Полная версия:

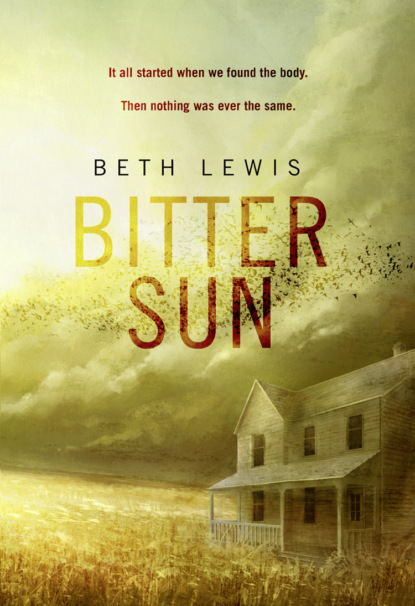

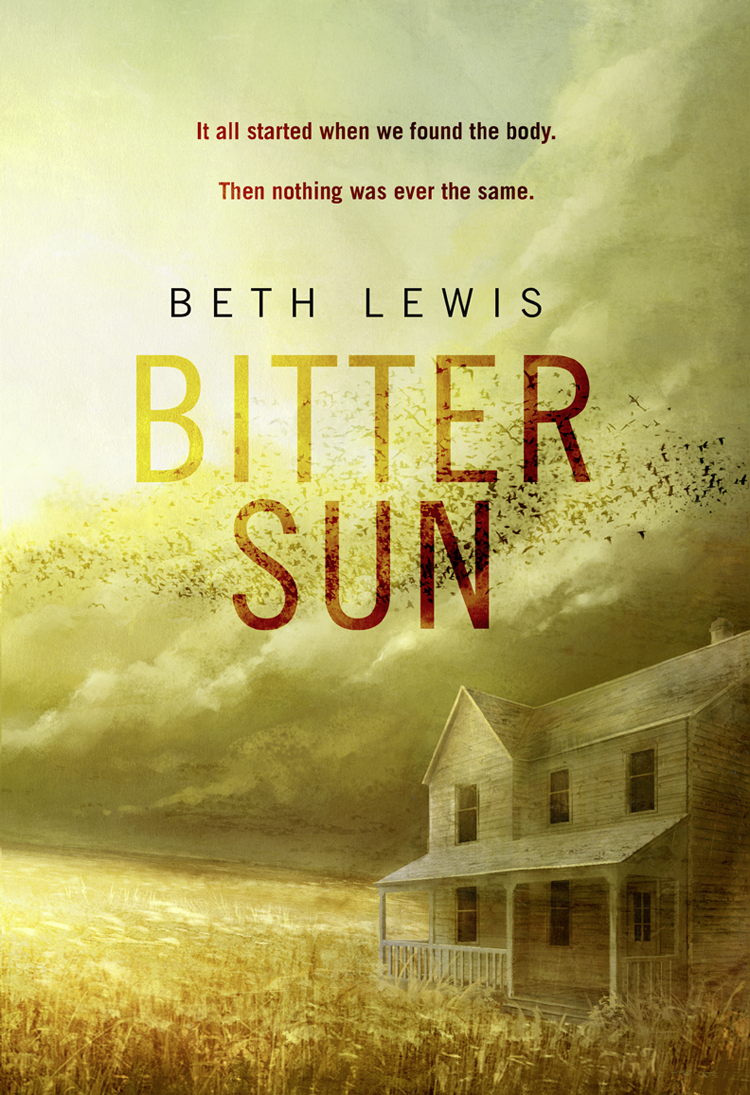

Bitter Sun

Copyright

The Borough Press

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Copyright © Beth Lewis 2018

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018.

Cover illustration © Alexandra Gurtner/Bridgeman Studio

Beth Lewis asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780008145507

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2018 ISBN: 9780008145521

Version: 2018-04-24

Dedication

For Neen

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

He walks broken …

Part One: Summer, 1971

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Part Two: Summer, 1972

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Part Three: Summer, 1973

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Acknowledgements

Loved Bitter Sun? Enjoy another incredible literary thriller from Beth Lewis …

About the Author

Also by Beth Lewis

About the Publisher

*

He walks broken. Barefoot in the dust. Middle of the road, asphalt shimmering in the heat, he walks like one of the returning soldiers. The ones with plastic legs. Limp. Shamble. Limp. Shamble. He’s too young for the jungle so he’s here. On the long road to town, rimmed with cornfields. The stalks heavy with gold on one side. Mangy and rotten on the other. A good year and a bad year, shoulder to shoulder.

