Полная версия:

Harry and Hope

Copyright

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2015

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Copyright © Sarah Lean 2015

Illustrations © Gary Blythe 2015

Cover photographs © Mark harris (dog), Cavan images / Getty images (boy), Shutterstock (all other images)

Sarah Lean asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of the work.

Gary Blythe asserts the moral right to be identified as the illustrator of the work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007512263

Ebook Edition © 2015 ISBN: 9780007512256

Version: 2015-02-05

Praise for Sarah Lean

“Sarah Lean weaves magic and emotion into beautiful stories.”

Cathy Cassidy

“Touching, reflective and lyrical.”

The Sunday Times

“… beautifully written and moving. A talent to watch.”

The Bookseller

“Sarah Lean’s graceful, miraculous writing will have you weeping one moment and rejoicing the next.”

Katherine Applegate, author of The One and Only Ivan

For my little sister

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise for Sarah Lean

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Sarah Lean

About the Publisher

It must have snowed on the mountain in the night.

“Have you seen it yet, Frank?” I shouted downstairs.

“You mean did I hear?”

“I know, funny, isn’t it? The snow’s so quiet but it’s making all the animals noisy.”

We didn’t normally see snow on Canigou in May, and it made the village dogs bark in that crazy way dogs do when something is out of place. Harry, Frank’s donkey, was down in his shed, chin up on the half open door, calling like a creaky violin.

Frank came up to the roof terrace where I’d been sleeping in the hammock. He leaned over the red tiles next to me and we looked at Canigou, sparkling at the top like a jewellery shop.

And it’s the kind of thing that is hard to describe, when snow is what you can see while the sun is warming your skin. How did it feel? To see one thing and feel the complete opposite? I only knew that other things didn’t seem to fit together properly at the moment either; that my mother and Frank seemed as far apart as the snow and the sun.

“Frank, at school Madame was telling us that the things we do affect the environment, you know, like leaving lights on, things like that,” I said. “Well, I left the lights on in the girls’ loo.”

Frank smiled. Frank was my mother’s boyfriend, but that won’t tell you what he meant to me at all. He’d lived in our guesthouse next door for three years and he wouldn’t ever say the things to me that Madame had said when I forgot to turn the lights off. In fact, what he did was leave a soft friendly silence, so I knew I could ask what I wanted to ask, because I wasn’t sure about the whole environment thing.

“Did I make it snow on Canigou?”

“Leave the light on and see if it snows again,” he whispered, grinning.

He made the world seem real simple, like a little light switch right under my fingertips. But there were other complicated things.

“Remember when the cherry blossom fell a few weeks ago?” I said.

He nodded.

“How many people do you think have seen pink snow?”

“Only people who see the world like you.”

“And you.”

I looked out from all four corners of the terrace.

South was the meadow, and then the Massimos’ vineyards that belonged to my best friend Peter’s family – lines and lines of vines curving over the steep mountainside, making long lazy shadows across the red soil paths. I thought of the vines with their new green leaves twirling along the gnarly arms, reaching out to curl around each other, like they needed to know they weren’t alone; that they’d be strong enough together to grow their grapes.

North were the gigantic plane trees with big roots and trunks that cracked the roads and pavements around the village.

East was the village, the roofs of the houses stacked on the mountainside like giant orangey coloured books left open and abandoned halfway through a story.

West were the cherry fields, and Canigou, the highest peak that we could see in the French Pyrenees. It soared over the village and the vineyards, high above us.

I touched the things I kept in the curve of the roof tiles, the wooden things Frank had carved for me. I whispered their names and picked them up, familiar, warm and softly smooth in my hands: humming bird, the letter H, mermaid, donkey, cherries, and the latest one – the olive tree knot made into a walking-stick handle that Frank said I might need to lean on to go around the vineyards with Peter when we’re ninety-nine. Always in that order. The order that Frank made them.

“What you thinking about, Frank?”

“The world,” he said quietly. “And cherry blossom.”

When you’re twelve, it takes a long time for the different sounds and words you’ve heard and the things you’ve seen to end up some place deep inside of you where you can make sense of them. It was that morning when I worked out what my feelings had been trying to tell me; when I saw Frank looking at our mountain like he was remembering something he missed; when I saw the passport sticking out of his pocket.

It felt like even the crazy dogs had known before me, as if even the mountain had been listening and watching and trying to tell me.

Frank looked over.

“Spill,” he said, which is what he always said when he knew there were words swirling inside me that I couldn’t seem to get out.

