скачать книгу бесплатно

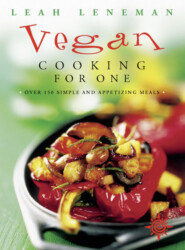

Vegan Cooking for One: Over 150 simple and appetizing meals

Leah Leneman

A new edition of the Single Vegan, which has sold over 60,000 copies, which contains 30% new recipesOften vegans, although they may be part of a large family, have to cook separate meals – this cookbook offers over 200 diverse and seasonal recipes to tempt the tastebuds.The book is split into weeks – and has essential shopping lists for all the ingredients you will need for that week and then delicious recipes to follow. There is also a Spring and Summer collection and an Autumn and Winter collection so that the availability and freshness of ingredients is assured.The recipes are both savoury and sweet, main meals and light snacks and have influences and flavours from around the world.

Vegan Cooking for One

Leah Leneman

Contents

Cover (#u828e1002-7e60-5097-9e4c-b886dbaf9d05)

Title Page (#u4d7a62c9-d92f-5df3-a64a-9f307c9c31b3)

Introduction

Introduction to the New Edition

SPRING/SUMMER RECIPES

Week 1

Week 2

Week 3

Week 4

Week 5

Week 6

Week 7

Week 8

Week 9

AUTUMN/WINTER RECIPES

Week 1

Week 2

Week 3

Week 4

Week 5

Week 6

Week 7

Week 8

Week 9

Index

By the Same Author:

Copyright

About the Publisher (#u72b1ee97-e141-5fa0-8888-22f14e4d8784)

Introduction (#udec9f122-bda3-5001-9dd8-a222cc51d2ab)

Most cookery books, vegan or otherwise, are aimed at a family of four, and dividing ingredients to make them suitable for one is often not feasible. Of course, the same dish could be eaten four nights running, but who wants to do that? Or you could freeze the remainder, but only certain types of dishes are suitable for freezing, and it still means eating leftovers. Also, many of the recipes found in ordinary cookery books involve a degree of time and effort which may be appropriate for the preparation of a meal for a family, a partner or friends, but does not seem worth the bother when cooking just for oneself.

It is not just the amount of time needed to cook a meal that counts either; the planning involved is often the most off-putting thing. Yet to stick to the same tried and true recipes day after day is very boring indeed – no wonder so many companies are now producing convenience meals for one person! Some of them aren’t bad at all, but they rarely match up to a home-cooked meal, and they are much more expensive.

This book is designed to overcome those obstacles to cooking for one. Each week begins with a Sunday lunch. Dinner on Sunday night is slightly more time-consuming than on other nights of the week, as this is likely to be the one day of the week when some extra time can be afforded. And for this meal a dessert recipe is also provided. From Monday to Friday the assumption is that lunch will be had out. The recipes for evening meals are all quick and easy to prepare, while at the same time providing lots of variety. For Saturday a lunch recipe is given, but the likelihood is that one night a week a break from cooking will be desired, and a meal had at a restaurant or with friends. By the end of any week all perishable ingredients will have been used up, and, to make the planning as simple as possible, a shopping list precedes each week’s menus.

The book does not, however, have to be utilized in the way described above; it can be used in the same way as any other cookery book, since each recipe stands on its own. Nor does it have to be used for single people only; ingredients are far more easily doubled, or even quadrupled, than halved or quartered. And although the recipes are all vegan – for even vegans not living alone may have to prepare separate meals for themselves – the menus aim to be interesting and varied enough to satisfy vegans, lacto-vegetarians and omnivores.

Breakfast

Given the importance of starting the day with something nourishing, one can’t really not mention breakfast, although no recipes are provided. Vegans have plenty of choice these days with dairy-free mueslis and the like (however, some cereals are not suitable because they are fortified with an animal-derived vitamin D). Porridge is a nice starter for a cold winter’s morning; or for a savoury hot breakfast, scrambled tofu, or thinly sliced and fried tofu, fits the bill nicely. Breakfast is one meal that causes no problems to single vegans.

Lunch

As indicated in the introduction above, the assumption is that the majority of people using this book will not be concerned with preparing a daily lunch. Every vegetarian restaurant now caters for vegans, and even non-vegetarian restaurants often have vegan salads and/or baked potatoes, etc. Eating lunch out in many parts of the country is no longer a problem for a vegan.

If daily restaurant lunches are not easily affordable then it is easy enough to bring a packed lunch in to work. There are an increasing number of vegan pâtés and spreads for sandwiches, as well as vegan biscuits. A number of the Saturday and Sunday lunch dishes in this book – such as spreads, salads and the like – could be taken to work for midday lunches as well.

For those who do not go out to work but lunch at home, the weekend lunch recipes could be used. A healthy alternative is simply a daily mixed salad, with differing ingredients and accompaniments for variety. There are also many more packet soups and convenience foods like tofu burgers which are vegan these days.