He’s forgotten his name.

Smoke streaks across the asphalt from burning fields. Driving away the blackfly and maggots, refreshing the soil with ash. Next year will be better, they’ll say. Next year we’ll forget this ever happened.

He’s forgotten his home.

His t-shirt flicks in the breeze. Scarlet smears across his chest and arms, diluted to pink and brown at the hems. Thick blood thinned by dirty water.

A car slows, then swerves when the driver sees the blood. Foot down hard on the gas. Gone into a cloud.

The dust coats his skin and prickles his eyes but he doesn’t feel it. The road is too long, stretching endless. Sharp gravel digs into his bare soles. Threatens to cut.

His head sways side to side with every step, a metronome without its tick.

The blood, on his arms, his stomach under his shirt, his legs down to the knees, feels tight and sticky.

He’s forgotten his family.

A horn blasts behind him. A truck sidles alongside. He never heard it coming. A man leans across the empty passenger seat and winds down the window.

‘Hey, you.’

He wavers at the sound of another person.

‘Hey, don’t I know you?’ the driver says. ‘Are you all right, son?’

The voice, the life, pulls him. He turns but doesn’t see. His vision blurred by grit and glaring sun and exhaustion. He opens his mouth but the words seem to come from another throat. The air to make them from another chest. The brain to form them from another head. An innocent head. Three simple, perfect words float off his tongue and into the truck.

‘I killed her.’

1

It was a heatwave summer when I was thirteen. A record breaker so they said. Momma, my sister Jenny, and me lived on a small farm a mile from town. A house of faded whitewash boards and a three-step porch in an ocean of cornfields. Oak tree in the yard with a rope hanging off its fattest limb. Used to be a tyre on it, one from the front of my pa’s tractor, but it broke last year and he was long gone by then so the rope frayed and rotted and turned grey.

Momma had let the farm overgrow in the six or so years since he left. Gone to the war, she said, and never told us more. She said the land was his and the house was hers and she didn’t give a rip about our cornfields, stunted and choked with ragweed. She made our money elsewhere, though I was never sure where. I did my best to keep the fields tidy, the corn planted and harvested, but it was only me working so the haul was always small. Still, last harvest I managed to sell the crop to Easton’s flour mill for a good price and bought myself a new pair of boots and Jenny a jump rope.

It was a Friday, a few weeks before school let out for summer, that we found it, me, my sister and our friends Rudy and Gloria. Larson had dressed up to the nines for Fourth of July on Sunday, all ticker tape and flags and red, white and blue. There would be a parade, floats and cotton candy and corn dogs, then the fireworks would light up the sky. Every year Al Westin set up a shade outside his grocery store to give out free ice cream cones to the younger kids and the Backhoe diner threw open its windows and played Elvis and Buddy loud onto Main Street.

Larson was one of a hundred small towns in the middle of the Corn Belt though it was on its way to being something more. Just last week a 7-Eleven shot up in the trodden-down, boarded-up laundromat, giving the place new life and a brisk trade that upset Al Westin. We’re a flyover town in a spit-on state, Rudy always said. But that was his daddy talking. Larson was full of good people who smiled on the street and wagged a finger if you dropped a gum wrapper. There was a carnival every year, the school just got a gleaming new yellow bus and the church had a fresh, young pastor who took the class for snow cones after Bible Study when it was steaming hot. We’re a big-heart town, Mrs Lyle from the post office would say.

Eight in the morning, before the sun revved up its engine, Jenny and me walked the mile to school. I carried her book bag while she skipped ahead and sang and then screamed when I chased her and when I caught her we laughed. Momma didn’t much like us going to school. She said it made pansies of men, made their heads soft and their hands limp. Too much holding a pen, she said, not enough holding a woman.

But school was our sanctuary, a place full of friends and learning, and there was Miss Eaves. She taught geography two hours a week, after lunch on a Monday, last on a Friday. Best part about the class was me and Jenny took it together. Jenny was a year younger but the middle school wasn’t big and both years fit in the same room. We had desks next to each other. We passed notes.

Jenny loved all those countries, languages, people, currencies; pesos, francs, dirham, lira, exotic to the ear. She was obsessed with the pictures of buildings older than anything in Larson, older than anything in our United States, and her enthusiasm was infectious. That class opened up our world, made us four want to get out of Larson, get out and see it all. Though for me, that desire to up sticks stayed in the classroom, for the others, it was constant, like breathing. I loved that class for the lessons on soil and agriculture and how they grew rice in China or coffee in Brazil. I’d be running the Royal farm one day so I sucked in anything and everything that might be useful.