“Why did you travel all around the world, Frank? I mean, you went to loads of different countries for twenty years before you came here, and that’s, like, a really, really long time to be travelling.”

“Something in me,” he said.

“But you don’t need to go travelling again, do you?”

For three whole years my mother and I had been more than the rest of the world to him.

He looked down at his pocket, knew what I had seen. Tilted his leather hat forward to shade his eyes.

“What I mean is…” I didn’t know exactly how to explain. A boyfriend was somebody for my mother. For me, it used to be a person who picked me up and swirled me around and bought me soft toys which, after a while, I binned because the person who bought them always left. But that wasn’t what Frank did. There wasn’t a word for what Frank was to me. I mean, how can you explain something when there isn’t even a word for it? I just wanted to ask: if he was thinking about leaving, what about me? How would we still fit together?

“What I mean is…” I tried again. “Say you like cherries, which I do, and then you eat them with almonds, which I also like a lot… you get something else, right? Something that makes the cherries more cherry-ish and the almonds more kind of almond-y.”

“Like tomatoes and basil?” Frank said. His favourite.

Down below us, Harry kicked at his door. And Harry… well, you couldn’t have Frank without Harry. They were definitely as good together as yoghurt and honey.

“Yes, like that,” I said. “But also you and Harry, Mum and you, you know, there’s these kinds of pairs of us.”

“You and Peter?”

“Yeah, us too. These pairs you made of us.” I picked the little wooden donkey up, turned it in my hands. “I feel kind of smoother, and sort of… more, when we’re together.” That’s what I felt about me and Frank. “I’m kind of more me when you’re around.”

“Hope Malone,” he said. “You have your own things that are just you.”

I said, “But I’d be just half of me without you.”

Frank pushed his passport deeper into his pocket.

“Are you planning on going somewhere, Frank?”

“We’ll talk later,” he said as Harry’s hoof clattered against his shed again. “I’d better let that donkey out before he kicks the door down.”

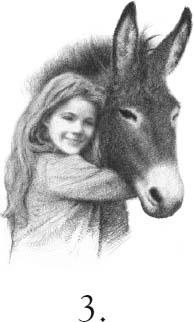

Anybody would love Harry straight away. As soon as you put your hand out to touch him and he greeted you in his nuzzly donkey kind of way, he made you feel so nice. He was only little, about as high as my waist, with stick spindly legs, but round where there was much more of him in the middle. I always thought he was a bit shy, the way his eyelashes curled up and the fact that he never looked you in the eye. He seemed to hear everything Frank said, though, like the words poured down his tall ears and into his whole skin and bones and barrelled belly.

“Going somewhere?” Frank said, as Harry barged out of his shed, quivering with happiness just because Frank spoke to him. Harry trotted straight over to the trailer hitched to the back of Frank’s dusty jeep.

“Where are you going?” I asked.

“Same as always,” Frank said.

I mean, I knew where they were going because they always did the same thing every day. Frank would have to drive Harry along the lane and back again before Harry would go down to the meadow. It was an old habit of Harry’s from their travelling days years ago. If they didn’t go for a spin with the jeep and trailer, Harry wouldn’t go down to the meadow, no matter how big the carrot you held in front of his nose was. I completely got it, why Harry had to have things as they always were. Frank had rescued Harry and brought him over from India. Harry was safe, getting in the trailer every day and not going back to how his awful life was.

Same as always. But what about Frank’s passport?

I watched them go before running back up to the roof to get dressed.

Marianne was up there with her camera, taking photographs of Canigou.

Everyone called my mother Marianne, even me most of the time. She was an artist. Her bedroom and studio, where she’d normally be, were on the first floor next to each other. She usually stayed there most of the day and didn’t come out into the world if she didn’t want to. We weren’t allowed to go and disturb her either.

“The cherry blossom’s all gone,” she said.

“It’s been gone ages.”

“Oh, I hadn’t noticed.”

I coughed. “Excuse me, I want to get dressed.”

“I’m not looking,” she said, turning the camera towards Canigou. “Why are you sleeping up here anyway?”

As soon as it was warm enough I had wanted to sleep outside, so that if I woke up, I would see the dark shape of the mountain between the stars, even on the blackest night. I didn’t say that though, because I couldn’t talk to her about things like that. I couldn’t have just burst into her space and told her that the blossom was falling and it was so beautiful I might explode. There’s only that one moment when you feel like that and then it’s gone, and these things I wanted to say didn’t ever seem to fit with Marianne at the right time. So I’d gone and told Frank and he’d stood and watched with me and there was nothing left to say anyway, because Frank and I were the same, all filled up with that blustery breeze making pink snow of the blossom.

