Полная версия:

The Complete Broken Empire Trilogy: Prince of Thorns, King of Thorns, Emperor of Thorns

Mark Lawrence

The Broken Empire Trilogy

Book 1: Prince of Thorns Book 2: King of Thorns Book 3: Emperor of Thorns

Copyright

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Prince of Thorns

First Published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2011

Copyright © Mark Lawrence 2011

Cover Layout Design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2011

Cover illustration © Jason Chan

King of Thorns

First Published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2012

Copyright © Mark Lawrence 2012.

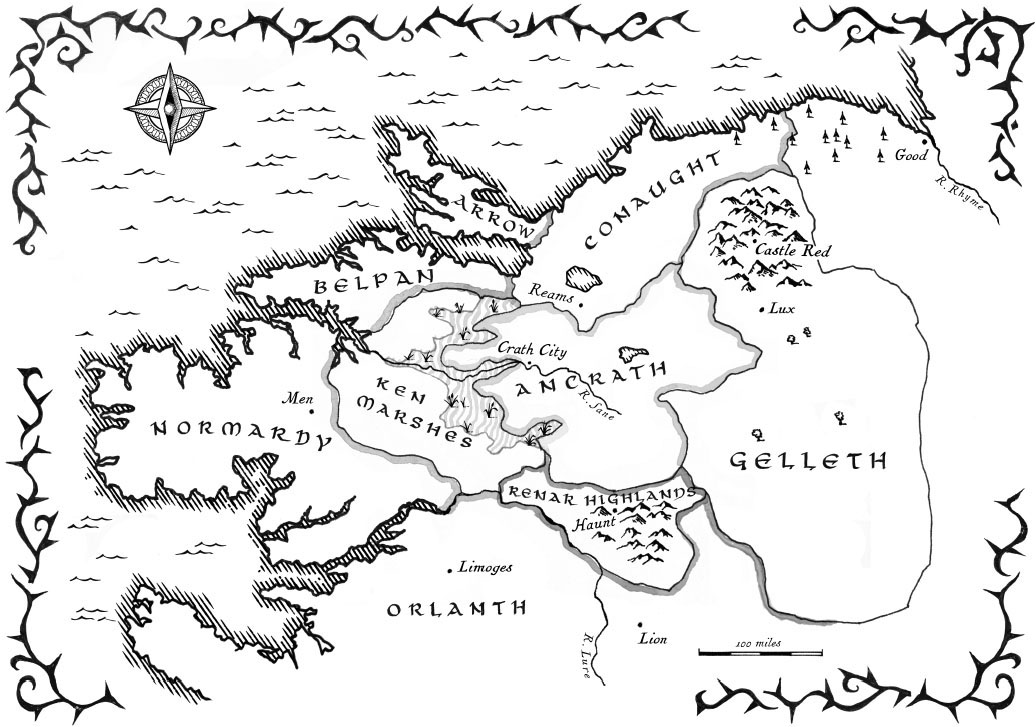

Map © Andrew Ashton

Cover Layout Design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2012

Cover illustration © Jason Chan

Emperor of Thorns

First Published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2013

Copyright © Mark Lawrence 2013

Map © Andrew Ashton

Cover Layout Design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2013

Cover illustration © Jason Chan

Mark Lawrence asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBNs:

Prince of Thorns: 9780007423293

King of Thorns: 9780007439034

Emperor of Thorns: 9780007439065

Bundle Edition (Containing Prince of Thorns, King of Thorns and Emperor of Thorns) © November 2014 ISBN: 9780008113704

Version: 2014-09-23

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Prince of Thorns

King of Thorns

Emperor of Thorns

About the Author

Also by Mark Lawrence

About the Publisher

PRINCE OF THORNS

Book One of The Broken Empire

Mark Lawrence

To Celyn, the best parts were never broken.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Map

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Acknowledgments

1

Ravens! Always the ravens. They settled on the gables of the church even before the injured became the dead. Even before Rike had finished taking fingers from hands, and rings from fingers. I leaned back against the gallows-post and nodded to the birds, a dozen of them in a black line, wise-eyed and watching.

