Полная версия:

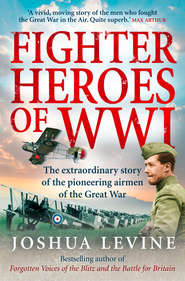

Fighter Heroes of WWI: The untold story of the brave and daring pioneer airmen of the Great War

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road,

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2009

Copyright © Joshua Levine 2008

Joshua Levine asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007274949

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2014 ISBN: 9780007374069

Version: 2014-08-15

Dedication

For Dorothy Sahm

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

Prologue: December 1917

1 Emulating the Birds

2 The Combatants

3 A Flying Start

4 And so to War

5 An Office Job

6 Fighters and the Fokker Scourge

7 Life and Death

8 Over the Top

9 Bombing and the Royal Air Force

10 A Fight to the End

Epilogue

Picture Section

Keep Reading

Searchable Terms

Acknowledgements

Archived Sources

About the Publisher

Introduction

There are certain historical subjects which can always be counted on to capture the public imagination. One of these is infantry fighting on the Western Front, with its vivid evocations of suffering and wasted life. Yet taking place above the very same Western Front was a conflict that is less well known, but which deserves to become just as embedded in the public consciousness – the Great War in the Air.

Most people will have heard of Baron von Richthofen, but they will have little idea of why he was flying or who he was flying against. Yet the story of air fighting is one of intense human emotion, of young men growing up quickly in an exciting and terrible world, of chivalry and fear and danger, of the creation of modern warfare, of the development of modern sensibilities. Such an extraordinary story deserves a wider audience, and an acknowledgment of its place in history.

In 1976, it began to reach that wider audience when the BBC broadcast a television drama called Wings. Set in a Royal Flying Corps squadron in 1915, its central character is a young blacksmith who becomes a sergeant pilot on the Western Front. It is a moving series, which portrays the lives of young men attempting to make sense of a strange and terrifying world – and that is exactly what this book tries to do; to place individuals in the foreground who can paint detailed pictures, whilst never losing sight of the chaos erupting in the background.

Whilst writing this book, I have discovered how vivid and evocative a world it can be; I have found myself immersed in it – in its diaries, novels, letters, memoirs, aircraft, people, and sensibilities – only returning to the twenty-first century to pay the occasional bill. I hope that you, the reader, find yourself similarly engaged (not perhaps to the detriment of your household finances) so that the exploits of Mannock, Ball, James, Powell, and many others, become important to you. It is easy to identify with these recognizably modern men, carrying out a modern activity, with surprisingly modern attitudes, from a time long gone.

Whilst the time may have gone, one of its inhabitants is still with us. Henry Allingham, 111 years old as I write, served with the Royal Naval Air Service on the Western Front and at Jutland. He is a Victorian by birth, who has watched troops return from both the Boer War and the Second Gulf War. He has outlived many comrades by over ninety years, and he is the sole founder member of the Royal Air Force still alive. In the year of its ninetieth anniversary, it is fitting that we should remember the men who came together, some willingly, others less so, to form the Royal Air Force, and equally fitting that we should remember the thousands of airmen who died as it came into being.

In the pages that follow, the thoughts, feelings, fears and sensations of long ago are aired. Listen to them, and enter a world quite different to our own – inhabited by people not so very different at all.

JOSHUA LEVINE

PROLOGUE

December 1917

“Some time after the Cambrai attack in 1917, my scout squadron, No. 3 RFC, which was equipped with single-seater Sopwith Camels, each carrying two Vickers guns firing through the propeller, was stationed near Bapaume, and was manned by comparatively new pilots with no combat experience to speak of, as the squadron losses in the Cambrai battle had been complete, with the exception of two pilots – myself and a Captain Babington.

One day after the two flights, ‘A’ and ‘B’, the latter under my command, had been detailed to carry out a routine patrol over the enemy lines, I remember walking across the worn grass on a bright sunny morning towards our eight machines lined up in front of the hangars. The air mechanics were standing by as usual after having very carefully checked over guns and engines. They helped us into our cockpits and saw us settled in our seats and safety belts fastened, then they climbed down with a quiet, ‘Good luck, sir.’

It was only then that the tension that was always present just before taking off on a patrol left us and we were able to think of our immediate duties. After having repeated the mechanics’ ‘Contact!’, our engines roared into life and we all revved them up against the chocks with the mechanics holding down the tail to check that we were getting full revolutions. Then I throttled down and after a glance round the flight to see that all were ready, I taxied into the wind and took off, closely followed by the whole patrol.