There are some people who prefer to eat a large midday meal and only a light supper in the evening; the daily recipes could of course be used for a midday meal and the above suggestions be utilized for the evening meal.

Quantities

The most useful kitchen implement for a single person is a dieter’s scale: using one of those you can weigh as little as ¼ oz (5g), which is invaluable for small quantities.

Many cookery books insist that imperial and metric measurements should not be mixed. As far as I am concerned, anyone using this book should feel free to mix imperial, metric and even American measurements to their heart’s content. The recipes are intended to be robust enough not to require precision, which is why, in the newer recipes particularly, I have often suggested a range of quantities of a particular ingredient, to give maximum flexibility.

The weekly menus are intended to use up all ingredients that would otherwise spoil and are based on standard-sized cans. When using half a can of beans or other vegetables in one recipe, the other half should be transferred to a glass or plastic container and refrigerated until needed later in the week. In the UK tofu is usually found in 8 or 10 oz packets, and I have therefore used this amount as the basis of a week’s menus, but there are various recipes calling for frozen tofu, so if a larger quantity is purchased the remainder can be frozen.

Vegetables

Recipes in standard cookery books often call for 1 onion or 2 onions, which is a bit meaningless since one can buy onions as small as 2 oz (55g) or as large as 8 oz (225g). When I specify a ‘small onion’ I mean 2–4 oz (55–115g). It is usually quite easy to find onions of this size, but if your local shop only has large ones you can chop off this amount, wrap the remainder in clingfilm and store it in a fridge until onion is required for another recipe. Garlic cloves are also very variable in size; if the only kind available seems large enough to flavour a dish for four people then this too can be quartered with the remainder wrapped in clingfilm and stored in the fridge (though it’s a good idea to put an extra plastic bag round it to keep the fridge from reeking of garlic). When a recipe calls for a small carrot I mean 2–3 oz (55–85g); a small green pepper is about 6 oz (170g), a small courgette (zucchini) 3–4 oz (85–115g).

Certain vegetables are more awkward for one person to use, for example cauliflower. I have tried always to incorporate such vegetables into more than one recipe in a week’s menu so that you are not left with a large chunk of it in the fridge with no idea what to do with it. Celery is a particular nuisance I find because a little of it goes very nicely in some dishes but as a whole head is difficult to use up. Spring onions (scallions) are arguably in the same category except that they will keep in the fridge for some weeks.

I know that some single people prefer to keep a stock of frozen vegetables, but I can’t see the point when it is easier (and a lot cheaper) to buy half a dozen fresh Brussels sprouts than to pull out the same number of frozen ones. The only exception I make is green beans or peas when they are out of season.

Pulses

Many of the recipes in this book call for canned beans. The reason is simply that unless you have a pressure cooker, cooking dried beans takes an awfully long time, which may be acceptable if you are cooking for a family but not for a single person. Unlike vegetables, which lose vitamins (not to mention flavour) when canned, protein is not lost in the canning process, so canned beans are as nutritious as freshly cooked ones. Admittedly they can be high in salt content, and some British brands add sugar as well, but it is easy enough to rinse the beans off before using them. There is no doubt, however, that canned beans work out a lot more expensive than dried ones, so if money is more important than time then by all means use home-cooked beans instead of canned ones: a small can or half a large one is equivalent to 2 oz (55g) dried beans, and an ordinary can to about 4 oz (115g).

Butter (lima) beans and red kidney beans are available in small cans, which obviates the need to use the other half of a can later in the week. All other beans are available only in larger cans so I have used them in two recipes in the relevant week. The beans not used in the first recipe should not be left in the can but transferred to a jar and refrigerated until required.

Certain pulses – e.g., lentils, aduki beans, split peas, and black-eyed peas – are not readily available in cans and are quite quick to cook so in those cases the dried varieties are called for.

Salads

There are basically two types of salad. (Well, three if you count the typical British salad of limp lettuce leaves, a slice of tomato and one of cucumber, topped with something sliced, with vinegary salad cream over it, but anyone reading this book is unlikely to think of such a thing when talking of salads.) The first kind of real salad is a meal in itself. Such salads feature as recipes for some weekend lunches.

The second kind is a side salad, i.e., it accompanies a dish in the same way as cooked vegetables. Many of the recipes in this book would be nice accompanied by a salad even when this is not specified. It is easy enough to make a salad for one person. Some lettuce or cress, a small grated carrot, a few sliced button mushrooms – that alone makes a very palatable salad even if there is nothing else to add to it, and if there is celery, a few spring onions (scallions), green pepper or other leftovers in the fridge, so much the better. A few chopped black olives really zing up a salad. The easiest dressing for this type of salad is a little oil – especially virgin olive oil – mixed with a little cider vinegar or lemon juice, perhaps with a pinch of mustard, and any additional seasoning desired. It is useful to have a ready-made vinaigrette dressing handy, but unfortunately most supermarket ones are made with malt vinegar which is anything but nutritious (or even nice). Fortunately, more wholefood shops are beginning to stock good ones.

