Полная версия:

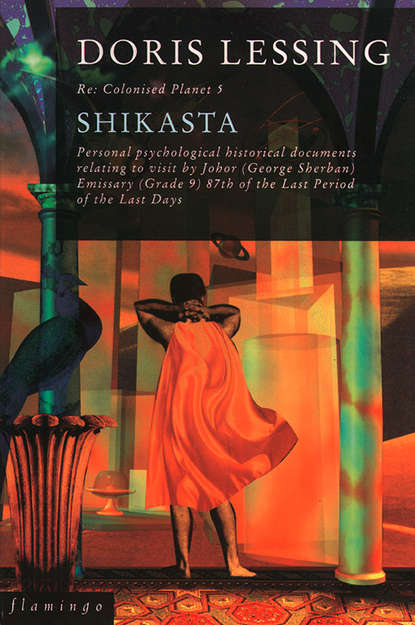

Shikasta

CANOPUS IN ARGOS: ARCHIVES

Re: Colonised Planet 5

SHIKASTA

Personal, psychological, historical documents relating

to visit by Johor (George Sherban) Emissary (Grade 9)

87th of the Last Period of the Last Days

DORIS LESSING

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape Ltd 1979

Copyright © Doris Lessing 1979

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780006547198

Ebook Edition © May 2012 ISBN: 9780007455539

Version: 2017-06-09

For my father, who used to sit, hour after hour, night after night, outside our house in Africa, watching the stars. ‘Well,’ he would say, ‘if we blow ourselves up, there’s plenty more where we came from!’

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Some Remarks

Shikasta

Keep Reading

About the Author

By the Same Author

Read On

The Grass is Singing

The Golden Notebook

The Good Terrorist

Love, Again

The Fifth Child

About the Publisher

SOME REMARKS

Shikasta was started in the belief that it would be a single self-contained book, and that when it was finished I would be done with the subject. But as I wrote I was invaded with ideas for other books, other stories, and the exhilaration that comes from being set free into a large scope, with more capacious possibilities and themes. It was clear I had made – or found – a new world for myself, a realm where the petty fates of planets, let alone individuals, are only aspects of cosmic evolution expressed in the rivalries and interactions of great galactic Empires: Canopus, Sirius, and their enemy, the Empire Puttiora, with its criminal planet Shammat. I feel as if I have been set free both to be as experimental as I like, and as traditional: the next volume in this series, The Marriages Between Zones Three, Four, and Five, has turned out to be a fable, or myth. Also, oddly enough, to be more realistic.

It is by now commonplace to say that novelists everywhere are breaking the bonds of the realistic novel because what we all see around us becomes daily wilder, more fantastic, incredible. Once, and not so long ago, novelists might have been accused of exaggerating, or dealing overmuch in coincidence or the improbable: now novelists themselves can be heard complaining that fact can be counted on to match our wildest invention.

As an example, in The Memoirs of a Survivor I ‘invented’ an animal that was half-cat and half-dog, and then read that scientists were experimenting on this hybrid.

Yes, I do believe that it is possible, and not only for novelists, to ‘plug in’ to an overmind, or Ur-mind, or unconscious, or what you will, and that this accounts for a great many improbabilities and ‘coincidences’.

The old ‘realistic’ novel is being changed too, because of influences from that genre loosely described as space fiction. Some people regret this. I was in the United States giving a talk, and the professor who was acting as chairwoman, whose only fault was that perhaps she had fed too long on the pieties of academia, interrupted me with: ‘If I had you in my class you’d never get away with that!’ (Of course it is not everyone who finds this funny.) I had been saying that space fiction, with science fiction, makes up the most original branch of literature now; it is inventive and witty; it has already enlivened all kinds of writing; and that literary academics and pundits are much to blame for patronizing or ignoring it – while of course by their nature they can be expected to do no other. This view shows signs of becoming the stuff of orthodoxy.

I do think there is something very wrong with an attitude that puts a ‘serious’ novel on one shelf and, let’s say, Last and First Men on another.

What a phenomenon it has been – science fiction, space fiction – exploding out of nowhere, unexpectedly of course, as always happens when the human mind is being forced to expand: this time starwards, galaxy-wise, and who knows where next. These dazzlers have mapped our world, or worlds, for us, have told us what is going on and in ways no one else has done, have described our nasty present long ago, when it was still the future and the official scientific spokesmen were saying that all manner of things now happening were impossible, who have played the indispensable and (at least at the start) thankless role of the despised illegitimate son who can afford to tell truths the respectable siblings either do not dare, or, more likely, do not notice because of their respectability. They have also explored the sacred literatures of the world in the same bold way they take scientific and social possibilities to their logical conclusions, so that we may examine them. How very much we do all owe them!