We climbed to cross the trenches a few miles away at 12,000 to 13,000 feet, and while doing so, fired a few rounds from both of our guns to make sure there was no jamming as this was very difficult to clear while in action. Our Camels being tail heavy, the stick had to be held between our knees to free both hands to clear the stoppage, otherwise the planes immediately shot up into a loop. The trenches beneath us wound like long scars meandering across the seemingly lifeless dun-coloured countryside, pitted with thousands of shell craters, not a single tree or building left standing anywhere near the lines.

Very soon, we heard and saw our usual welcome from ‘Archie’, bursting in black puffs all around us, but carried on, only varying our height to spoil his aim. After crossing the lines without further incident, we found that the fresh wind, which always seemed to blow to the east, was drifting us too far into enemy territory, and it would have been unwise to penetrate, our limit of flying time being only two hours: a return slow flight against the wind under possible attack might have exhausted our petrol before it was possible to reach our landing field. I therefore gave the signal to turn north, parallel with the trenches, and we continued our patrol.

Just then, several thousand feet above us and right in the sun, I saw a formation of sixteen enemy aircraft (we were always outnumbered) and in a few seconds they were diving on our formation from all directions, and the air was full of tracer, and twisting and turning machines, engaged in a general dogfight. One of ours was soon in difficulties and was seen to go down, out of control, at the same time as two of the Huns also broke off, apparently badly damaged. We closed formation again with ‘B’ Flight still intact, followed by two of ‘A’ Flight, and waited for the next assault, as the Germans had dived past us after their first attack, and were now gaining height again. They were a squadron of Richthofen’s Circus, and they were painted in all sorts of colours and patterns, and one, I noticed, had a wavy red snake painted along the fuselage. But there was not much time to wonder at them, as part of their squadron had been kept in reserve a few thousand feet above: their Albatroses could always out-climb and out-dive our Camels, as they had beautifully streamlined plywood fuselages and powerful engines, while our machines were still at the fabric-covered wooden-framed stage, with rotary engines.

These Huns came down at us and one of ‘A’ Flight was soon in difficulties, being surrounded by at least three of the enemy, and fighting hard against such odds. To go to his assistance was, of course, the only thing to do, and by waggling my wings from side to side, I gave the one signal we could use in those days in an emergency, for the rest of the flight to follow. But in all the excitement and tension, my turn to the right was not noticed, and I realised that I was single-handed in the rescue attempt, and would have to deal with four Huns, as by the time I reached the scene, our machine was already going down practically out of control, and I was quickly in a dogfight with three highly coloured Albatroses.

I picked on the one which seemed to be piloted by the leader as it had a small triangular black flag attached to the vertical fin of his rudder, besides being vividly coloured. We engaged in the usual circling tactics, each trying to out-turn the other and keep on the inside, and in this manoeuvre, I was successful owing to the remarkable turning property of the Camel, and I held the inside position with my guns aimed at the front of the Hun machine. We were so close that I could clearly see the pilot’s white face with his goggles and black flying helmet, looking over the side at my machine, and although I fired several short bursts, I could see all my tracers swinging to just miss his tail. My Camel was very near to the limit of its turning circle, but I realised that I had to turn just that little extra in order to rake his fuselage with my fire.

We had been circling for what seemed like hours but must have been only minutes, when I pulled the Camel still further round on its left hand turn, and loosed off a long burst which hit just behind the pilot, and put his machine out of control. We both fell away, myself in a fast full-power spin. By this time, three other enemy aircraft had climbed above us, waiting their chance, and I realised that as I came out of my spin, I would present a good target on straightening out in a vertical dive.

After falling about a thousand feet, I stopped the spin, and immediately did a fast turn and climb to face two of the diving enemies as they came at me, their tracers crackling past and my guns replying, but all without apparent effect. The two Huns had dived past as I turned to meet the third machine which was following the first two, and I noticed his painted red nose and blue fuselage, and realised too late, that he had a bead on me. A frantic pull over on the joystick was also too late, and the next thing I knew was a stunning sledgehammer blow as a bullet sunk into my right thigh.

Recovering from the shock, and finding the Camel in a vertical climb through the instinctive pulling back of the stick after being hit, I pulled over hard into a quick roll, just in time to miss a burst from a diving Hun, who was waiting above. It must have been about this time that my feed pipe was partly shot through, and the escaping petrol started spraying over my right leg, making it numb and cold, but my worry now was how to get out of the fight alive, and reach our lines again.

Three Huns were now following me down in a steep dive, firing as they came, but when any of them approached too close, I pulled the Camel into a vertical climb, and fired bursts at the nearest, then turned and dived again towards our lines, still some miles away. These manoeuvres continued in a running fight for a long time, and I began to feel a little sick through loss of blood, especially when my leg felt hot and warm instead of cold, through blood running down from my wound overcoming the previous numbness.