The town-square ran red. Blood in the gutters, blood on the flagstones, blood in the fountain. The corpses posed as corpses do. Some comical, reaching for the sky with missing fingers, some peaceful, coiled about their wounds. Flies rose above the wounded as they struggled. This way and that, some blind, some sly, all betrayed by their buzzing entourage.

‘Water! Water!’ It’s always water with the dying. Strange, it’s killing that gives me a thirst.

And that was Mabberton. Two hundred dead farmers lying with their scythes and axes. You know, I warned them that we do this for a living. I said it to their leader, Bovid Tor. I gave them that chance, I always do. But no. They wanted blood and slaughter. And they got it.

War, my friends, is a thing of beauty. Those as says otherwise are losing. If I’d bothered to go over to old Bovid, propped up against the fountain with his guts in his lap, he’d probably take a contrary view. But look where disagreeing got him.

‘Shit-poor farm maggots.’ Rike discarded a handful of fingers over Bovid’s open belly. He came to me, holding out his takings, as if it was my fault. ‘Look! One gold ring. One! A whole village and one fecking gold ring. I’d like to set the bastards up and knock ’em down again. Fecking bog-farmers.’

He would too: he was an evil bastard, and greedy with it. I held his eye. ‘Settle down, Brother Rike. There’s more than one kind of gold in Mabberton.’

I gave him my warning look. His cursing stole the magic from the scene; besides, I had to be stern with him. Rike was always on the edge after a battle, wanting more. I gave him a look that told him I had more. More than he could handle. He grumbled, stowed his bloody ring, and thrust his knife back in his belt.

Makin came up then and flung an arm about each of us, clapping gauntlet to shoulder-plate. If Makin had a skill, then smoothing things over was it.

‘Brother Jorg is right, Little Rikey. There’s treasure aplenty to be found.’ He was wont to call Rike ‘Little Rikey’, on account of him being a head taller than any of us and twice as wide. Makin always told jokes. He’d tell them to those as he killed, if they gave him time. Liked to see them go out with a smile.

‘What treasure?’ Rike wanted to know, still surly.

‘When you get farmers, what else do you always get, Little Rikey?’ Makin raised his eyebrows all suggestive.

Rike lifted his visor, treating us to his ugly face. Well brutal more than ugly. I think the scars improved him. ‘Cows?’

Makin pursed his lips. I never liked his lips, too thick and fleshy, but I forgave him that, for his joking and his deathly work with that flail of his. ‘Well, you can have the cows, Little Rikey. Me, I’m going to find a farmer’s daughter or three, before the others use them all up.’

They went off then, Rike doing that laugh of his – ‘hur, hur, hur’ – as if he was trying to cough a fishbone out.

I watched them force the door to Bovid’s place opposite the church, a fine house, high roofed with wooden slates and a little flower garden in front. Bovid followed them with his eyes, but he couldn’t turn his head.

I looked at the ravens, I watched Gemt and his halfwit brother, Maical, taking heads, Maical with the cart and Gemt with the axe. A thing of beauty, I tell you. At least to look at. I’ll agree war smells bad. But, we’d torch the place soon enough and the stink would all turn to wood-smoke. Gold rings? I needed no more payment.

‘Boy!’ Bovid called out, his voice all hollow like, and weak.

I went to stand before him, leaning on my sword, tired in my arms and legs all of a sudden. ‘Best speak your piece quickly, farmer. Brother Gemt’s a-coming with his axe. Chop-chop.’

He didn’t seem too worried. It’s hard to worry a man so close to the worm-feast. Still it irked me that he held me so lightly and called me ‘boy’. ‘Do you have daughters, farmer? Hiding in the cellar maybe? Old Rike will sniff them out.’

Bovid looked up sharp at that, pained and sharp. ‘H-how old are you, boy?’

Again the ‘boy’. ‘Old enough to slit you open like a fat purse,’ I said, getting angry now. I don’t like to get angry. It makes me angry. I don’t think he caught even that. I don’t think he even knew it was me that opened him up not half an hour before.

‘Fifteen summers, no more. Couldn’t be more …’ His words came slow, from blue lips in a white face.

Out by two, I would have told him, but he’d gone past hearing. The cart creaked up behind me, and Gemt came along with his axe dripping.

‘Take his head,’ I told them. ‘Leave his fat belly for the ravens.’