Miss Eaves hushed the class, clicked her fingers for us to sit down. We called her Miss but she was a missus four times over, skin and bone but somehow soft. Jenny liked her. She said Momma was all odd angles and sharpness but Miss Eaves was a cloud of cotton candy, sweet-smelling like inhaling powdered sugar. The skin on her hands was folded and sagged like a bloodhound’s cheeks. She had been a big woman once, she’d told me after class once, but lost it all when her fourth Mister went off to war in ’68. Said she couldn’t eat without anyone to eat for. Momma called her loose and unnatural, four Misters and no babies? What kind of woman is that?

Everyone else in class was goofing off, Jenny giggling with Gloria and Maddie-May, Rudy shooting spitballs at the back of Scott Westin’s head, but I was quiet. I didn’t have the energy to horse around. It’d been too hot to sleep for the past week and we didn’t have one of those fancy central air units like in Gloria’s house. Jenny and me shared a room and a bed up in the attic where the heat stuck. We made shadow puppets and butterflies with our hands and made them dance. I told stories of far-off kingdoms, and she’d pretend to be the princess while I roared as the dragon. Momma never woke to tell us to keep the noise down. Whiskey was her bedmate and not much could rouse her. When we were too tired to play, Jenny would ask for a story, then drift off to sleep when I was barely halfway through.

That Friday, with the world turned up hotter than the Backhoe fryers, flies circled and swooped on the ceiling. We made fans of our exercise books and shifted desks to escape direct sunlight. Poor Benjy Dewitt who sat closest to the window got scorched, blisters bubbled all up his left arm. Sweat and steam rose off us, turned the chalk dust to paste and smeared ink. Even Miss Eaves was struggling. Mid-way through a talk on volcanoes, when the breeze died and the classroom started to smell keenly of sweat, she stopped, threw her notes aside and said that magic word, ‘dismissed’.

‘Get out, the lot of you, go cool down,’ she said.

When we didn’t move, she clapped her hands together and shouted, ‘Hustle, hustle!’

Let out early. On a Friday. The class erupted and spilled out of the room, out of the school. Me, Rudy, Gloria and Jenny didn’t tell our parents. Momma wouldn’t care but Rudy’s dad would make him clean car parts in the salvage yard and Gloria would have to practise her piano and painting an extra few hours. I had a dozen jobs to do on the farm but we had a free hour or so to spend together and I wasn’t going to waste it on chores. We just wanted to run, arms wide like we were flying. We’d be like ducks taking off from a pond, powering their feet, getting lift and height and then up, up, up, into the blue, soaring higher where nothing mattered and nothing could touch them. That was us. That was summer.

The four of us were gone, out into the sun and through the fields to the Roost. A place that was ours and ours alone. It was a wooded valley, our dip in the world, with a narrow but deep river running through it, thick with laurel and brush and creeper vines, grown dense and high like the sides of a bird’s nest. In the Roost we’d built a shack, our Fort. We’d added to it since we were six and seven and now it was a grand structure. The roof was a square of sheet iron Rudy lifted from Briggs’ farm when the old man pulled down his cattle shed. Walls were a dozen new planks left over from when they repaired the post office after Darney Wills, sodden drunk, ran his father’s truck through the front window. Then we had a broken doorbell and handle, all ornate gold scrolling on the edges, Gloria got from her father when they replaced it last year. That gave us a touch of class, we all said.

We always covered the path down to the Roost with branches. It was a narrow opening between thick shrubs and trees so was easily concealed. It was far off the roads, in the middle of fields, but we wouldn’t take any chances. It was Rudy’s idea to keep it hidden. This is a peachy spot, Johnny, he said, and we don’t want any old yahoo knowing about it.

But that Friday, the branches were thrown aside.

‘Did we …’ Gloria started, no doubt meaning to say, ‘Did we cover the entrance the other day?’ but we all knew we had.

‘You think someone …’ Jenny trailed off too.

Gloria picked up a branch, held it like a baseball bat. ‘Do you think they’re still down there?’

‘I can’t hear anything,’ I said, and found a stick too.

Rudy picked up a branch shaped like a club and rested it on his shoulder.

‘Jenny, you stay up here.’

My sister scoffed and grabbed a stick of her own. ‘Hell to that. I’m coming too.’

Rudy grinned and saluted, knocking his heels together like he was in front of the Queen of England.

Rudy tested out the weight of his club, swiping at nettle heads until he cut one clean off.

‘Ready?’ he said and we nodded. ‘No mercy!’