With all these odds against me, there suddenly came the realization that these Huns were out to kill me without mercy or hesitation, crippled as I was, and the enormity of it momentarily created the thought that just by turning towards enemy territory, this fate could be avoided, and I should be saved from further suffering. Perhaps some feeling of pride overcoming the indignity of the suggestion enabled me to regain my self-control, and to continue the running fight towards our trenches, losing height and turning every now and then to face and drive off my attackers.

Down to about a thousand feet, and feeling pretty weak, I managed to find a stick of chewing gum in my flying coat breast pocket, and I ate that, paper and all. The Huns followed down to 500 feet, just above their trenches, and then turned away as I crossed our lines at 200 feet, making for one of our emergency landing fields, containing a hut and one air mechanic on duty.

With some difficulty, as I could not see very well, and my Camel was badly shot up, with most of the flying wires cut and dangling, I made a fair landing, and was helped out by the airman. In getting out, I could not help noticing a neat group of four bullet holes in the cowling behind my seat, and about two inches behind where my head had been; an inch or two further to the rear and this burst would have hit my petrol tank, and what we all fear most – to be set on fire in the air – would have happened. And there would have been no escape, parachutes for pilots not having been issued.

Why those bullets should have missed me is one of the unsolved mysteries of my life; some lasted a few weeks, others months, one never knew. So often had I packed up my roommates’ belongings, always left ready in case, and forwarded them to relatives, wondering when my own turn would come. Now it had – and more fortunately for me than for most of these young pilots.

The airman soon had a stretcher party along which took me to an advanced dressing station, where my wound was dressed, and a day or two later, I was on my way to Rouen, then back to London. After some two months in hospital, convalescing, I was posted to a training squadron as flying instructor, and only returned to active service just before the end of the war.”

Howard Brokensha

1

Emulating the Birds

If you happen to be reading this book on board a commercial flight, take a look around you. You are sitting in a pressurized cabin. You have no real sense of movement and you probably have no view. Your fellow passengers are eating and drinking, reading and sleeping. Unless they are nervous flyers, they are unlikely to be reflecting that they are breaking the laws of nature and defying common sense. The ‘wonder of flight’ is in short supply on the transatlantic run – but it has not always been so. In 1915, Duncan Grinnell-Milne was a young officer serving in the Royal Flying Corps. On a BE2c reconnaissance flight over the German lines in that year, in the midst of the bloodiest war ever fought, he experienced an overwhelming sensation:

I must be asleep, dreaming. The war was an illusion of my own. Surely the immense and placid world upon which I gazed could not be troubled by human storms such as I had been imagining. In that quiet land human beings could never have become so furiously enraged that they must fly at each other’s throats. At 10,000 feet, on a sunny afternoon, with only the keen wind upon one’s face and the hum of an aero-engine in one’s ears, it is hard not to feel godlike and judicial.

In flight, the normal yardsticks that apply on the ground are suspended. Perceptions of speed and distance are altered. Mountains, rivers, urban sprawls, even battlegrounds lose their significance. This is why man has always dreamt of flying: to distance himself from his human frailty and place himself closer to the mysteries of the universe. Yet the godlike sensation felt by Grinnell-Milne also encourages a sense of power. The desire to fly has long been accompanied by the urge to dominate. In 1737, almost 200 years before powered flight, the poet Thomas Gray imagined the sky as a battlefield on which England could affirm her superiority:

The day will come when thou shalt lift thine eyes

To watch a long drawn battle of the skies,

And aged peasants too amazed for words,

stare at the flying fleets of wondrous birds.

And England, so long mistress of the seas,

Where winds and waves confess her sovereignty,

Her ancient triumphs yet on high shall bear

And reign the sovereign of the conquered air.

In 1907, before a truly reliable aircraft had even been constructed, H. G. Wells was already predicting how the new technology would be used to wage war. In The War in the Air, described by Wells as a ‘fantasia of possibility’, he imagines a future conflict in which New York is destroyed by bombs dropped from German airships. The city becomes a ‘furnace of crimson flames, from which there was no escape’. The central character, a young British civilian, witnesses the devastation, recognizes that national boundaries no longer exist and awaits the collapse of civilization. We still await the collapse of civilization, but Wells’ predictions have proved more than mere fantasias of possibility.