Fifteen! I’d hardly be fifteen and rousting villages.

By the time fifteen came around, I’d be King!

Some people are born to rub you the wrong way. Brother Gemt was born to rub the world the wrong way.

2

Mabberton burned well. All the villages burned well that summer. Makin called it a hot bastard of a summer, too mean to give out rain, and he wasn’t wrong. Dust rose behind us when we rode in; smoke when we rode out.

‘Who’d be a farmer?’ Makin liked to ask questions.

‘Who’d be a farmer’s daughter?’ I nodded toward Rike, rolling in his saddle, almost tired enough to fall out, wearing a stupid grin and a bolt of samite cloth over his half-plate. Where he found samite in Mabberton I never did get to know.

‘Brother Rike does enjoy his simple pleasures,’ Makin said.

He did. Rike had a hunger for it. Hungry like the fire.

The flames fair ate up Mabberton. I put the torch to the thatched inn, and the fire chased us out. Just one more bloody day in the years’ long death throes of our broken empire.

Makin wiped at his sweat, smearing himself all over with soot-stripes. He had a talent for getting dirty, did Makin. ‘You weren’t above those simple pleasures yourself, Brother Jorg.’

I couldn’t argue there. ‘How old are you?’ that fat farmer had wanted to know. Old enough to pay a call on his daughters. The fat girl had a lot to say, just like her father. Screeched like a barn owl: hurt my ears with it. I liked the older one better. She was quiet enough. So quiet you’d give a twist here or there just to check she hadn’t died of fright. Though I don’t suppose either of them was quiet when the fire reached them …

Gemt rode up and spoiled my imaginings.

‘The Baron’s men will see that smoke from ten miles. You shouldn’ta burned it.’ He shook his head, his stupid mane of ginger hair bobbing this way and that.

‘Shouldn’ta,’ his idiot brother joined in, calling from the old grey. We let him ride the old grey with the cart hitched up. The grey wouldn’t leave the road. That horse was cleverer than Maical.

Gemt always wanted to point stuff out. ‘You shouldn’ta put them bodies down the well, we’ll go thirsty now.’ ‘You shouldn’ta killed that priest, we’ll have bad luck now.’ ‘If we’d gone easy on her we’d have a ransom from Baron Kennick.’ I just ached to put my knife through his throat. Right then. Just to lean out and plant it in his neck. ‘What’s that? What say you, Brother Gemt? Bubble, bubble? Shouldn’ta stabbed your bulgy old Adam’s apple?’

‘Oh no!’ I cried, all shocked like. ‘Quick, Little Rikey, go piss on Mabberton. Got to put that fire out.’

‘Baron’s men will see it,’ said Gemt, stubborn and red-faced. He went red as a beet if you crossed him. That red face just made me want to kill him even more. I didn’t, though. You got responsibilities when you’re a leader. You got a responsibility not to kill too many of your men. Or who’re you going to lead?

The column bunched up around us, the way it always did when something was up. I pulled on Gerrod’s reins and he stopped with a snicker and a stamp. I watched Gemt and waited. Waited until all thirty-eight of my brothers gathered around, and Gemt got so red you’d think his ears would bleed.

‘Where we all going, my brothers?’ I asked, and I stood in my stirrups so I could look out over their ugly faces. I asked it in my quiet voice and they all hushed to hear.

‘Where?’ I asked again. ‘Surely it isn’t just me that knows? Do I keep secrets from you, my brothers?’

Rike looked a bit confused at this, furrowing his brow. Fat Burlow came up on my right, on my left the Nuban with his teeth so white in that soot-black face. Silence.

‘Brother Gemt can tell us. He knows what should be and what is.’ I smiled, though my hand still ached with wanting my dagger in his neck. ‘Where we going, Brother Gemt?’

‘Wennith, on the Horse Coast,’ he said, all reluctant, not wanting to agree to anything.

‘Well and good. How we going to get there? Near forty of us on our fine oh-so-stolen horses?’

Gemt set his jaw. He could see where I was going.

‘How we going to get there, if we want us a slice of the pie while it’s still nice and hot?’ I asked.

‘Lich Road!’ Rike called out, all pleased that he knew the answer.