Shikasta has as its starting point, like many others of the genre, the Old Testament. It is our habit to dismiss the Old Testament altogether because Jehovah, or Jahve, does not think or behave like a social worker. H. G. Wells said that when man cries out his little ‘gimme, gimme, gimme’ to God, it is as if a leveret were to snuggle up to a lion on a dark night. Or something to that effect.

The sacred literatures of all races and nations have many things in common. Almost as if they can be regarded as the products of a single mind. It is possible we make a mistake when we dismiss them as quaint fossils from a dead past.

Leaving aside the Popol Vuh, or the religious traditions of the Dogon, or the story of Gilgamesh, or any others of the now plentifully and easily available records (I sometimes wonder if the young realize how extraordinary a time this is, and one that may not last, when any book one may think of is there to be bought on a near shelf) and sticking to our local tradition and heritage, it is an exercise not without interest to read the Old Testament – which of course includes the Torah of the Jews – and the Apocrypha, together with any other works of the kind you may come upon which have at various times and places been cursed or banished or pronounced non-books; and after that the New Testament, and then the Koran. There are even those who have come to believe that there has never been more than one Book in the Middle East.

7th November 1978

Doris Lessing

CANOPUS IN ARGOS: ARCHIVES

SHIKASTA

Johor has been chosen as suitable to represent our emissaries to Shikasta – of whom there were many, carrying out a multiplicity of functions – in this compilation of documents, selected to offer a very general picture of Shikasta for the use of first-year students of Canopean Colonial Rule.

JOHOR reports:

I have been sent on errands to our Colonies on many planets. Crises of all kinds are familiar to me. I have been involved in emergencies that threaten species, or carefully planned local programmes. I have known more than once what it is to accept the failure, final and irreversible, of an effort or experiment to do with creatures who have within themselves the potential of development dreamed of, planned for … and then – Finis! The end! The drum pattering out into silence …

But the ability to cut losses demands a different type of determination from the stubborn patience needed to withstand attrition, the leaking away of substance through centuries, then millennia – and with such a lowly glimmering of light at the end of it all.

Dismay has its degrees and qualities. I suggest that not all are without uses. The set of mind of a servant should be recorded.

I am a small member of the Workforce, and as such do as I must. That is not to say I do not have the right, as we all have, to say, Enough! Invisible, unwritten, uncoded rules forbid. What these rules amount to, I would say, is Love. Or so I feel, and many others, too. There are those in our Colonial Service who, we all know, hold a different view. One of my aims in setting down thoughts that perhaps fall outside the scope of the strictly necessary is to justify what is still, after all, the majority view on Canopus about Shikasta. Which is that it is worth so much of our time and trouble.

In these notes I shall be trying to make things clear. There will be others, after me, and they will study this record as I have studied, so often, the records of those who came before. It is not always possible to know, when you make a note of an event, or a state of mind, how this may strike someone perhaps ten thousand years later.

Things change. That is all we may be sure of.

Of all my embassies, that first one to Shikasta was the worst. I can say truthfully that I have scarcely thought of it between that time and this. I did not want to. To dwell on unavoidable wrong – no, it does no good.

This is a catastrophic universe, always; and subject to sudden reversals, upheavals, changes, cataclysms, with joy never anything but the song of substance under pressure forced into new forms and shapes. But poor Shikasta – no, I have not wanted to think about it more than I had to. I did not make attempts to meet those of the personnel who were being sent (oh, many thousands of them, and over and over again, for no one could accuse Canopus of neglect of that unfortunate, Shikasta, no one could feel that we have evaded responsibilities), who were sent, and returned, and who filed their reports as we all did. Shikasta was always there, it is on our agenda – the cosmic agenda. It is not a place one could choose to forget altogether, for it was often in the news. But I, for one, did not ‘keep myself in touch’, ‘informed’ – no. Once I had filed my report that was that. And when I was sent again, on my second visit, at the Time of the Destruction of the Cities, to report on the results of such a long slow atrophy, I kept my thoughts well within the limits of my task.

And so, returning again after an interval – but is it really so many thousands of years? – I am deliberately reviving memories, recreating memories, and these attempts will take their place in this record where they may be appropriate.

From: NOTES on PLANET SHIKASTA

for GUIDANCE of COLONIAL SERVANTS

Of all the planets we have colonized totally or in part, this is the richest. Specifically: with the greatest potential for variety and range and profusion of its forms of life. This has always been so, throughout the very many changes it has – the accurate word, we are afraid – suffered. Shikasta tends towards extremes in all things. For instance, it has seen phases of enormousness: gigantic lifeforms and in a wide variety. It has seen phases of the minuscule. Sometimes these epochs have overlapped. More than once the inhabitants of Shikasta have included creatures so large that one of them could consume the food and living space of hundreds of their co-inhabitants in a single meal. This example is on the scale of the visible (one might even say the dramatic), for the economy of the planet is such that every lifeform preys on another, is supported by another, and in turn is preyed upon, down to the most minute, the subatomic level. This is not always evident to the creatures themselves, who tend to become obsessed with what they consume, and to forget what in turn consumes them.