Herbs and Spices

It has become easier to obtain fresh herbs of late, and some people grow their own. Obviously fresh herbs have a wonderful flavour, and anyone who has access to them will certainly want to use them, but the majority will find it much easier to keep a variety of dried herbs in stock. When herbs are called for in recipes it is dried herbs that are meant.

As far as spices are concerned, although there is nothing intrinsically wrong with the mixture of spices which go to make up ‘curry powder’, far more interesting variations of flavour can be obtained by using the spices themselves. For the best flavour, coriander and cumin seeds are much better bought whole and ground in a small pestle and mortar when required. I realize such a suggestion may seem surprising in a book which is aimed at simple and quick recipes, but the average time required to grind a teaspoonful of spice cannot be more than about five seconds, and it is especially beneficial when cooking for one simply because these spices are likely to be stored for a long time, since only a little is required for any one dish, and if bought already powdered then much of the flavour will gradually be lost.

Rice and Pasta

If used straight from the packet, brown rice generally takes about 45 minutes to cook, which makes it less than ideal for a really quick meal. However, if it is covered with boiling water in the morning and left to soak all day then it will only take about 20–25 minutes. (The method is to drain the soaking water, cover the rice with water about a ¼-inch (5mm) over the top and a little salt, bring to the boil, lower heat, cover pan and simmer until all the water is absorbed.) This is all very well for well-organized people but rather annoying if you arrive home in the evening to realize you have forgotten the soaking step. There are now several brands of brown rice available in supermarkets which require no soaking and take only 25 minutes or so to cook. The method with these types of rice is different: the rice is covered with lots of boiling water and simmered uncovered before being drained and more hot water poured over it. As the water is not all absorbed, this type of rice is not suitable for pilaus and similar dishes which require the flavouring to be incorporated into the rice. These supermarket packets also work out rather more expensive than rice bought at a wholefood shop. The best compromise may be to use the latter normally but keep the supermarket kind in stock for emergencies or when the soaking has been forgotten. I find about 3 oz (85g) wholefood shop brown rice or 2½ oz (70g) supermarket brown rice to be right for one serving.

Wholemeal (whole wheat) pasta is available now in a variety of shapes and sizes. Not all of the packets provide information on cooking time. Twelve to fifteen minutes seems to be about the average time required for most types of wholemeal (whole wheat) pasta to cook.

Most Chinese noodles are egg noodles, but Chinese shops (and some supermarkets) sell a variety of eggless noodles, some made from wheat flour and some from rice flour. Wholemeal (whole wheat) Chinese-style noodles are available at some health food stores. Most need little or no cooking, making them an ideal food for those in a hurry.

Dessert

Dessert is not a necessary part of anyone’s diet, and many people are perfectly happy to end a meal with a savoury taste. Unfortunately, there are many of us brought up in such a way that a meal simply is not complete unless it ends with a sweet. For those of us in that situation all that can be done is to try and make the sweet course a healthy addition to the diet.

Fresh fruit is the most commonly suggested healthy dessert, but for die-hard sweet-toothed types, a fresh apple, pear or banana, which may be very welcome in the morning or between meals, does not constitute a real dessert. That is not to say there aren’t some fresh fruits which do. In the summer months fresh strawberries, raspberries, and similar soft fruit – particularly if served with cashew or coconut cream – certainly does, also sweet melons and the like. In the winter tropical fruits like fresh pineapple or mango are definitely reserved for dessert. Another winter fruit which can be classified as a dessert is the persimmon (also called Sharon fruit). For those who have not tried this fruit, it should be eaten when it is so soft it feels almost rotten. The skin is peeled off and the inside is unbelievably sweet.

Canned fruit is not the same, of course, but there are an increasing number of varieties canned in juice rather than sugar syrup: served with cashew cream or custard made from soya milk, they can serve as a pleasant dessert as well.

Nowadays there are an increasing number of vegan sweets available, both in the UK and USA, including ready-made puddings and dairy-free ice creams. Naturally a convenience-type dessert can never be the same as a home-made one, which is why I have included sweet recipes for one in Sunday meals, when there may be extra leisure time to make them.

Staples

A shopping list precedes each week’s menus, but it is assumed that certain foods will be kept permanently in the larder, and therefore those foods do not appear on weekly shopping lists. The items considered staples are the following:

HERBS

Sage

Thyme

Marjoram

Basil (sweet basil)

Oregano

Bay leaves

Rosemary

Mint

SPICES

Nutmeg

Cinnamon

Cloves

Ginger

Turmeric

Cumin

Coriander

MISCELLANEOUS

Wholemeal (whole wheat) bread

Sea salt and black pepper

Garlic salt

Baking powder

Raw cane sugar

Wholemeal (whole wheat) flour

Yeast extract

Nutritional yeast flakes or powder