‘Lich Road,’ I repeated, still quiet and smiling. ‘What other way could we go?’ I looked at the Nuban, holding his dark eyes. I couldn’t read him, but I let him read me.

‘Ain’t no other way.’

Rike’s on a roll, I thought, he don’t know what game’s being played, but he likes his part.

‘Do the Baron’s men know where we’re going?’ I asked Fat Burlow.

‘War dogs follow the front,’ he said. Fat Burlow ain’t stupid. His jowls quiver when he speaks, but he ain’t stupid.

‘So …’ I looked around them, real slow-like. ‘So, the Baron knows where bandits such as ourselves will be going, and he knows the way we’ve got to go.’ I let that sink in. ‘And I just lit a bloody big fire that tells him and his what a bad idea it’d be to follow.’

I stuck Gemt with my knife then. I didn’t need to, but I wanted it. He danced pretty enough too, bubble bubble on his blood, and fell off his horse. His red face went pale quick enough.

‘Maical,’ I said. ‘Take his head.’

And he did.

Gemt just chose a bad moment.

Whatever broke Brother Maical left the outside untouched. He looked as solid and as tough and as sour as the rest of them. Until you asked him a question.

3

‘Two dead, two wrigglers.’ Makin wore that big grin of his.

We’d have camped by the gibbet in any case, but Makin had ridden on ahead to check the ground. I thought the news that two of the four gibbet cages held live prisoners would cheer the brothers.

‘Two,’ Rike grumbled. He’d tired himself out, and a tired Little Rikey always sees a gibbet as half empty.

‘Two!’ the Nuban hollered down the line.

I could see some of the lads exchanging coin on their bets. The Lich Road is as boring as a Sunday sermon. It runs straight and level. So straight it gets so as you’d kill for a left turn or a right turn. So level you’d cheer a slope. And on every side, marsh, midges, midges and more marsh. On the Lich Road it didn’t get any better than two caged wrigglers on a gibbet.

Strange that I didn’t think to question what business a gibbet had standing out there in the middle of nowhere. I took it as a bounty. Somebody had left their prisoners to die, dangling in cages at the roadside. A strange spot to choose, but free entertainment for my little band nonetheless. The brothers were eager, so I nudged Gerrod into a trot. A good horse, Gerrod. He shook off his weariness and clattered along. There’s no road like the Lich Road for clattering along.

‘Wrigglers!’ Rike gave a shout and they were all racing to catch up.

I let Gerrod have his head. He wouldn’t let any horse get past him. Not on this road. Not with every yard of it paved, every flagstone fitting with the next so close a blade of grass couldn’t hope for the light. Not a stone turned, not a stone worn. Built on a bog, mind you!

I beat them to the wrigglers, of course. None of them could touch Gerrod. Certainly not with me on his back and them all half as heavy again. At the gibbet I turned to look back at them, strung out along the road. I yelled out, wild with the joy of it, loud enough to wake the head-cart. Gemt would be in there, bouncing around at the back.

Makin reached me first, even though he’d rode the distance twice before.

‘Let the Baron’s men come,’ I told him. ‘The Lich Road is as good as any bridge. Ten men could hold an army here. Them that wants to flank us can drown in the bog.’

Makin nodded, still hunting his breath.

‘The ones who built this road … if they’d make me a castle—’ Thunder in the east cut across my words.

‘If the Road-men built castles we’d never get in anywhere,’ Makin said. ‘Be happy they’re gone.’

We watched the brothers come in. The sunset turned the marsh pools to orange fire, and I thought of Mabberton.

‘A good day, Brother Makin,’ I said.

‘Indeed, Brother Jorg,’ he said.

So, the brothers came and set to arguing over the wrigglers. I went and sat against the loot-cart to read while the light stayed with us and the rain held off. The day left me in mind to read Plutarch. I had him all to myself, sandwiched between leather covers. Some worthy monk spent a lifetime on that book. A lifetime hunched over it, brush in hand. Here the gold, for halo, sun, and scrollwork. Here a blue like poison, bluer than a noon sky. Tiny vermilion dots to make a bed of flowers. Probably went blind over it, that monk. Probably poured his life in here, from young lad to grey-head, prettying up old Plutarch’s words.

The thunder rolled, the wrigglers wriggled and howled, and I sat reading words that were older than old before the Road-men built their roads.