We barrelled down the hill into the valley, Rudy hollering out his war cry like some mad general, me right behind, branch up and catching on the trees, the girls behind me screaming.

We charged to the Fort, expecting intruders to leap out and flee in terror or put up a fight at least, but the Roost was empty. Rudy stopped dead and I crashed into him, knocking us both into the dirt. A moment, a beat, while we realised we were alone and unhurt and had just yelled our throats sore at nothing, then we all four collapsed into howling laughter. We frightened nobody but the birds.

‘Check it out,’ Gloria said, the first to get up, dust herself off, and look around.

The Fort’s roof was bent, our door swung on one hinge. Inside was strewn with leaves and muck, the blanket we often sat on snagged on a nail and ripped. Someone had been here. Suddenly the laughter vanished and my chest tightened. But who knew about this place? Maybe a bum? One of those hobos who rides the rails and sleeps under trees like in the movies? Or some other kids from school, maybe Patrick Hodges or the Lyle boys, thinking this was unclaimed land? Did the fuckers wreck the place when they realised it was already taken?

It was a violation and we all felt it. The unrelenting, unending heat wasn’t enough, the world wanted us punished more. Maybe it was taking revenge on Rudy for stealing a pack of cigarettes from his father, or Gloria for skipping her piano lesson and making the teacher wait, maybe on Jenny and me for not being better at washing linens or placating Momma when she was in one of her tempers.

‘We should repair it,’ Rudy said, kicking a board over, insects fleeing in the light. ‘Soon as. Pick that up, clear it out and go get a rock to beat out the dents. It’ll look stellar again in no time.’

Everything was stellar to Rudy. Didi’s blueberry pie was stellar. Clint Eastwood, man, him and Telly were stellar. Swimming in Barks reservoir, now that’s stellar. Rudy was the oldest by four months and that was enough to make him our leader. A flash of his straight-as-a-die teeth and a flick of his sandy blond hair, cut like a movie star’s, and you can’t say no.

I picked up the board he’d kicked. One from the post office. It was heavy, covered in mud, and he bent down to help. To most in Larson, Rudy was the bad kid, the prankster, the you-won’t-amount-to-anything boy from the Buchanan family of cons and thieves, but to me and Jenny and Gloria, he was goodness made bone and skin.

The girls set about tidying the inside, repairing the blanket, setting the cobbled-together table and mismatched chairs and tree stumps right. I found a heavy rock for knocking the dents out of the roof.

‘We’ll need more nails, and a hammer,’ I said.

‘I’ll get some from McKinnon’s hardware,’ Rudy said. ‘Got a few bucks saved up from cutting his grass last summer.’

Rudy hoarded money, his Larson escape fund. Even Jenny had a few nickels under her pillow. Seemed like every kid had one, except me. I had money saved up but it wasn’t for a bus ticket, it was for old man Briggs’ second tractor. He’d promised to sell it to me when I had the cash and could reach the pedals. I was one-for-two but that kind of money is hard to come by around here. I’d have it though, one day, you can bet your weekly on it.

We straightened up the roof and rehung the door and by that point, the sun and heat had eased and we’d forgotten that anyone else had ever been here.

Rudy and Gloria were over by the lake when Jenny came out the Fort saying she was hungry.

‘I’m craving some fishes, Johnny.’

I smiled at the way she said ‘fishes’, the way her mouth puckered up at the sh sound.

‘Get the poles,’ I said. ‘Perch’ll be running about now.’

Jenny jumped and clapped and rushed back in the Fort to get the poles. They were nothing much, just saplings and line, but they were ours and they kept us fed. Friday meant Momma would be in Larson, at Gum’s Roadhouse, shooting pool and tequila. No dinner on the table. No one looking for us. Sometimes we stayed out here all night, lit a fire, slept in the Fort, watched the sunrise over the fields.

Summer before last we’d dammed and diverted the river a few hundred yards upstream from the Fort where the land dipped in a natural, deep curve. It was Rudy’s idea. Everything was Rudy’s idea and no matter how sky-high crazy, they always felt like good ones. It’ll be our own private swimming pool, Johnny, he’d said, ten times better than Barks because it’ll be all ours. And it was up to me to make it work. I’d read a bunch of library books to make sure we got it right. It’d taken us months, all over that winter. Even when our hands were frozen and we had to dig out the planks and rocks from under a foot of snow, we kept building. By last summer it was full and we called it Big Lake. The water was clear and you could see all the details of the forest floor, like you were looking at a carpet through a glass table. In winter it froze solid and we’d ice skate and try to play hockey and fail. It was a thing of beauty, I always said. A place trapped in time, like when they flooded whole towns to build their hydro-dams. Houses and streets and rusted-up cars, all held as they were before the water came.