“It’s too hot in my bedroom,” I said, rummaging under the blankets drooping over the hammock and on to the floor. “I can’t find my shoes.”

“Where are the new ones I bought you?”

I shrugged.

“In your other bedroom, probably still in the box,” said Marianne.

I took my clothes downstairs and got changed. I grabbed my new shoes from the box in my room and a croissant from the kitchen and went outside with the croissant in my mouth to wait for Harry and Frank.

When they got back, Harry trotted out of the trailer, looked around, and Frank frowned and said to him, “You never give up, do you, Harry?”

“He’s a creature of habit,” I said. The croissant muffled the words in my mouth and flakes dropped all over me so I jumped up and down to shake them off. “That’s what you always say. Like all of us.”

“Seen Marianne this morning?” Frank asked.

I nodded. “I expect she’s in her studio now.”

I shoved my feet in my shoes without pushing my heels in and scuffed after Frank and Harry. Slowly Harry headed to the meadow, as always, in that kind of, oh yeah, I nearly forgot, there’s a lovely meadow for me here kind of way. I hoped Frank still thought that too. That this was the place where they both fitted perfectly.

Frank pointed towards something lying in the grass. I’d left my other shoes in the meadow yesterday. Harry had chewed on them. Frank had made me lots of rules since he lived here. Marianne said artists don’t like rules. But I’d got used to Frank’s because he was never mean and bossy, and that helped me remember them, almost all the time.

“Oh,” I said, picking the shoes up, disappointed I’d done something stupid. The canvas was shredded, the laces unravelled. “I know, I know, I’m not supposed to leave anything in the meadow. Sorry, it was just this one time I forgot because Peter and I were hiding things in the grass and trying to find them with bare feet and our eyes closed. I won’t do it again.”

“Hope—”

“I don’t mind, honest. I’ve got these,” I lifted my foot up to show Frank the new ones and hooked the back with a finger to get my heel in. “The others were too small anyway.”

“What might happen to Harry if he ate something he shouldn’t?”

“Oh.” But Frank didn’t make me feel stupid, just kind of like I’d try harder next time. “Sorry. Sorry, Harry.”

Frank shoved his hands in his pockets and I followed his eyes to the snow on Canigou. I hadn’t finished what I was saying earlier.

“Do you think it works the other way around?” I said. “I mean, because of the environment, because Canigou is different today, can it change us?”

Frank had stayed put for three years now. Had he changed enough to stay for good?

I looked across and Frank didn’t say anything because we had this other kind of quiet world where we totally got each other. He taught me you didn’t always have to have an answer straight away.

“Where you off to today?” he said instead.

“I was going to the waterfall,” I said, cramming the last of the croissant into my mouth. “Peter and I were going to check on the swing to see if it needs fixing, ready for summer holidays. But actually I think I’ll stay here today. With you and Harry.”

“Peter’s last day, isn’t it?” Peter went to boarding school in England and was only home for the break.

“Yes, but—”

“Go on,” Frank said. “I’ll be here when you get back.”

I still didn’t go.

“I’ll find some wood.” He smiled.

I knew that meant we’d sit outside by the fire-pit this evening, talking in the honey-coloured light with the mountain looking over us. About all the things I couldn’t say to Marianne.

All I had to do was find a way to remind Frank of all the good things about being here, all the good things that made pairs of us, and then he wouldn’t even think about going anywhere else.

I nodded.

“See you by the fire later,” he said.

Before I met Peter, I’d only ever heard that he was the rich kid from the vineyards and didn’t play with anyone else in the village, which was enough information for me to think we’d never be friends. The day that Frank and Harry arrived three years ago, Peter turned up too. He sat on the meadow fence and watched Frank introducing me to Harry, and then all Peter did was come over and ask Frank if he could stroke Harry too.

Frank said what he’d already just said to me when I’d asked the exact same question. “You need to give Harry a bit of time to get used to you first.” I looked at Peter’s big brown eyes, and when Frank said, “He doesn’t know yet if you’re going to be kind to him,” I murmured along with Frank what I knew he was going to say next: “even though I do.”

I had one more day with Peter before I lost him to boarding school and would have to wait ages for him to be on holiday again. I ran across the meadow and Harry trotted alongside me until I climbed through the hole in the fence, into the vineyard, and raced on to Peter’s grandparents’ house, turning back to see Harry with his chin up on the top rung, his ears pointing high, watching me go.