‘You’re cowards! Women with your swords and axes!’ One of the crow-feasts on the gibbet had a mouth on him.

‘Not a man amongst you. All pederasts, trailing up here after that little boy.’ He curled his words up at the end like a Merssy-man.

‘There’s a fella over here got an opinion about you, Brother Jorg!’ Makin called out.

A drop of rain hit my nose. I closed the cover on Plutarch. He’d waited a while to tell me about Sparta and Lycurgus, he could wait some more and not get wet doing it. The wriggler had more to say and I let him tell it to my back. On the road you’ve got to wrap a book well to keep the rain out. Ten turns of oilcloth, ten more turns the other way, then stash it under a cloak in a saddlebag. A good saddlebag mind, none of that junk from the Thurtans, good double-stitched leather from the Horse Coast.

The lads parted to let me up close. The gibbet stank worse than the head-cart, a crude thing of fresh-cut timber. Four cages hung there. Two held dead men. Very dead men. Legs dangling through the bars, raven-pecked to the bone. Flies thick about them, like a second skin, black and buzzing. The lads had taken a few pokes at one of the wrigglers, and he didn’t look too cheerful for it. In fact he looked as if he’d pegged it. Which was a waste, as we had a whole night ahead of us, and I’d have said as much, but for the wriggler with the mouth.

‘So now the boy comes over! He’s finished looking for lewd pictures in his stolen book.’ He sat crouched up in his cage, his feet all bleeding and raw. An old man, maybe forty, all black hair and grey beard and dark eyes glittering. ‘Take the pages to wipe your dung, boy,’ he said fierce-like, grabbing the bars all of a sudden, making the cage swing. ‘It’s the only use you’ll get from it.’

‘We could set a slow fire?’ Rike said. Even Rike knew the old man just wanted us angry, so we’d finish him quick. ‘Like we did at the Turston gibbets.’

A few chuckles went up at that. Not from Makin though. He had a frown on under his dirt and soot, staring at the wriggler. I held up a hand to quiet them down.

‘It’d be a shameful waste of such a fine book, Father Gomst,’ I said.

Like Makin, I’d recognized Gomst through all that beard and hair. Without that accent though he’d have got roasted.

‘Especially an “On Lycurgus” written in high Latin, not that pidgin-Romano they teach in church.’

‘You know me?’ He asked it in a cracked voice, weepy all of a sudden.

‘Of course I do.’ I pushed both hands through my lovely locks, and set my hair back so he could see me proper in the gloom. I have the sharp dark looks of the Ancraths. ‘You’re Father Gomst, come to take me back to school.’

‘Pr-prin …’ He was blubbing now, unable to get his words out. Disgusting really. Made me feel as if I’d bitten something rotten.

‘Prince Honorous Jorg Ancrath, at your service.’ I did my court bow.

‘Wh-what became of Captain Bortha?’ Father Gomst swung gently in his cage, all confused.

‘Captain Bortha, sir!’ Makin snapped a salute and stepped up. He had blood on him from the first wriggler.

We had us a deathly silence then. Even the chirp and whir of the marsh hushed down to a whisper. The brothers looked from me, back to the old priest, and back to me, mouths hanging open. Little Rikey couldn’t have looked more surprised if you’d asked him nine times six.

The rain chose that moment to fall, all at once as if the Lord Almighty had emptied his chamber pot over us. The gloom that had been gathering set thick as treacle.

‘Prince Jorg!’ Father Gomst had to shout over the rain. ‘The night! You’ve got to run!’ He held the bars of his cage, white-knuckled, wide eyes unblinking in the downpour, staring into the darkness.

And through the night, through the rain, over the marsh where no man could walk, we saw them coming. We saw their lights. Pale lights such as the dead burn in deep pools where men aren’t meant to look. Lights that’d promise whatever a man could want, and would set you chasing them, hunting answers and finding only cold mud, deep and hungry.

I never liked Father Gomst. He’d been telling me what to do since I was six, most often with the back of his hand as the reason.

‘Run Prince Jorg! Run!’ old Gomsty howled, sickeningly self-sacrificing.

So I stood my ground.

Brother Gains wasn’t the cook because he was good at cooking. He was just bad at everything else.