Over and over again, a shock or a strain in the peculiarly precarious balance of this planet has called forth an accident, and Shikasta has been virtually denuded of life. Again and again it has been jostling full with genera, and diseased because of it.

This planet is above all one of contrasts and contradictions, because of its in-built stresses. Tension is its essential nature. This is its strength. This is its weakness.

Envoys are requested to remember at all times that they cannot find on Shikasta what they will have become familiar with in other parts of our dominion and which therefore they will have become disposed to expect: very long periods of stasis, epochs of almost unchanging harmonious balance.

For instance. They may care to stand in front of the Model of Shikasta, Scale 3 – scaled, that is, to roughly present sizes. (Dominant species half of Canonean size.) This sphere, which you will see as they see it on their mapping and cartographic devices, has the diameter of their average predominant-species size. You will observe over the larger part of the sphere a smear of liquid. It is on this film of liquid that the profusion of life depends. (This planet knows nothing of the little scum of life on its surface: the planet has other ideas of itself, as we know; but that is not our concern here.) The point of the exercise is this: to understand that the proliferation of organic possibilities, the harvest of potentiality which is Shikasta, depends, from one point of view, on a scrape of liquid that could be drunk in a moment by a rogue star, or shaken off like puddle-mud from a child’s ball during a game if a comet came in from elsewhere. Which event would be, after all, not without its precedents!

For instance. Adjust yourself to the various levels of being which lie in concentric shells around the planet, six of them in all, and none requiring much effort from you, since you will be entering and leaving them so quickly – none save the last Shell, or Circle, or Zone, Zone Six, which you must study in detail, since you will have to remain there for as long as it takes you to complete the various tasks you have been given: those which can be undertaken only through Zone Six. This is a hard place, full of dangers, but these can easily be dealt with, as is shown by the fact that not once have we ever lost one of our by now many hundreds of emissaries there, not even the most junior and inexperienced. Zone Six can present to the unprepared every sort of check, delay, and exhaustion. This is because the nature of this place is a strong emotion – ‘nostalgia’ is their word for it – which means a longing for what has never been, or at least not in the form and shape imagined. Chimeras, ghosts, phantoms, the half-created and the unfulfilled throng here, but if you are on your guard and vigilant, there will be nothing you cannot deal with.

For instance. It is suggested that you take time to acquaint yourself with the different focuses available for viewing the creatures of Shikasta. You will find every dimension possible to Shikasta in rooms 1-100 in Section 31, from the electron all the way up to the Dominant Animal. The fascinations of these different perspectives are real dangers. On the scale of the electron Shikasta appears as empty space where tinily vibrate shaped mists – the faintest possible smears of substance, the minutest impulses separated by vast spaces. (The largest building on Shikasta would collapse if the spaces that hold its electrons apart were withdrawn, into a piece of substance the size of a Shikastan fingernail.) Shikastan experience in the range of sound is not something to submit yourself to, if you have not become practised. Shikasta in colour is an assault you will not survive without preparation.

In short, none of the planets familiar to us is on as strong and as crude levels of vibration as is Shikasta, and too long a submission of one’s being to any of these may pervert and suborn judgment.

JOHOR reports:

When I was asked to undertake this mission, my third, it was not expected that I would spend much time in Zone Six, but that I would move through it fast, perhaps stopping only as long as I would need for a task or two. But it was not known then that Taufiq had been captured and that others would have to do his work, myself in particular. And do it quickly, for there would not be time for me to incarnate and grow to adulthood before attending to the various urgencies that had developed because of Taufiq’s misfortune. Our personnel on Shikasta are stretched to capacity as it is, and there is no one equipped to replace Taufiq. It is not always realized that we are not interchangeable. Our experiences, some chosen, some involuntary, mature us differently. We may have all begun on one of the planets, and some of us even on Shikasta in the same way, and with not much more to choose between us than between puppies of the same litter, but after even some hundreds of years, let alone thousands, we have been fused, baked out, crystallized, into forms as different as snowflakes are to each other. When one of us is chosen to ‘go down’ to Shikasta or any other planet, it is only after deliberation: Johor is fitted for this or that task, Nasar for that one, and Taufiq for a specific, difficult long-term job that it seemed he and only he could do – and in parentheses and without emphasis I confess here that there is a weight of self-doubt on me. Taufiq and I have more than once been considered as very alike: not equivalents, never that, but we have often headed a short list, we have been friends for … But how many times, and in how many planets have we worked together! And if so alike, brothers, life-and-death partners, friends on that level where there is nothing that may not be said, and no aspect of each other for which both may not take on absolute responsibility; if we are so close, and he is lost to us, temporarily of course, but nevertheless lost and part of the enemy forces, then – what may I not expect for myself? I record here that as I prepare for this trip, one of whose main tasks is to take over Taufiq’s undone work, that I spend many units of energy reinforcing my own purpose: No, no, I shall not (I tell myself), I shall not go the way of Taufiq, my brother. And again: I shall withstand what I know I must … and this is why I reacted badly to the news that I must spend so much time in Zone Six. I know well from last time that it is a place that weakens, undermines, fills one’s mind with dreams, softness, hungers that one had hoped – one always does hope! – had been left behind forever. But it is our lot, our task, over and over again to submit ourselves to hazards and dangers and temptations. There is no other way. But I do not want to be in Zone Six! I was there twice before, once as a junior member of the Task Force of the First Time, then as Emissary in the Penultimate Time. Of course it will have changed, as Shikasta has.

I passed through Zones One to Five with all my inputs held to a minimum. I have visited them at various times, and they are lively and for the most part agreeable places, since their inhabitants are those who have worked their way out of and well past the Shikastan drag and pull, and are out of the reach of the miasmas of Zone Six. But they are not my concern now; and traversing them I experienced no more than rapid flickers of forms, sensations, changes from heat to cold, exhilaration. Soon I knew I was close to the environs of Zone Six by what I felt, and without being told I could have said, Ah, yes, Shikasta, there you are again – and with an inward sigh, a summoning of forces.

A twilight of grief, mists of hungry longing, a sucking drag of all the emotions – and I had to force each step, and it was as if my ankles were being held by hands I could not see, as if I walked weighted by beings I could not see. Out of the mists I came at last and there, where last time I was here I had seen grasslands, streams, grazing beasts, now was only a vast dry plain. Two flat black stones marked the Eastern Gate, and assembled there were throngs of poor souls yearning out and away from Shikasta, which lay behind them on the other side of the dusty plains of Zone Six. Feeling me there, for they could not then see me, they came jostling forward like blind people, their faces turning and searching, and they groaned, a deep yearning groan, and as I still did not show myself, they began a keening chant, or hymn, which I remembered hearing in Zone Six all those thousands of years before.

Save me, God,

Save me, Lord,

I love you,

You love me.

Eye of God,

Watching me,

Pay my fee,

Set me free …

Meanwhile, my eyes were at work on those faces! How many of them were familiar to me, unchanged except for the ravages of grief, how many of them I had known, even in the First Time, when they were handsome, wholesome, sturdy animals, all self-reliance and competence. Among them I saw my old friend Ben, descendant of David and his daughter Sais, and he sensed me so strongly that he was standing close against me, tears running down his face, his hands held out as if waiting for mine. I manifested myself in the shape he had seen me last, and put my hands in his, and he flung himself into my arms and stood weeping. ‘At last, at last,’ he wept, ‘have you come for me now? May I come now?’ – and all the others pressed in about us, clutching and holding, and I nearly lost myself into the gulf of their longing. I stood there feeling myself sway, feeling my substance dragged out of me, and I stepped back from them, making them release me, and Ben, too, took away his hands, but stood close, moaning, ‘It’s been so long, so long …’

‘Tell me why you are still here?’ I insisted, and they became silent while Ben spoke. But it was no different from what he had told me before, and as he finished and the others stood crying out their stories one after another, I knew I was caught and bound by the necessities of Zone Six, and my whole being was fermenting with impatience and even fear, for all my work was ahead of me, my work was calling me – and I could not get myself free. What they told me was always the same, had always been the same – and I wondered if they remembered how I had stood here, they had stood there, so long ago, saying the same things … they had made themselves leave this gate, and they had turned themselves around and crossed the plain, and had entered Shikasta – some of them recently, some of them not for centuries or millennia – and all had succumbed to Shikasta, had suffered some failure of purpose and will, and had been expelled back to this place, clustering around the Eastern Gate. They had tried again, some of them, had succumbed again, again found themselves here – on and on, for some, while others had given up all hope of ever being strong enough to enter Shikasta and win its prize, which was, by enduring it, to be free of it forever; and hung and drifted, thin miserable ghosts, yearning and hungering for ‘Them’ who would come for them, would lift them out and away from this terrible place as a mother cat takes its kittens to safety. The idea of rescue, of succour, was evidenced here always, at this gate, as strongly as I have known it anywhere, and the clutch and cling of it was maddening me.