“See you later, Harry!”

That donkey would always think he was coming with you.

Peter was dressed smart, as always. Even if we were going crawling through vineyards or driving Monsieur Vilaro’s rusty old tractor he looked kind of pressed and tidy and new. I liked my clothes, they made me feel comfortably like me, but I always got the feeling when I was next to Peter that actually my clothes were scruffy, not casual.

Peter was packing a towel into a bag.

“Are you going swimming? We never swim until July. The water’s too cold,” I said. “And anyway I haven’t brought a towel.”

“I’m going to swim; you can watch. If you change your mind then you can share my towel.”

“I thought we were going to make the swing ready for when you come back?”

“We are,” he said, winking. “Ciao, Nanu,” (which means Bye, Nanny) he called back as I followed him outside. Peter’s grandparents were Italian and although they’d lived here in France for over fifty years, they still didn’t speak much French or English, unlike Peter.

Outside, Peter said, all kind of secretive, “Today’s the day.”

“The day for what?”

“Jumping off the waterfall.”

“You say that every year.”

“I mean it this time.”

“What, from the top? You’ve always said it’s too high.”

“But I’m taller than I was before.”

I looked at the top of his head. With my hand, I measured his height against me, pressing his thick wavy hair down in case that was what was making him look taller, but he’d had his hair cut short ready for school, so it wasn’t that.

“For the first time ever, you are actually just a teeny, weeny bit taller than me,” I said, which made him grin. “But I’m not doing it.”

As we walked we discussed the good and bad things about jumping off waterfalls, asking each other if we’d heard of Angel Falls and Victoria Falls, Peter agreeing in the end that he would swim to the bottom first to check if there were any rocks under the water.

There was a shortcut across the Vilaros’ field, although we weren’t supposed to use it, and when we got near the gate the Vilaros’ guard dog, Bruno, blocked our way. Bruno usually just paced around the field, guarding against… well, I had no idea what, but this time he barked and barked at us in that way that made you not want to go any further.

Bruno’s chops dripped drool with the effort of the big noise he was making and Peter turned and walked back down the lane (well, kind of ran actually), probably expecting me to be right behind him as usual. Bruno was a big dog, not a house dog, with battle-tatty ears and grey chops, and I’d never taken much notice of him before, except when I had to avoid him on the way to school, but there was something about him that day that I couldn’t ignore.

“All right, Bruno, we’re not going across the field,” I said.

He kept barking, to tell me he was on patrol and wouldn’t be letting us past.

“Hope, come on! We can go through the vineyards instead,” Peter called.

All the dogs in the village were crazy with something that day and although Bruno was usually barky and grumpy, he seemed more upset than usual.

“Peter, I think something’s wrong.”

“Come away. Bruno doesn’t look very happy about us being here.”

“He’s never bitten us before.”

“That doesn’t mean he won’t today.”

“Peter, wait. I can’t just leave him on his own like this.”

In my pocket were some sherbet lemons. I thought if I gave Bruno something sweet it might make him stop barking and howling like that. I threw one at him and he snatched it up and spat it out again, probably because when you think about it lemons aren’t that sweet at all. He kept barking, looking at Peter and me, then staring up at the mountain.

“Look, Peter. Bruno isn’t even barking at us. He’s barking at the snow.”

Peter peeked out from behind the hedge at the bottom of the lane, his eyes wide when he realised I wasn’t with him, madly waving me to come.

“Bruno?” I said. “Are you talking about the mountain?”

Bruno watched Peter creeping back up the lane on tiptoes, all hunched up and clinging to the hedge, whispering, “Hope! Please come!”

“Peter, you’re being silly,” I said, “Bruno isn’t going to hurt us. I think he might even be trying to talk to Canigou, and he has to bark big and loud like that so it can hear.”

Peter rolled his eyes at me, which he does a lot, and said, “Now who’s being silly? Let’s go!”

By now Peter had crept back to where I was. He grabbed my hand and then I was running with him down the lane in that way, you know, when you feel like you’re not going to stop and it makes you excited and scared at the same time, and you scream and laugh together, and it felt good so I didn’t look back at that big old barky dog.

Peter and I climbed over the vineyard fence and through the hole in the hedge, a hole we’d made for avoiding Bruno before. We ran up the long path of stony earth between the vines, turned right to go through the next vineyard, and then across the track behind the Vilaros’ field. Bruno had raced through the field up to the wall and was still barking, his paws up on the wall, and then suddenly he stopped. Everything went silent. After all that noise, it made me look up instead of where my feet had to go.