ve got a problem. Any chance of you waiting a couple of weeks for the cash?’

Oskar, mouth full of good rye bread, mumbled: ‘Don’t tell me – that donkey Slawek made a kutas of you?’

He helped himself to a slurp of Janusz’s lemon tea, shaking his head. ‘I can stand you half a dozen cases, mate, but not much more than that. I’ve got no slack right now.’ A secret smile crept along his lips. ‘I just sent five hundred home so Madam can buy a new living room carpet.’

‘I thought you were saving up so you could go home for good?’ said Janusz. ‘You’ll be here for ever if you let Gosia spend all your smalec on carpets.’

Oskar belched philosophically. ‘Like my father used to say: “The woman cries before the wedding; the man after.”’

The girl put a plate of bigos in front of Oskar, whose eyes rounded with childlike greed. ‘Duck!’ he exclaimed indistinctly through his first mouthful.

Ever since Janusz had known him, Oskar had worked like a navvie to support Gosia and the kids. They had slogged together through the night building motorway bridges in the eighties – back-breaking twelve-hour shifts – but come next day’s rush hour, when Janusz was still in bed, Oskar would be standing in a lay-by on the A4, flogging hothouse roses to motorists heading home. Even now, alongside his job as foreman for one of the biggest Olympic site contractors, he still found time for what he called his ‘beverage import business’.

It amounted to half a dozen clapped-out Transit vans that plied the cross-channel ferry routes, bringing in cases of cheap booze and cartons of cigarettes to sell on to traders like Janusz. The bottles of spirits ended up on optics in private clubs where no one questioned the ‘NOT FOR RESALE’ label, especially since the bottles carried another reassuring promise: ‘EXPORT STRENGTH’.

‘Listen,’ said Oskar, with a mischievous look, ‘if you’re short of cash, I could always get you a shift on the site.’ Dropping his fork he grabbed Janusz’s hand, and turning it over to check the palm, chuckled. ‘Kurwa! All this wheeling and dealing’ – he used the English phrase – ‘gave you hands like a schoolgirl’s! You wouldn’t last five minutes on a real job.’ He scooped up another tottering forkful of bigos. ‘You want to come over later, watch some football?’

‘I can’t tonight,’ said Janusz. ‘I’ve got a ticket for a lecture at the Royal Institute – one of the physicists from the CERN project.’

Oskar frowned. ‘That big metal doughnut in Switzerland – the one that keeps blowing a fuse?’ he asked. ‘Something to do with the First Bang?’

Janusz nodded – it was easier.

‘They say the universe will collapse one day, you know,’ said Oskar, adopting a scholarly air. He clapped his hands to demonstrate: ‘Pfouff! Down to the size of a beach ball.’ Before he could offer any further cosmological insights, the café door rattled open to admit three lanky buzz-cut youngsters, dwarfed by their rucksacks. Their loud voices exuded confidence, but the way the trio hung close together, shoulders almost touching, told the real story. First-timers, thought Janusz, straight off the 0830 Ryanair flight from Warsaw. When the tallest one spotted Oskar his relief was palpable.

Joining the men at their table, the boys greeted them politely. Oskar balled his checked napkin and after wiping the grease from his lips, punched out a number on his mobile.

‘Czesc, Wassily, you old hedgehog-fucker,’ he bellowed. ‘You still looking for ground-breakers? I’ve got three beauties for you – real musclemen.’ He winked at Janusz. The youngsters exchanged apprehensive glances, shrugged. ‘I’ll bring them over now.’

Oskar levered himself up from the table on powerful arms with a sigh. ‘Some of us have man’s work to do,’ he told Janusz. ‘I’ll put your name on a dozen cases, kolego, but if you can get cash for more by tomorrow, let me know.’

Oskar departed, trailed by his clutch of new recruits, but at the café’s threshold he turned.

‘Remember what we used to say when we were skinny-arsed conscripts shivering in the barracks?’ he shouted to Janusz. ‘Life is like toilet paper …’

Janusz finished the saying for him: ‘… very long and full of crap.’

The rectangle of oak slid open and Janusz bent his head to the aperture.

‘I present myself before the Holy Confession, for I have offended God.’

He shifted in his creaking seat and coughed, a bassy smoker’s rumble. Through the wire mesh, he could make out Father Piotr Pietruski’s reassuring profile, topped by his unruly shock of white hair.

‘It has been, uh, three months since my last confession,’ he said.

‘Six, faktycznie,’ corrected the priest. ‘I did hope that we would see you at Midnight Mass, at least.’

‘I’m sorry, father. I’ve had a lot of … business to attend to.’

Unconsciously, he clenched his right hand, stretching the grazed knuckles white.

The priest tugged at his earlobe – it was a familiar gesture, but whether it signalled resignation, or exasperation, Janusz never could tell. He felt a surge of affection for the old guy: Father Pietruski had always looked out for him, from that first morning more than two decades ago when he’d showed up here after a 48-hour bender, rain-soaked, wild-eyed and stinking of wodka.

Back then, before every inner-city high street had its own Polski Sklep, homesick Poles had beat a path to St Stanislaus, hidden away down an Islington back street. English Catholic churches, all modern steel and concrete, were unappealing, but St Stan’s was solid, nineteenth century, its stone structure curvaceous as a mother’s cheek, and since the mass was conducted in Polish it had felt almost like being at home. And the shop in its crypt where you could buy real kielbasa, cheesecake and plums in chocolate, didn’t hurt either.

These days he wasn’t even sure he still believed in all the mumbo jumbo, so why did he still come? Partly, he supposed, because the church felt like the last remaining pillar of the old Poland, a place where respect and honour were valued above all else. Or maybe because he’d never forget how Father Pietruski had found the drunken boy a bed, fed him lemon tea, and later on, put him in touch with a foreman looking for site labourers.

Even if it meant the old bastard never got off his case.

‘Have there been any recent incidents of violence?’ asked the priest.

‘One scumbag who was beating his wife. She came to me for help.’

‘And?’

‘I like to help women. I helped her. He decided to get another hobby,’ Janusz shrugged, pressing a smile from his lips. Better not to mention the woman in question was his girlfriend.

The older man sighed. It was never straightforward with this one: his methods might be unsanctionable, but his instincts were often sound.

‘Anything else to trouble your immortal soul?’ Janusz detected a trace of sarcasm.

‘Sins of the flesh, father.’ A sudden image: a rumpled bed, the rosy S of a woman’s naked back, Kasia’s, framed by an oblong of light. ‘The normal things.’

‘These “things” are not normalne. You are a married man: that sacrament is indissoluble!’ The priest actually rapped out each syllable with his knuckles on the mesh.

The old fellow had – unusually for him – raised his voice, stirring up a little rush of whispers from outside the box, where, Janusz knew, a bevy of old dears would be waiting to confess their imagined sins. Maybe the priest was right, but what was he supposed to do? He and Marta had read the last rites over their marriage long ago, and he wasn’t cut out to be a monk.