On 17 December 1903, however, no such thoughts were in the minds of Orville and Wilbur Wright, bicycle shop owners from Dayton, Ohio. On that morning, at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, a site chosen for its forgiving sands and coastal breezes, Orville flew the first aircraft, powered by a tiny petrol engine. The Wright Flyer harnessed the wind and struggled into the air. It flew a distance of 120 feet at a height of ten feet. The brothers believed that the key to successful flight was control of an inherently unstable machine and that the key to control was to copy a bird in flight by warping (or twisting) the machine’s wings. As the wings were warped, the end of one wing would receive more lift than the other and that wing would rise, banking the machine and turning it in the direction of the other. In this way, the machine could be guided onto a particular course, as well as returned to stable flight when tipped by a gust of wind.

Over time, the Wrights improved their machine until, on 5 October 1905, Orville flew twenty-four miles at a speed of thirty-eight miles per hour. The brothers remained quiet about their achievements, commenting that of all the birds, the parrot talks the most but flies the worst. In fact, they were nervous of competitors discovering their secrets. They carried out no flights in 1906 and 1907, on the advice of their attorney, as they attempted to sell the machine to military authorities across the world. They were charging $250,000, but refusing to give a demonstration until a contract was signed. Unsurprisingly, nobody took up their offer.

In September 1906, the first machine took to the air outside the United States, flown by Alberto Santos-Dumont at Bagatelle, near Paris. French aircraft designers began to make impressive progress and they were soon claiming world records for flight duration and distance. They were unaware of the advances made by the Wrights, however, so when, in August 1908, Wilbur demonstrated the Wright Flyer at Hunaudières, near Le Mans, his audience was astounded. Not only had he complete control of the machine, but he was even able to carry a passenger. French claims were quietly dropped. In July 1909, the Wrights finally sold their aircraft to the U.S. Army but in the years that followed they became mired in patent litigation, and their creative drive petered out. In 1946, James Goodson, a colonel in the U.S. Air Force, persuaded the elderly Orville Wright to attend a military conference in New York. The two men flew together. Goodson remembers:

The hostess on the aeroplane saw this elderly gentleman and she approached him and asked, ‘Are you enjoying the flight?’ and Orville said, ‘Yeah, very much.’ She said, ‘Have you flown before?’ He said, ‘Yeah, I’ve flown before.’ She said, ‘That’s great! Do you enjoy it?’ He said, ‘I enjoyed the first flight and I’m enjoying this one too …’

Once at the conference, Orville was keen to distance himself from the world of modern aviation:

In introducing Orville to the conference, Eddie Rickenbacker, the First World War ace, said in his usual flamboyant manner, ‘Today, we have fleets of aircraft flying to all corners of the world. We’ve brought the world together. We’ve just finished a war in which fleets of aircraft have destroyed the industrial potential of entire nations. Fifty years ago, no one would have believed this but two men – and two men alone – had a magnificent vision and we’re fortunate to have one of them here today. I give you Mr. Orville Wright!’ There was a standing ovation, and little Orville stood up. He said, ‘My name is Orville Wright.’ There was a blast of applause. ‘But that’s about the only true thing that Eddie Rickenbacker has said. Wilbur and I had no idea that aviation would take off the way it has. As a matter of fact, we were convinced that the aeroplane could never carry more than one passenger. We had no idea that there’d be thousands of aircraft flying around the world. We had no idea that aircraft would be dropping bombs. We were just a couple of kids with a bike shop who wanted to get this contraption up in the air. It was a hobby. We had no idea …’

Given the strenuous efforts of the brothers to sell their machine to a military bidder, Orville’s words might appear slightly disingenuous, but in their wake, designers across the world competed to produce faster and more reliable aircraft. In Germany, research was focused not on aeroplanes but on dirigible airships. The first Zeppelin had flown in July 1900 but it was not until 1907, prompted by the military authorities, that work began on a large-scale airship.

In 1908, the first flying machine took to the air in Britain. It was flown by an American, Samuel Cody. Cody, cowboy, actor, kite inventor, balloonist, aviator and eccentric, had arrived in Britain in 1901, bringing his Wild West stage show with him. Dolly Shepherd, a pre-war balloonist and parachutist, remembers being drafted in to act as his assistant:

Cody was a sharpshooter with long hair, pointed beard, great big hat and white trousers. He was quite a showman. When I met him, he was frustrated because he used to shoot an egg off his wife’s head and the night before, he had grazed her skull. ‘Don’t despair!’ I said, ‘I’ll take her place!’ I’d never even seen the show, but that night, I went up on stage, and he put an egg on my head and took aim. What I hadn’t reckoned for – his son came up and blindfolded him. I didn’t dare move but he shot the egg and all was well. The next day, Cody invited me to see his kites. He had to do the sharpshooting business and theatrical things to make money. But he was making his big kites in the great hall at Alexandra Palace.