Last year, Rudy and me hung a rope on a strong laurel branch. Shame on us but we were too chicken to swing into the water, too stuck to run and fly and let go then get that sickening moment of falling and splash. What if there were rocks we hadn’t seen? Or sticking up branches that’d skewer us dead? I wasn’t the best swimmer in the world and everyone knew it so never expected me to go first, but even Rudy was afraid, though he joked it off. Jenny stood close by me, said she didn’t want to get her dress wet and, despite the heat, despite the cloying, sweating hotness of the world, all we did was dip a toe.

Except Gloria.

None of us were looking for her to be the bravest, the first. We took it as certain that she would go last, she was a girly girl, rich family type. But before Rudy could turn around and tease her for it, Gloria was sprinting. A blur of red dress and red hair as she ran for the rope, kicking up brown leaves, sending them skimming the water. I remembered her swinging high, letting go, shrieking and disappearing into the lake, then popping up like a mermaid, hair dark red and stuck to her head, laughing and calling us all sissies. From that day on Rudy said you can never be sure with Gloria. Momma thought the same when I told her the story. She’ll grow up to be a quicksand woman, Momma said. Careful of that one, John Royal, she’ll have you running circles you don’t even know about. Be the death of you, she will.

Gloria always did what nobody expected.

So that Friday when we were fishing for perch in Big Lake, it was Gloria, wandering, not fishing because she thought it was boring, who found it. Tangled in the roots of a ripped-up sycamore, half-sunk in the flooded wood.

‘Come look,’ she shouted, stick in her hand for prodding. ‘Get over here the lot of you.’

Rudy, on the other side of the lake, ran.

Jenny trailed behind me. ‘But the fish, Johnny.’

‘It’ll just take a minute. Hook’s in the water anyways.’

Gloria pointed with her stick. It was just out of arm’s reach, the thing in the roots. But it wasn’t a thing. The closer I got the clearer I saw. Rudy stopped running. He saw it too. Gloria’s face was frowning and pale. Rudy looked back at me with hard eyes that said, keep Jenny back. It wasn’t real, it couldn’t be, not here. It was grey skin and hair once blonde like Rudy’s. It was bloated but not unrecognisable. Gloria’s stick left impressions in the skin.

It was a woman and she was dead.

2

We didn’t tell anyone about the body, at least not at first. A mixture of fear and fascination silenced us. It fizzed inside us, this knowledge, this secret, so colossal and strange we thought it would crush us if we put one toe wrong, one word in the wrong ear.

The four of us stood silent and staring for I don’t know how long. Just as dusk was settling and the starlings began their wheel, we decided to pull the woman out of the water and roots and lay her alongside a fallen tree trunk. We thought it kinder, to have something at her back, some comfort.

The woman, in my head I named her Mora, for the sycamore tree, was the first I’d seen naked. Mora’s were the first breasts, the first swatch of hair between the legs, the first bullet hole.

Gloria couldn’t look at her. Jenny couldn’t stop.

Rudy swore in a whisper and leaned into me. ‘What do we do?’

But I didn’t have an answer.

‘Who do you think she is?’ Jenny said but nobody wanted to guess.

‘We should tell Sheriff Samuels,’ Gloria said and I heard a tremor in her voice. Usually so steady, her tone, rich like knocking on oak, shook at the sight of death. Rudy was quiet, a deep frown clouding his eyes, as if were he to concentrate hard enough, he would bring a storm rolling across the cornfields.

‘Not yet,’ I said. It was a terrible secret, I realised. One that could change everything, and I didn’t know what to do. I wanted to run home, to Momma. She’d know how to handle it, what to say, she always knew best, but I was rooted. Momma wouldn’t be home this time on a Friday night and, besides, how could I explain it?

Jenny stepped closer, looked at Mora as if she’d come upon a rat snake taking in the neighbour’s dog. The serpent’s jaw dislocating and reshaping itself so unnaturally. Something that small ingesting something far too big, you can’t help but watch, a jumble of curiosity, revulsion, an urge to help surpassed by a want to know if it would succeed in its swallowing. I’d never seen that expression on Jenny’s face before. Something happened to her that day. Changed her from the girl who would lazily kick her feet in the river, breathing in the sun and scent of evening primrose, to a girl who couldn’t sit still, as if she had electricity running through her, twitching her muscles, itching beneath her skin.